Table of Contents |

The Mughal Empire was founded by Babur in 1526 and met its end in 1757, although its influence lasted well into the 19th century. The artwork that you will see today comes from Delhi, India.

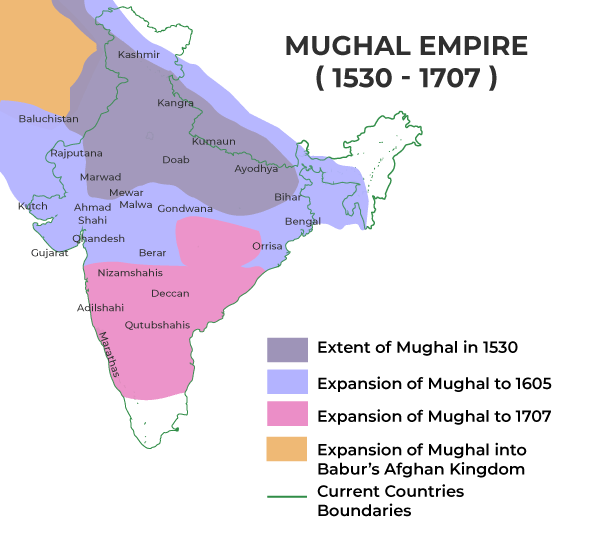

The map below shows the extent of the Mughal Empire and how it expanded in terms of territory and cultural influence over 2 centuries.

The conqueror Zahir-ud-din Muhammad Babur, known more commonly as Babur, originated from central Asia.

Babur Relaxing While Being Entertained

Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin

1605

Painting; Book/manuscript/album; Watercolor, Opaque watercolor, gold, and ink on paper

Babur, a Muslim ruler who was originally from modern-day Uzbekistan, embarked on a series of military campaigns that led to the establishment of an empire. After securing territories in modern-day Afghanistan, Babur set his sights on the Delhi Sultanate in northern India. His decisive victory at the Battle of Panipat in 1526 marked a major turning point. This triumph allowed Babur to establish himself as the ruler of Delhi and found what would become the Mughal Empire. This empire profoundly influenced the region’s history, culture, and architecture for centuries.

The miniature form was popular for creating works of Islamic art in Mughal India. It was almost exclusively the primary form of artwork in which the use of human images was permitted or even commonplace. A majority of other Islamic works are aniconic in that they do not show human or animal forms.

The Persian influence is distinctly evident in Mughal art, reflecting a tradition that never completely forbade the depiction of human figures, provided they were rendered in small, detailed images, typically the size of a textbook page. Persian artists were often invited to the Mughal court to teach and create art.

Common miniature subjects included royal portraits, historical events, literary works, and nature. Artists used fine brushes made from squirrel hair to achieve delicate details. The paintings were often done on paper or ivory and used vibrant colors derived from minerals, vegetables, and precious stones.

Usually kept in a book and only shown to select individuals, miniatures would have rarely been displayed on walls. The private nature of miniatures meant that fewer rules were imposed on their imagery in comparison to other religious art and architecture. The exception, of course, was the universal prohibition within all Islamic art of showing the Prophet Muhammad or Allah.

A popular subject matter for miniatures was well-known historical or religious stories, such as this miniature entitled Akbar and the Elephant Hawa’i.

Akbar and the Elephant Hawa’i

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

1590–1595

Watercolor and gold on paper

This miniature painting depicts the third Mughal ruler and a great patron of the arts, Akbar the Great, bringing a runaway elephant named Hawa’i under control. It serves as an allegory for Akbar’s effective and skillful governance. This artwork is rich in symbolism and carries several layers of meaning, reflecting the emperor’s authority, bravery, and leadership qualities.

Such miniatures served as visual records of significant events and achievements, helping to perpetuate the legacy of the Mughal rulers. The stories and allegories depicted in artworks such as Akbar and the Elephant Hawa’i inspired loyalty and respect among the subjects, reinforcing the ruler’s image as a heroic and capable leader.

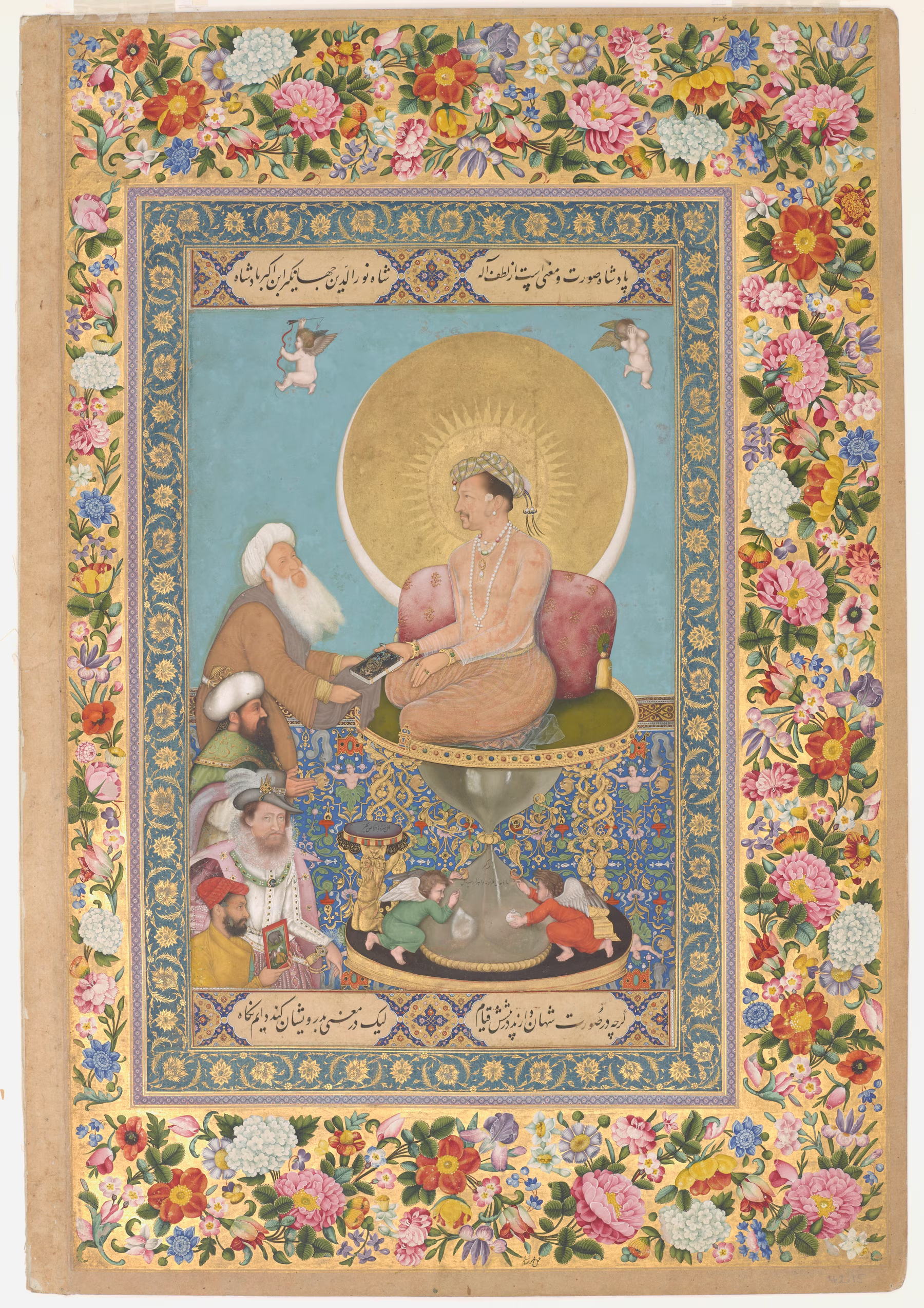

The Mughal Empire was a cultural melting pot, engaging in extensive interactions with various other civilizations, including those of western and northern Europe. This exchange of ideas and artistic techniques is vividly illustrated in the allegorical painting titled Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaykh to Kings. This painting reflects the synthesis of Mughal and European artistic traditions, highlighting the cosmopolitan nature of the Mughal court.

Jahangir, known for his patronage of the arts, continued the legacy of his father, Akbar, in fostering a culturally vibrant and artistically innovative court. His reign was marked by significant artistic achievements and the flourishing of miniature paintings.

The figure at the bottom, wearing a red turban, is a self-portrait of the artist, Bichitr. Including himself in the painting, Bichitr acknowledges his role in creating this artwork and subtly emphasizes the significance of the artist in documenting and interpreting imperial power. By placing himself in the painting, Bichitr also illustrates the close relationship between the artist and the patron as well as the high regard in which artists were held at the Mughal court.

Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaykh to Kings

Smithsonian Museums

1615–1618

Watercolor, gold, and ink on paper

The vertical arrangement of the figures suggests a hierarchy of values. The artist, European monarch, and Turkish sultan represent earthly powers and cultural connections, while the Sufi saint represents divine wisdom and spiritual authority. Jahangir’s act of receiving the book from the Sufi saint signifies his prioritization of spiritual over worldly matters.

The painting serves as an allegory for Jahangir’s ideal leadership, portraying him as a ruler who seeks divine wisdom and spiritual guidance and reinforcing his legitimacy and moral authority as an emperor.

The inclusion of diverse figures highlights the Mughal court’s cosmopolitan nature and its engagement with various cultures and political entities. It showcases the blend of Eastern and Western influences that characterized the Mughal period.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY IAN MCCONNELL AND TAMORA KOWALSKI FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.