Table of Contents |

At the end of World War I, Congress refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. As a result, the United States did not participate in the League of Nations—an international body that sought to resolve disputes through discussion and negotiation.

The fact that many Americans during the 1920s and 1930s were wary of international involvement has led some historians (and students) to conclude that the United States was isolationist or that it sought to withdraw from global affairs entirely during this period.

Some historians challenge this conclusion. The United States continued to oversee the affairs of Latin American nations during this period. As American troops withdrew from countries they temporarily occupied, the United States established relations with several dictators in the region. These leaders imposed authoritarian rule on their nations and enacted policies favorable to U.S. economic and agricultural interests.

In European affairs, the United States avoided agreements that might limit its ability to act independently. Some historians argue that this was in keeping with the foreign policy tradition of unilateralism.

In 1928, the United States and 14 European nations signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which declared war to be an international crime. One of the reasons that the United States supported the pact was that it did not require signatory nations to assist each other in the event of a military attack.

A series of international crises during the 1930s, each linked to the increasing militarism of Italy, Germany, and Japan, tested America’s desire for nonintervention and independence in foreign policy.

Unlike the United States, many European nations struggled in the aftermath of World War I. In Italy and Germany, the economic and political climate supported the growth of nationalist, militaristic regimes.

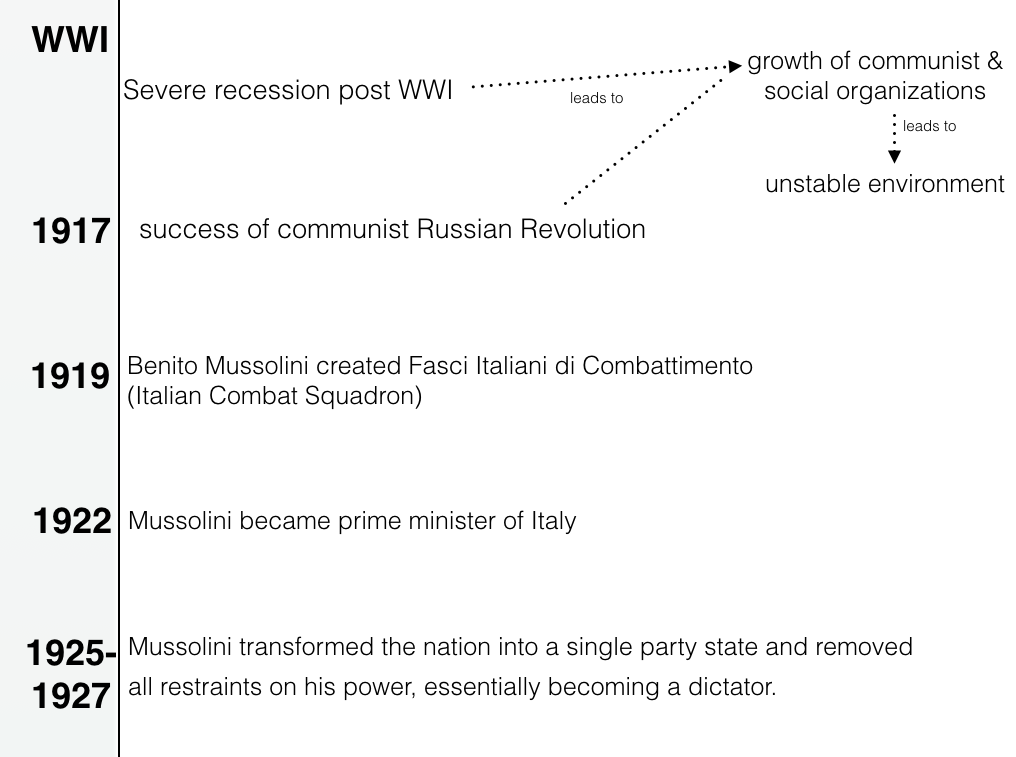

Italy’s economy experienced a severe recession following World War I. This poor economic situation, combined with the Russian Revolution of 1917, created an unstable environment that facilitated the rise of Benito Mussolini.

Mussolini’s Fasci Italiani di Combattimento articulated a political philosophy known as fascism. With support from major Italian industrialists and the king, who feared the prospects of a communist revolution, Mussolini became prime minister of Italy in 1922. By 1927, he had removed all restraints on his power to become the dictatorial leader of the nation.

Similar circumstances contributed to the rise of the National Socialist (or Nazi) Party, led by Adolf Hitler, in Germany.

Following World War I, German politics was fragmented by partisan divisions. The economy was devastated by the severe reparations that Germany owed to the Allied Powers according to the Treaty of Versailles. As a result, Germans resented the Allied Powers, particularly France and Great Britain. These conditions led to the growth of the German Communist Party, which frightened wealthy and middle-class Germans.

The Nazi Party gained many followers during the Great Depression, when Germany, like other industrialized nations, suffered from decreased production, declining consumption, and increased unemployment.

EXAMPLE

Nearly 30% of the German workforce was unemployed in 1932.By early 1933, the Nazis had become the largest party in the German legislature. As the economy deteriorated and the fear of communist revolution spread, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as chancellor (i.e., the head of government) in January 1933. In a subsequent election, Nazis in the legislature passed an Enabling Act, which granted Hitler dictatorial powers.

Hitler blamed Jews and ethnic minorities for Germany’s decline and promised to return the country to greatness. He revitalized German armed forces and began an aggressive program of territorial expansion that violated the Treaty of Versailles, as shown in the table below.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1935 | Germany enacted the Nuremberg Laws, which deprived Jews of German citizenship and associated rights. |

| 1936 | Hitler sent army units to the Rhineland (which borders France). According to the Treaty of Versailles, this region was to remain a demilitarized zone. |

| March 1938 | Germany invaded and occupied Austria. |

| November 9, 1938 | Nazi gangs raided and destroyed Jewish homes/businesses/synagogues—an event that came to be known as Kristallnacht (the night of the broken glass). |

The European powers responded to Germany’s acquisition of the Sudetenland (a region of Czechoslovakia with a large German population) in the summer of 1938 with a policy of appeasement.

At a conference in Munich in September 1938, Great Britain’s prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, and France’s prime minister, Édouard Daladier, accepted German occupation of the Sudetenland, hoping that Hitler’s appetite for expansion would be satisfied with this concession.

Not long after the Sudetenland agreement, however, Germany occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia and prepared to expand further into Eastern Europe.

Unlike Germany or Italy, Japan was a prosperous nation at the end of World War I. It had developed a modern, industrial, capitalist economy like the United States and other industrial powers. Like Mussolini and Hitler, however, Japanese political and military leaders viewed the spread of communism with great concern, especially in China, where civil war raged during the late 1920s. Japan also sought to acquire territory that would provide raw materials for its industrial economy. In 1931, Japanese troops occupied the northeastern region of China known as Manchuria.

In 1936, Japan and Germany signed a mutual defense treaty in which they pledged to support each other in their expansionist projects. Italy joined the pact a year later, forming the foundation of a military alliance known as the Axis Powers.

Japan invaded China in 1937. Chinese troops suffered significant defeats, and Japanese conduct sparked an international outcry. When Japan captured the city of Nanjing (also known as Nanking) in December of 1937, Japanese soldiers raped Chinese women and massacred approximately 300,000 Chinese prisoners of war and civilians.

The United States was alarmed by the rise of fascism in Europe and Japanese militarism in the Pacific. However, many Americans supported nonintervention, also known as neutrality, for several reasons:

In 1934 and 1935, the Nye Commission, headed by Senator Gerald P. Nye of North Dakota, held hearings in which it concluded that a small group of bankers and industrialists had pressured Woodrow Wilson into deciding to enter the First World War. This group profited from the war by making loans or selling arms and ammunition to the Allied Powers.

The findings of the Nye Commission indicated that a profit motive was behind American entry into World War I rather than a desire to win peace and spread democracy. Based on its findings, the commission concluded that the United States should not be drawn into another international dispute.

Although President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Congress were aware of the Nazi persecution of Jews, they failed to relax immigration restrictions that could have allowed more refugees to enter the United States. Anti-Semitism in the United States, embodied by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan during the 1920s, limited the desire of many Americans to relieve the growing refugee crisis.

EXAMPLE

In 1939, when German refugees aboard the S.S. St. Louis, most of them Jews, were refused permission to land in Cuba and turned to the United States for help, the State Department informed them that the immigration quota for Germany had already been filled. They were forced to return to Europe.Additional Resource

Visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum to listen to audio interviews of 48 Holocaust survivors.

During the second half of the 1930s, Congress passed a series of Neutrality Acts (see the table below) to limit American involvement overseas.

| Neutrality Acts | |

|---|---|

| The Neutrality Act of 1935 | Prohibited the sale of arms to warring nations |

| The Neutrality Act of 1936 | Prohibited American banks from loaning money to countries currently at war |

| The Neutrality Act of 1937 | Forbade the transportation of weapons or passengers to warring nations on American ships; also prohibited American citizens from traveling on the ships of nations at war |

Events in Europe forced the United States to reconsider neutrality and to develop a foreign policy based on international cooperation.

On September 1, 1939, Germany began a Blitzkrieg, or “lightning war,” against Poland. Swift, surprise attacks by infantry, tanks, and aircraft quickly overwhelmed the Polish defenders. Finally realizing that Hitler could not be trusted and that his nation’s territorial demands could not be satisfied, Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. The European phase of World War II had begun.

From that point on, President Roosevelt worked to convince Congress and the American people that assisting Great Britain and the other Allies was in the nation’s best interests.

In November 1939, Roosevelt succeeded in altering the Neutrality Acts by implementing a policy known as cash and carry.

The situation was dire for the Allies during the early years of the war.

EXAMPLE

During its spring offensive in 1940, the German army conquered much of Scandinavia and defeated France in 6 weeks, leaving Great Britain to stand alone against German aggression.

As Europe confronted the Axis Powers, the opponents of American involvement in World War II formed the America First Committee.

The committee included prominent citizens (e.g., Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh) who opposed U.S. involvement for the following reasons:

As the America First Committee argued against American intervention, President Roosevelt worried that Great Britain might be overwhelmed by German forces. The crisis prompted him to run for a third term as president. Roosevelt won the 1940 election over Republican challenger Wendell Wilkie easily. In a December 1940 “fireside chat,” he announced that the United States would serve as an “arsenal of democracy” for Great Britain and the other Allies, by providing them with the supplies they needed to fight the Axis Powers.

In his State of the Union address in January 1941, Roosevelt outlined war objectives for the Allies by outlining the “four freedoms”:

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the “Four Freedoms”

“The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want—which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear—which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.”

By March 1941, with Great Britain nearly bankrupt and concern growing over its ability to defend itself, Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act.

The Lend-Lease Act ended America’s neutrality. Through Lend-Lease, the United States transported billions of dollars in aid and material to Great Britain and other Allies. Congress also began to increase annual expenditures for national defense. By the fall of 1941, the United States was fully committed to doing all that it could to contain Nazi aggression—short of direct military intervention.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Four Freedoms Speech, January 6, 1941, Retrieved from the Miller Center on 5/1/17: bit.ly/2qpnBwx