Table of Contents |

Most cells in the body make use of charged particles, ions, to build up a charge across the cell membrane. Recall that this was shown to be a part of how muscle cells work. For skeletal muscles to contract, based on excitation–contraction coupling, input from a neuron is required. Both of the cells make use of the cell membrane to regulate ion movement between the extracellular fluid and cytosol.

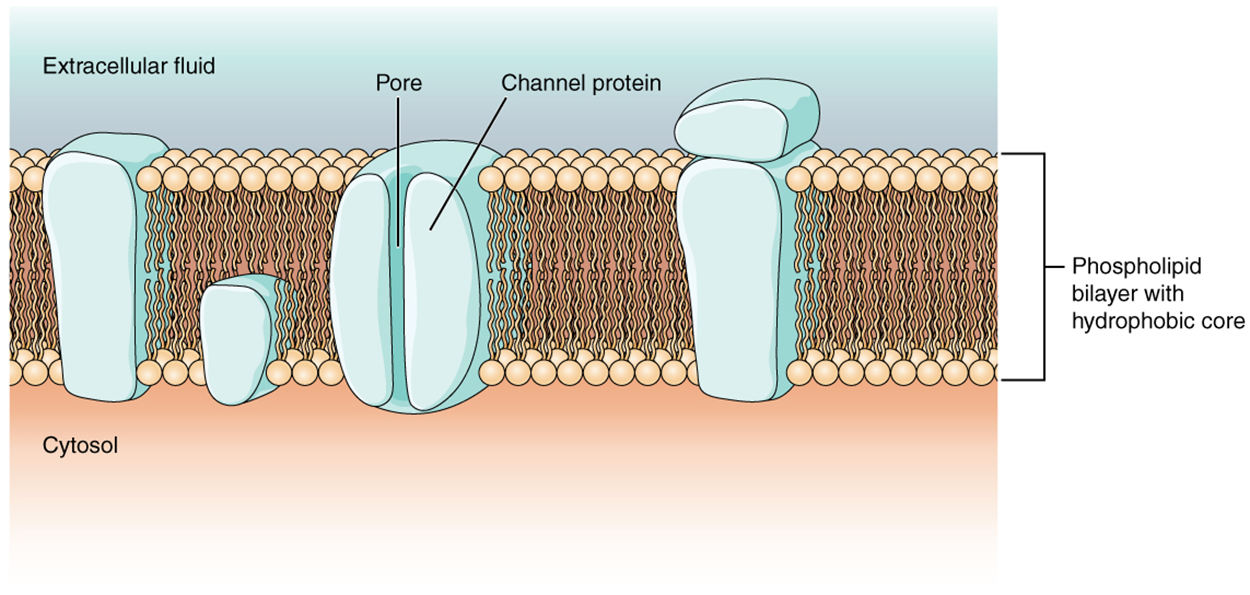

Also, recall that the cell membrane is primarily responsible for regulating what can cross the membrane and what stays on only one side. The cell membrane is a phospholipid bilayer, so only substances that can pass directly through the hydrophobic core can diffuse through unaided. Charged particles, which are hydrophilic by definition, cannot pass through the cell membrane without assistance. Transmembrane proteins, specifically channel proteins, make this possible. Several passive transport channels, as well as active transport pumps, are necessary to generate a transmembrane potential and an electrochemical signal. Of special interest is the carrier protein referred to as the sodium–potassium pump that moves sodium ions (Na⁺) out of a cell and potassium ions (K⁺) into a cell, thus regulating ion concentration on both sides of the cell membrane.

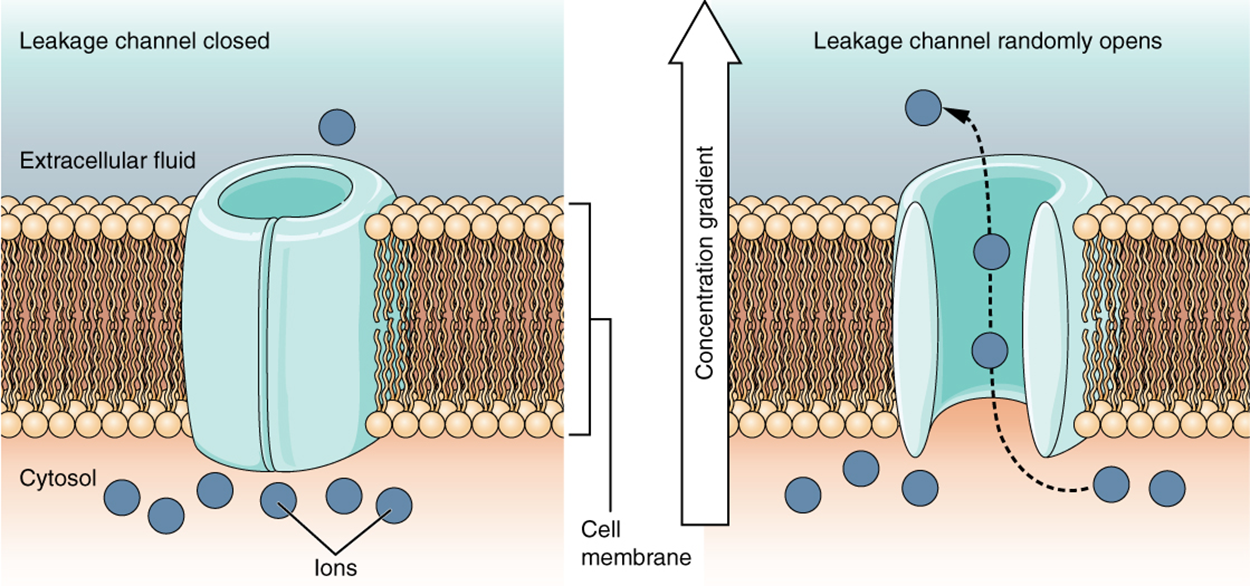

Ion channels are pores that allow specific charged particles to cross the membrane in response to an existing concentration gradient. Each ion channel is a protein formed by a unique sequence of amino acids. The amino acids that are present along the pore and the size of the pore will determine the type of ion that channel allows through. Channels for cations (positive ions) will have negatively charged side chains in the pore. Channels for anions (negative ions) will have positively charged side chains in the pore. Smaller pores cannot allow larger ions through, while larger pores do not allow smaller ions (associated with water) through. Some ion channels are selective for charge but not necessarily for size, and thus are called a nonspecific ion channel.

Ion channels do not always freely allow ions to diffuse across the membrane. Some are opened by certain events, meaning the channels are gated. So, another way that channels can be categorized is on the basis of how they are gated. Although these classes of ion channels are found primarily in the cells of nervous or muscular tissue, they also can be found in the cells of epithelial and connective tissues.

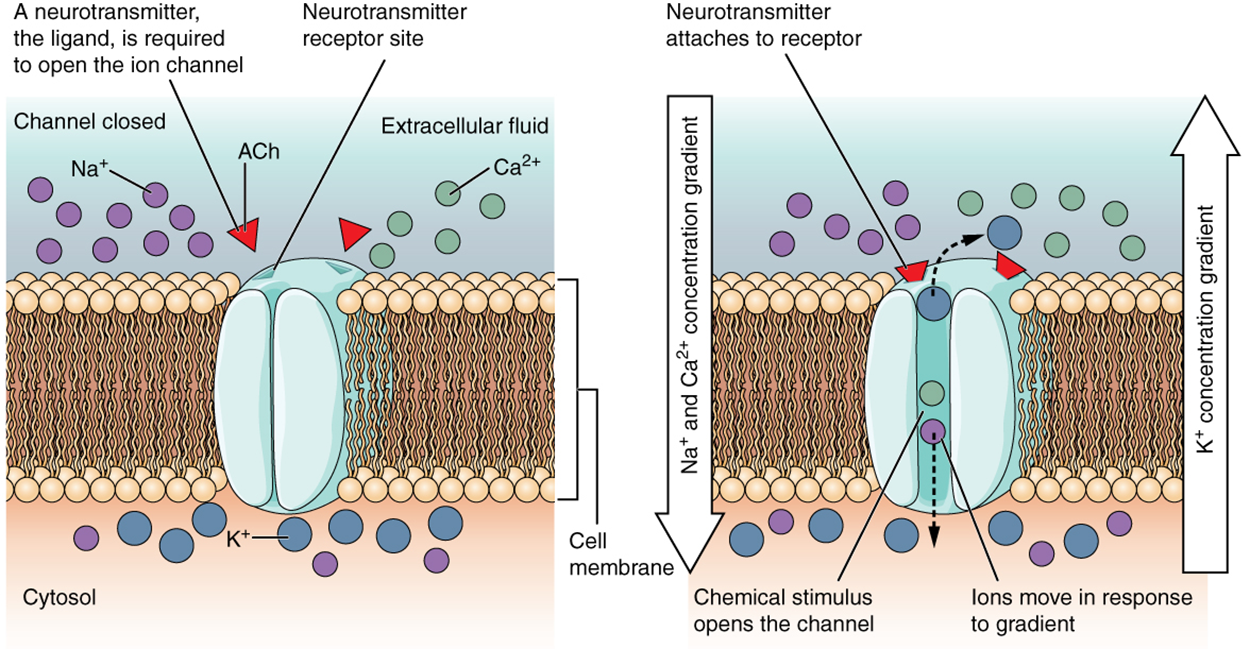

A ligand-gated channel, also known as a chemically gated channel, opens because a signaling molecule, a ligand (chemical), binds to the extracellular region of the channel.

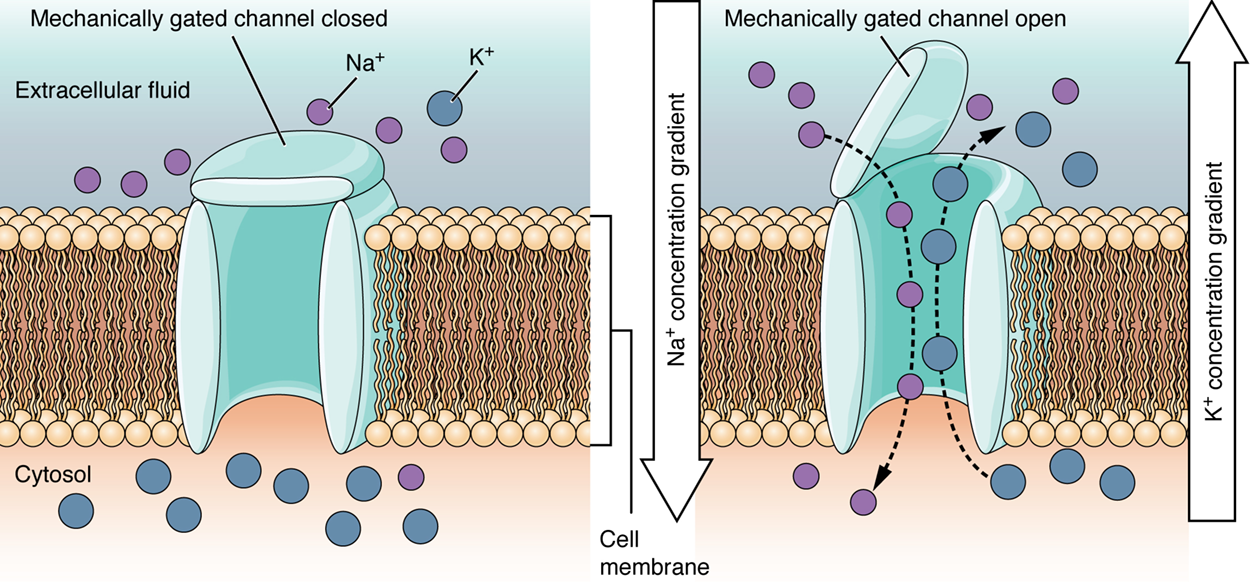

A mechanically gated channel opens because of a physical distortion of the cell membrane. Many channels associated with the sense of touch are mechanically gated. For example, as pressure is applied to the skin, these channels open and allow ions to enter the cell.

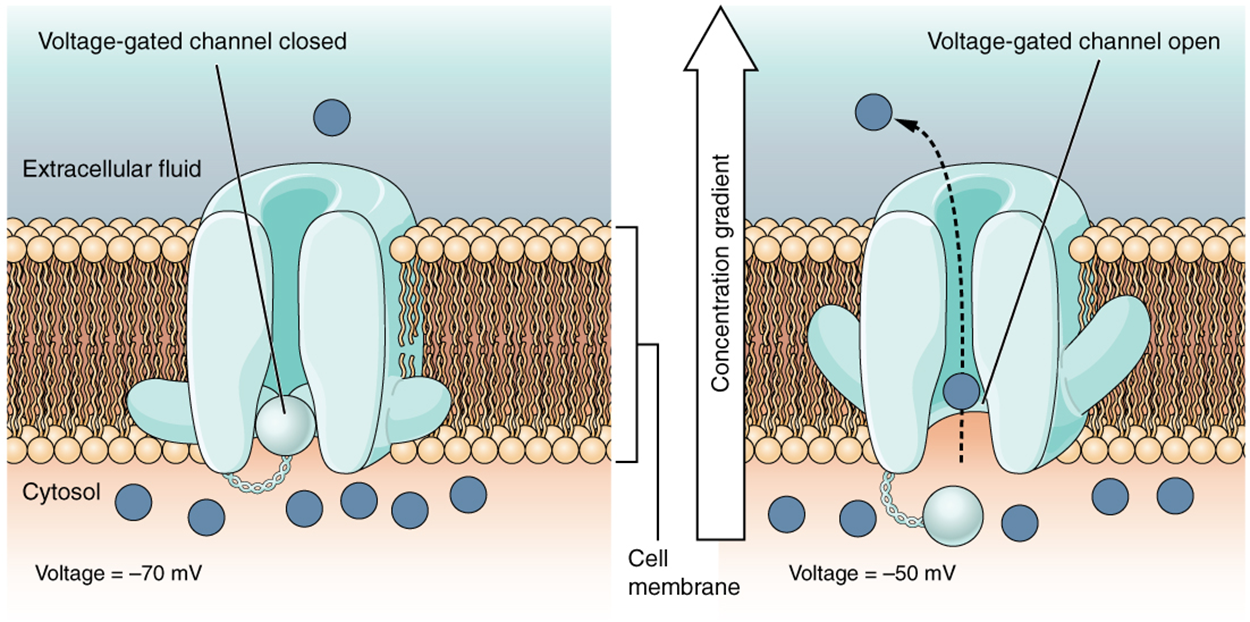

A voltage-gated channel is a channel that responds to changes in the electrical properties of the membrane in which it is embedded. Normally, the inner portion of the membrane is at a negative voltage. When that voltage becomes less negative, the channel begins to allow ions to cross the membrane.

A leakage channel is randomly gated, meaning that it opens and closes at random, hence the reference to leaking. There is no actual event that opens the channel; instead, it has an intrinsic rate of switching between the open and closed states. Leakage channels are important because they keep the neuron primed and ready to go by helping maintain resting membrane potential.

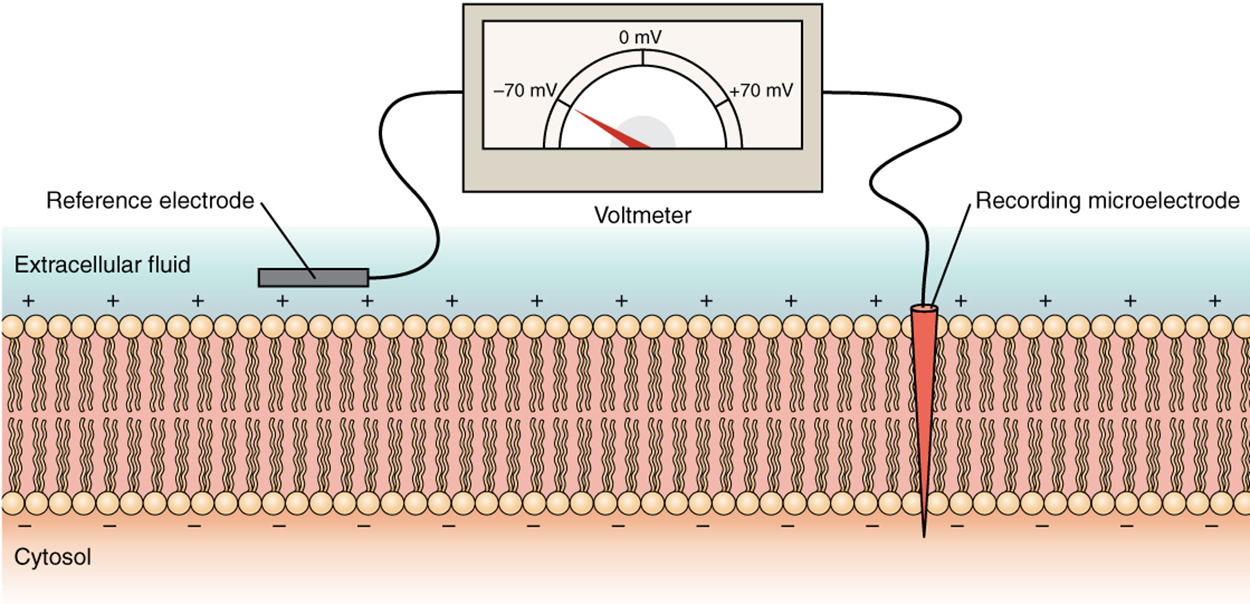

The electrical state of the cell membrane can have several variations. These are all variations in the membrane potential. Recall that a membrane potential is a difference in electrical charge across a cell membrane. This charge is based on a differential distribution of charge across the cell membrane, measured in millivolts (mV). The standard is to compare the inside of the cell relative to the outside, so the membrane potential is a value representing the charge on the intracellular side of the membrane based on the outside being zero, relatively speaking. As shown in the image below, there is an overall positive charge on the outside of the cell membrane and an overall negative charge on the inside. Therefore, the membrane potential (inside relative to outside) is negative. If the indicated charges were swapped (outside was negative, and inside was positive), then the membrane potential would be positive.

The concentration of ions in extracellular and intracellular fluids is largely balanced, with a net neutral charge. However, a slight difference in charge occurs right at the membrane surface, both internally and externally. It is the difference in this very limited region that has all the power in neurons (and muscle cells) to generate electrical signals.

With the ions distributed across the membrane at these concentrations, the difference in charge during steady-state conditions is described as the resting membrane potential. The exact value measured for the resting membrane potential varies between cells; −70 mV is the most commonly used value for neurons (skeletal muscle cells are −85 mV).

A neuron can receive input from other neurons and, if this input is strong enough, send the signal to downstream neurons. Transmission of a signal between neurons is generally carried by a chemical called a neurotransmitter. Transmission of a signal within a neuron (from dendrite to axon terminal) is carried by a brief reversal of the resting membrane potential called an action potential.

A neurotransmitter is a chemical signal that is released from the synaptic end bulb of a neuron to cause a change in the target cell. When neurotransmitter molecules bind to receptors located on a neuron’s dendrites, ion channels open.

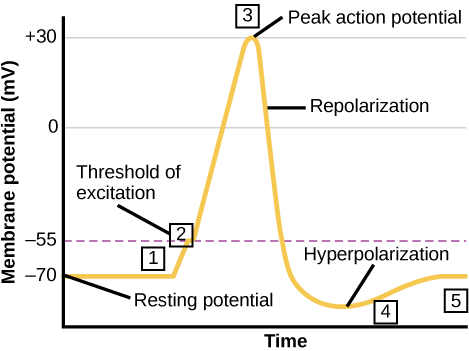

At excitatory synapses, this opening allows positive ions to enter the neuron and results in depolarization of the membrane—a decrease in the difference in voltage between the inside and outside of the neuron. A stimulus from a sensory cell or another neuron depolarizes the target neuron to its threshold potential (−55 mV). Na⁺ channels in the axon hillock open, allowing positive ions to enter the cell. Once the sodium channels open, the neuron completely depolarizes to a membrane potential of about +40 mV. Action potentials are considered an "all-or-nothing" event, in that once the threshold potential is reached, the neuron always completely depolarizes.

Once depolarization is complete, the cell must now "reset" its membrane voltage back to the resting potential. To accomplish this, the Na⁺ channels close and cannot be opened. This begins the neuron's refractory period, in which it cannot produce another action potential because its sodium channels will not open. At the same time, voltage-gated K+ channels open, allowing K⁺ to leave the cell. As K⁺ ions leave the cell, the membrane potential once again becomes negative and repolarizes.

The diffusion of K⁺ out of the cell actually continues for a short period of time past the time of the achievement of the resting potential, and the membrane hyperpolarizes, in that the membrane potential becomes more negative than the cell's normal resting potential. This is the result of the slow closing of the K⁺ channels. At this point, the sodium channels will return to their resting state, meaning they are ready to open again if the membrane potential again exceeds the threshold potential. Eventually, all the K⁺ channels close, and the cell returns back to its resting membrane potential.

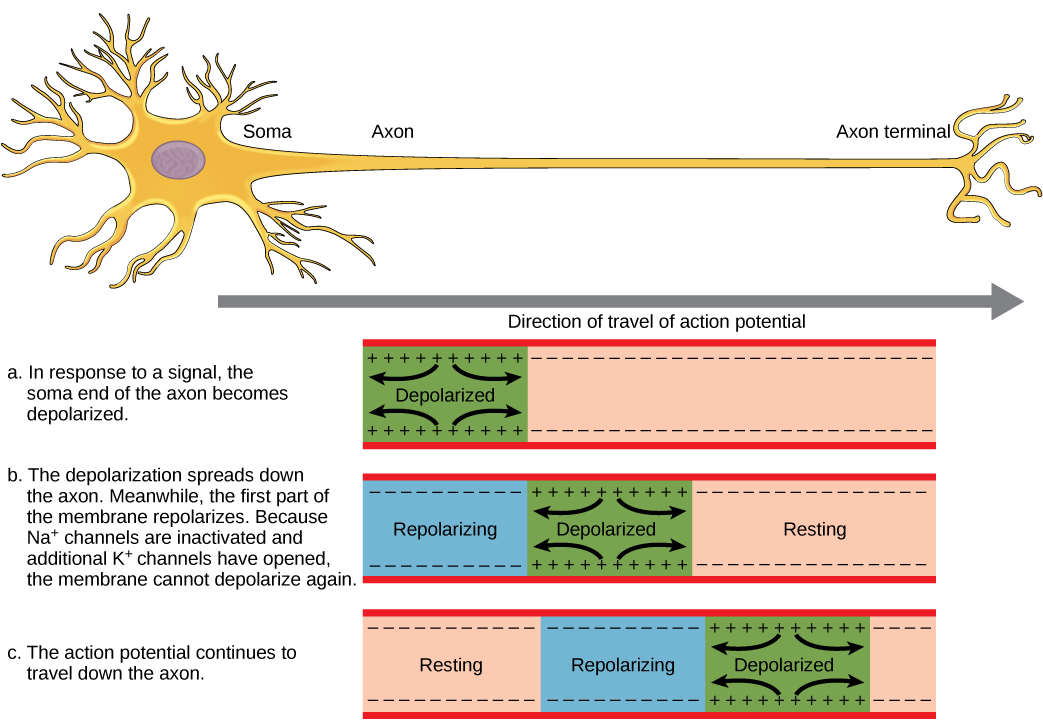

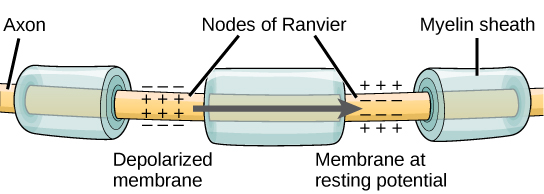

For an action potential to communicate information to another neuron, it must travel along the axon and reach the axon terminals where it can initiate neurotransmitter release. The speed of conduction of an action potential along an axon is influenced by both the diameter of the axon and the axon’s resistance to current leak. Recall that myelin acts as an insulator that prevents current from leaving the axon; this increases the speed of action potential conduction. In demyelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis, action potential conduction slows because current leaks from previously insulated axon areas.

You previously learned that the nodes of Ranvier are gaps in the myelin sheath along the axon. These unmyelinated spaces are about one micrometer long and contain voltage-gated Na⁺ and K⁺ channels. Flow of ions through these channels, particularly the Na⁺ channels, regenerates the action potential over and over again along the axon. This “jumping” of the action potential from one node to the next is called saltatory propagation.

If nodes of Ranvier were not present along an axon, the action potential would propagate very slowly because Na⁺ and K⁺ channels would have to continuously regenerate action potentials at every point along the axon instead of at specific points. Nodes of Ranvier also save energy for the neuron since the channels only need to be present at the nodes and not along the entire axon.

Continuous propagation occurs along unmyelinated axons. This process is slower than saltatory propagation because the voltage-gated Na⁺ channels are located along the entire axon.

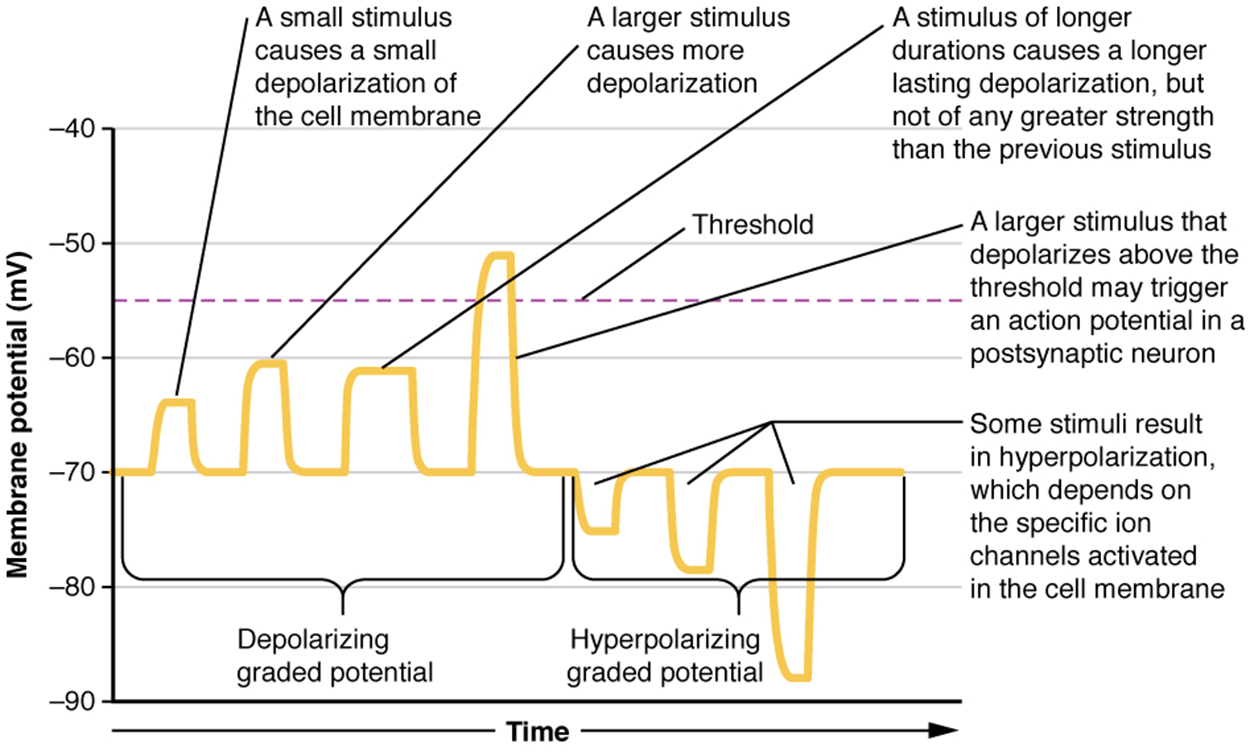

Local changes in the membrane potential are called graded potentials and are usually associated with the dendrites of a neuron. The amount of change in the membrane potential is determined by the size of the stimulus that causes it.

EXAMPLE

Testing the temperature of the shower, slightly warm water would only initiate a small change in a heat-sensitive receptor, whereas hot water would cause a large amount of change in the membrane potential.Graded potentials can be of two sorts:

Depolarizing graded potentials are often the result of Na⁺ or Ca²⁺ entering the cell. Both of these ions have higher concentrations outside the cell than inside; because they have a positive charge, they will move into the cell, causing it to become less negative relative to the outside.

Hyperpolarizing graded potentials can be caused by K⁺ leaving the cell or Cl⁻ entering the cell. If a positive charge moves out of a cell, the cell becomes more negative; if a negative charge enters the cell, the same thing happens.

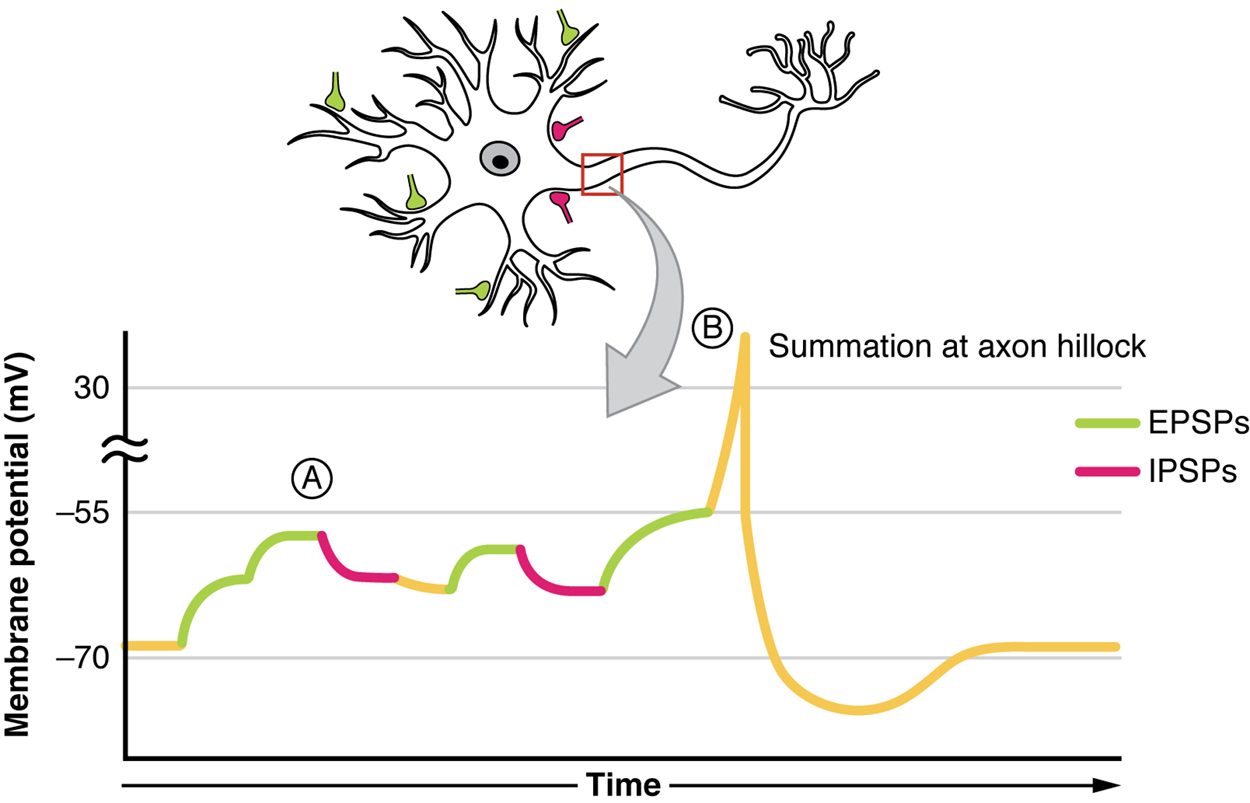

A postsynaptic potential (PSP) is the graded potential in the dendrites of a neuron that is receiving synapses from other cells. Postsynaptic potentials can be depolarizing or hyperpolarizing.

Depolarization in a postsynaptic potential is called an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) because it causes the membrane potential to move toward threshold.

Hyperpolarization in a postsynaptic potential is an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) because it causes the membrane potential to move away from threshold.

All types of graded potentials will result in small changes of either depolarization or hyperpolarization in the voltage of a membrane. These changes can lead to the neuron reaching threshold if the changes add together, or summate. The combined effects of different types of graded potentials are illustrated in the image below. If the total change in voltage in the membrane is a positive 15 mV, meaning that the membrane depolarizes from −70 mV to −55 mV, then the graded potentials will result in the membrane reaching threshold.

Graded potentials summate at a specific location at the beginning of the axon to initiate the action potential, namely the initial segment. This location has a high density of voltage-gated Na⁺ channels that initiate the depolarizing phase of the action potential.

Summation can be spatial or temporal, meaning it can be the result of multiple graded potentials at different locations on the neuron, or all at the same place but separated in time. Spatial summation is the combination of various inputs to a neuron with each other. Temporal summation is the combination of multiple action potentials from a single cell resulting in a significant change in the membrane potential. Spatial and temporal summation can act together as well.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.