Table of Contents |

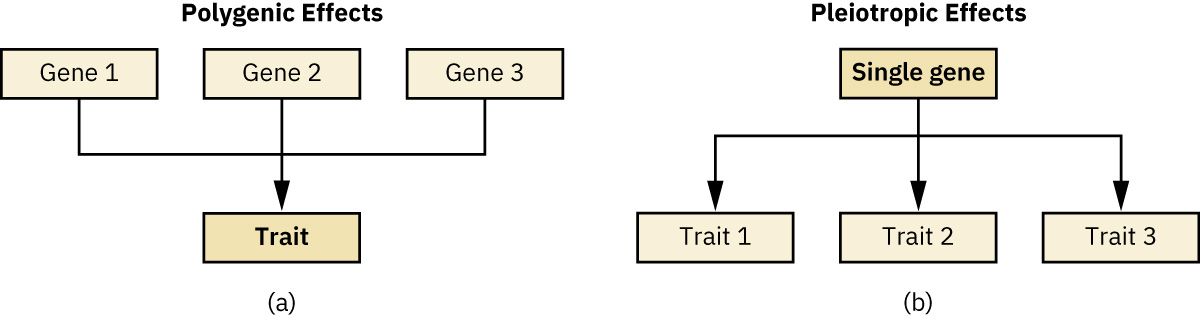

Mendel’s studies on pea plants implied that the sum of an individual’s phenotype was controlled by genes (or as he called them, unit factors), such that every characteristic was distinctly and completely controlled by a single gene. In fact, single observable characteristics are almost always under the influence of multiple genes (each with two or more alleles) acting in unison. These traits are referred to as polygenic traits. For example, at least eight genes contribute to eye color in humans. Most of our traits that are expressed are determined by many genes, with very few traits determined by one single gene.

In some cases, several genes can contribute to aspects of a common phenotype without their gene products ever directly interacting. In the case of organ development, for instance, genes may be expressed sequentially (in a specific order), with each gene adding to the complexity and specificity of the organ. Genes may function in complementary or synergistic fashions, such that two or more genes expressed simultaneously affect a phenotype. An apparent example of this occurs with human skin color, which appears to involve the action of at least three (and probably more) genes. Cases in which inheritance for a characteristic like skin color or human height depend on the combined effects of numerous genes are called polygenic inheritance.

Together, the effects of all the individual genes add up to create the observed phenotype. Scientists are beginning to identify which combinations of genes are associated with a range of complex traits and diseases such as cognitive ability, major depressive disorder, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease (Tam et al., 2019). Not all the phenotypic variation observed is accounted for by genes, however, and environmental factors also contribute to the expression of a trait.

Polygenic traits can show continuous variation within a population. Height is a good example of a polygenic trait because, within a given population, we could have a wide range of continuous differences of that trait. Height is also a multifactorial trait, meaning that it is determined by multiple factors such as the combination of a person’s genes and environment.

Genes may also oppose each other, with one gene suppressing the expression of another. In epistasis, the interaction between genes is antagonistic, such that one gene masks or interferes with the expression of another. “Epistasis” is a word composed of Greek roots meaning “standing upon.” The alleles that are being masked or silenced are said to be hypostatic to the epistatic alleles that are doing the masking. Often, the biochemical basis of epistasis is a gene pathway in which expression of one gene is dependent on the function of a gene that precedes or follows it in the pathway. In humans, epistasis is common in pigmentation genetics.

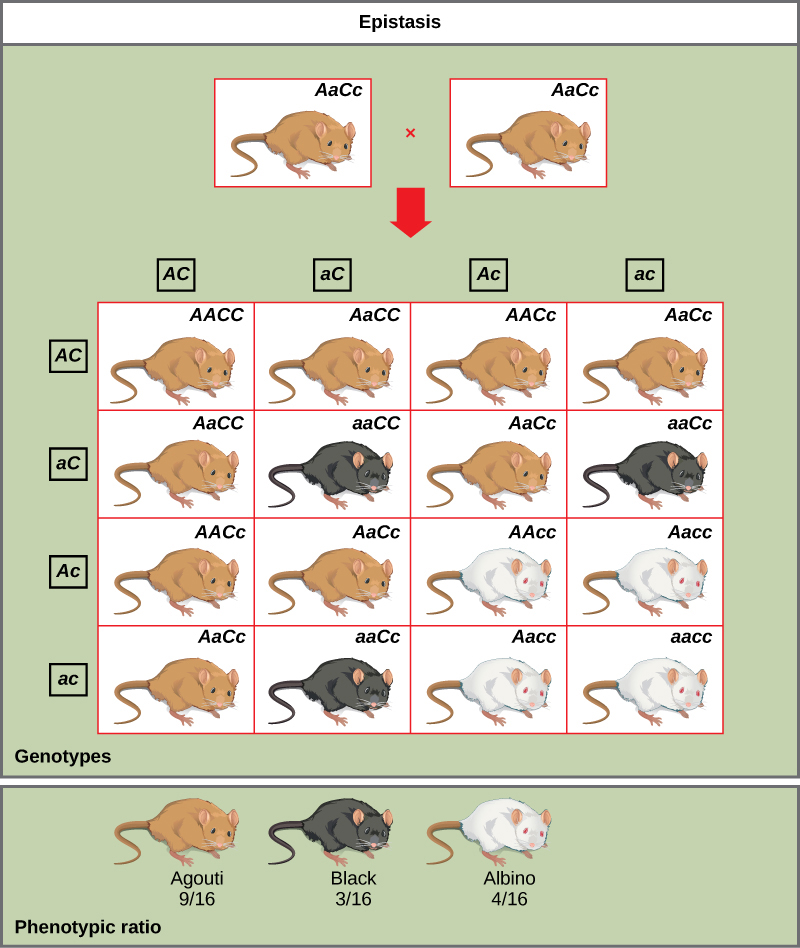

The example below describes the role of epistasis in pigmentation of mice. The wild-type coat color, agouti (AA), is dominant to solid-colored fur (aa). However, a separate gene C, when present as the recessive homozygote (cc), negates any expression of pigment from the A gene and results in an albino mouse. Therefore, the genotypes AAcc, Aacc, and aacc all produce the same albino phenotype. A cross between heterozygotes for both genes (AaCc x AaCc) would generate offspring with a phenotypic ratio of 9 agouti:3 black:4 albino. In this case, the C gene is epistatic to the A gene.

Epistasis can also occur when a dominant allele masks expression at a separate gene. Fruit color in summer squash is expressed in this way. Homozygous recessive expression of the W gene (ww) coupled with homozygous dominant or heterozygous expression of the Y gene (YY or Yy) generates yellow fruit, and the wwyy genotype produces green fruit. However, if a dominant copy of the W gene is present in the homozygous or heterozygous form, the summer squash will produce white fruit regardless of its Y alleles. A cross between white heterozygotes for both genes (WwYy ×WwYy) would produce offspring with a phenotypic ratio of 12 white:3 yellow:1 green.

Finally, epistasis can be reciprocal such that either gene, when present in the dominant (or recessive) form, expresses the same phenotype. In the shepherd’s purse plant (Capsella bursa-pastoris), the characteristic of seed shape is controlled by two genes in a dominant epistatic relationship. When the genes A and B are both homozygous recessive (aabb), the seeds are ovoid (egg shaped). If the dominant allele for either of these genes is present, the result is triangular seeds. That is, every possible genotype other than aabb results in triangular seeds, and a cross between heterozygotes for both genes (AaBb x AaBb) would yield offspring with a phenotypic ratio of 15 triangular:1 ovoid.

As you work through genetics problems, keep in mind that any single characteristic that results in a phenotypic ratio that totals 16 is typical of a two-gene interaction. Recall the phenotypic inheritance pattern for Mendel’s dihybrid cross, which considered two noninteracting genes—9:3:3:1. Similarly, we would expect interacting gene pairs to also exhibit ratios expressed as 16 parts. Note that we are assuming the interacting genes are not linked; they are still assorting independently into gametes.

Pleiotropy is the expression of one gene that affects multiple traits. An example of this is the gene that causes sickle-cell anemia in humans. This gene produces various effects throughout the body and can affect the way the blood carries oxygen, other internal organs, et cetera.

Another example is PKU (phenylketonuria), a single-gene recessive disorder. This mutation results in the ineffective metabolism of phenylalanine (found in milk and other foods), bringing about a variety of issues if untreated, such as cognitive disability, eczema, and delayed growth (Elhawary et al., 2022; Targum & Lang, 2010).

Another type of pleiotropic effect occurs when genes referred to as generalist genes affect different but related phenotypes. For example, the same genetic variants are shared across verbal and nonverbal cognitive abilities (Bearden & Glahn, 2017), and shared genetic variants are indicated across several psychiatric disorders (Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2019).

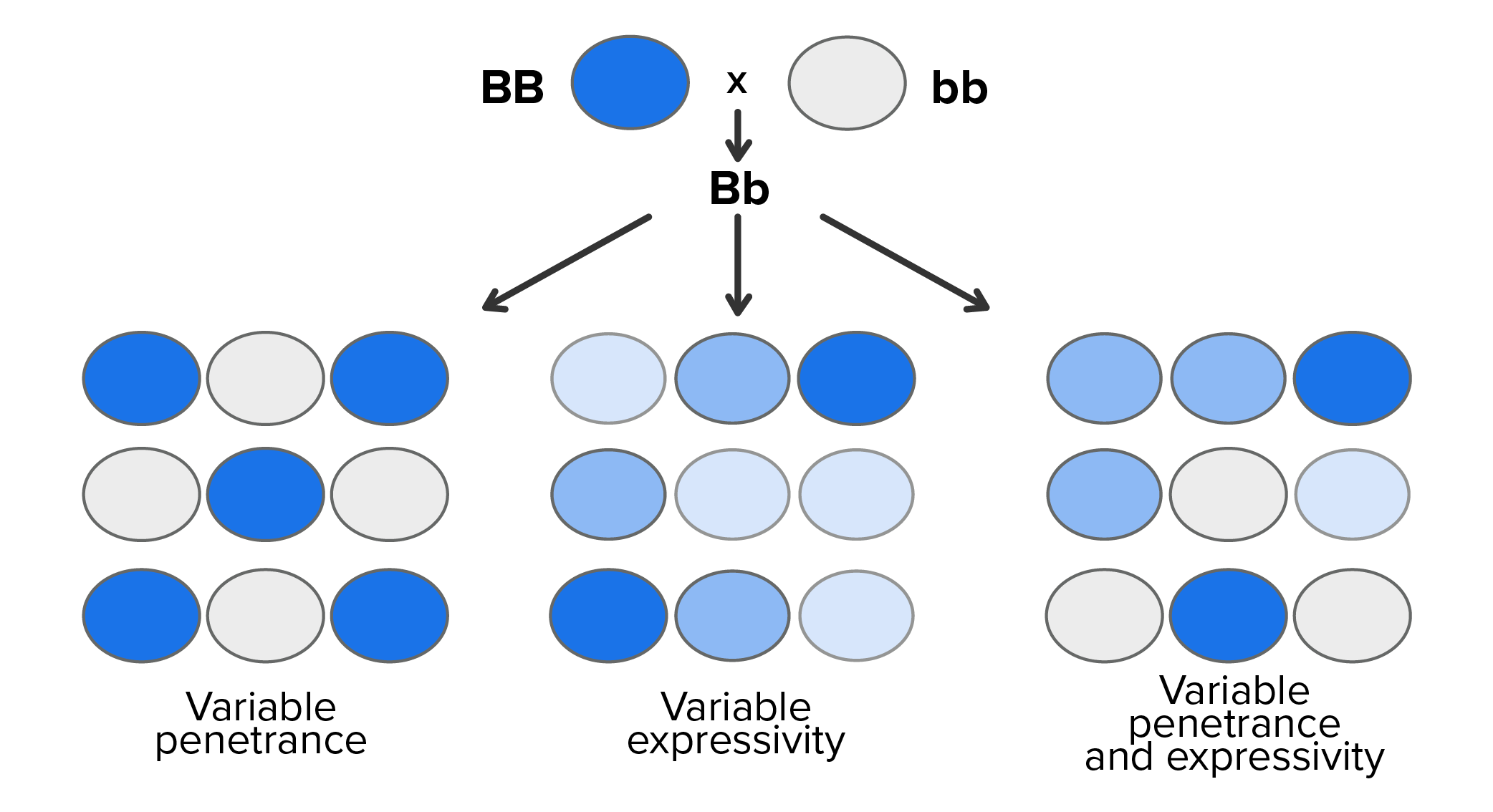

Penetrance is the varying degree to which someone expresses a trait that's associated with an allele. Incomplete penetrance means that some people who inherit a disease allele will not manifest the disease in their phenotype. For example, mutations in the BRCA1 gene cause familial breast cancer, and 80% of people who inherit one of these mutant alleles will contract breast cancer at some point during their lifetime. That means that the penetrance of these alleles is 80%; just because you have the allele doesn't guarantee the phenotypic outcome.

Cystic fibrosis is an example of a trait that would be completely penetrant. This means that 100% of people who are homozygous recessive will have cystic fibrosis.

Polydactyly would be an example of a trait that would be incompletely penetrant. Polydactyly relates to the number of digits that a person has. Some people who carry the genes for polydactyly might have the normal 10 fingers, while some people who have that trait might have more than 10 fingers. There are varying degrees to which someone expresses this trait.

By contrast, expressivity refers to variation in how a trait is expressed within individuals who have an allele with complete penetrance. Although all individuals with that genotype will express the trait to some degree, it can be expressed to varying degrees. Common causes of variable expressivity include variable loci at other parts of the genome or environmental factors that influence gene expression.

Marfan syndrome is an example of a disorder with variable expressivity. Marfan syndrome is a disorder of connective tissue caused by a variant of the FBN1 gene. This disorder causes some people to be just abnormally tall with long limbs and digits, and in other individuals it can be life-threatening, as it affects connective tissues such as heart valves.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) OPENSTAX “BIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/BIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION (2) OPENSTAX “LIFESPAN DEVELOPMENT”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/LIFESPAN-DEVELOPMENT/PAGES/1-WHAT-DOES-PSYCHOLOGY-SAY. (3) OPENSTAX “CONCEPTS OF BIOLOGY”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/CONCEPTS-BIOLOGY/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSING (1, 2, & 3): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.