Table of Contents |

So far, we have looked at selection statements using if/else logic.

Here is an example of if() and else() statements:

class IfElse {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int grade = 75;

if(grade > 60) {

System.out.println("You passed.");

}

else {

System.out.println("You did not pass.");

}

}

}

We have also reviewed chained selection statements, which use else if() statements.

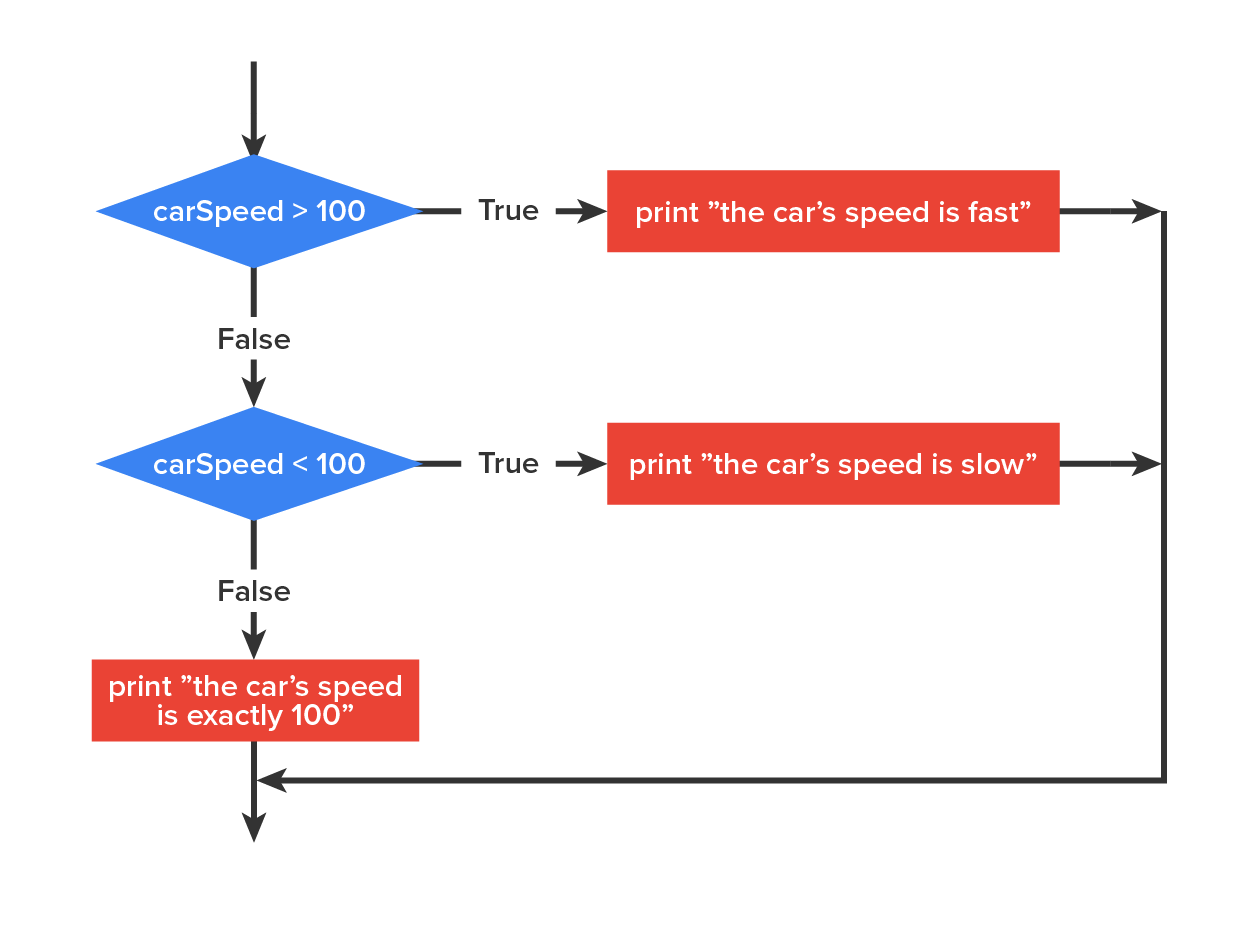

The following flow chart diagrams if/else statements:

Consider the following code example:

import java.util.Scanner;

class CarSpeed {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Scanner input = new Scanner(System.in);

System.out.print("Enter car's speed between 0 and 200: ");

int speed = input.nextInt();

if(speed > 100) {

System.out.println("The car's speed is fast!");

}

else if(speed < 100) {

System.out.println("The car's speed is slow!");

}

else {

System.out.println("The car's speed is exactly 100.");

}

}

}

If the car’s speed is greater than 100, we should get the results of the first condition. The output screen should show The car’s speed is fast!

EXAMPLE

User enters "120" as the car’s speed:

Enter car's speed between 0 and 200: 120

The car's speed is fast!

If the car’s speed is less than 100, we should get the results from the second condition. The output screen should show The car's speed is slow.

EXAMPLE

User enters "99" as the car’s speed:

Enter car's speed between 0 and 200: 99

The car's speed is slow!

If the car’s speed is exactly at 100, the result is the output from the else block. The output screen should show The car's speed is exactly 100.

EXAMPLE

User enters "100" as the car’s speed:

Enter car's speed between 0 and 200: 100

The car's speed is exactly 100.

Selection statements can be nested (nested selection statements), which means that they can appear in one of the branches of another selection statement. This allows for the use of multiple conditions that apply when addressing more complex ways. They can also represent chained selection statements using nested conditionals.

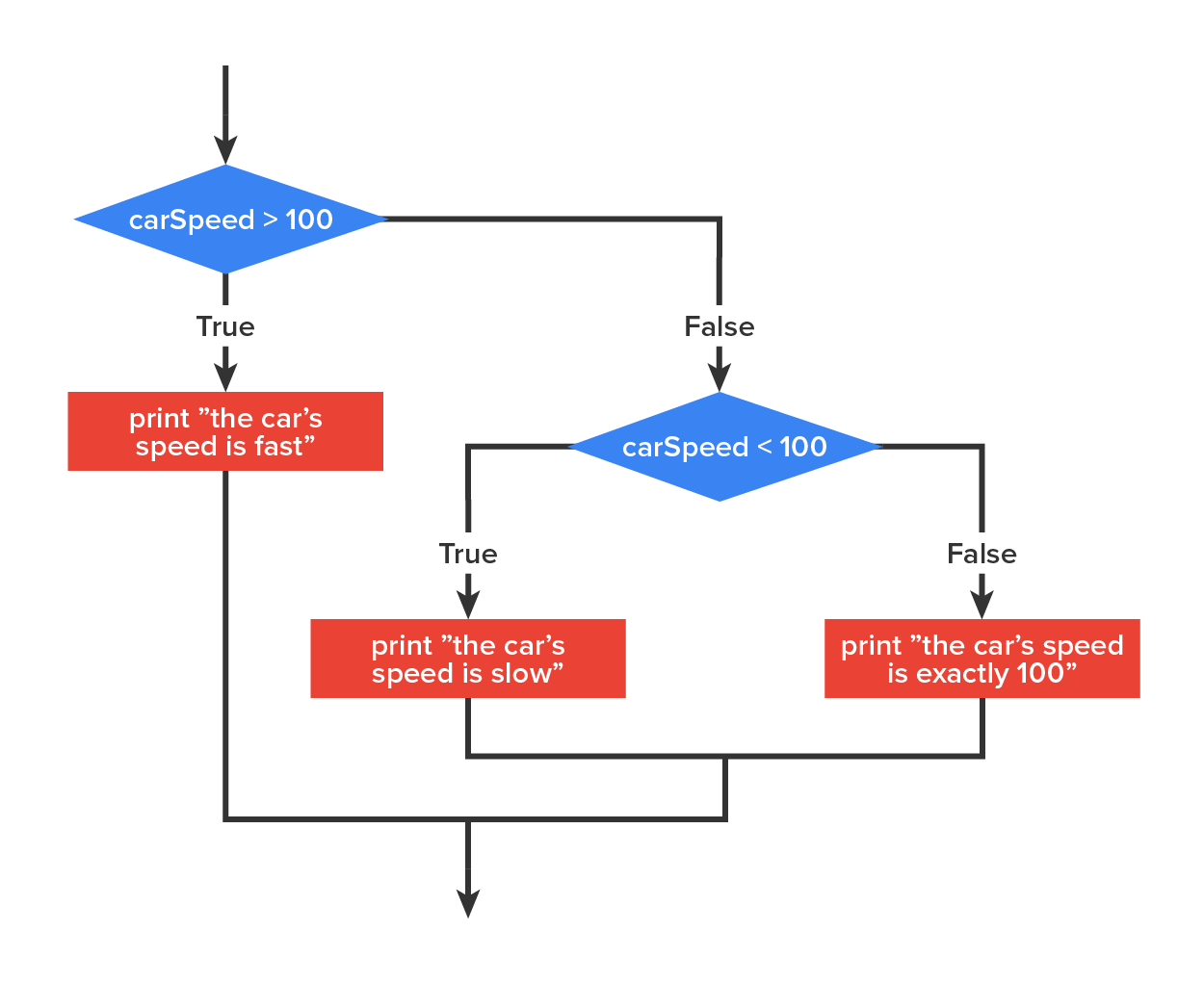

Using the second example in a nested conditional statement, let’s see what a flowchart could look like:

Example of a flow chart of carSpeed with nested conditional code:

As seen, the outer conditional contains two branches. The first branch contains a simple statement. The second branch contains another if() statement, which has two branches of its own. The two branches are both simple statements, although they could have been selection statements as well.

When working with nested selection statements, the correct use of curly brackets to mark the different blocks of code and the indentation of the lines of code in each block become especially important. The curly brackets and indentation help make visible the relationships between the selection statements.

Consider a nested condition in Java code:

import java.util.Scanner;

class CarSpeed {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Scanner input = new Scanner(System.in);

System.out.print("Enter car's speed between 0 and 200: ");

int speed = input.nextInt();

if(speed > 100) {

System.out.println("The car's speed is fast!");

}

else { // Speed not over 100

// Nested selection statements apply

if(speed < 100) {

System.out.println("The car's speed is slow!");

}

else {

System.out.println("The car's speed is exactly 100.");

}

}

}

}

Notice the indentation of the nested blocks for the selection statements. The entire nested if() statement is indented so visually, you can see which else() statement links to which if() statement.

Now, let's try some input tests to see how the nested conditional responds:

EXAMPLE

Car speed fast at 120.

Enter car's speed between 0 and 200: 120

The car's speed is fast!

EXAMPLE

Car speed low at 99.

Enter car's speed between 0 and 200: 99

The car's speed is slow!

EXAMPLE

Car speed exactly at 100.

Enter car's speed between 0 and 200: 100

The car's speed is exactly 100.

Individually, the conditions are very similar to one another. However, the chained conditional statement may logically be easier to follow. In this case, there is only one variable being tracked in the nested conditional statements with the car’s speed.

Below are some examples to demonstrate how the use of nested conditionals or chained conditionals can make the logic easier to follow.

Consider this example of a chained conditional statement that was discussed in a previous tutorial:

class IfElseIf {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int grade = 85;

if(grade > 90) {

System.out.println("You got an A");

}

else if(grade > 80) {

System.out.println("You got a B");

}

else if(grade > 70) {

System.out.println("You got a C");

}

else if(grade > 60) {

System.out.println("You got a D");

}

else if(grade <= 60) {

System.out.println("You got a F");

}

}

}

The else() statement was used to determine what the correct output should be.

Instead of using the else if() for each condition, we would split each condition separately and nest the conditional statements instead:

class IfElseIf {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int grade = 85;

if(grade > 90) {

System.out.println("You got an A");

}

else {

if(grade > 80) {

System.out.println("You got a B");

}

else {

if(grade > 70) {

System.out.println("You got a C");

}

else {

if(grade > 60) {

System.out.println("You got a D");

}

else {

if(grade <= 60) {

System.out.println("You got a F");

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

While the results are the same (a grade of B), the structure of the logic is slightly different. It must be said, though, that this approach is not common in the world of Java programming.

Nested Selection Statement

A selection statement that appears in one of the branches of another conditional statement.

Nested selection statements are extremely useful when there are multiple variables that are being tracked for various criteria.

Consider the following example with multiple variables based on two different conditions. The first condition is whether or not we are hungry and the second condition is whether we want a healthy meal.

The conditions may look like the following, as a starting point:

class Hungry {

public static void main(String[] args) {

char hungry = 'y';

char healthy = 'y';

if(hungry == 'n' && healthy == 'n') {

System.out.println("Not hungry.");

}

else if(hungry == 'n' && healthy == 'y') {

System.out.println("Not hungry.");

}

else if(hungry == 'y' && healthy == 'n') {

System.out.println("Getting some junk food.");

}

else if(hungry == 'y' && healthy == 'y') {

System.out.println("Getting a healthy meal.");

}

}

}

This can seem a bit complex, and the results may look like a truth table. When converting this information into a nested conditional, the outer if() statement is based on whether or not we are hungry criteria, and the inner condition is based on if we want to have a healthy meal or not. Each inner condition is entered only if the outer condition is satisfied, so if we are not hungry, the inner condition is never tested.

When the inner condition is entered if the outer condition is satisfied:

class Hungry {

public static void main(String[] args) {

char hungry = 'y';

char healthy = 'y';

if(hungry == 'n') {

if(healthy == 'n') {

System.out.println("Not hungry.");

}

else {

System.out.println("Not hungry.");

}

}

else {

if(healthy == 'n') {

System.out.println("Getting some junk food.");

}

else {

System.out.println("Getting a healthy meal.");

}

}

}

}

What if we’re not hungry? If we’re not hungry, the check on the healthy meal isn’t necessary because the output is the same. This is the same as a short-circuit evaluation of the criteria if the hungry variable is set to 'n'. Instead of using the short-circuit method, you can simply combine the criteria together.

Consider the following code that combines criteria together:

class Hungry {

public static void main(String[] args) {

char hungry = 'y';

char healthy = 'y';

if(hungry == 'n') {

System.out.println("Not hungry.");

}

else {

if(healthy == 'n') {

System.out.println("Getting some junk food.");

}

else {

System.out.println("Getting a healthy meal.");

}

}

}

}

Visually, this makes it much easier to follow than the chained conditional statement. We could also make a change to get the user’s input in choosing the answers:

import java.util.Scanner;

class Hungry {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Scanner input = new Scanner(System.in);

char hungry;

char healthy;

System.out.print("Are you hungry? (y/n): ");

String response = input.nextLine();

hungry = response.charAt(0);

System.out.print("Do you want a healthy meal? (y/n): ");

response = input.nextLine();

healthy = response.charAt(0);

if(hungry == 'n' || hungry == 'N') {

System.out.println("Not hungry.");

}

else {

if(healthy == 'n' || healthy == 'N') {

System.out.println("Getting some junk food.");

}

else {

System.out.println("Getting a healthy meal.");

}

}

}

}

Unfortunately, this instance is partially flawed. It would not make sense to ask the user what they want to eat if they are not hungry. This could be changed around to prompt the user at each junction, but only prompt the user about what type of meal they want if they selected that they were hungry. To do that, the user would be prompted to see if they were hungry first. Then, within the else() condition, if the user is hungry, they can be prompted to respond if they want a healthy meal or not. There’s no point asking the user if they want a healthy meal or not if they aren’t hungry.

Let’s see what the code would look like with that change:

import java.util.Scanner;

class Hungry {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Scanner input = new Scanner(System.in);

char hungry;

char healthy;

System.out.print("Are you hungry? (y/n): ");

String response = input.nextLine();

hungry = response.charAt(0);

if(hungry == 'n' || hungry == 'N') {

System.out.println("Not hungry.");

}

else {

System.out.print("Do you want a healthy meal? (y/n): ");

response = input.nextLine();

healthy = response.charAt(0);

if(healthy == 'n' || healthy == 'N') {

System.out.println("Getting some junk food.");

}

else {

System.out.println("Getting a healthy meal.");

}

}

}

}

This approach works a lot better. It is an example that couldn’t be performed in a chained conditional statement, as you can nest multiple different criteria and conditions in each case.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) “JAVA, JAVA, JAVA: OBJECT-ORIENTED PROBLEM SOLVING, THIRD EDITION” BY R. MORELLI AND R. WALDE. ACCESS FOR FREE AT CS.TRINCOLL.EDU/~RAM/JJJ/JJJ-OS-20170625.PDF. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL. (2) “PYTHON FOR EVERYBODY” BY DR. CHARLES R. SEVERANCE. ACCESS FOR FREE AT PY4E.COM/HTML3/. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 3.0 UNPORTED.