Table of Contents |

You have learned about three major types of muscles, which are summarized in the table below. In this lesson, we will focus on skeletal muscle contraction. Keep in mind that there are important differences in structure and function, including mechanisms of contraction, in each muscle type.

| Comparison of Structure and Properties of Muscle Tissue Types | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | Histology | Function | Location |

| Skeletal | Long cylindrical fiber, striated, many peripherally located nuclei | Voluntary movement, produces heat, protects organs | Attached to bones and around entrance points to body (e.g., mouth, anus) |

| Cardiac | Short, branched, striated, single central nucleus | Contracts to pump blood | Heart |

| Smooth | Short, spindle-shaped, no evident striation, single nucleus in each fiber | Involuntary movement, moves food, involuntary control of respiration, moves secretions, regulates flow of blood in arteries by contraction | Walls of major organs and passageways |

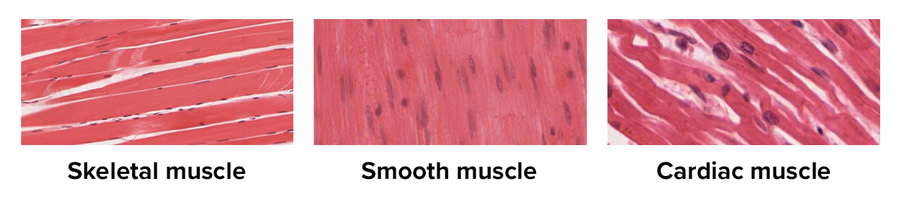

The image below shows the three types of muscle tissue for you to compare. Note the striated appearance of the skeletal muscle shown on top, the lack of striations in the smooth muscle shown in the middle, and the branched appearance of the cardiac muscle on the bottom.

All three muscle tissues have some properties in common; they all exhibit a quality called excitability as their plasma membranes can change their electrical states (from polarized to depolarized) and send an electrical wave called an action potential along the membrane. Note that cells have a resting membrane potential representing a difference in charge across the membrane; during an action potential, charged species (ions) cross the membrane to reverse this charge from negative to positive.

While the nervous system can influence the excitability of cardiac and smooth muscle to some degree, skeletal muscle completely depends on signaling from the nervous system to work properly. On the other hand, both cardiac muscle and smooth muscle can respond to other stimuli, such as hormones and local stimuli.

The muscles all begin the actual process of contracting (shortening) when a protein called actin is pulled by a protein called myosin. This occurs in striated muscle (skeletal and cardiac) after specific binding sites on the actin have been exposed in response to the interaction between calcium ions  and proteins (troponin and tropomyosin) that “shield” the actin-binding sites.

and proteins (troponin and tropomyosin) that “shield” the actin-binding sites.  also is required for the contraction of smooth muscle, although its role is different: here

also is required for the contraction of smooth muscle, although its role is different: here  activates enzymes, which in turn activate myosin heads. All muscles require adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used to store energy that can power biological activities, to continue the process of contracting, and they all relax when the

activates enzymes, which in turn activate myosin heads. All muscles require adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is used to store energy that can power biological activities, to continue the process of contracting, and they all relax when the  is removed and the actin-binding sites are re-shielded.

is removed and the actin-binding sites are re-shielded.

A muscle can return to its original length when relaxed due to a quality of muscle tissue called elasticity. It can recoil back to its original length due to elastic fibers. Muscle tissue also has the quality of extensibility; it can stretch or extend. Contractility allows muscle tissue to pull on its attachment points and shorten with force.

Remember that differences among the three muscle types include the microscopic organization of their contractile proteins—actin and myosin. The actin and myosin proteins are arranged very regularly in the cytoplasm of individual muscle cells (fibers) in both skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle, which creates a pattern, or stripes, called striations. The striations are visible with a light microscope under high magnification. Skeletal muscle fibers are multinucleated structures that compose the skeletal muscle. Cardiac muscle fibers each have one to two nuclei and are physically and electrically connected to each other so that the entire heart contracts as one unit (called a syncytium).

Now that you know the basics of muscle contraction, it’s time to explore the process in more detail.

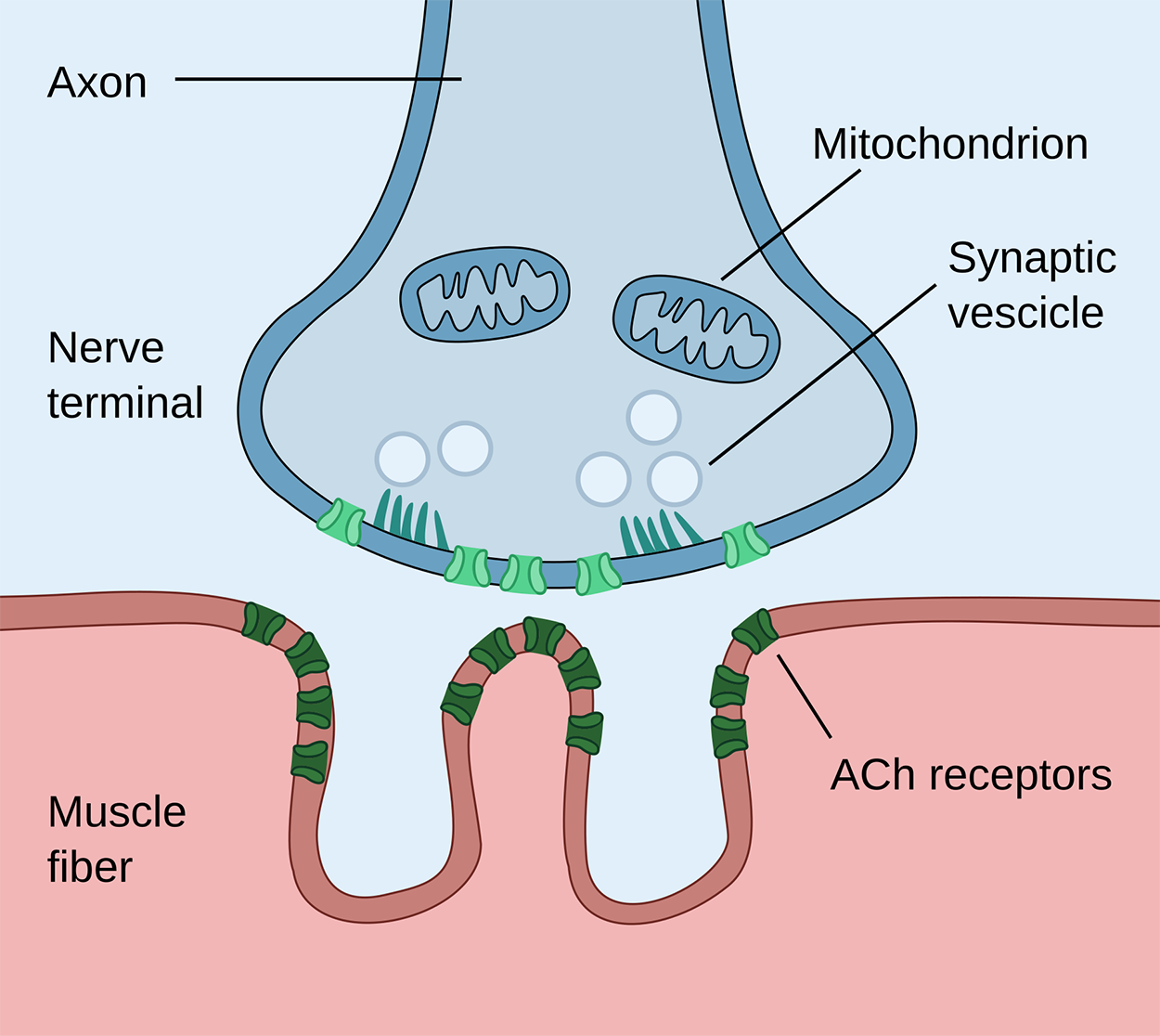

A neuromuscular junction is the place where a neuron meets a muscle cell. When an action potential reaches the neuromuscular junction, a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine (ACh) is released.

The figure below shows a neuromuscular junction. The axon is the part of the neuron that carries information to the nerve terminal, where synaptic vesicles are triggered to release their contents (ACh) into the small gap between the neuron and the muscle cell (called a synapse). ACh binds to receptors on the nearby muscle cell.

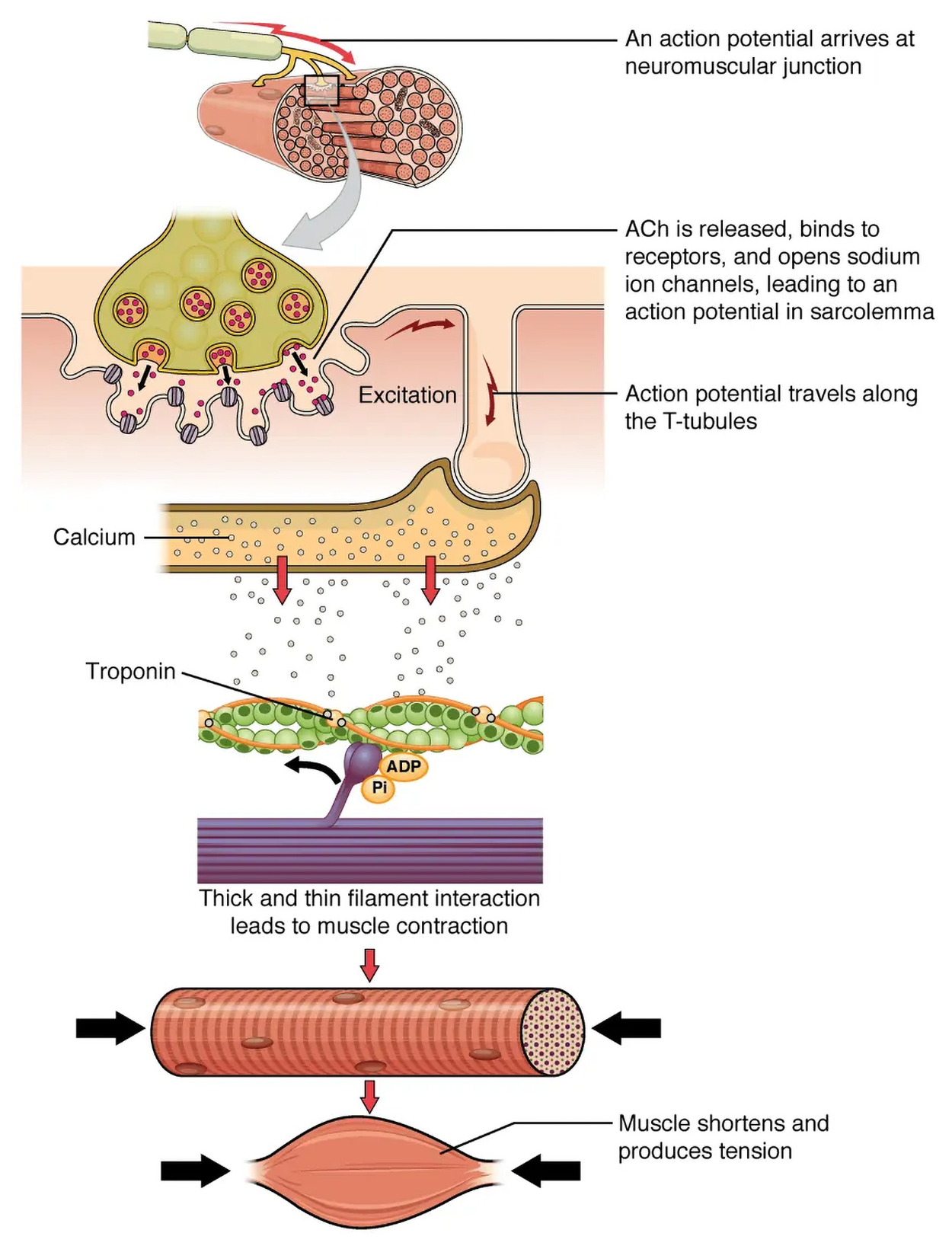

The sequence of events that result in the contraction of an individual muscle fiber begins with this signal, the release of ACh from a motor neuron (a neuron that sends a signal from the brain, as opposed to a sensory neuron that carries information to the brain). The local membrane of the muscle fiber will depolarize as positively charged sodium ions  enter, triggering an action potential that spreads to the rest of the membrane, which will depolarize, including the T-tubules. T-tubules are tubular folds of membrane that penetrate into the cell to rapidly spread the depolarization.

enter, triggering an action potential that spreads to the rest of the membrane, which will depolarize, including the T-tubules. T-tubules are tubular folds of membrane that penetrate into the cell to rapidly spread the depolarization.

Depolarization triggers the release of calcium ions  from storage in a membranous structure called the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which is a specialized form of an organelle called the endoplasmic reticulum. The

from storage in a membranous structure called the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which is a specialized form of an organelle called the endoplasmic reticulum. The  then binds to troponin, causing the troponin complex to move tropomyosin, exposing a myosin-binding site on actin. A part of myosin called the myosin head binds, and this initiates contraction, which is sustained by ATP. As long as

then binds to troponin, causing the troponin complex to move tropomyosin, exposing a myosin-binding site on actin. A part of myosin called the myosin head binds, and this initiates contraction, which is sustained by ATP. As long as  ions remain in the sarcoplasm to bind to troponin, which keeps the actin-binding sites “unshielded,” and as long as ATP is available to drive the cross-bridge cycling and the pulling of actin strands by myosin, the muscle fiber will continue to shorten to an anatomical limit. You will learn more about this process in the next section.

ions remain in the sarcoplasm to bind to troponin, which keeps the actin-binding sites “unshielded,” and as long as ATP is available to drive the cross-bridge cycling and the pulling of actin strands by myosin, the muscle fiber will continue to shorten to an anatomical limit. You will learn more about this process in the next section.

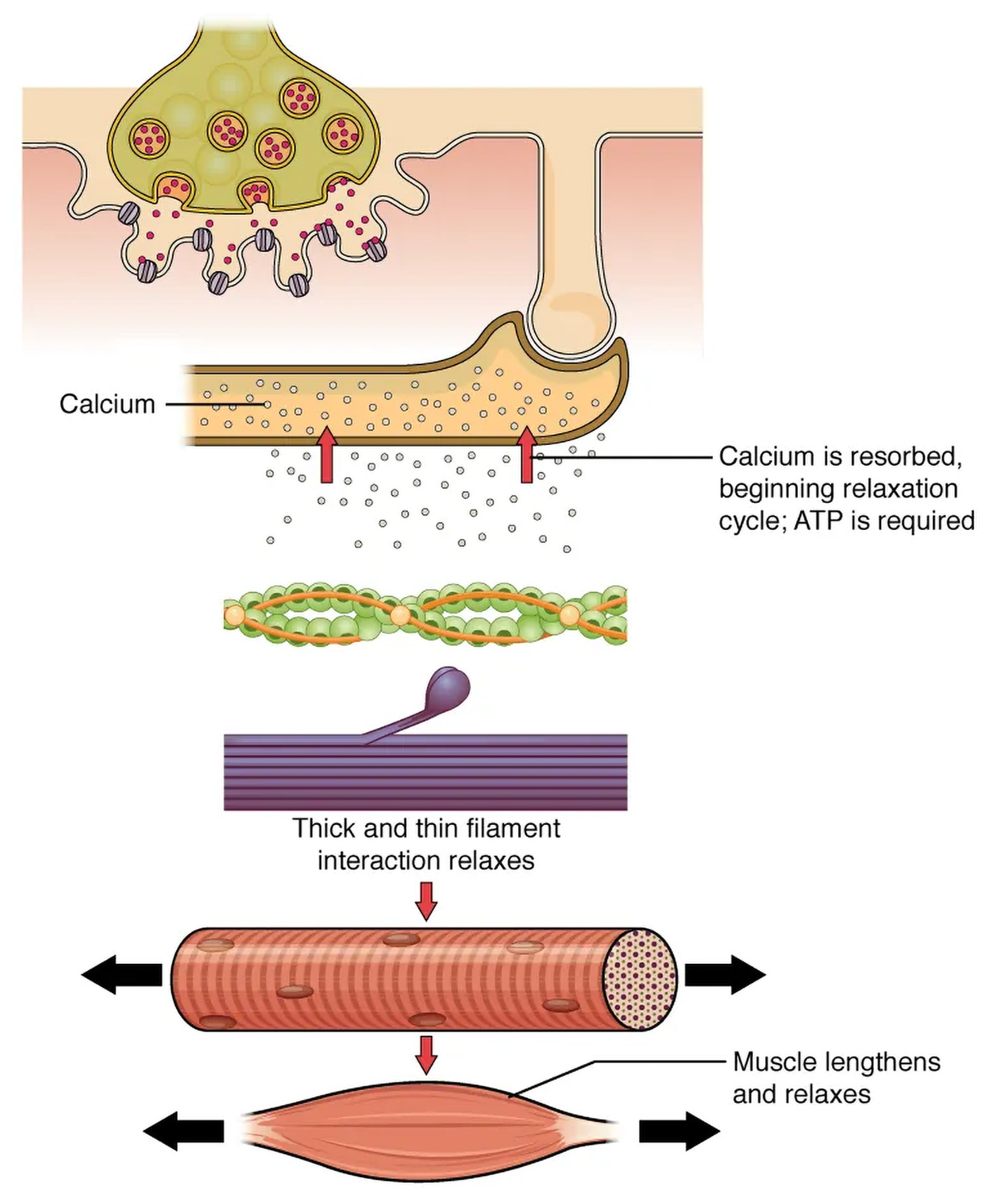

Muscle contraction usually stops when signaling from the motor neuron ends, which repolarizes the sarcolemma (muscle cell membrane) and T-tubules, and closes the channels in the SR that allow calcium to leave.  ions are then pumped back into the SR, which causes the tropomyosin to reshield (or re-cover) the myosin binding sites on the actin strands. A muscle can also stop contracting when it runs out of ATP and becomes fatigued.

ions are then pumped back into the SR, which causes the tropomyosin to reshield (or re-cover) the myosin binding sites on the actin strands. A muscle can also stop contracting when it runs out of ATP and becomes fatigued.

The contraction of a striated muscle fiber occurs as the sarcomeres shorten as myosin heads pull on the actin filaments.

The region where thick and thin filaments overlap has a dense appearance, as there is little space between the filaments. This zone, where thin and thick filaments overlap, is very important to muscle contraction, as it is the site where filament movement starts. Thin filaments, anchored at their ends by the Z-discs, do not extend completely into the central region that only contains thick filaments, anchored at their bases at a spot called the M-line. A myofibril is composed of many sarcomeres running along its length; thus, myofibrils and muscle cells contract as the sarcomeres contract.

IN CONTEXT

Medical societies periodically issue clinical practice guidelines with recommendations for managing particular medical conditions. In 2021, a major clinical guideline was released by the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association (AHA), and other organizations. This guideline provided recommendations for how clinicians should treat patients who present with chest pain. One of the major recommendations is that patients suspected of having a myocardial infarction should have blood work to test cardiac troponin levels. Specifically, high sensitivity cardiac troponin (cTn) levels should be measured (Gulati et al., 2021).

There are three troponin subunits. Troponin C binds to calcium to initiate contraction. Cardiac troponins I and T are the most useful for cardiac diagnostic testing (Gulati et al., 2021).

These troponin levels are valuable because they are normally not present in the blood, but are released by damaged heart muscle. Detection of these biomarkers suggests that further testing is needed to find out what sort of damage is present.

It takes time for troponin levels to rise after heart muscle damage occurs. Therefore, serial measurements are often used to detect rising troponin levels in case a patient has presented too soon after heart muscle injury for elevated troponin to show on blood work.

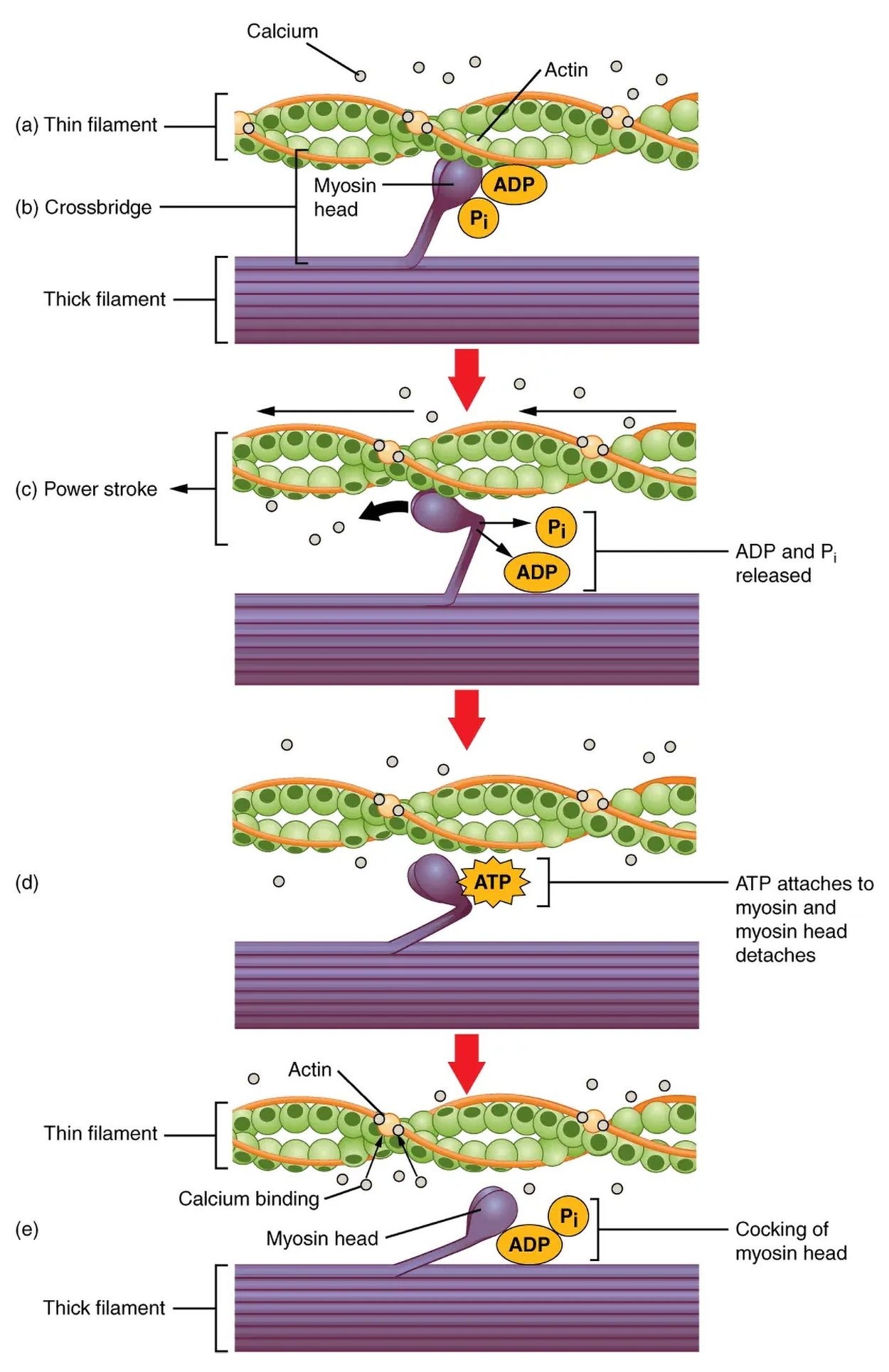

When signaled by a motor neuron, a skeletal muscle fiber contracts as the thin filaments are pulled and then slide past the thick filaments within the fiber’s sarcomeres. This process is known as the sliding filament model of muscle contraction. The sliding can only occur when myosin-binding sites on the actin filaments are exposed by a series of steps that begin with  entry into the sarcoplasm.

entry into the sarcoplasm.

Tropomyosin is a protein that winds around the chains of the actin filament and covers the myosin-binding sites to prevent actin from binding to myosin. Tropomyosin binds to troponin to form a troponin-tropomyosin complex. The troponin-tropomyosin complex prevents the myosin “heads” from binding to the active sites on the actin microfilaments. Troponin also has a binding site for  ions.

ions.

To initiate muscle contraction, tropomyosin has to expose the myosin-binding site on an actin filament to allow cross-bridge formation between the actin and myosin microfilaments. The first step in the process of contraction is for  to bind to troponin so that tropomyosin can slide away from the binding sites on the actin strands. This allows the myosin heads to bind to these exposed binding sites and form cross-bridges. The thin filaments are then pulled by the myosin heads to slide past the thick filaments toward the center of the sarcomere. But each head can only pull a very short distance before it has reached its limit and must be “re-cocked” before it can pull again, a step that requires ATP.

to bind to troponin so that tropomyosin can slide away from the binding sites on the actin strands. This allows the myosin heads to bind to these exposed binding sites and form cross-bridges. The thin filaments are then pulled by the myosin heads to slide past the thick filaments toward the center of the sarcomere. But each head can only pull a very short distance before it has reached its limit and must be “re-cocked” before it can pull again, a step that requires ATP.

For thin filaments to continue to slide past thick filaments during muscle contraction, myosin heads must pull the actin at the binding sites, detach, re-cock, attach to more binding sites, pull, detach, re-cock, etc. This repeated movement is known as the cross-bridge cycle. This motion of the myosin heads is similar to the oars when an individual rows a boat: The paddle of the oars (the myosin heads) pulls are lifted from the water (detach), repositioned (re-cocked), and then immersed again to pull. Each cycle requires energy, which is provided by ATP.

Cross-bridge formation occurs when the myosin head attaches to the actin while adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate  are still bound to myosin.

are still bound to myosin.  is then released, causing myosin to form a stronger attachment to the actin, after which the myosin head moves toward the M-line, pulling the actin along with it. As actin is pulled, the filaments move approximately 10nm toward the M-line. This movement is called the power stroke, as movement of the thin filament occurs at this step. In the absence of ATP, the myosin head will not detach from actin.

is then released, causing myosin to form a stronger attachment to the actin, after which the myosin head moves toward the M-line, pulling the actin along with it. As actin is pulled, the filaments move approximately 10nm toward the M-line. This movement is called the power stroke, as movement of the thin filament occurs at this step. In the absence of ATP, the myosin head will not detach from actin.

One part of the myosin head attaches to the binding site on the actin, but the head has another binding site for ATP. ATP binding causes the myosin head to detach from the actin. After this occurs, ATP is converted to ADP and  by the intrinsic ATPase activity of myosin. The energy released during ATP hydrolysis changes the angle of the myosin head into a cocked position. The myosin head is now in position for further movement.

by the intrinsic ATPase activity of myosin. The energy released during ATP hydrolysis changes the angle of the myosin head into a cocked position. The myosin head is now in position for further movement.

When the myosin head is cocked, myosin is in a high-energy configuration. This energy is expended as the myosin head moves through the power stroke, and at the end of the power stroke, the myosin head is in a low-energy position. After the power stroke, ADP is released; however, the formed cross-bridge is still in place, and actin and myosin are bound together. As long as ATP is available, it readily attaches to myosin, the cross-bridge cycle can recur, and muscle contraction can continue.

Considerable amounts of ATP are required for contraction, and the loss of ATP that results in the rigor mortis is observed soon after someone dies. With no further ATP production possible, there is no ATP available for myosin heads to detach from the actin-binding sites, so the cross-bridges stay in place, causing the rigidity in the skeletal muscles.

Relaxing skeletal muscle fibers begins with the motor neuron, which stops releasing its chemical signal, ACh, into the synapse at the neuromuscular junction. The muscle fiber repolarizes, which closes the gates in the SR where  was being released. ATP-driven pumps move

was being released. ATP-driven pumps move  out of the sarcoplasm back into the SR. This results in the “reshielding” of the actin-binding sites on the thin filaments. Without the ability to form cross-bridges, the muscle fiber loses its tension and relaxes.

out of the sarcoplasm back into the SR. This results in the “reshielding” of the actin-binding sites on the thin filaments. Without the ability to form cross-bridges, the muscle fiber loses its tension and relaxes.

The number of skeletal muscle fibers in a given muscle is genetically determined and does not change. Muscle strength is related to the number of myofibrils and sarcomeres within each fiber. Factors, such as hormones and stress, can increase the production of sarcomeres and myofibrils within the muscle fibers, a change called hypertrophy, which results in the increased mass and bulk in a skeletal muscle. Likewise, decreased use of a skeletal muscle results in atrophy, where the number of sarcomeres and myofibrils disappear (but not the number of muscle fibers).

The basic steps of skeletal muscle contraction are as follows.

There are many important terms that describe the ways that muscles move body parts. You have already encountered some of these. The table below provides an overview of important terms.

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Flexion (FLĔK-shŏn) | Movement that decreases the angle between two bones, such as bending the arm at the elbow. |

| Extension (ĕk-STĔN-shŏn) | Movement that increases the angle between two bones, such as straightening the arm at the elbow. |

| Abduction (ăb-DŬK-shŏn) | Movement of a limb away from the midline of the body. |

| Adduction (ă-DŬK-shŏn) | Movement of a limb toward the midline of the body. |

| Rotation (rō-TĀ-shŏn) | Circular movement around a central point. Internal rotation is toward the center of the body, and external rotation is away from the center of the body. |

| Dorsiflexion (dôr-sĭ-FLĔK-shŏn) | Decreasing the angle of the foot and the leg (i.e., the foot moves upward toward the knee). This movement is the opposite of plantar flexion. |

| Plantar Flexion (PLĂN-tăr FLĔK-shŏn) | Increasing the angle of the foot and leg (i.e., the foot moves downward toward the ground, such as when pressing down on a gas pedal in a car). |

| Supination (sū-pi- NĀ- shŭn) | Movement of the hand or foot turning upward. When applied to the hand, it is the act of turning the palm upwards. When applied to the foot, it is the outward roll of the foot/ankle during normal movement. |

| Pronation (prō-NĀ-shŭn) | Movement of the hand or foot turning downward. When applied to the hand, it is the act of turning the palm downward. When applied to the foot, it is the inward roll of the foot/ankle during normal movement. |

| Eversion (ē-VĔR-zhŭn) | Excessive movement involving turning outward the sole of the foot away from the body’s midline, a common cause of an ankle sprain. |

| Inversion (in-VĔR-zhŭn) | Excessive movement involving turning inward the sole of the foot towards the median plane, a common cause of an ankle sprain. |

The figure below illustrates some of the most important movement terms to know. Make sure that you can distinguish these.

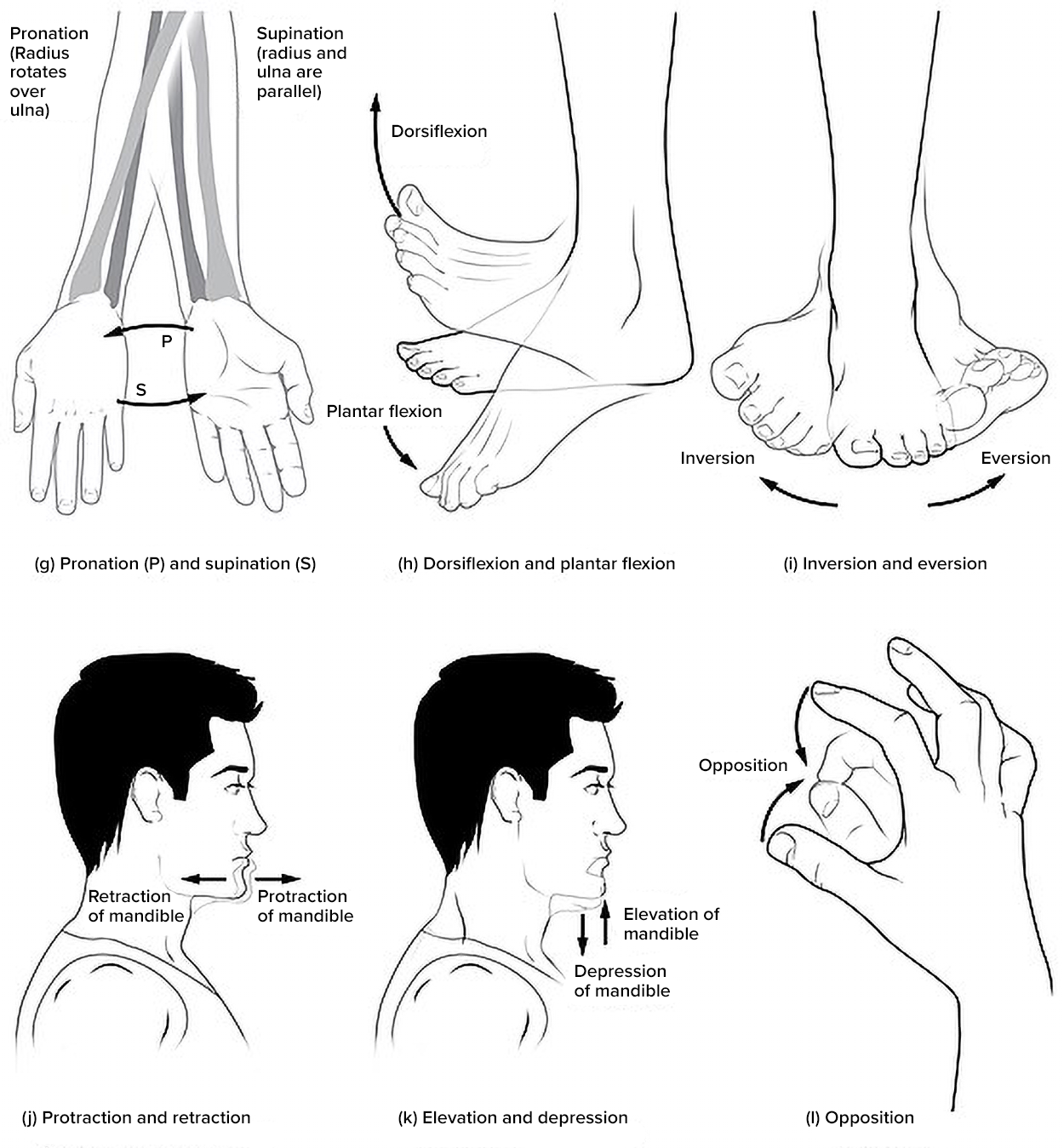

The figure below provides details about movements of the hands, feet, jaw, and fingers.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) “OPEN RN | MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY – 2E” BY ERNSTMEYER & CHRISTMAN AT OPEN RESOURCES FOR NURSING (OPEN RN). (2) "ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E" AT OPENSTAX. ACCESS FOR FREE AT WTCS.PRESSBOOKS.PUB/MEDTERM/ AND OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. LICENSING: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Gulati, M., Levy, P. D., Mukherjee, D., Amsterdam, E., Bhatt, D. L., Birtcher, K. K., Blankstein, R., Boyd, J., Bullock-Palmer, R. P., Conejo, T., Diercks, D. B., Gentile, F., Greenwood, J. P., Hess, E. P., Hollenberg, S. M., Jaber, W. A., Jneid, H., Joglar, J. A., Morrow, D. A., O'Connor, R. E., … Shaw, L. J. (2021). 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 144(22), e368–e454. doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029