Table of Contents |

When people are personally committed to their organization’s plans, those plans are more likely to be accomplished. This truism is the philosophy underlying management by objectives.

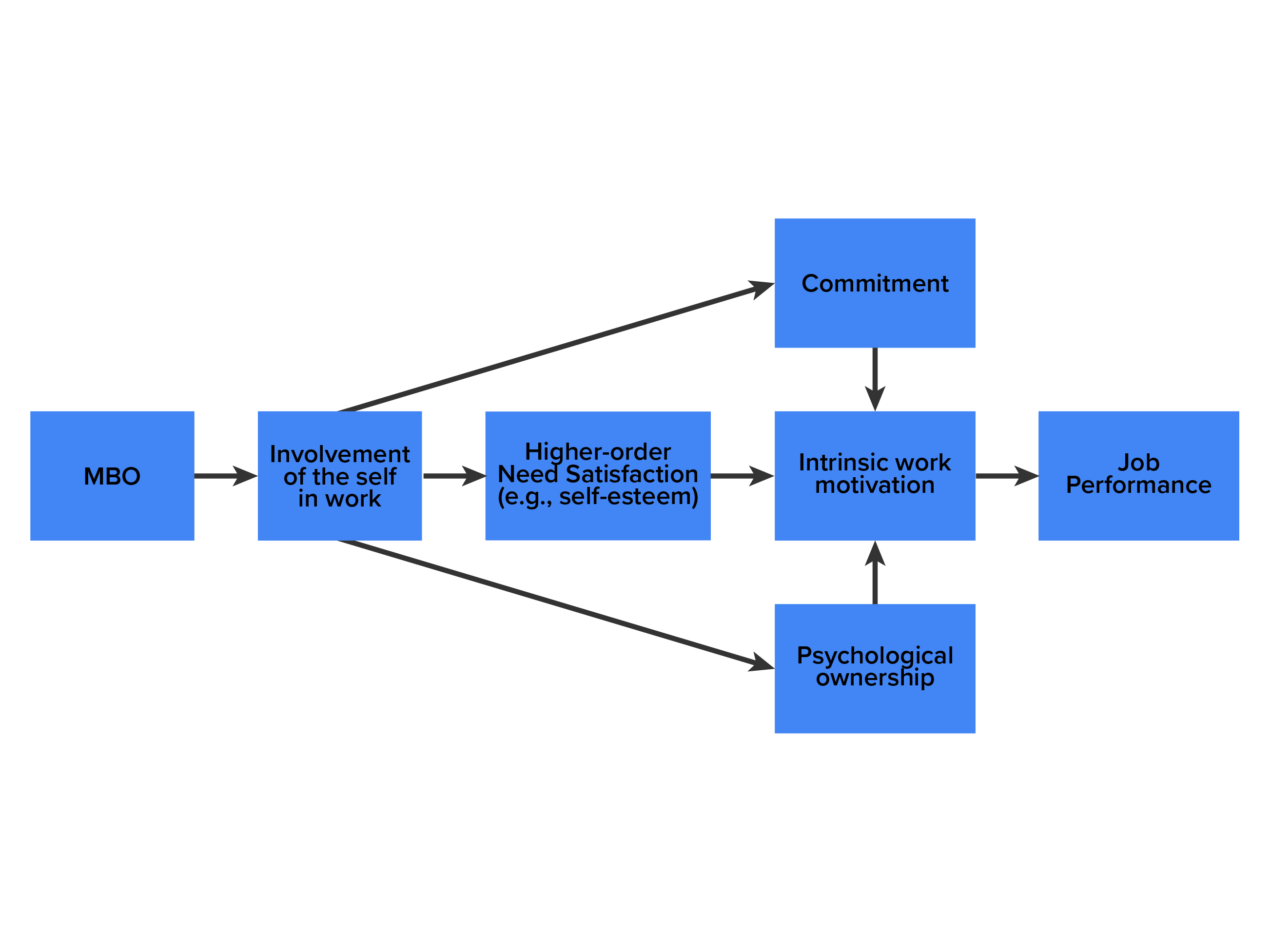

Management by objectives (MBO) is a philosophy of management, a planning and controlling technique, and an employee-involvement program (Drucker & Raia, 1974). As a management philosophy, MBO stems from the human resource model and Theory Y’s assumption that employees are capable of self-direction and self-control. MBO also is anchored in Maslow’s need theory. The reasoning is that employee involvement in the planning and control processes provides opportunities for the employee to immerse the self in work-related activities, to experience work as more meaningful, and to satisfy higher-order needs (such as self-esteem), which leads to increased motivation and job performance (see the diagram below). It is hypothesized that, through involvement, employee commitment to a planned course of action will be enhanced and job satisfaction will be increased.

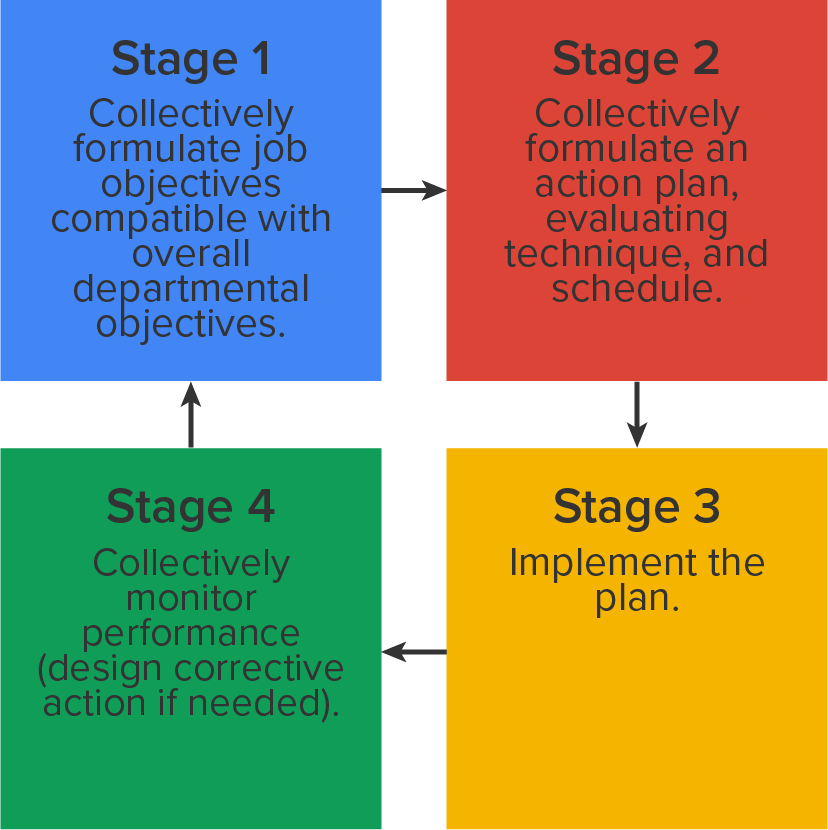

Although there are many variations in the practice of MBO, it is basically a process by which an organization’s goals, plans, and control systems are defined through collaboration between managers and their employees. Together they identify common goals, define the results expected from each individual, and use these measurements to guide the operation of their unit and to assess individual contributions (Odiorne, 1979). In this process, the knowledge and skills of many organizational members are used. Rather than managers telling workers, “These are your goals,”—the approach of classical management philosophy—managers ask workers to join them in deciding what their goals should be.

After an acceptable set of goals has been established for each employee through a give-and-take, collaborative process, employees play a major role in developing an action plan for achieving these goals. In the final stage in the MBO process, employees develop control processes, monitor their own performance, and recommend corrections if unplanned deviations occur. At this stage, the entire process begins again. The following diagram depicts the major stages of the MBO process.

MBO has the potential to enhance organizational effectiveness. The following four major components of the MBO process are believed to contribute to its effectiveness: (1) setting specific goals; (2) setting realistic and acceptable goals; (3) joint participation in goal setting, planning, and controlling; and (4) feedback (Rodgers & Hunter, 1991). First, as we saw earlier, employees working with goals outperform employees working without goals. Second, it is assumed that participation contributes to the setting of realistic goals for which there is likely to be goal acceptance and commitment. Setting realistic and acceptable goals is an important precondition for successful outcomes, especially if the goals are difficult and challenging in nature. Finally, feedback plays an important role. It is only through feedback that employees learn whether they should sustain or redirect their efforts in order to reach their goal, and it is only through feedback that they learn whether or not they are investing sufficient effort.

In the next section, we briefly look at what the research tells us about the effectiveness of MBO programs.

In both the public and private sectors, MBO is a widely employed management tool. A recent review of the research on MBO provides us with a clear and consistent view of the effects of these programs. In the 70 cases studied by Robert Rodgers and John Hunter, 68 showed increased productivity gains, and only 2 showed losses (Rodgers & Hunter, 1991). In addition, the increases in performance were significant. Rodgers and Hunter report that the mean increase exceeded 40 percent.

While the results are generally positive in nature, differences in performance effects appear to be associated with the level of top management commitment. In those cases where top management is emotionally, intellectually, and behaviorally committed to MBO, the performance effects tend to be the strongest. The weakest MBO effects appear when top management does very little to “talk the value/importance of MBO” and they don’t use the system themselves, even as they implement it for others (Hollman, 1976). This evidence tells us that “the processes” used to implement MBO may render a potentially effective program ineffective. Thus, not only should managers pay attention to the strategies used to facilitate planning and controlling (like MBO), they should also be concerned with how they go about implementing the plans. MBO requires top management commitment, and it should be initiated from the top down (Aplin & Schoderbek, 1976).

Research shows that an MBO program can play a meaningful role in achieving commitment to a course of action and improving performance. In fact, research clearly documents instances where MBO programs have increased organizational effectiveness. Still, there have been failures. After reviewing 185 studies of MBO programs, one researcher concluded that they are effective under some circumstances but not all (Kondrasuk, 1981). For example, MBO tends to be more effective in the short term (less than two years), in the private sector, and in organizations removed from direct contact with customers. These factors also affect the success of an MBO program:

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPEN STAX. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Aplin Jr, J. C., & Schoderbek, P. P. (1976). MBO: Requisites for success in the public sector. Human Resource Management, 15(2), 30-36. doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930150206

Drucker, P. F. (1954). The practice of management. Harper & Row.

Greenwood, R. C. (1981). Management by objectives: As developed by Peter Drucker, assisted by Harold Smiddy. Academy of Management Review, 6(2), 225-230. doi.org/10.5465/amr.1981.4287793

Hollmann, R. W. (1976). Applying MBO research to practice. Human Resource Management, 15(4), 28. www.proquest.com/openview/e0aa62f0da6d9b9889ae520c66926443/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=34997

Ivancevich, J. M., Donnelly, J. H., & Gibson, J. M. (1976). Evaluating MBO: The challenge ahead. In J. M. Ivancevich, J. H. Donnelly, & J. M. Gibson (Eds.), Readings in organizations: Behavior, structure, processes (pp. 401-414). Business Publications.

Kondrasuk, J. N. (1981). Studies in MBO effectiveness. Academy of Management Review, 6(3), 419-430. doi.org/10.5465/amr.1981.4285780

Lawler, III, E. E. (1986). High-involvement management. Jossey-Bass.

Lawler, III, E. E. (1992). The ultimate advantage: Creating high involvement organizations. Jossey-Bass.

Odiorne, G. S. (1979). M.B.O. II. Fearon-Pitman.

Raia, A. P. (1974). Managing by objectives. Scott Foresman.

Rodgers, R., & Hunter, J. E. (1991). Impact of management by objectives on organizational productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(2), 322-336. doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.322