Table of Contents |

The placenta is the lifeline between the mother and the child, providing the nutrients and oxygen that the fetus needs and carrying away waste through blood vessels.

During the first several weeks of development, the cells of the endometrium—referred to as decidual cells—nourish the embryo. During prenatal weeks 4–12, the developing placenta gradually takes over the role of feeding the embryo, and the decidual cells are no longer needed.

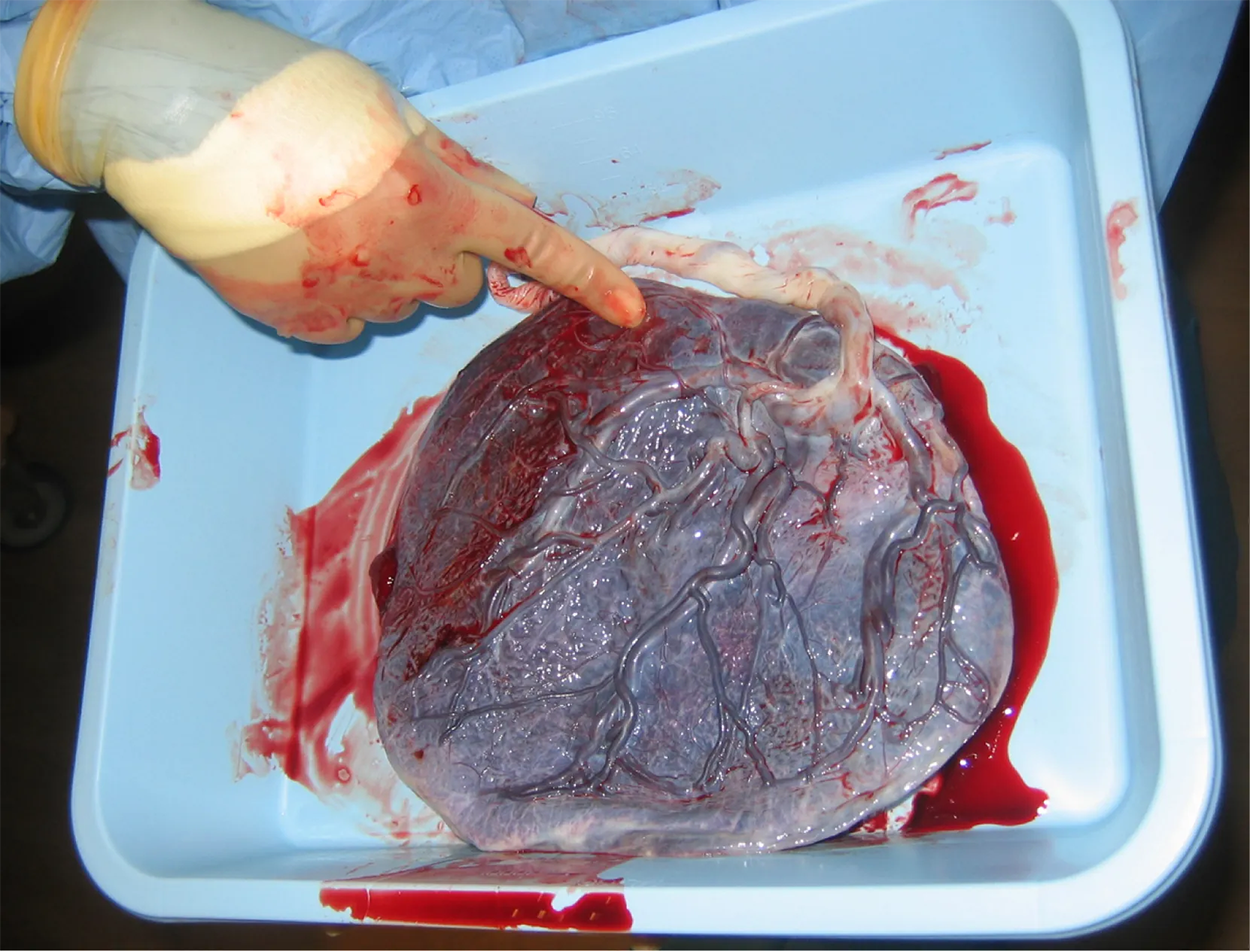

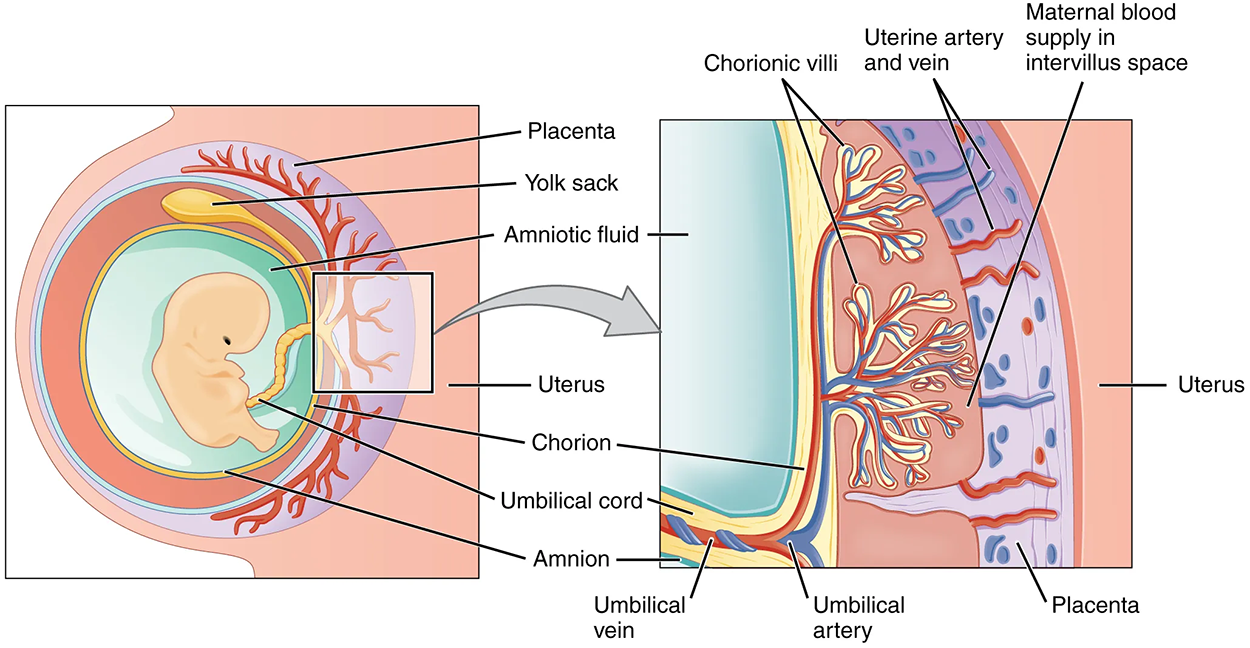

The mature placenta is composed of tissues derived from the embryo and maternal tissues of the endometrium. The placenta connects to the embryo via the umbilical cord, which carries deoxygenated blood and wastes throughout pregnancy from the fetus through two umbilical arteries; nutrients and oxygen are carried from the pregnant person to the fetus through the single umbilical vein. The umbilical cord is surrounded by the amnion, and the spaces within the cord around the blood vessels are filled with Wharton’s jelly, which is a gelatinous connective tissue.

The maternal portion of the placenta develops from the deepest layer of the endometrium, the decidua basalis. To form the embryonic portion of the placenta, the syncytiotrophoblast and the underlying cells of the trophoblast (cytotrophoblast cells) begin to proliferate along with a layer of extraembryonic mesoderm cells. These form the chorionic membrane, which envelops the entire embryo as the chorion.

The chorionic membrane forms finger-like structures called chorionic villi that burrow into the endometrium like tree roots, making up the fetal portion of the placenta. The cytotrophoblast cells perforate the chorionic villi, burrow farther into the endometrium, and remodel maternal blood vessels to augment maternal blood flow surrounding the villi. Meanwhile, fetal mesenchymal cells derived from the mesoderm fill the villi and differentiate into blood vessels, including the three umbilical blood vessels that connect the embryo to the developing placenta.

The placenta develops throughout the embryonic period and during the first several weeks of the fetal period; this process, called placentation, is complete by weeks 14–16. As a fully developed organ, the placenta provides nutrition and has excretion, respiration, and endocrine functions (see the table below).

The placenta receives blood from the fetus through the umbilical arteries. Capillaries in the chorionic villi filter fetal wastes out of the blood and return clean, oxygenated blood to the fetus through the umbilical vein. Nutrients and oxygen are transferred from maternal blood surrounding the villi through the capillaries and into the fetal bloodstream. Some substances move across the placenta by simple diffusion. Oxygen, carbon dioxide, and any other lipid-soluble substances take this route. Other substances move across by facilitated diffusion. This includes water-soluble glucose. The fetus has a high demand for amino acids and iron, and those substances are moved across the placenta by active transport.

Maternal and fetal blood do not commingle because blood cells cannot move across the placenta. This separation prevents the pregnant person's cytotoxic T cells from reaching and subsequently destroying the fetus, which bears “non-self” antigens. Further, it ensures the fetal red blood cells do not enter the pregnant person's circulation and trigger antibody development (if they carry “non-self” antigens)—at least until the final stages of pregnancy or birth.

Although blood cells are not exchanged, the chorionic villi provide ample surface area for the two-way exchange of substances between maternal and fetal blood. The rate of exchange increases throughout gestation as the villi become thinner and increasingly branched.

| Functions of the Placenta | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition and digestion | Respiration | Endocrine function |

|

|

|

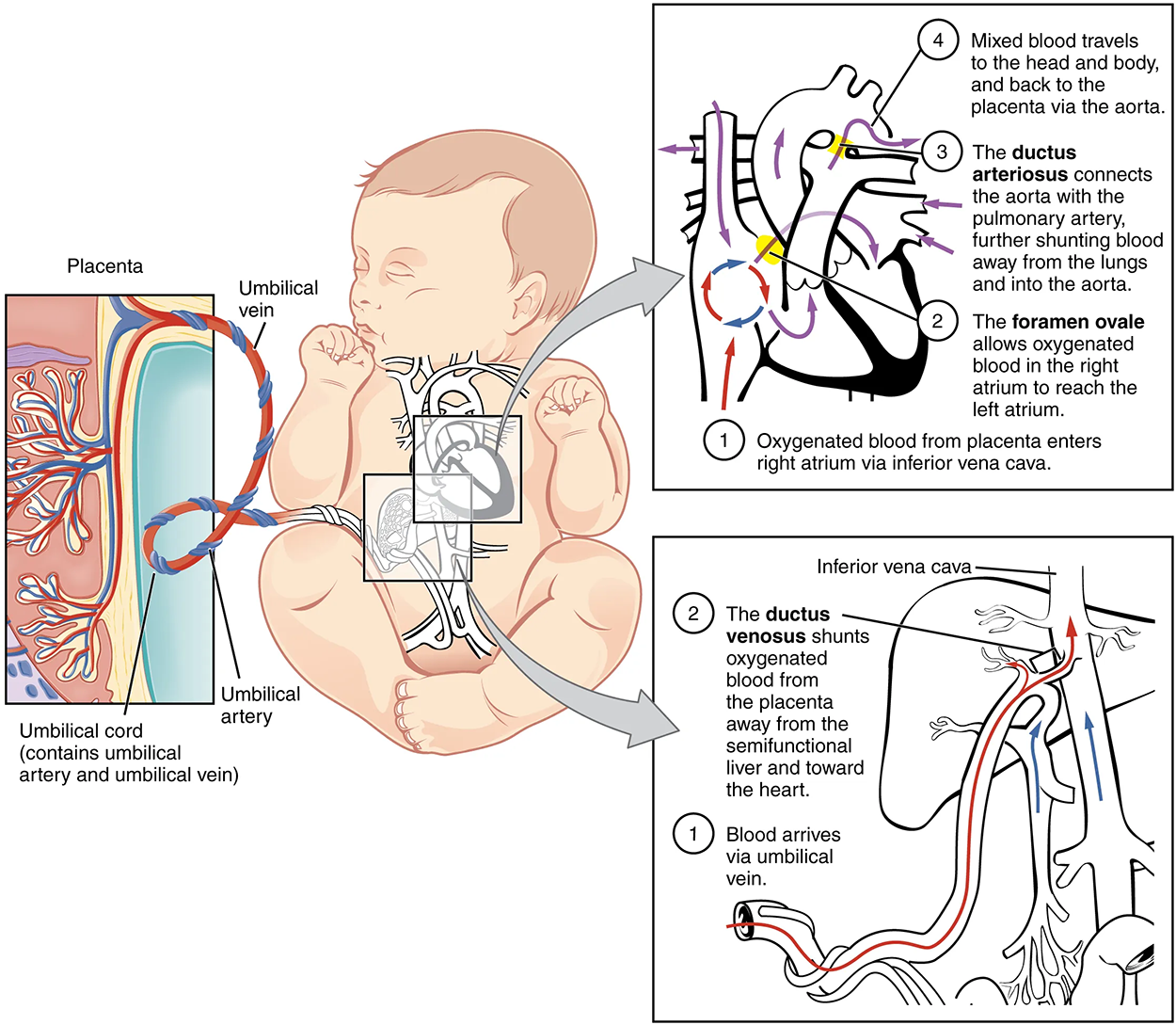

The circulatory system of a fetus is composed of temporary vessels and lungs that do not function while inside the uterus. While the fetus is within the uterus, gas exchange is not occurring like it usually would.

When the heart first forms in the embryo, it exists as two parallel tubes derived from mesoderm and lined with endothelium, which then fuse together. As the embryo develops into a fetus, the tube-shaped heart folds and further differentiates into the four chambers present in a mature heart. Unlike a mature cardiovascular system, however, the fetal cardiovascular system also includes circulatory shortcuts, or shunts. A shunt is an anatomical (or sometimes surgical) diversion that allows blood flow to bypass immature organs such as the lungs and liver until childbirth.

Therefore, during prenatal development, the fetal circulatory system is integrated with the placenta via the umbilical cord so that the fetus receives both oxygen and nutrients from the placenta. The lungs at that point are not functioning because the placenta is playing this role by delivering oxygen and removing carbon dioxide; the fetus is not actually breathing.

The placenta provides the fetus with necessary oxygen and nutrients via the umbilical vein. (Remember that veins carry blood toward the heart. In this case, the blood flowing to the fetal heart is oxygenated because it comes from the placenta. The respiratory system is immature and cannot yet oxygenate blood on its own.) From the umbilical vein, the oxygenated blood flows toward the inferior vena cava, all but bypassing the immature liver, via the ductus venosus shunt. The liver receives just a trickle of blood, which is all that it needs in its immature, semifunctional state. Blood flows from the inferior vena cava to the right atrium, mixing with fetal venous blood along the way.

Although the fetal liver is semifunctional, the fetal lungs are nonfunctional. The fetal circulation therefore bypasses the lungs by shifting some of the blood through the foramen ovale. As you previously learned, the foramen ovale is the opening in the fetal interatrial septum that directly connects and allows blood to pass from the right and left atria, and it avoids the pulmonary trunk altogether. Most of the rest of the blood is pumped to the right ventricle, and from there, into the pulmonary trunk, which splits into pulmonary arteries. However, a shunt within the pulmonary artery, the ductus arteriosus, diverts a portion of this blood into the aorta. This ensures that only a small volume of oxygenated blood passes through the immature pulmonary circuit, which has only minor metabolic requirements.

After childbirth, the umbilical cord is severed, and the newborn’s circulatory system must be reconfigured. Once the baby is born, the circulatory system becomes independent, and the lungs will begin gas exchange when the first breath is taken. While the fetus is within the mother, the circulatory system depends on the mother's circulation to undergo gas exchange vs. breathing air.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.