Table of Contents |

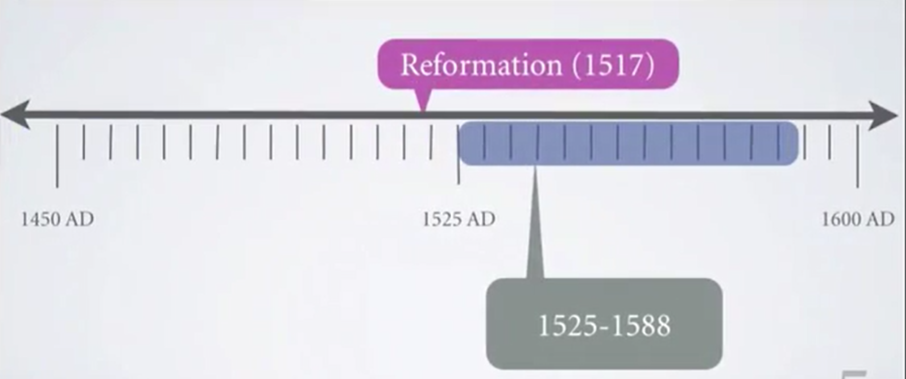

The artwork that you will be looking at today dates from between 1525 and 1588. In the timeline below, the beginning of the Protestant Reformation in 1517 is noted as a reference point. These works of art come from Italy and Spain, specifically the city of Toledo.

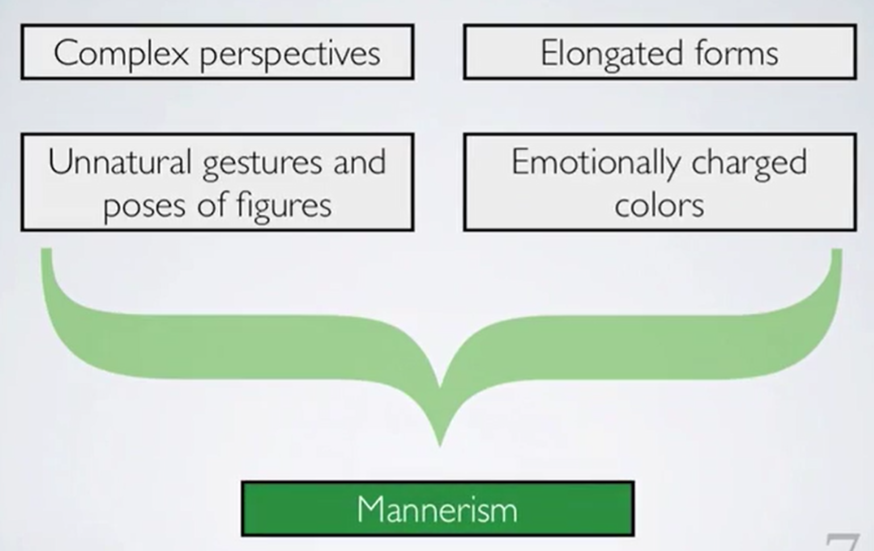

Mannerism is considered a response to the Renaissance style that dominated Italy during this period. Mannerism is characterized by:

Whereas the Renaissance artists—in their efforts to make paintings as realistic as possible—attempted to conceal the construction of the artwork, Mannerists embraced it, and in a sense, created a characterization of the Renaissance style.

This first artist, known as Jacopo da Pontormo, was a Mannerist painter who originated from the region of Florence. Here is his self-portrait:

1494-1557

Florence, Italy

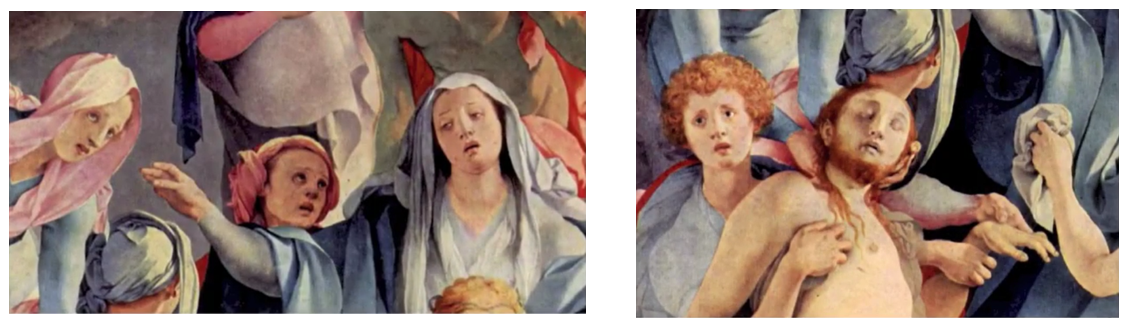

One of Pontormo’s most important paintings is that of the descent, shown below. “Descent from the Cross” is also known as “The Entombment of Christ,” as it has remained unclear which scene is being depicted, given that Pontormo opted not to include any objects in his painting.

1525-1528

Oil on panel

One of the first things you notice is the use of emotionally charged colors. Pontormo chose a palette of mostly pastels with pink and blue dominating the image. The empty space in the middle, detailed below, is symbolic of grief, and is a departure from other Renaissance artists who tended to concentrate their images near the center of the composition.

Notice how the figures are all blond or reddish haired (below, left) and how Christ is depicted without a mustache (below, right), which is atypical for most depictions of Christ during this period. It’s hard to say for certain whether these attributes were intentional or projections of some of the artist’s own physical traits, but the comparison at least is interesting.

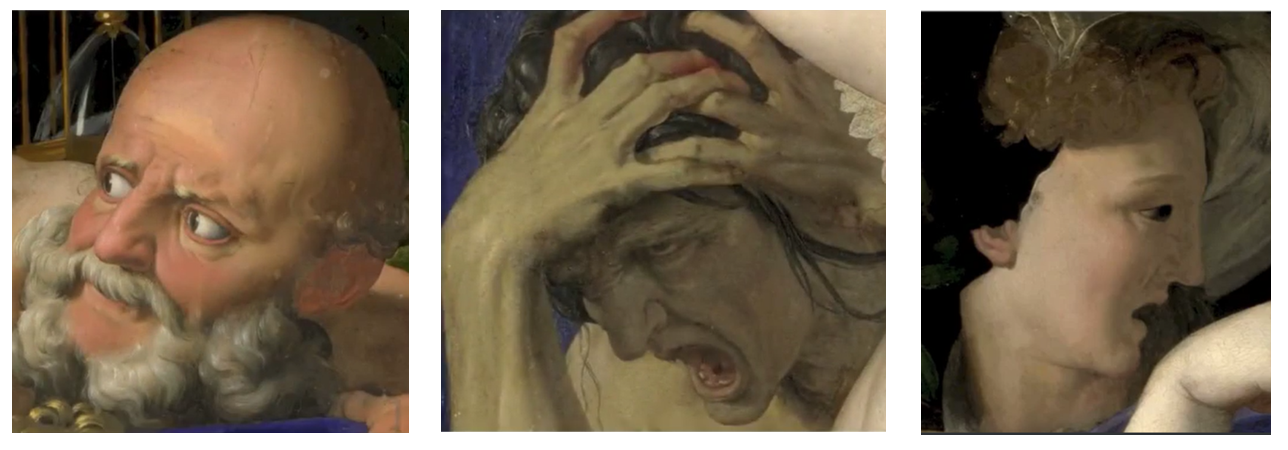

The figures are all shown with varying degrees of concern on their faces, as you can see in the close-up below on the left. On the right, you can see Mary, who is understandably the most visibly upset.

The elongation of forms and uncomfortable or, in some instances, impossible bodily contortions are present as well, and are examples of formal dissonance, meaning what the viewer expects to see conflicts with what is actually shown.

The man born Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola became the Mannerist painter known by his nickname, “Parmigianino,” or “little one from Parma.” As you may have guessed, he worked out of Parma, Italy, among other places. Like Raphael, who died 20 years prior, Parmigianino had a relatively short life, and coincidentally also died at the age of 37. His self-portrait is shown below.

1503-1540

Parma, Italy

His best-known work of art is the “Madonna and Child with Angels,” more familiarly known as the “Madonna with the Long Neck,” which is as apt a nickname as Parmigianino’s own. The exaggerated form of the Virgin Mary emphasizes the delicacy of her feminine features, such as her slender hands, almost swan-like neck, and long legs covered in mounds of beautifully rendered clothing.

1534-1540

Oil on panel

There’s an unsettling sensation that is generated, though, upon closer inspection. Notice the figure in the background with the scroll. He’s included to give some impression of depth to the image and a reference point for the receding background, but his proportions aren’t quite right. Moreover, he appears smaller than he should be. The incomplete capital and background enhance the sensation of formal dissonance—as per Renaissance artwork, a fully rendered background is anticipated, but you don’t get one.

The Virgin Mary is also severely distorted, coming in at nearly nine heads tall, when the natural measure is usually between six and seven. She’s literally gigantic!

Lastly, the baby Jesus would certainly set the record for the longest baby ever. He measures five heads—almost twice the measurement of a typical child at this age, which again reinforces this feeling of formal dissonance. While you might anticipate an intimate scene between mother and child, you are instead treated to a somewhat unnerving scene between an unnatural-looking mother and a gigantic baby.

Agnolo di Cosimo, who generally went by the name Agnolo Bronzino, was a pupil of Pontormo. Here is an image of one of his portraits, although note it is not of the artist himself.

1503-1572

Florence, Italy

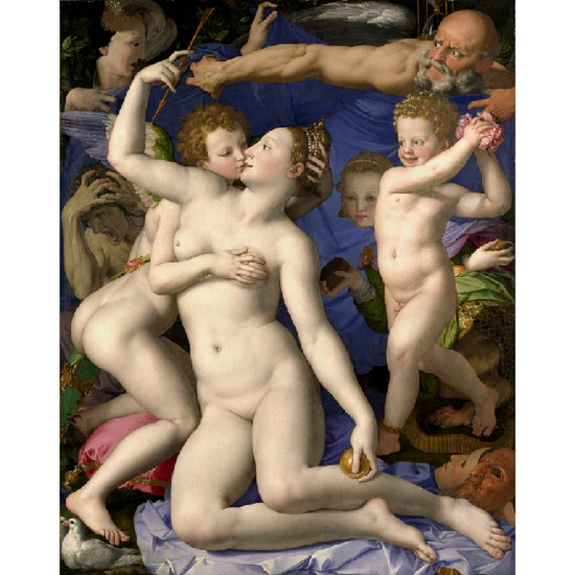

The painting below was commissioned by Cosimo I de’ Medici, ruler of Florence, for the King of France. It is titled “Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time,” and is a somewhat incestuous image centered around the image of Venus being fondled by her child Cupid. In another example of formal dissonance, the childlike head and adult-like body of Cupid don’t seem to match—in fact, the head of Cupid appears to be almost detached from his lower body.

1540-1545

Oil on panel

Folly, the little ruddy-looking boy who looks like he’s poised to hit Venus in the back of the head with rose petals, is beautifully and masterfully painted. It’s an example of just how refined the area of oil painting is becoming during this period. Notice how realistic his curls look.

Below, from left to right, Time appears to be pulling back the curtain, revealing the entire scene to the viewer, and the personification of Fury can be seen in the shadows behind Cupid. Lastly, the masks are symbolic of deceit. It’s difficult to interpret the overall meaning behind the painting, but it is a wonderful example of Bronzino’s application of Mannerist principles.

This last artist, born Doménikos Theotokópoulos but known as El Greco, or “the Greek,” was actually born in Crete—hence his name—but he spent considerable time in Italy before moving to Toledo, Spain, for the remainder of his life. El Greco is known for his blending of Byzantine and Mannerist styles with some Spanish influence, a style uniquely his own. He is also known for the strong emotionalism portrayed through his depictions of forms and use of color. Here is a presumed self-portrait of El Greco (though it is not titled as such):

1541-1614

Crete

This image, called “The Burial of the Count of Orgaz,” is almost bursting with figures crowded into the scene in which the terrestrial and heavenly realms are depicted as almost existing on the same plane. Saints Stephan and Augustine have descended from heaven to lower the count’s body into his grave.

1586-1588

Oil on canvas

There is differentiation, however, in the way the figures are conveyed, and it’s through the use of form. The earthly realm is painted rather realistically, while the elongated figures in heaven are depicted among swirling forms and wispy clouds.

The burial scene is full of black-clad figures in traditional—for the time period—Spanish aristocratic dress. A few of them look upwards in acknowledgment of the heavenly realm, prepared to welcome the soul of the count, who is being lifted upwards by the angel in the center.

Source: This work is adapted from Sophia author Ian McConnell.