Table of Contents |

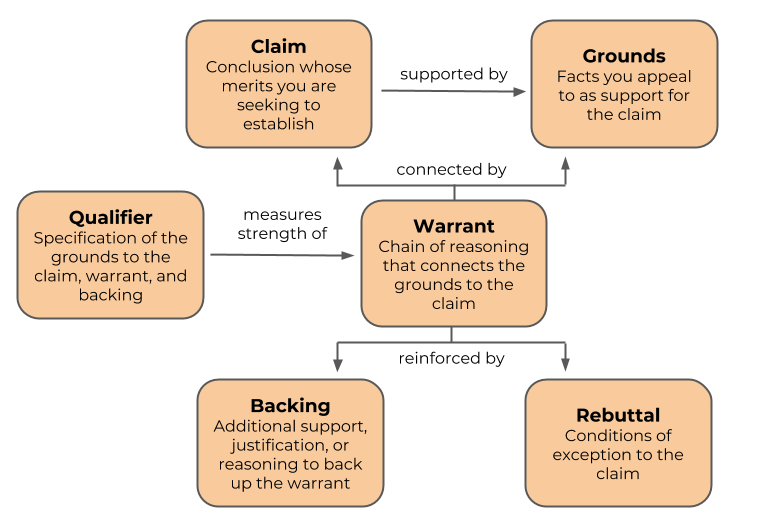

Stephen Toulmin, an English philosopher and logician, identified six elements of a persuasive argument.

In the Toulmin argument model, these elements become useful categories by which an argument may be analyzed:

A claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept. This can include both information you want someone to accept and actions you want someone to take.

EXAMPLE

You should use a hearing aid.Many writers start with a claim but then find that it is challenged. If you just ask people to do something, they may not simply agree with what you want. They will likely ask why they should agree with you. In other words, they will ask you to prove your claim. This is where grounds become important.

The grounds is the basis of real persuasion and is made up of data and hard facts, plus the reasoning behind the claim. It is the "truth" on which the claim is based. Grounds may also include proof of expertise and the basic premises on which the rest of the argument is built.

The actual truth of the data may be less than 100%, as much data are ultimately based on perception. We assume what we measure is true, but there may be problems in this measurement, ranging from a faulty measurement instrument to biased sampling.

It is critical to the argument that the grounds are not challenged because, if they are, they may become a claim which you will need to prove with even deeper information and further argument.

EXAMPLE

Over 70% of all people over age 65 have a hearing difficulty.Information is usually a very powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are logical or rational are more likely to be persuaded by factual data, while those who argue emotionally and are highly invested in their own position will challenge that data or otherwise try to ignore it.

It is often a useful test to give something factual to the other person that disproves their argument, and watch how they handle it. Some will accept it without question. Some will dismiss it out of hand. Others will dig deeper, requiring more explanation. This is where the warrant comes into play.

A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be explicit or unspoken and implicit. Either way, it answers the question, "Why does that data mean your claim is true?"

EXAMPLE

A hearing aid helps most people to hear better.Warrants may be based on the rhetorical appeals of logos, ethos, or pathos, or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener.

In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and hence unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant by answering different questions.

EXAMPLE

Hearing aids are available locally.The qualifier indicates the strength of the leap from the data to the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies.

It includes words such as "most," "usually," or "sometimes." Arguments may thus range from strong assertions to flimsy, vague statements.

EXAMPLE

Hearing aids help most people.Another variant is the reservation, which allows for the possibility that the claim is incorrect.

EXAMPLE

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.Qualifiers and reservations are frequently used by advertisers who are prohibited from lying; they slip words like "usually," "virtually," and "unless" into their claims.

Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be addressed either through a continued dialogue or by preempting the counterargument by giving a rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument.

EXAMPLE

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.Any rebuttal is an argument in itself and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and so on. It can also have its own rebuttal. Thus if you are presenting an argument, you can seek to understand possible rebuttals as well as rebuttals to those rebuttals.

The Rogerian argument model, inspired by the influential psychologist Carl Rogers, aims to find compromise on a controversial issue.

If you are using the Rogerian approach, your introduction to the argument should accomplish three objectives:

The following is an example of how the introduction of a Rogerian argument can be written. The topic in this case is racial profiling.

In Dwight Okita’s “In Response to Executive Order 9066,” the narrator—a young Japanese-American—writes a letter to the government, who has ordered her family into a relocation camp after Pearl Harbor. In the letter, the narrator details the people in her life, from her father to her best friend at school. Since the narrator is of Japanese descent, her best friend accuses her of “trying to start a war” (18). The narrator is seemingly too naïve to realize the ignorance of this statement and tells the government that she asked this friend to plant tomato seeds in her honor. Though Okita’s poem deals specifically with World War II, the issue of race relations during wartime is still relevant. Recently, with the outbreaks of terrorism in the United States, Spain, and England, many are calling for racial profiling to stifle terrorism. The issue has sparked debate, with one side calling it racism and the other calling it common sense.

Once you have written your introduction, you must show the two sides to the debate you are addressing. Though there are always more than two sides to a debate, Rogerian arguments choose two to put in stark opposition to one another.

Summarize each side, then provide a middle path. Your summary of the two sides will be your first two body paragraphs. Use quotations from outside sources to effectively illustrate the position of each side.

An outline for a Rogerian argument might look like this:

Since the goal of a Rogerian argument is to find a common ground between two opposing positions, you must identify the shared beliefs or assumptions of each side and try to find a workable solution.

EXAMPLE

In the racial profiling example above, both sides desire a safer society. Therefore, a better solution would maybe focus on more objective measures than race; this could involve something like the use of more screening technology on public transportation.Once you have a claim that disarms the central dispute, you should support the claim with evidence and quotations when appropriate.

In a Rogerian argument, your conclusion should:

Though the debate over racial profiling is sure to continue, each side desires to make the United States a safer place. With that goal in mind, our society deserves better security measures than merely searching people of a certain race. We cannot waste time with such subjective matters, especially when we have technology that could more effectively locate potential terrorists. Sure, installing metal detectors and cameras on public transportation is costly, but feeling safe in public is priceless.

Source: This content has been adapted from Lumen Learning's "Rogerian Argument" and "Toulmin's Argument Model" tutorials.