Table of Contents |

The central and largest organelle of the cell is the nucleus. The nucleus (cell) is a membranous organelle that is generally considered the control center of the cell because it stores the cell’s DNA: genetic instructions for manufacturing proteins.

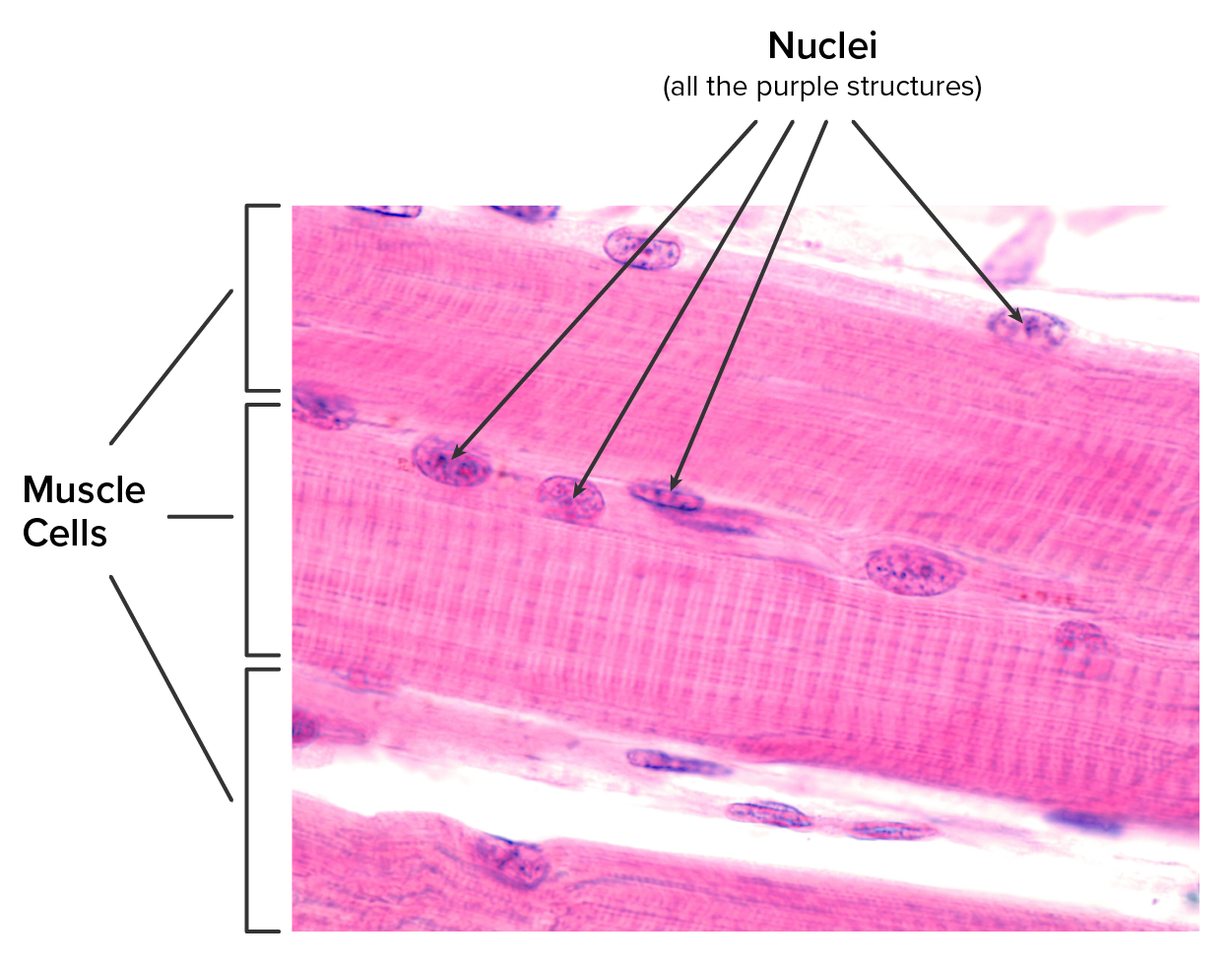

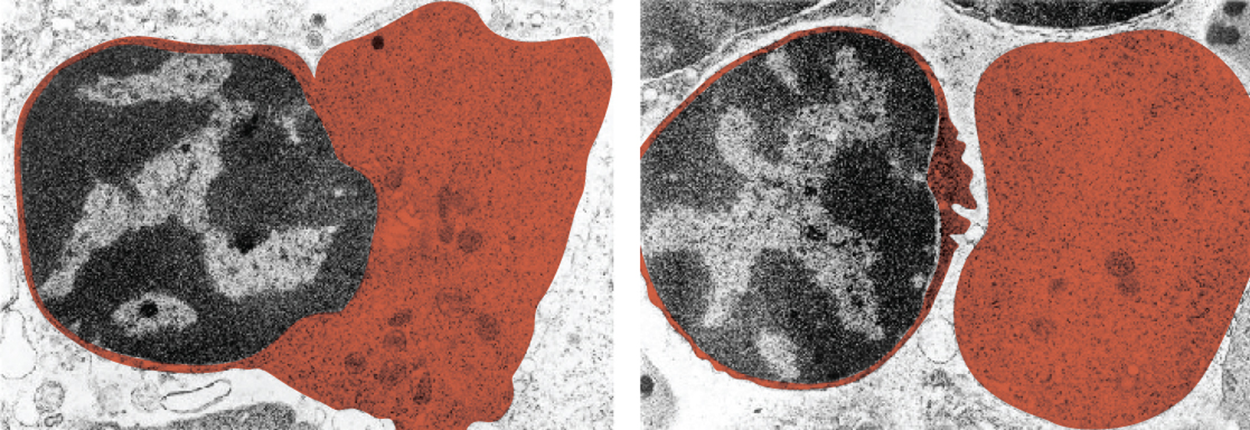

Interestingly, some cells in the body, such as muscle cells, contain more than one nucleus, which is known as multinucleated. Other cells, such as mammalian red blood cells (RBCs), do not contain nuclei at all. RBCs eject their nuclei as they mature, making space for the large numbers of proteins that carry oxygen throughout the body. Without nuclei, the life span of RBCs is short, and so the body must produce new ones constantly.

Inside the nucleus lies the blueprint that dictates everything a cell will do and all of the products it will make. This information is stored within DNA. The nucleus sends “commands” to the cell via molecular messengers that translate the information from DNA. Each cell in your body (with the exception of germ/sex cells) contains the complete set of your DNA. When a cell divides, the DNA must be replicated so that each new cell receives a full complement of DNA. The following section will explore the structure of the nucleus and its contents, as well as the process of DNA replication.

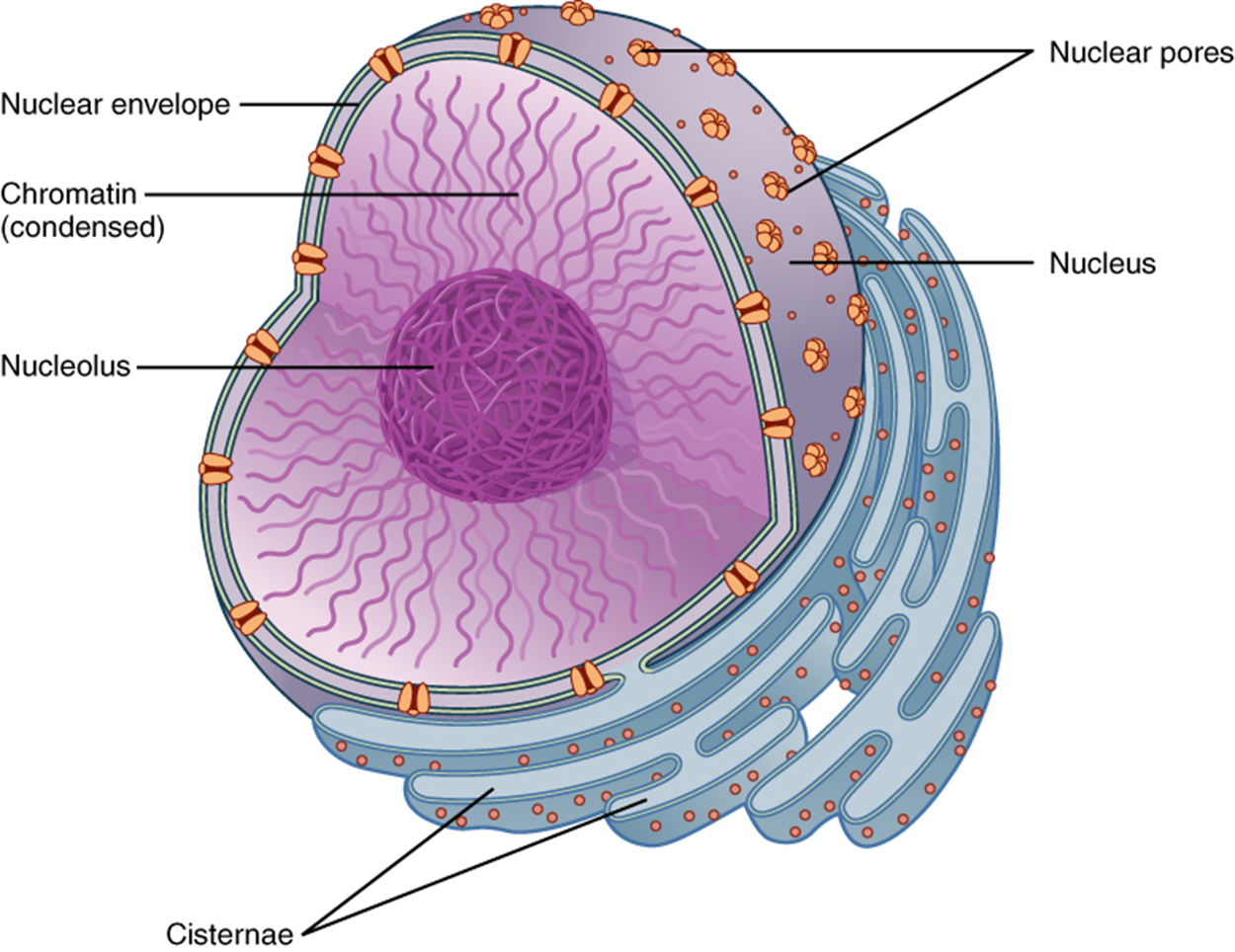

Similar to the mitochondria, the nucleus is surrounded by two phospholipid membranes, an inner and outer membrane, separated by a thin fluid-filled space. In the case of the nucleus, this membrane is called the nuclear envelope. Spanning these two bilayers are nuclear pores. A nuclear pore is a tiny passageway for the passage of materials (proteins, RNA, and solutes) between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Proteins, called pore complexes, line the nuclear pores and regulate the passage of materials into and out of the nucleus.

Inside the nuclear envelope is a gel-like nucleoplasm with solutes that include the building blocks of nucleic acids used to make DNA and RNA. There also can be a dark-staining mass often visible under a simple light microscope, called a nucleolus (plural = nucleoli). The nucleolus is a region of the nucleus that is responsible for manufacturing the RNA necessary for the construction of ribosomes. Once synthesized, newly made ribosomal subunits exit the cell’s nucleus through the nuclear pores.

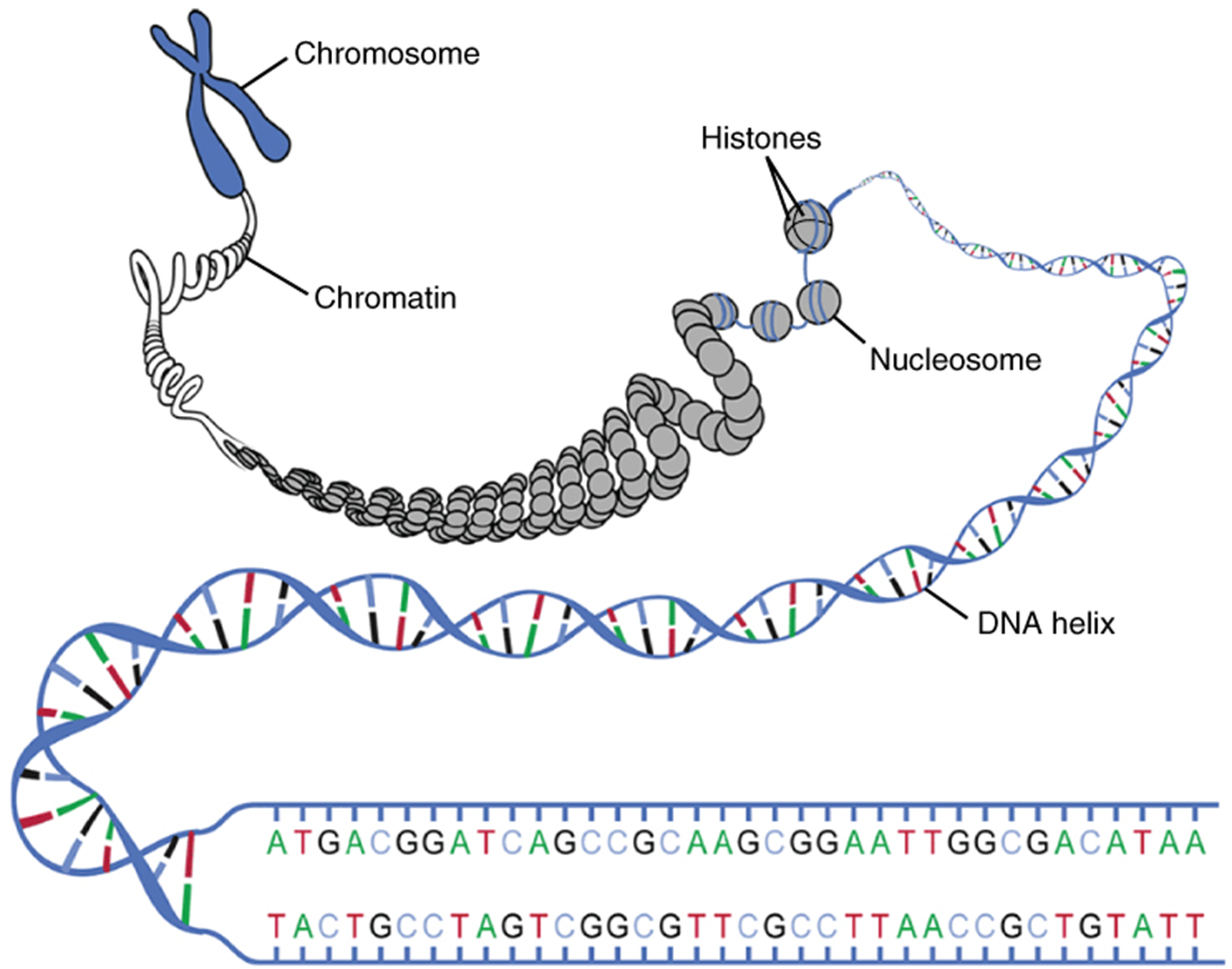

The genetic instructions that are used to build and maintain an organism are arranged in an orderly manner in strands of DNA and stored inside the nucleus. In order to fit all of these coded instructions into such a small space, DNA has a highly coordinated method of compacting to limit the space it takes up.

In order for an organism to grow, develop, and maintain its health, cells must reproduce themselves by dividing to produce two new cells. In order for each cell to have the full set of coded genetic instructions, each cell must contain a full complement of DNA as found in the original cell. Billions of new cells are produced in an adult human every day. Only very few cell types in the body do not divide—including nerve cells, skeletal muscle fibers, and cardiac muscle cells.

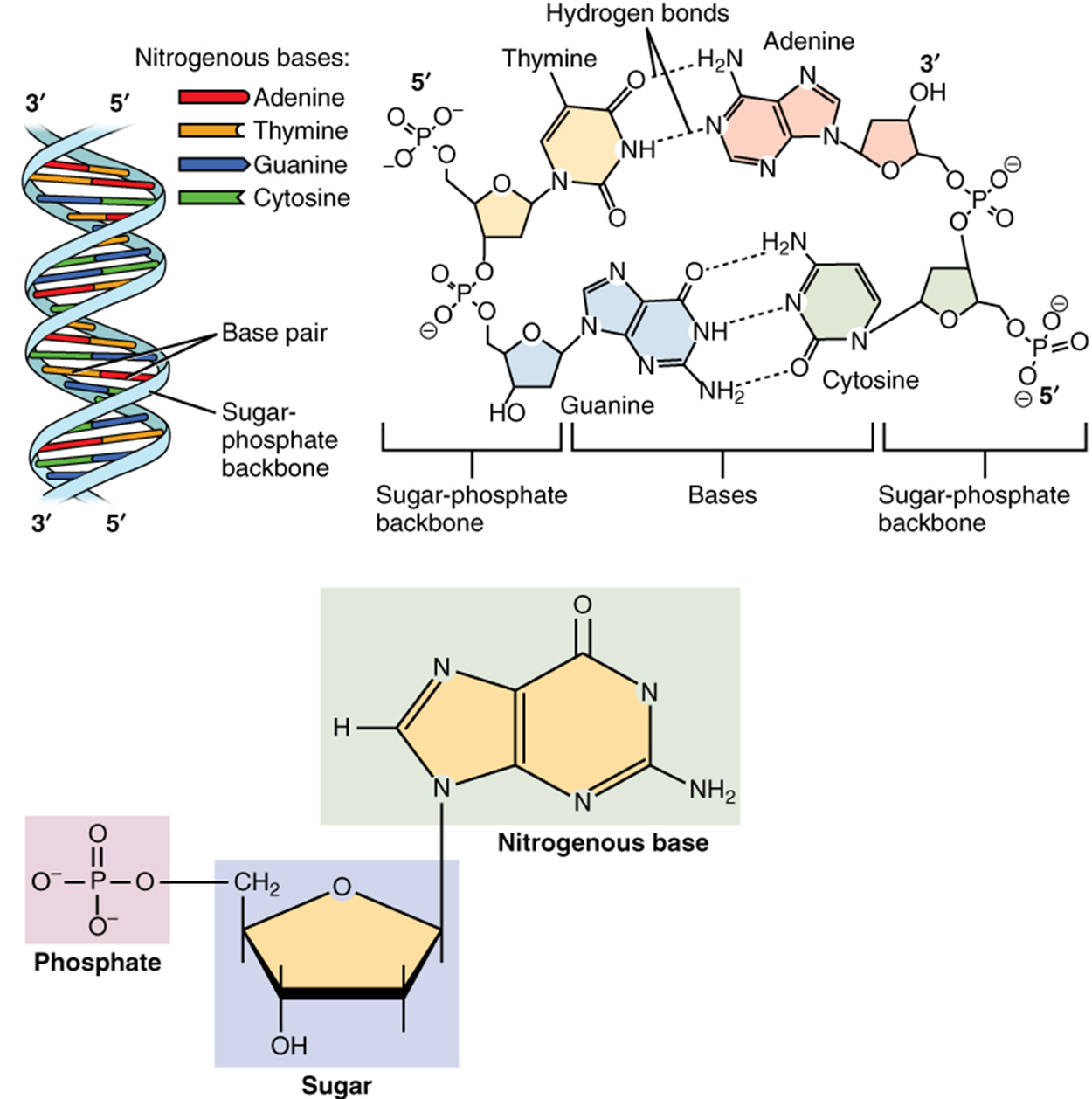

Recall that each DNA strand is a polymer of nucleotides and is formed by a deoxyribose sugar and phosphate backbone with bases projecting inward. The two sides of the twisted ladder that double helix DNA forms are not identical, but are complementary. These two backbones are bonded to each other across pairs of protruding bases, each bonded pair forming one “rung,” or cross member. The four DNA bases are adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). Because of their shape and charge, the two bases that compose a pair always bond together. Adenine always binds with thymine, and cytosine always binds with guanine. The particular sequence of bases along the DNA molecule determines the genetic code. Therefore, if the two complementary strands of DNA were pulled apart, you could infer the order of the bases in one strand from the bases in the other, complementary strand. For example, if one strand has a region with the sequence AGTGCCT, then the sequence of the complementary strand would be TCACGGA.

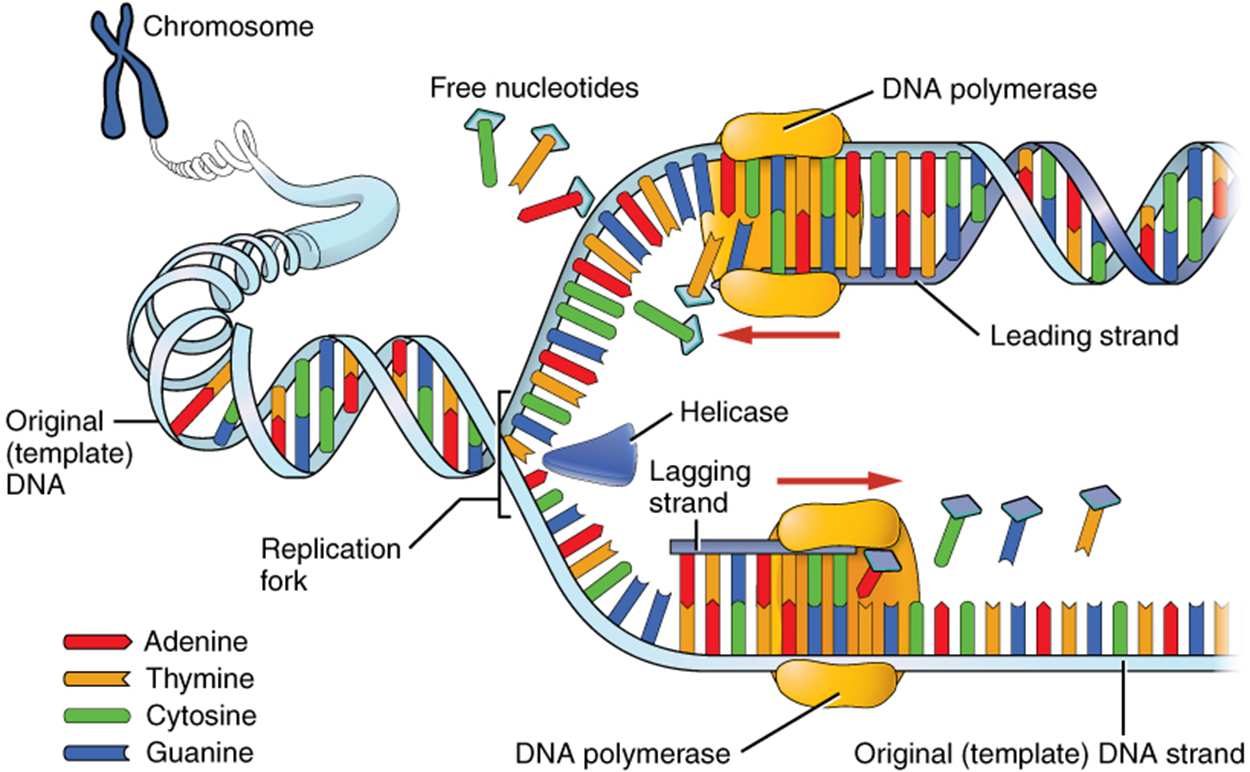

DNA replication is the process of making a copy of DNA that occurs before cell division can take place. After a great deal of debate and experimentation, the general method of DNA replication was deduced in 1958 by two scientists in California: Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl. This method is illustrated and described below.

Stage 1: Initiation. The two complementary strands are separated, much like unzipping a zipper. Special enzymes, including helicase, untwist and separate the two strands of DNA.

Stage 2: Elongation. Each strand becomes a template along which a new complementary strand is built. DNA polymerase brings in the correct bases to complement the template strand, synthesizing a new strand base by base. A DNA polymerase is an enzyme that adds free nucleotides to the end of a chain of DNA which makes a new double strand. This growing strand continues to be built until it has fully complemented the template strand.

Stage 3: Termination. Once the two original strands are bound to their own, finished, complementary strands, DNA replication is stopped and the two new identical DNA molecules are complete.

Each new DNA molecule contains one strand from the original molecule and one newly synthesized strand. The term for this mode of replication is “semiconservative,” because half of the original DNA molecule is conserved in each new DNA molecule. This process continues until the cell’s entire genome, the entire complement of an organism’s DNA, is replicated. As you might imagine, it is very important that DNA replication takes place precisely so that new cells in the body contain the exact same genetic material as their parent cells. Mistakes made during DNA replication, such as the accidental addition of an inappropriate nucleotide, have the potential to render a portion of the genetic code dysfunctional or useless. Fortunately, there are mechanisms in place to minimize such mistakes. A DNA proofreading process enlists the help of special enzymes that scan the newly synthesized molecule for mistakes and corrects them. Once the process of DNA replication is complete, the cell is ready to divide. You will explore the process of cell division later in a future lesson.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT HTTPS://OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.