Table of Contents |

Decision making, especially ethical decision making, is crucial to an organization. Decision making allows COOs and other operational managers and staff to ensure the organization runs smoothly. Operational decisions are the choices made by an organization to ensure effective running of its internal processes. This is different from strategic decisions, which are focused on long-term vision and overall organization direction. Operational decisions are those made daily to meet the overall strategic vision. The categories of decisions COOs and operations managers make include planning decisions, implementation decisions, monitoring and controlling decisions, and communication decisions, such as what decisions need to be communicated, and how they will be communicated.

Remember that Maria is COO for Gordon’s Bicycle Company. Among the decisions she will make regularly are:

While some of these decisions may not need to be made on a daily basis, she might also have to make on-the-spot decisions like:

- How to allocate resources, such as labor and materials, for each process

- Choosing suppliers to supply the raw materials

- Which software to implement to gain efficiencies

- Hiring and workforce scheduling and planning decisions

- Where and how to implement cost control measures

- Decisions related to quality control and quality standards

While mainly focused on decisions with short-term repercussions, Maria cannot lose sight of long-term considerations, both in terms of strategy and in terms of corporate responsibility and ethics.

- How to handle an irate customer

- How to troubleshoot issues, such as delayed orders, staff shortages, or equipment issues

- Prioritizing customer orders

- How to examine products and services for quality

- Ensuring workload is balanced to achieve optimal efficiency depending on organizational needs

For each of these, Maria needs to make a decision and also be prepared to defend it if questioned later. Is her decision ethical? Is it in support of Gordon’s long-term visions for the company? Is it fair to workers and customers? Is it supported by data? Will it present the company in the best light if the decision were made public?

- What is the impact the business has on the environment and surrounding community?

- Are workers being treated fairly? Are they being nurtured and mentored to further their careers?

- Are opportunities for employment and growth being offered fairly in terms of diverse backgrounds?

Psychologists and organizational behaviorists divide decisions into two types; these categories are about how the decisions themselves are made, rather than what the decisions are about.

A programmed decision is one that is repeated over time, and for which an existing set of rules to make the decision is in place. For example, the processes (or “programs”) to determine how to order new raw materials was covered in earlier tutorials. Programmed decisions have enough historic context for decision makers to draw on past experience to make quick, informed decisions. Decisions that may be described as “intuitive” often describe programmed decisions that draw on experience and the ability of the subconscious mind to process data and inform decisions. In terms of ethics, the challenge of a programmed decision is the self-awareness and courage to change a practice if one realizes an ethical dimension has not been considered.

EXAMPLE

Demand forecasting can involve a lot of different data such as recent sales, the rise or drop in the competition, the economy, and current events. An experienced operations manager might decide to raise or lower the forecast as a programmed decision that considers all of this data in the context of past experience. A further consideration that might change this process is the schedule of workers and their work-life balance, if ambitious production goals are leading to burnout and high turnover.A non-programmed decision is new or unique, usually a decision that is not made often or is at least new to the decision maker. These types of decisions take more time to make since there isn’t an existing set of “rules” to make the decision. Because they are new, it might be clearer to the decision maker what the ethical dimensions are, but they are less likely to see the impact of their decisions on outcomes.

EXAMPLE

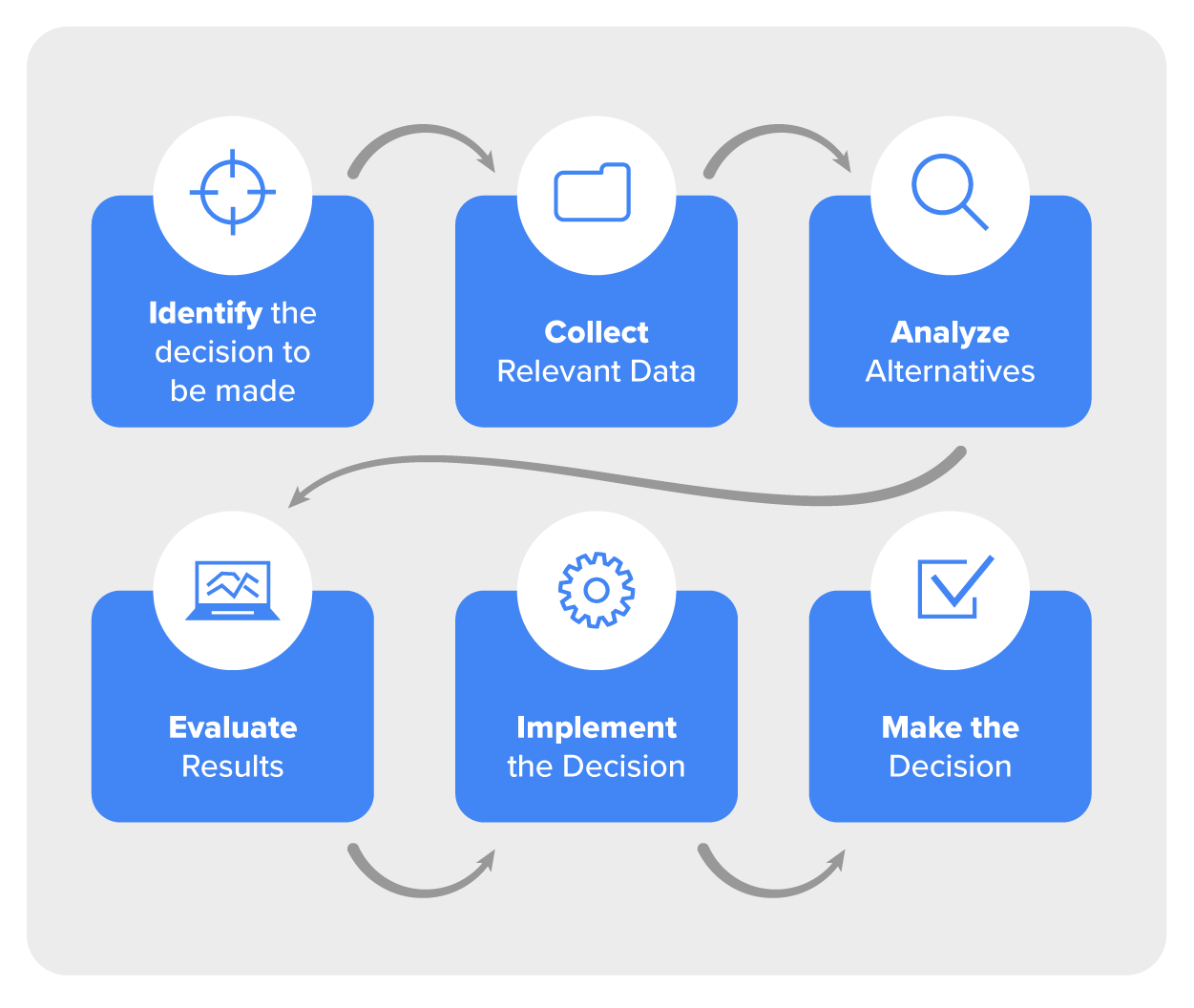

The same operations manager from the previous example would struggle to make a demand forecast in light of extraordinary conditions, such as a local weather event that has disrupted production and transportation at both sides of the supply chain. They do not know how these will affect demand or the long-term solvency of the company but decide that keeping workers and their families on the payroll is an ethical necessity.The decision-making process includes six main steps.

EXAMPLE

A software company decides when to have downtime so they can upgrade the servers. After weighing different possibilities, they decide on a weekend evening when few people use the software, and which will not require staff to work in the middle of the night. After the implementation, they discover a higher volume of calls than usual. The support representatives remind them that while few people use the software in the evening, many people do wait for a weekend to resolve technical issues. The operations manager now knows (a) to consider the factor of customer support in their decisions, and (b) to involve customer support in the decision-making process.

Another consideration in decision-making is ensuring laws and expectations of ethics are followed. There are a few ways to look at making ethical decisions, which we’ll address next.

Operations managers make many decisions based on data to meet company goals. Throughout this class you have learned various ways data can be collected, analyzed, and used to inform good decisions, as well as the core principles of efficiency, safety, quality, and customer-centeredness that guide them.

But that doesn’t mean managers always have a clear path forward. Perhaps the “best” decision in terms of efficiency and cost impacts people, such as laying off many people, or the data itself is incomplete and unclear. Perhaps one decision presents greater opportunity but greater risks. Perhaps a manager faces conflicting principles, such as saving costs by lowering quality. In many situations, there are no simple right or wrong answers.

In these situations, a manager can ask themselves questions to help find the best answer:

EXAMPLE

A factory is struggling to keep up levels of production to meet demand. An operations manager discovers that some of the machinery is overheating. While there is no evidence that continuing the high-level of production will lead to breakdowns or injuries, an ethical manager would see these as possibilities and act accordingly.The feelings test is simply asking oneself, “How does this make me feel?” This enables a decision maker to examine their comfort level with a particular decision. Many people find that after reaching a decision on an issue, they still experience discomfort that may manifest itself in a loss of sleep or appetite. Those feelings of conscience can serve as a future guide in resolving ethical dilemmas.

Maria and her team are under a tight deadline to produce 50 bikes to send to a new distributor. It appears they will not make the deadline, so Maria considers shortcuts like eliminating some of the test drives of the bikes and skipping some safety checks. This would allow them to meet the deadline. But Maria reflects, “How do I feel about cutting corners?” and “How do I feel about this being a poor example to my staff?” The truth is that skipping safety checks might result in riders being injured. Given this, she decides she would rather miss the deadline that set a precedent of unethical behavior.

This test is helpful in spotting and resolving potential conflicts of interest. The decision maker considers the repercussions of the decision if an objective report appeared on the front page of a newspaper, or if it were to “go viral” on a social media platform such as Twitter or Facebook. If it’s easy to predict a negative public response, it may be necessary to reconsider the decision.

Another consideration Maria has in meeting their ambitious production goal is the public response if it is discovered that carelessness on the part of the company led to unsafe bicycles being sold. Such a story could lead to vendors ending contracts, a slump in sales, and damage to their reputation that would be hard to recover from. She further considers that the extra hours piled on staff would also raise questions about safety for both workers and riders that would damage their reputation as an ethical employer. This helps her finalize the decision to miss the production goal, with a firm ethical defense for doing so.

Making decisions is a key skill of the operational leader. Ensuring decisions are made ethically and with the data available can help an organization meet its goals.

Source: This tutorial has been adapted from OPENSTAX “Principles of Management”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://openstax.org/books/principles-management/pages/1-introduction. License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.