Table of Contents |

Remember that skeletal muscles are voluntary muscles: You can control them. How does your thought to flex your arm get translated into movement? How does the signal get from your brain to your biceps?

Motor neurons carry the signal from your brain to specific muscle fibers, telling the sarcomeres within those muscle fibers when to contract.

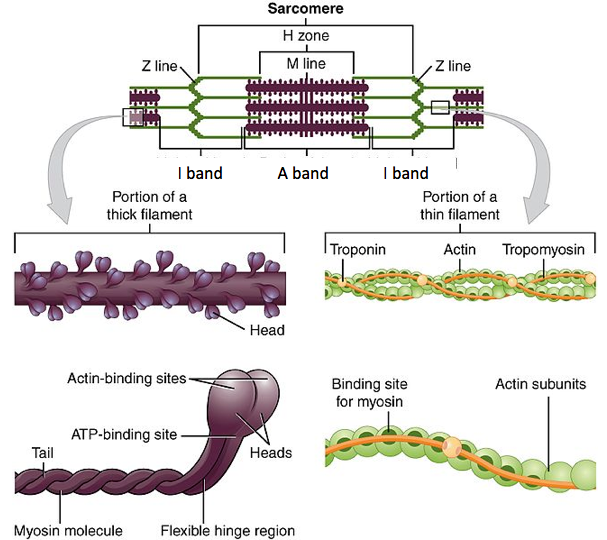

Before discussing the steps involved in a muscle contraction, let's review the structure of a sarcomere. Myosin is referred to as the thick filament in a sarcomere. Myosin heads will attach to actin, the thin filaments, pulling the Z-lines of a sarcomere closer together. This allows for the shortening of that sarcomere, which in turn causes the shortening of the muscle fiber, and therefore a muscle contraction.

What prevents myosin from binding to actin when there's no signal to contract? After all, we don't want our muscles to randomly contract; we'd never be able to stop twitching! Troponin and tropomyosin are proteins that are found on actin filaments; they regulate when myosin can bind to actin and cause the sarcomere to contract.

As you previously learned, all living cells have a membrane potential, which is a difference in electrical charge across their cell membrane. This electrical gradient is created by the presence of an uneven amount of positive and negative ions (charged atoms) on either side of the membrane. For instance, more positive ions on the outside of a cell than inside causes the outside to be positively charged, while the inside is negatively charged. Ion channels in the membrane can move ions such as sodium (Na) and potassium (K) into or out of the cell by active membrane transport.

Both neurons and muscle cells are electrically excitable, meaning they can use their membrane potential to generate electrical signals that can travel along a cell membrane as a wave. The inside of their membranes is usually around -60 to -90 mV (mv = millivolts, 1/1000th of a volt) relative to the outside. Although the currents generated by ions moving through these channel proteins are very small, they form the basis of both neural signaling and muscle contraction.

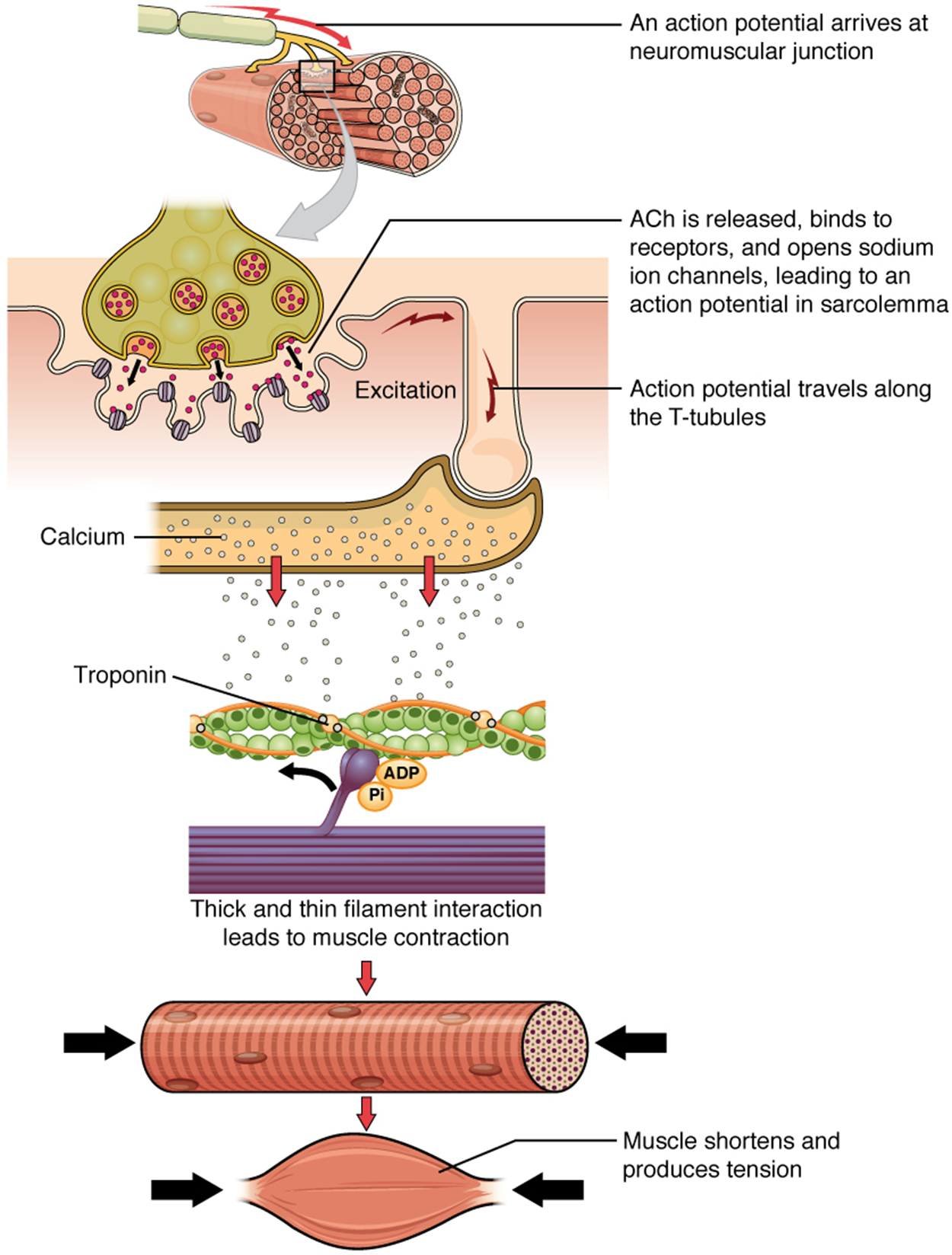

In order for a muscle fiber to contract, its membrane must first be “excited,” or electrically activated enough to generate an electrical signal. This means that these two events, excitation and contraction, are linked, otherwise referred to as excitation–contraction coupling. In skeletal muscle, the sequence of events that occurs always begins with signals from the motor neuron, a neuron that causes movement in the body.

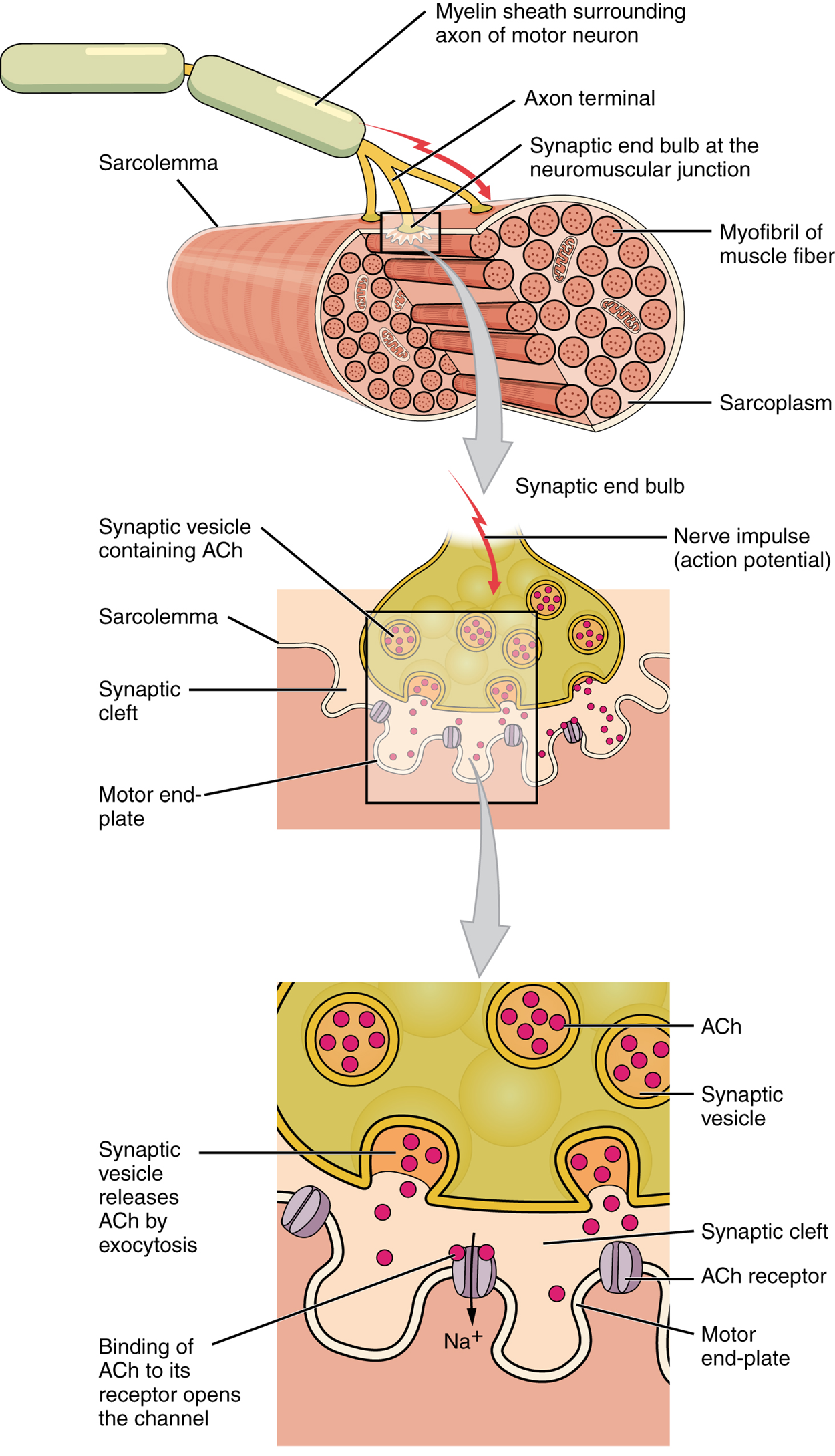

Before you can learn the steps of excitation–contraction coupling, it is important to review the anatomy of a neuron. Recall that a neuron is composed of a cell body, or soma, with two types of processes that extend outwards. Dendrites branch off of the cell body and monitor the electrochemical activity in their surrounding area, bringing electrical signals into the soma. The axon extends away from the cell body and propagates an electrical signal onto the next cell. At the end of the axon are axon terminals (terminus, ending), which form connections with and transfer electrochemical signals to other cells.

The series of events begins when an electrical signal travels along the axon of a neuron and reaches the axon terminal. Here, the axon terminal meets the muscle fiber and forms a connection called a neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ consists of the axon terminal of the neuron, a portion of the sarcolemma called the motor end plate, and the space between them. These two cells do not form a physical connection, instead leaving a small gap called a synaptic cleft between them.

The presence of a gap between the axon terminal and the motor end plate means the electrical signal cannot directly transfer from neuron to muscle fiber. Instead, the electrical signal in the neuron must be converted into a chemical signal which travels across the gap. This chemical signal must then be converted back into an electrical signal in the muscle fiber. Because of the electrical and chemical components of the signal, it is referred to as an electrochemical signal.

When the electrical signal arrives at the NMJ, it causes the release of a specific chemical messenger, or neurotransmitter, known as acetylcholine (ACh). The ACh molecules diffuse across the synaptic cleft and bind to ACh receptors located within the motor end plate. Once ACh binds, a channel in the ACh receptor opens, and positively charged sodium ions can pass into the muscle fiber, causing its membrane potential to depolarize, or become less negative. Once a specific threshold of depolarization is met, an electrochemical signal rapidly propagates (spreads) along the sarcolemma to initiate excitation–contraction coupling.

Things happen very quickly in the world of excitable membranes (just think about how quickly you can snap your fingers as soon as you decide to do it). Immediately following the depolarization of the membrane, it repolarizes, reestablishing its original negative membrane potential. Meanwhile, the ACh in the synaptic cleft is degraded and inactivated by an enzyme in the synaptic cleft called acetylcholinesterase (AChE) so that the ACh cannot rebind to a receptor and reopen its channel, which would cause unwanted extended muscle excitation and contraction.

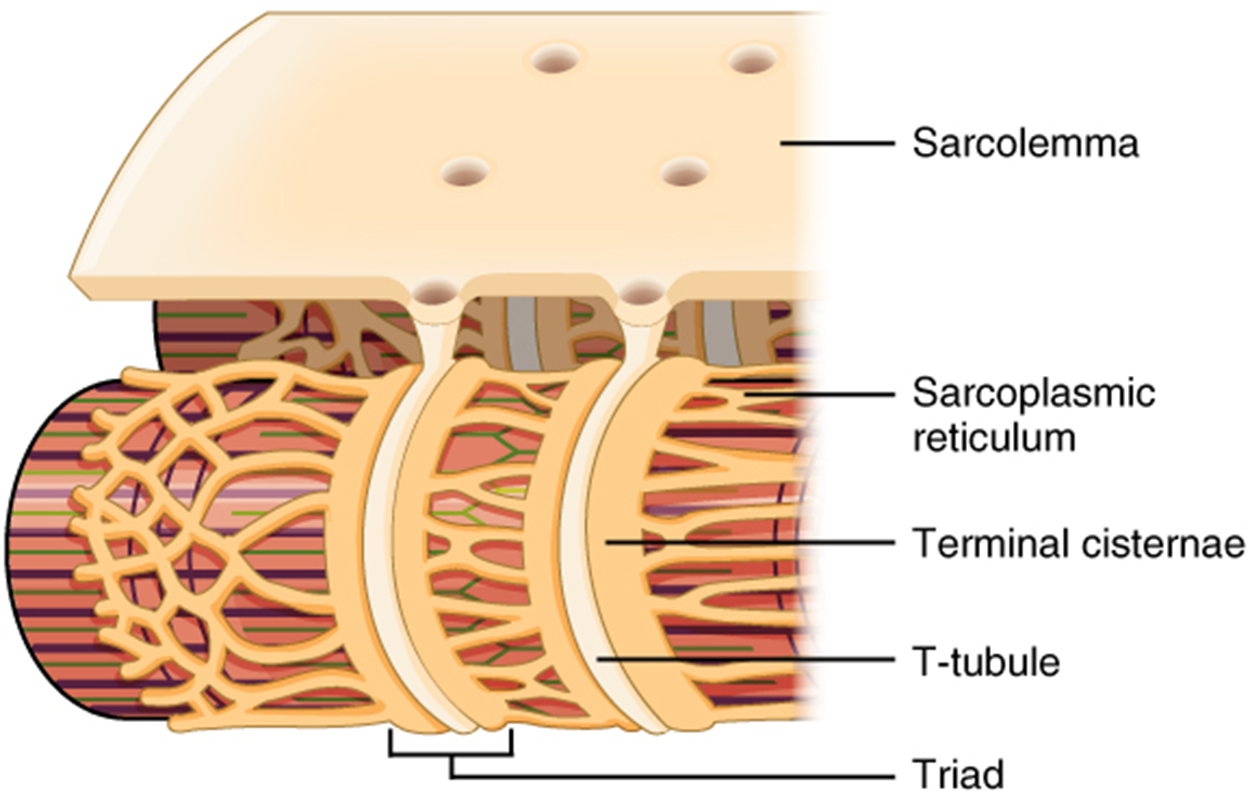

Propagation of an electrochemical signal along the sarcolemma is the excitation portion of excitation–contraction coupling. This excitation triggers the release of calcium ions (Ca²⁺) from its storage in the cell’s sarcplasmic reticulum (SR). For the action potential to reach the membrane of the SR, there are periodic invaginations in the sarcolemma, called transverse tubules, also known as T-tubules. These T-tubules ensure that the membrane can get close to the SR in the sarcoplasm. The arrangement of a T-tubule with the membranes of SR on either side is called a triad. The triad surrounds the cylindrical myofibril, which contains a protein called troponin that has a calcium-binding site. The release of calcium will initiate another series of events known as the muscle contraction cycle, which will shorten the sarcomere and therefore the muscle.

Recall that when a muscle fiber (cell) is electrically activated (i.e., excited) at the NMJ, this excitation results in the release of Ca²⁺ by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). The Ca²⁺ released by the SR initiates a repetitive series of events called the muscle contraction cycle, which leads to the shortening of a muscle.

Recall that the proteins that form thin and thick filaments contain four key binding sites:

As summarized in the image below, the electrochemical signal from a motor neuron causes the excitation of a muscle fiber, which results in the contraction of a muscle fiber. If enough muscle fibers contract within a muscle, sufficient tension can be produced to cause the muscle to shorten.

This series of events will continue to cycle so long as Ca²⁺ ions and ATP remain available or until the muscle reaches its anatomical limit. Note that each thick filament of roughly 300 myosin molecules has multiple myosin heads, and many crossbridges form and break continuously during muscle contraction. Multiply this by all of the sarcomeres in one myofibril, all the myofibrils in one muscle fiber, and all of the muscle fibers in one skeletal muscle, so you can understand why so much energy (ATP) is needed to keep skeletal muscles working. In fact, it is the loss of ATP that results in the rigor mortis observed soon after someone dies. With no further ATP production possible, there is no ATP available for myosin heads to detach from the actin-binding sites, so the crossbridges stay in place, causing rigidity in the skeletal muscles.

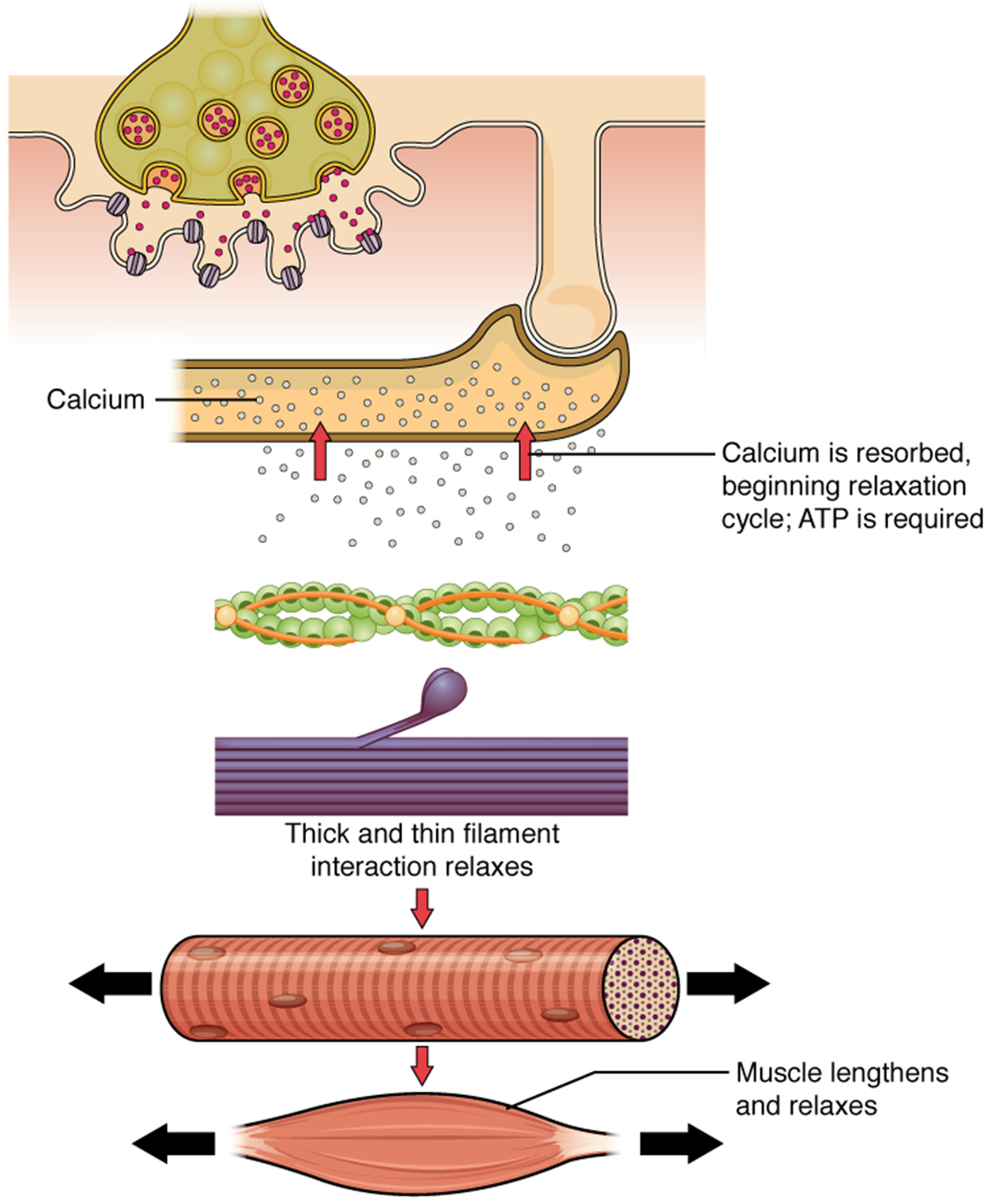

When the body relaxes a skeletal muscle, all of the events that led to a muscle contraction reverse.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.