Table of Contents |

Phototrophic bacteria are a diverse group that all use light energy to build carbon-based compounds such as sugars. They are found in multiple taxa. Some are gram-positive and some are gram-negative. Both Proteobacteria and nonproteobacteria include some phototrophic bacteria.

Phototrophic bacteria use photosynthesis to produce ATP and this ATP is used to power cellular activities and reactions. Some produce oxygen in the process and this is called oxygenic photosynthesis. The majority of bacteria do not produce oxygen and therefore perform anoxygenic photosynthesis.

One large group of phototrophic bacteria includes the purple or green bacteria that perform photosynthesis with the help of bacteriochlorophylls. These chemicals are green, purple, or blue pigments similar to chlorophyll in plants. Other bacteria have a varying amount of red or orange pigments called carotenoids. Their color varies from orange to red to purple to green. Because the color represents light reflected, this means that bacteria that appear different colors when exposed to the same wavelength of visible light absorb light of different wavelengths. Traditionally, these bacteria are classified into sulfur and nonsulfur bacteria; they are further differentiated by color. The sulfur bacteria perform anoxygenic photosynthesis, using sulfites (SO₃²⁻) as electron donors and releasing free elemental sulfur. Nonsulfur bacteria use organic substrates, such as succinate and malate, as donors of electrons.

The photo below shows patches of green and purple where green and purple bacteria, respectively, are growing in a glass container.

The purple sulfur bacteria oxidize hydrogen sulfide into elemental sulfur and sulfuric acid. They get their purple color from two types of pigments: bacteriochlorophylls and carotenoids.

EXAMPLE

Genus Chromatium is a particularly well-known example of these bacteria as it has been used for studies of bacterial photosynthesis. This genus is classified within the Gammaproteobacteria.The green sulfur bacteria use sulfide for oxidation and produce large amounts of green bacteriochlorophyll.

EXAMPLE

The genus Chlorobium is a green sulfur bacterium that is implicated in climate change because it produces methane, a greenhouse gas.These bacteria use at least four types of chlorophyll for photosynthesis. The most prevalent of these, bacteriochlorophyll, is stored in special vesicle-like organelles called chlorosomes.

Purple nonsulfur bacteria are similar to purple sulfur bacteria except that they use hydrogen rather than hydrogen sulfide for oxidation.

EXAMPLE

The genus Rhodospirillum is an example of this group and may be valuable for biotechnology purposes because of their potential ability to produce biological plastic and hydrogen fuel.The green nonsulfur bacteria are similar to green sulfur bacteria, but use substrates other than sulfides for oxidation.

EXAMPLE

Chloroflexus is a green nonsulfur bacterium. It often has an orange color when it grows in the dark, but becomes green when it grows in sunlight. It stores bacteriochlorophyll in chlorosomes, similar to Chlorobium, and performs anoxygenic photosynthesis using organic sulfites (low concentrations) or molecular hydrogen as electron donors. It can survive in the dark if oxygen is available.The cyanobacteria are a large, diverse phylum of phototrophic bacteria. Species of this group perform oxygenic photosynthesis, producing gaseous oxygen. These bacteria are believed to have played a crucial role in changing the planet’s anoxic atmosphere to the oxygen-rich atmosphere present today. The primary photosynthetic pigment is chlorophyll, although they also use two secondary photosynthetic pigments: phycocyanin and cyanophycin. These pigments are located in special organelles called phycobilisomes and in folds on the cellular membrane called thylakoids.

Cyanobacteria sometimes produce harmful blooms. They form dense mats on bodies of water and produce large quantities of toxins.

The table below summarizes characteristics of phototrophic bacteria.

| Phototrophic Bacteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Class | Example Genus or Species |

Common Name |

Oxygenic or Anoxygenic | Sulfur Deposition |

| Cyanobacteria | Cyanophyceae | Microcystis aeruginosa |

Blue-green bacteria |

Oxygenic | None |

| Chlorobi | Chlorobia | Chlorobium |

Green sulfur bacteria |

Anoxygenic | Outside the cell |

| Chloroflexi (Division) | Chloroflexi | Chloroflexus |

Green nonsulfur bacteria |

Anoxygenic | None |

| Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Rhodospinillum |

Purple nonsulfur bacteria |

Anoxygenic | None |

| Betaproteobacteria | Rhodocyclus |

Purple nonsulfur bacteria |

Anoxygenic | None | |

| Gammaproteobacteria | Chromatium |

Purple sulfur bacteria |

Anoxygenic | Inside the cell | |

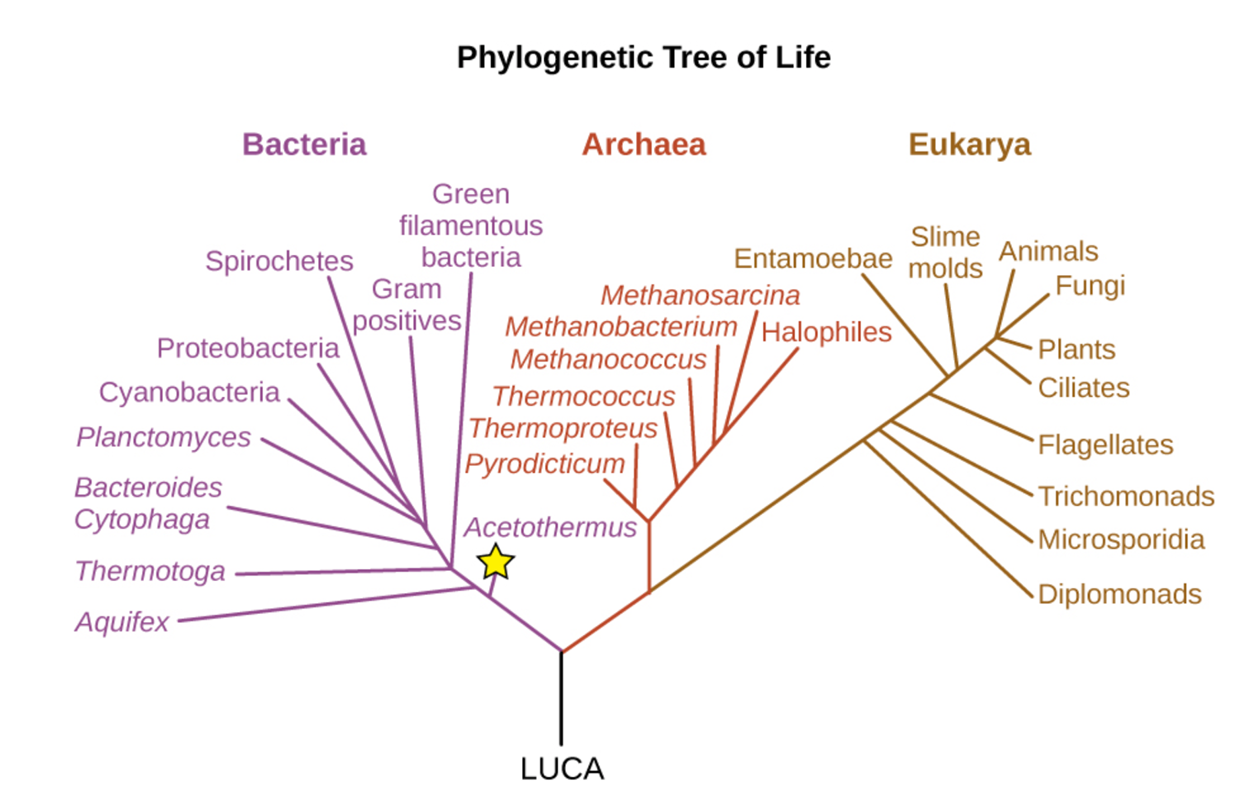

The deeply branching bacteria are the first branches of a phylogenetic tree near the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) at the root of the tree.

EXAMPLE

On the image below, a class of deeply branching bacteria is Acetothermus. Other deeply branching bacteria include classes Aquifex and Thermotoga and Dinococcus radiodurans.

The deeply branching bacteria may provide clues regarding the structure and function of ancient and now extinct forms of life. We can hypothesize that ancient bacteria, like the deeply branching bacteria that still exist, were thermophiles or hyperthermophiles, meaning that they thrived at high or very high temperatures, respectively.

At present, the deepest branching bacterium and therefore the closest relative of the LUCA known is Acetothermus pauvicorans, which is a gram-negative bacterium that is a thermophile.

The class Aquificae includes deeply branching bacteria that are adapted to the harshest conditions on Earth, resembling the conditions thought to dominate Earth when life first appeared. Bacteria from the genus Aquifex are hyperthermophiles and live in hot springs at a temperature above 90 °C.

EXAMPLE

One Aquifex species, A. pyrophilus, thrives in deep water that can reach 138 °C. Bacteria in this class can reduce oxygen and can reduce nitrogen when oxygen is not present. They show a remarkable resistance to ultraviolet light and ionizing radiation.These observations support the hypothesis that the ancient ancestors of deeply branching bacteria began evolving more than 3 billion years ago. At this time, the Earth was hot and lacked an atmosphere. With no atmosphere, the bacteria were exposed to higher amounts of nonionizing and ionizing radiation than reaches the Earth at present.

The class Thermotogae is represented by gram-negative bacteria whose cells are wrapped in a sheath-like outer membrane called a toga. The class includes hyperthermophiles, but also includes some mesophiles (i.e., organisms that prefer moderate temperatures). These organisms are anaerobic, meaning that they live in oxygen-free environments. The thin layer of peptidoglycan in their cell wall has an unusual structure containing diaminopimelic acid and D-lysine. These organisms can use a variety of organic substrates and produce molecular hydrogen, which is useful in industry.

EXAMPLE

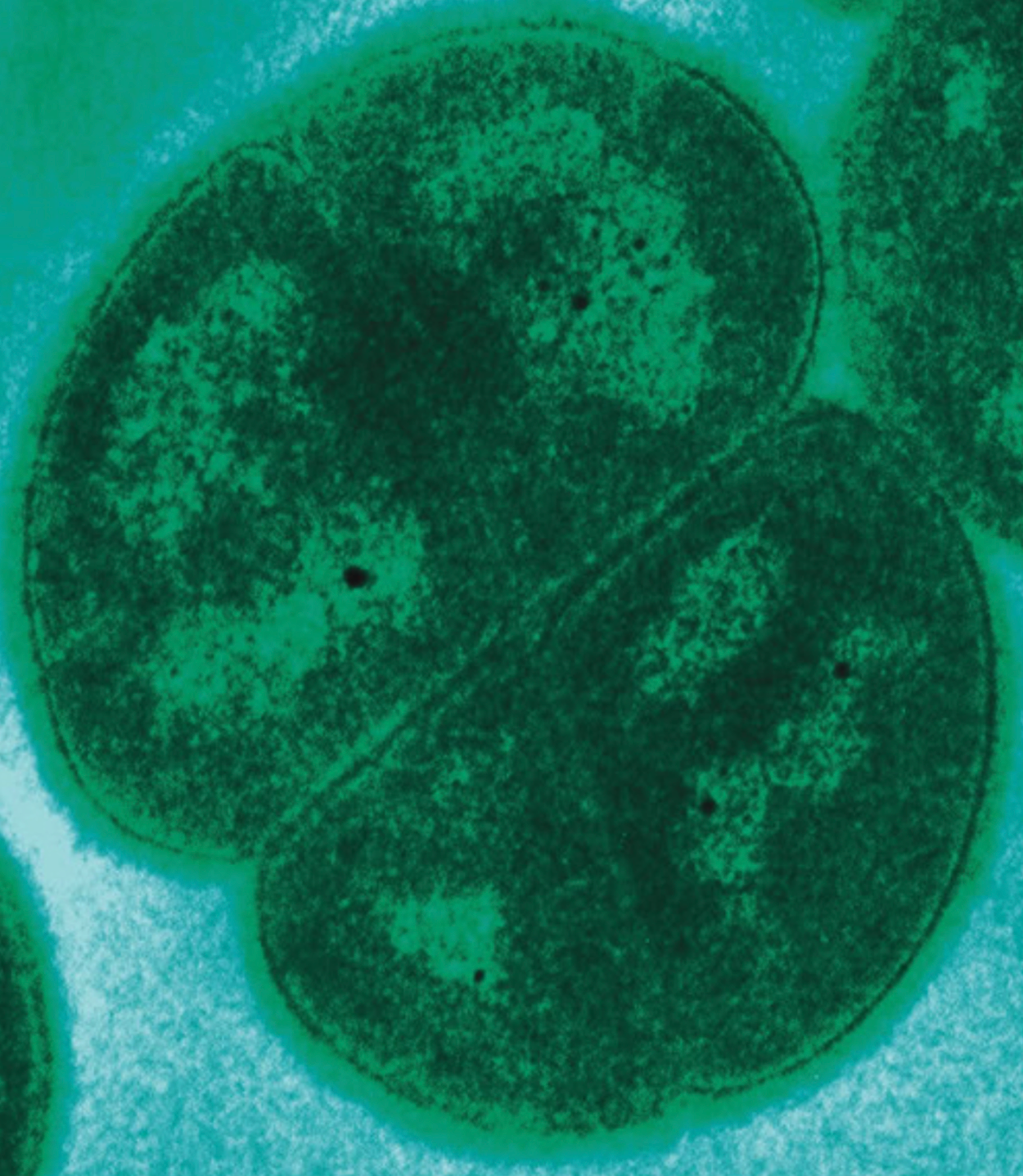

The deeply branching bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans is considered a polyextremophile because it can survive under a variety of extreme conditions (extreme heat, drought, vacuum, acidity, and radiation). It can withstand doses of ionizing radiation that kill all other known bacteria and this is believed to be possible due to unique mechanisms of DNA repair.The micrograph below shows D. radiodurans as a clump of four spheres that are flattened where they meet.

Although the rest of this lesson and other lessons have focused on different taxa within domain Bacteria, it is important to recognize domain Archaea as another domain rather than a subgroup of bacteria.

Domain Archaea is as diverse as domain Bacteria and its representatives can be found in any habitat. Some thrive in extreme conditions such as very high temperatures or very salty environments, but others are mesophiles that thrive at moderate temperatures (such as on or inside the human body).

At present, archaea do not appear to be associated with human disease. However, as more is learned about which species are present on and within humans, it may be possible to draw more conclusions about their roles in human health and disease.

The taxonomy of domain Archaea is in a state of flux as new analyses are carried out and as recommendations for formal naming are updated. Therefore, it is always important to check recommendations for nomenclature. In this lesson, we will use five phyla of Archaea: Crenarchaeota, Euryarchaeota, Korarchaeota, Nanoarcheota, and Thaumarchaeota.

Crenarchaeota is a highly diverse group of aquatic organisms. They are thought to be the most abundant microorganisms in the oceans.

EXAMPLE

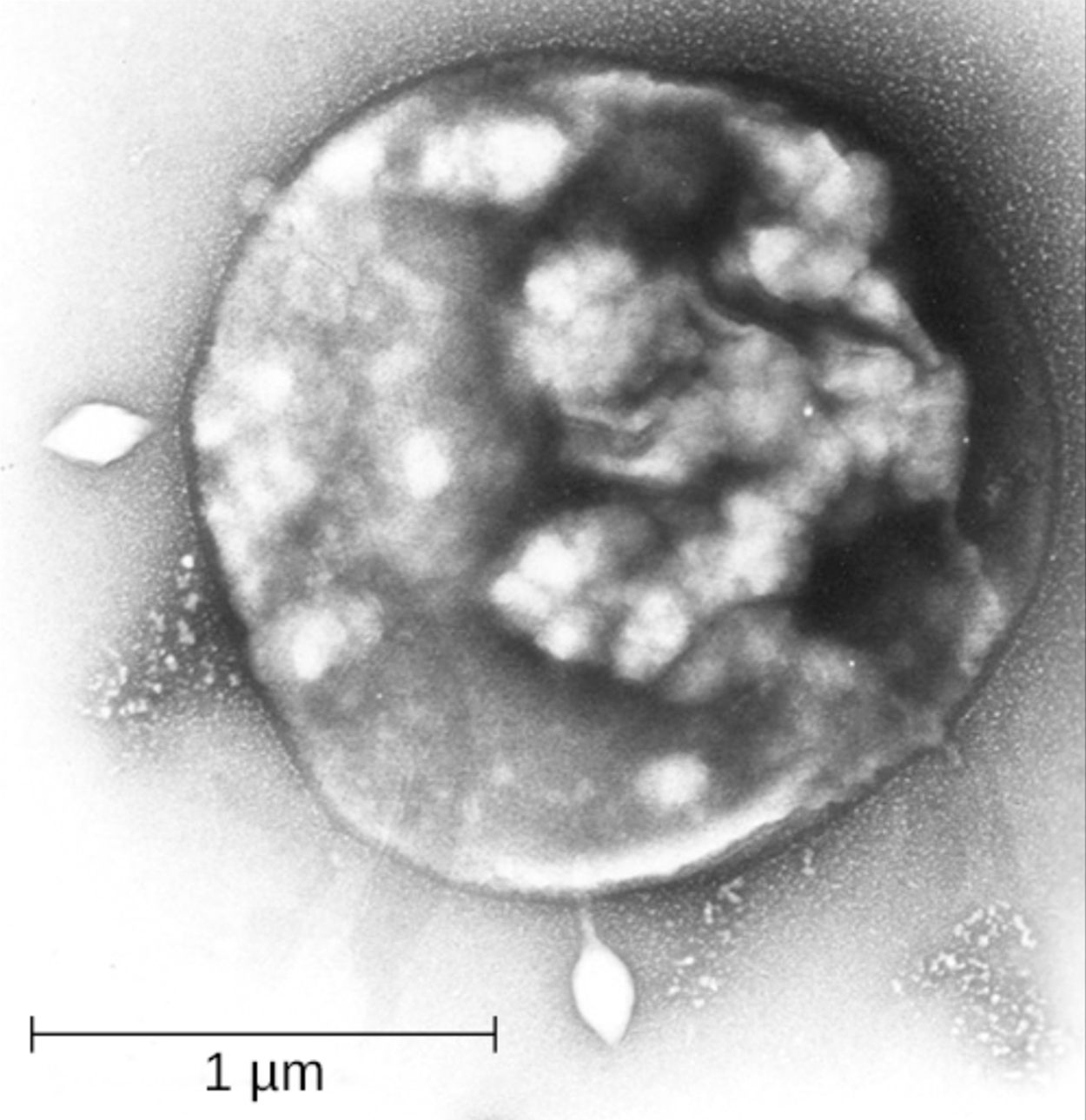

Sulfolobus, which is shown in the micrograph below, is an example of this class. Another example is Thermoproteus, which has a monolipid membrane.

Phylum Euryarchaeota includes several classes that contain methanogens (Methanobacteria, Methanococci, and Methanomicrobia) and a class of archaeans that require high salt concentrations (Halobacteria). Methanogens can produce methane and can thrive in temperatures ranging from freezing to boiling. In addition to their unusual habitats, Halobacteria perform photosynthesis using the protein bacteriorhodopsin and therefore have a purple color. The photo below shows rectangular pools of water containing Halobacteria, showing their unique color.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT openstax.org/details/books/microbiology. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Bang, C., & Schmitz, R. A. (2015). Archaea associated with human surfaces: not to be underestimated. FEMS microbiology reviews, 39(5), 631–648. doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuv010

de Cena, J. A., Silvestre-Barbosa, Y., Belmok, A., Stefani, C. M., Kyaw, C. M., & Damé-Teixeira, N. (2022). Meta-analyses on the Periodontal Archaeome. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 1373, 69–93. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96881-6_4

Hoffmann, C., Dollive, S., Grunberg, S., Chen, J., Li, H., Wu, G. D., Lewis, J. D., & Bushman, F. D. (2013). Archaea and fungi of the human gut microbiome: correlations with diet and bacterial residents. PloS one, 8(6), e66019. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066019

Lurie-Weinberger, M. N., & Gophna, U. (2015). Archaea in and on the Human Body: Health Implications and Future Directions. PLoS pathogens, 11(6), e1004833. doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004833

Oren, A., & Garrity, G. M. (2021). Valid publication of the names of forty-two phyla of prokaryotes. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology, 71(10), 10.1099/ijsem.0.005056. doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.005056

Parker, N., Schneegurt, M., Thi Tu, A.-H., Lister, P., & Forster, B. (2016). Microbiology. OpenStax. Access for free at openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction