Table of Contents |

Immigration is a global phenomenon. It affects countries throughout the world, including the United States. It encompasses the movement of millions of individuals and families.

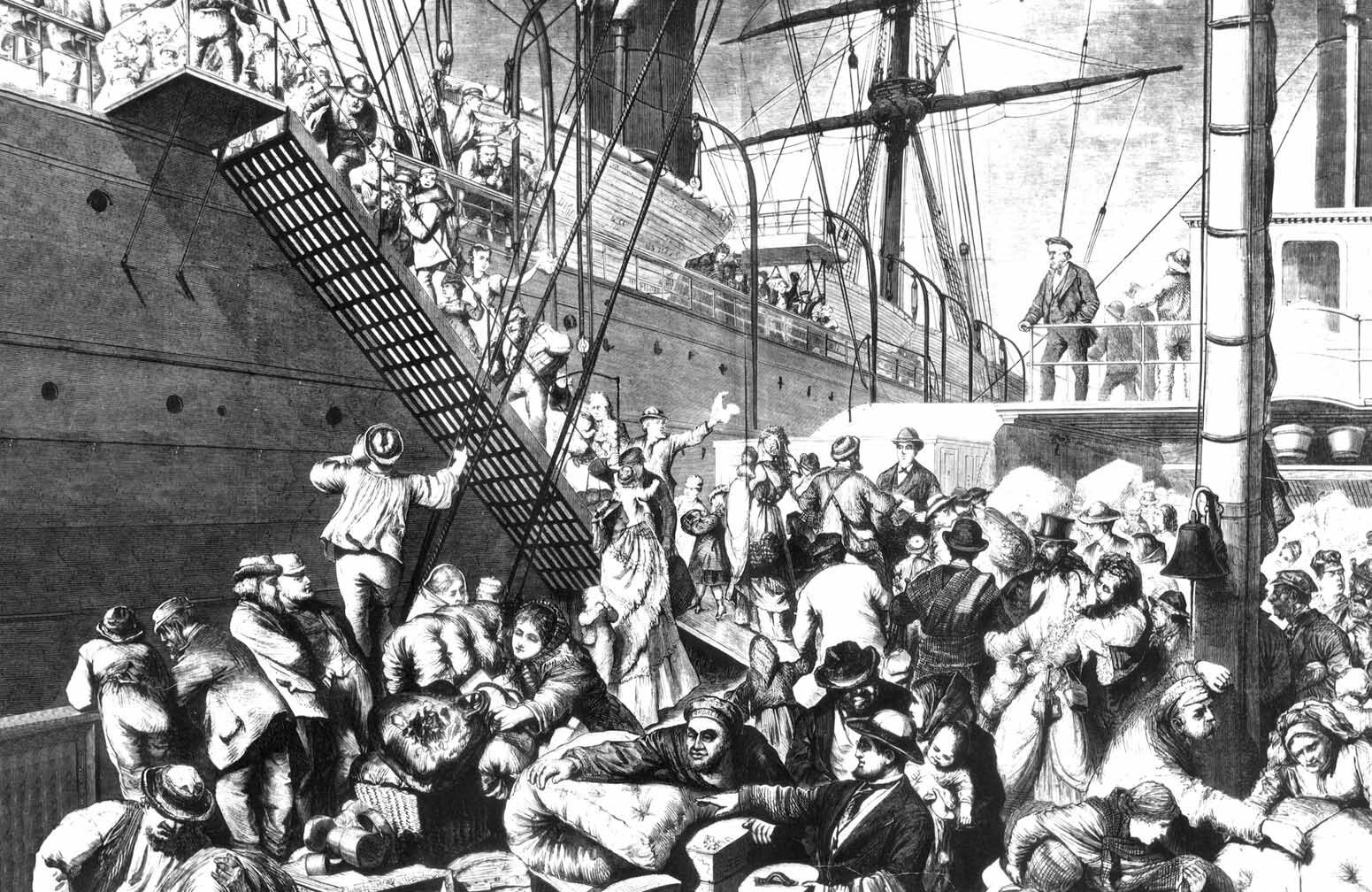

Between 1840 and 1914, when the First World War erupted in Europe, historians estimate that as many as 40 million people migrated to the United States. They came from everywhere—Asia, Europe, Africa, and Central and South America. They came for a variety of reasons: to escape famine and persecution, and to find a better life in a new country.

Immigration to the United States reached its highest levels during the late 19th century. Approximately 12 million immigrants arrived between 1871 and 1901. Close to 3.5 million immigrants entered the United States during the 1890s.

By examining the experiences of immigrants from China and southeastern Europe, you will learn how immigration contributed to the industrialization and urbanization of the United States. You will also see that immigration would not have occurred on the scale that it did without the continued expansion of industries and cities.

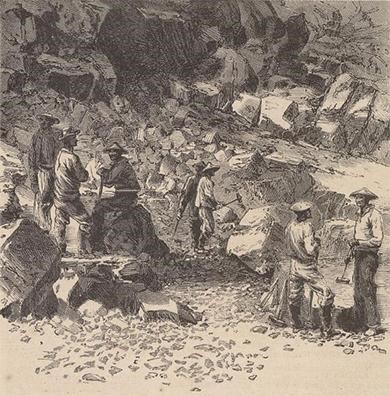

Before the late 19th century, the Chinese population in the United States was small. Beginning with the California Gold Rush when, as historian J. S. Holliday wrote, “the world rushed in” to California to strike it rich, Chinese immigrants arrived in greater numbers.

EXAMPLE

By 1852, over 25,000 Chinese immigrants had arrived in California. By 1880, over 300,000 Chinese lived in the United States, most in California.Although some dreamed of finding gold, many Chinese immigrants found work with the Central Pacific Railroad, which was building the Western branch of the transcontinental railroad.

Most of the Chinese who arrived in the United States were men. Few wives or children immigrated.

Few Chinese immigrants intended to reside permanently in the United States. Many were forced to do so because they did not have enough money for a return trip. Chinese immigrants built communities—centers of mutual support and education—in several Western cities, including San Francisco. These communities included places of worship and health facilities and provided other services to Chinese immigrants.

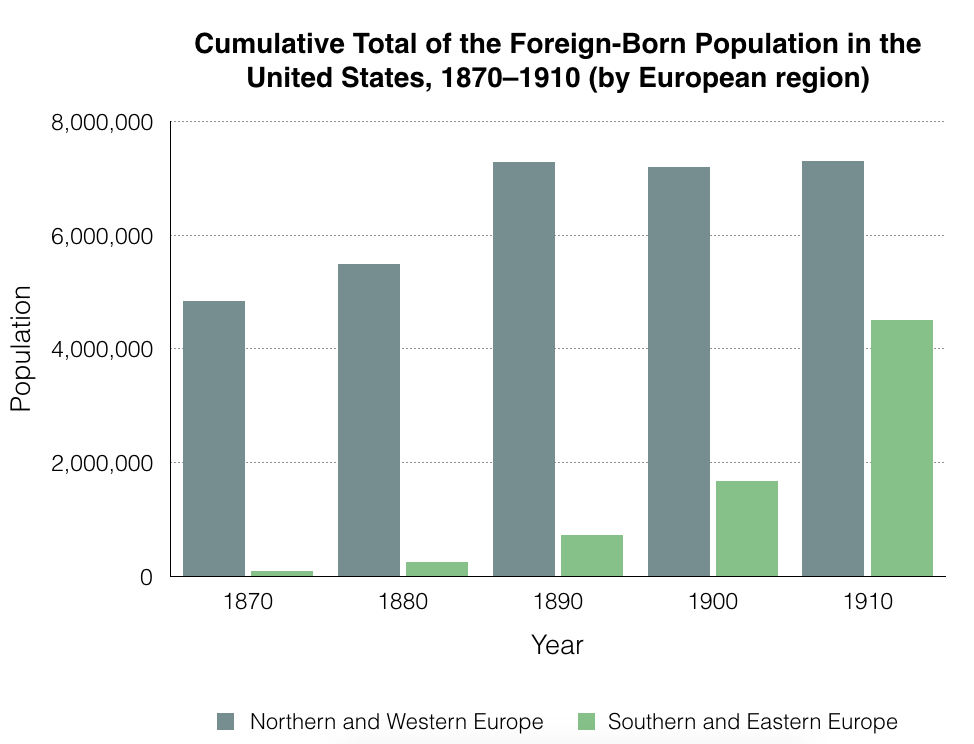

Immigration to the eastern United States took on unique characteristics in the late 19th century. Migrants from northern and western Europe increased throughout the period. Beginning in the 1880s, they were accompanied by an increasing number of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

Immigrants from northern and western Europe, particularly Germany, Great Britain, and the Scandinavian nations, often arrived with some money, which many used to move to the Western territories. However, immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, including Italy, Greece, and Russia, immigrated due to different “push” and “pull” factors.

“Push” factors included the following:

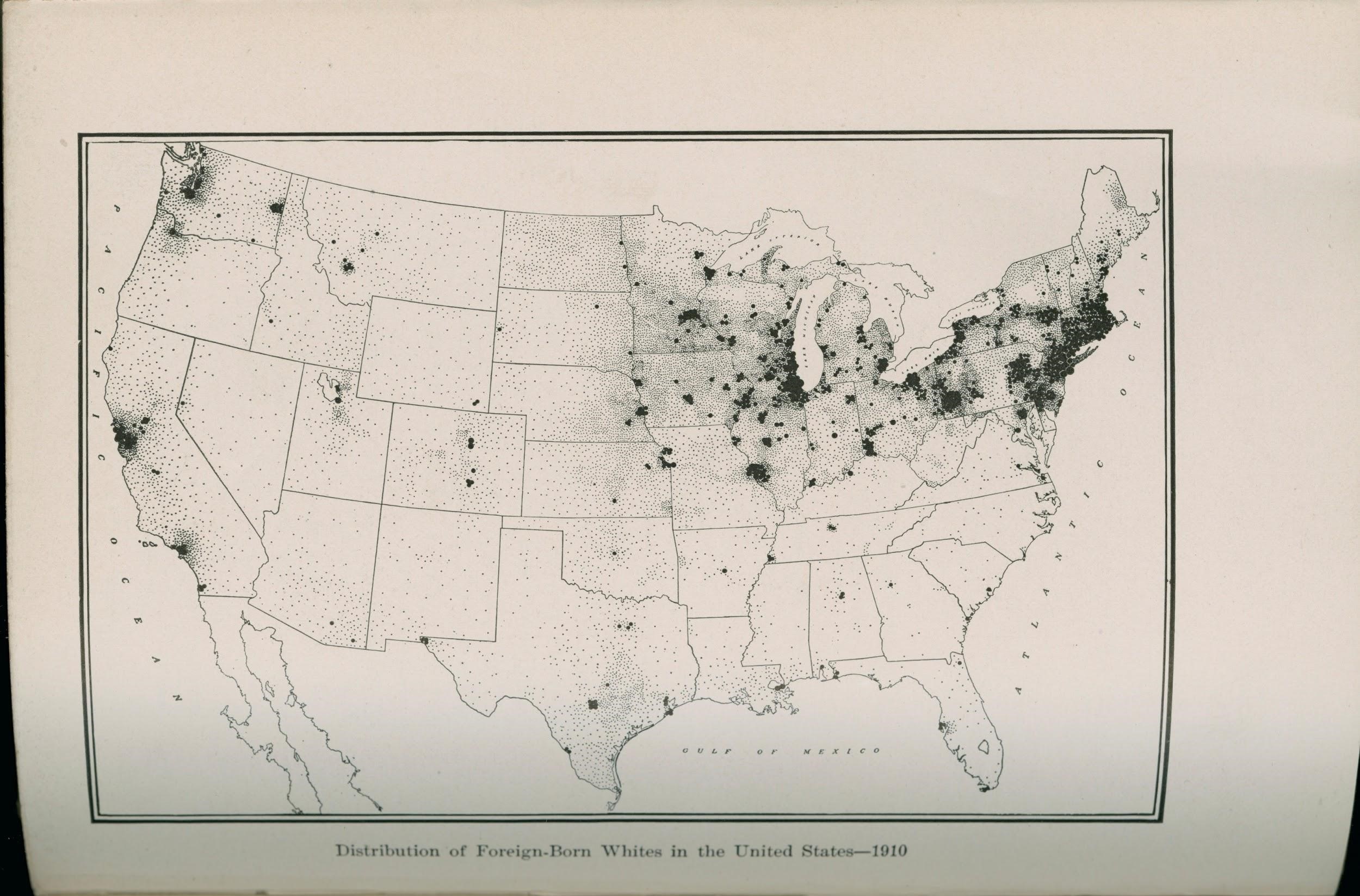

Whatever their reasons for migrating, many immigrants from southern and eastern Europe arrived in the United States with little education or money. They often settled in the ports where they arrived, most notably New York City.

Upon arriving in the United States, Chinese immigrants and those from southern and eastern Europe experienced discrimination. During the Gilded Age, Chinese immigrants were the first to experience discrimination that was sanctioned by Western state governments and, ultimately, by the federal government.

As Chinese workers began competing with White Americans for jobs In California and other Western states, those states developed systems of discrimination. At first, the systems were informal.

EXAMPLE

In the 1870s, groups of White Americans formed “anti-coolie clubs” that boycotted products produced by Chinese workers, and lobbied for immigration restriction laws.Sometimes relations between White and Chinese workers descended into violence.

EXAMPLE

In Rock Springs, Wyoming, in 1885, tensions between White and Chinese miners erupted in a riot that left over two dozen Chinese immigrants dead and many others injured.Racism and discrimination against Chinese immigrants found their way into the law.

EXAMPLE

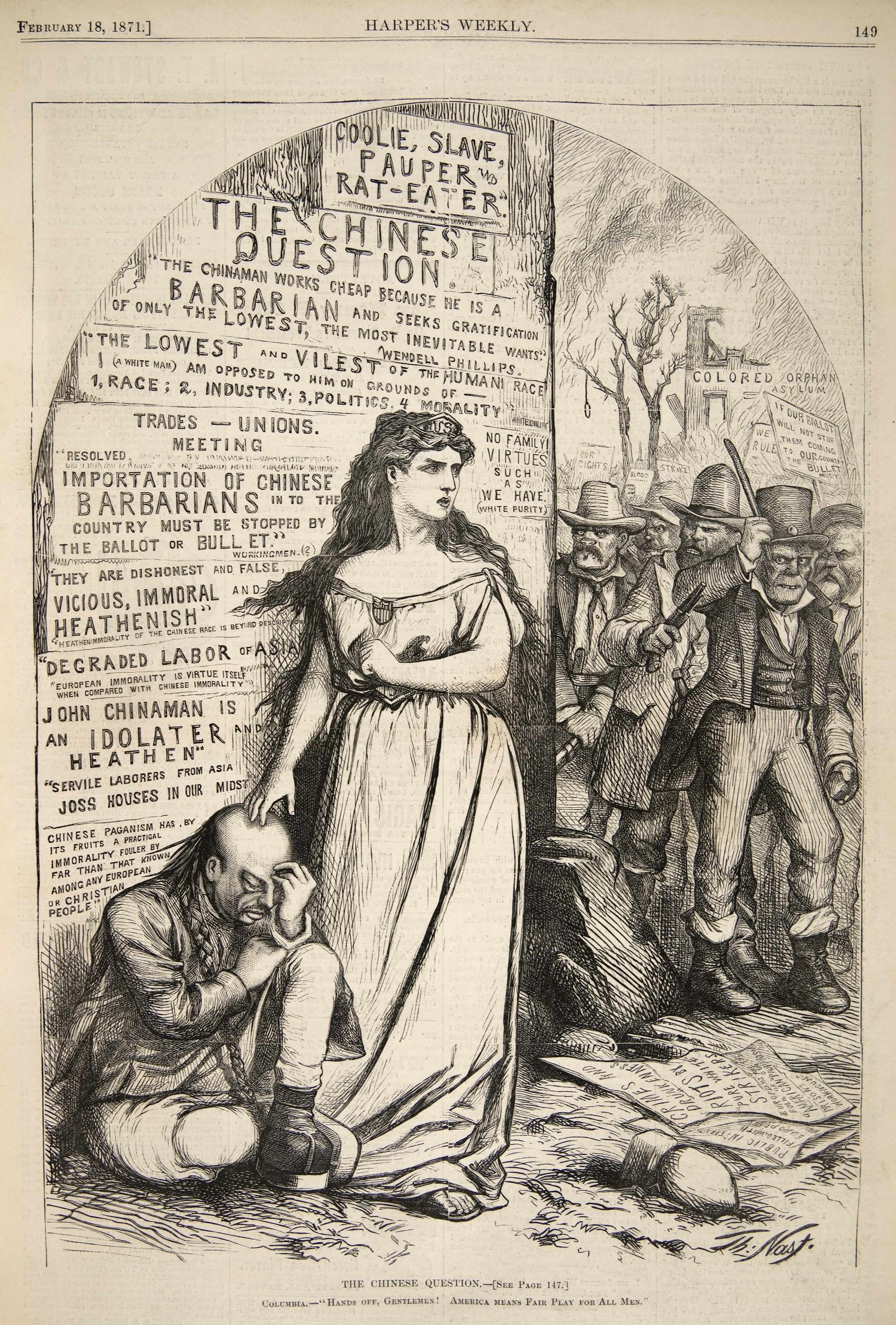

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was the first time that the federal government prevented a specific group of immigrants from entering the country.The press covered American reactions to Chinese immigration. Political cartoons, including those by Thomas Nast, who sympathized with the Chinese immigrants, put opposing views on display.

Examine the political cartoon by Nast, below, which was published in Harper’s Weekly on February 18, 1871. It was created in response to a bill introduced by “Boss” Tweed and the Tammany Hall political machine that would penalize—via fines or imprisonment—any New York business that hired Chinese instead of White workers.

In this image, Columbia (representing the United States) protects a Chinese immigrant from an angry mob, comprised mainly of Irish immigrants from New York City. Columbia says, “Hands off, gentlemen! America means fair play for all men.” Plastered on the wall behind her are numerous slogans, newspaper headlines, and quotations indicating the variety of terms used to demean Chinese immigrants and stoke anti-immigrant sentiment.

The history of Chinese immigration to the United States includes much deprivation and hardship. Due to social discrimination and restrictive laws (like the Chinese Exclusion Act), Chinese immigrants turned to their own communities for support. The assistance they found there sometimes included benevolent associations that defended them against legal and workplace discrimination.

Passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act indicated that the federal government would take a greater role in regulating immigration to the United States. In addition to restricting immigration from China, the federal government sought to manage the flow of immigrants from Europe.

EXAMPLE

In 1891, Congress created the U.S. Bureau of Immigration and, 1 year later, it opened Ellis Island in New York City as a receiving station for European immigrants.At Ellis Island, doctors and nurses examined immigrants upon their arrival, looking for signs of infectious disease and other physical and mental ailments.

Additional Resource

Explore the Ellis Island passenger database on the Ellis Island Foundation website!

Immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were often unable to speak English. They often sought help from relatives, friends, former neighbors, townspeople, and countrymen who lived in New York and other cities. This led to the formation of ethnic enclaves in many cities. Communities like “Little Italy,” “Chinatown,” and others enabled immigrants to stay connected to their cultures by providing home-language newspapers, ethnic food stores, and more. They offered an important sense of community to recent arrivals but also contributed to congestion and other urban problems, particularly in the slums that provided the only affordable housing available to immigrants.

Many immigrants struggled to establish their personal identities in the United States. Mary Antin, who emigrated from Russia with her Jewish family in 1894 (when she was 13 years old), eloquently described the challenges she faced in her autobiography, The Promised Land (1912).

Antin refers to her arrival in the United States as a “second birth.” Her words indicate the break from traditions and customs that immigration required of all immigrants. They also suggest that she could not let go of her past easily. Following is an excerpt from the introduction to her book.

Mary Antin

“Happening when it did, the emigration (from Russia) became of the most vital importance to me personally. All of the processes of uprooting, transportation, replanting, acclimatization, and development took place in my own soul. I felt the pang, the fear, the wonder, and the joy of it. I can never forget, for I bear the scars. But I want to forget—sometimes I long to forget. I think I have thoroughly assimilated my past—I have done its bidding—I want now to be of today. It is painful to be consciously of two worlds…. I am not afraid to live on and on, if only I do not have to remember too much. A long past vividly remembered is like a heavy garment that clings to your limbs when you run. And I have thought of a charm that should release me from the folds of my clinging past. I take the hint from the Ancient Mariner, who told his tale in order to be rid of it. I, too, will tell my tale, for once, and never hark back anymore.”

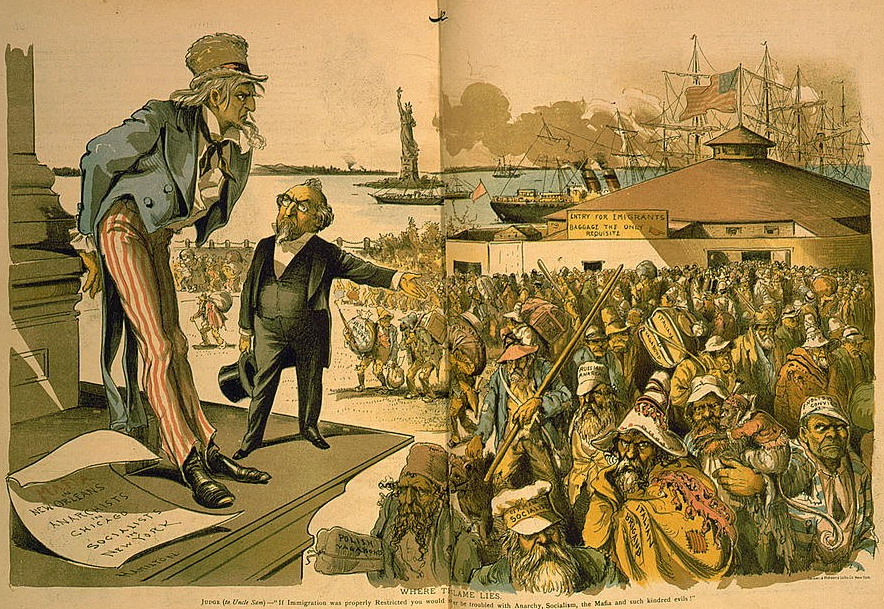

Some native-born Americans expressed concern that immigrants from southern and eastern Europe would hold onto their pasts and, as a result, would not assimilate into American society. Consider the 1891 political cartoon below:

Immigrants had much to offer to American industry and city life. Antin’s autobiography reveals that the experience could have a profound impact on one’s identity. Yet the cartoon above shows that some Americans resented the waves of new immigrants who arrived at the end of the 19th century.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Antin, M., The Promised Land (1912), Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom bit.ly/2moOpuk

Nast, T., “The Chinese Question,” Harper’s Weekly, Feb 18, 1871, Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom bit.ly/2moOpuk

“Distribution of Foreign-Born Whites in the United States--1910,” [map] Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom bit.ly/2moOpuk/