Table of Contents |

Recall that food is converted into chyme in the stomach—going from solid to a soupy mix. As food moves from the small intestine into the large intestine, much of the water that was added to the solid food to make it more easily digested must be reabsorbed. Any undigested materials that remain within the large intestine will be removed as waste, i.e., fecal matter.

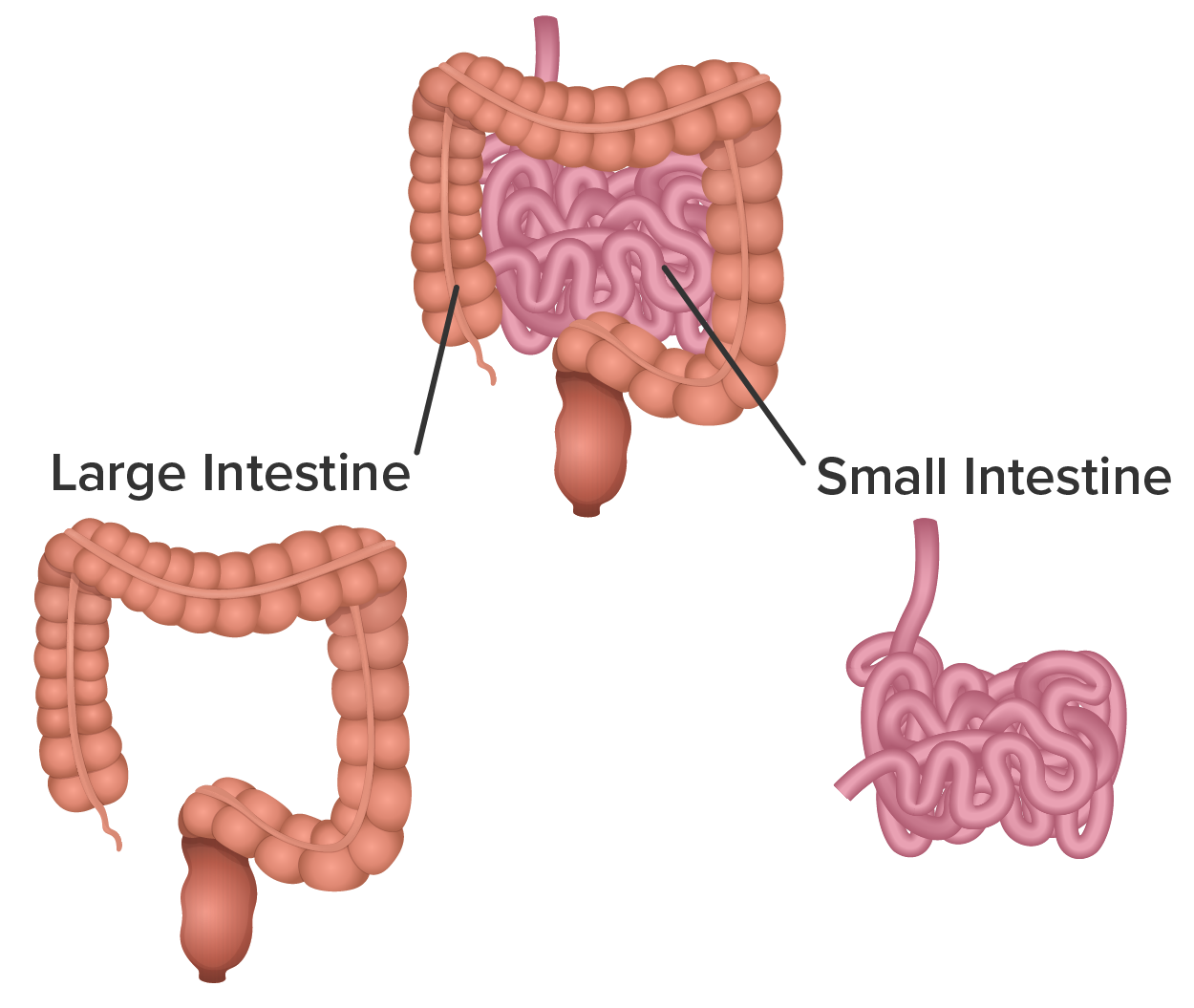

The large intestine is the terminal part of the alimentary canal that follows the small intestine. The large intestine reabsorbs the water from indigestible food material and processes the waste material. It also finishes the absorption of nutrients and synthesizes certain vitamins. The human large intestine is much smaller in length compared with the small intestine but larger in diameter. The image below shows the appearance and location of the large intestine compared with the small intestine.

The large intestine runs from the appendix to the anus. It frames the small intestine on three sides. Despite being about one-half as long as the small intestine, it is called large because it is about 3 inches in diameter, which is more than twice the diameter of the small intestine.

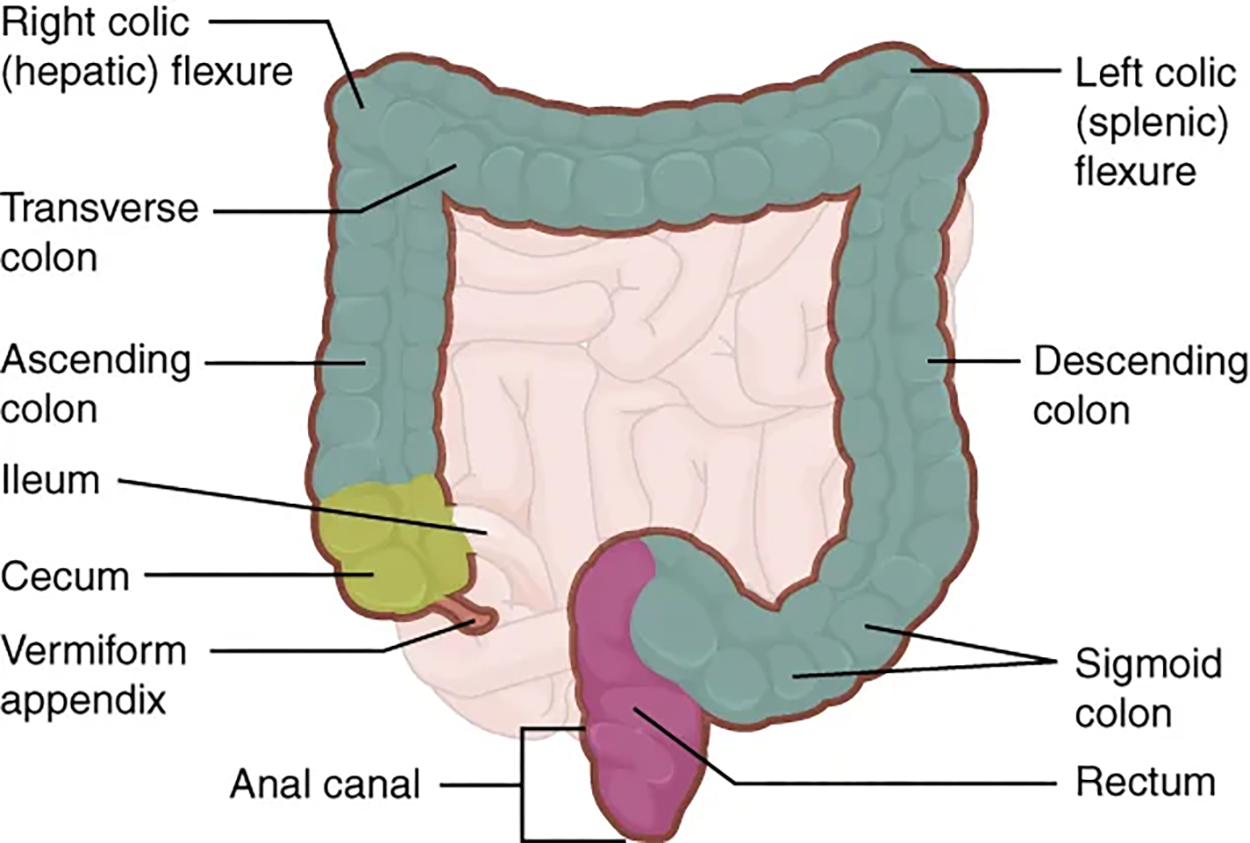

The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: the cecum, the colon, the rectum, and the anal canal. The ileocecal valve, located at the opening between the ileum of the small intestine and the large intestine, controls the flow of chyme from the small intestine to the large intestine.

The first part of the large intestine is the cecum, a sac-like structure that is suspended inferior to the ileocecal valve. It is about 6 cm (2.4 in) long, receives the contents of the ileum, and continues the absorption of water and salts. The appendix (or vermiform appendix) is a winding tube that attaches to the cecum. Although the 7.6-cm-long (3 in) appendix contains lymphoid tissue, suggesting an immunologic function, this organ is generally considered vestigial. However, at least one recent report postulates a survival advantage conferred by the appendix: In diarrheal illness, the appendix may serve as a bacterial reservoir to repopulate the enteric bacteria for those surviving the initial phases of the illness. Moreover, its twisted anatomy provides a haven for the accumulation and multiplication of enteric bacteria. The mesoappendix, the mesentery of the appendix, tethers it to the mesentery of the ileum.

The cecum blends seamlessly with the colon. Upon entering the colon, the food residue first travels up the ascending colon on the right side of the abdomen. At the inferior surface of the liver, the colon bends to form the right colic flexure (hepatic flexure) and becomes the transverse colon. The region defined as the hindgut begins with the last third of the transverse colon and continues on. Food residue passing through the transverse colon travels across to the left side of the abdomen, where the colon angles sharply immediately inferior to the spleen, at the left colic flexure (splenic flexure). From there, food residue passes through the descending colon. After entering the pelvis inferiorly, it becomes the S-shaped sigmoid colon. The ascending and descending colon and the rectum (discussed next) are located in the retroperitoneum. The transverse and sigmoid colon are tethered to the posterior abdominal wall by the mesocolon.

IN CONTEXT

Colorectal Cancer

Each year, approximately 140,000 Americans are diagnosed with colorectal cancer, and another 49,000 die from it, making it one of the deadliest malignancies. People with a family history of colorectal cancer are at increased risk. Smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and a diet high in animal fat and protein also increase the risk. Despite popular opinion to the contrary, studies support the conclusion that dietary fiber and calcium do not reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer may be signaled by constipation or diarrhea, cramping, abdominal pain, and rectal bleeding. Bleeding from the rectum may be either obvious or occult (hidden in feces). Since most colon cancers arise from benign mucosal growths called polyps, cancer prevention is focused on identifying these polyps. The colonoscopy is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Colonoscopy not only allows identification of precancerous polyps, but the procedure also enables them to be removed before they become malignant. Screening with fecal occult blood tests and colonoscopy is recommended for those over 50 years of age.

Food residue leaving the sigmoid colon enters the rectum in the pelvis, which is the final 20.3 cm (8 in) of the alimentary canal. Even though rectum is Latin for “straight,” this structure follows the curved contour of the sacrum and has three bends that create a trio of internal transverse folds called the rectal valves. These valves help separate the feces from gas to prevent the simultaneous passage of feces and gas.

Finally, food residue reaches the last part of the large intestine, the anal canal, which is located completely outside of the abdominopelvic cavity in the perineum. This 3.8- to 5-cm-long (1.5–2 in) structure opens to the exterior of the body at the anus. The anal canal includes two sphincters. The internal anal sphincter is made of smooth muscle, and its contractions are involuntary. The external anal sphincter is made of skeletal muscle, which is under voluntary control. Except when defecating, both usually remain closed.

There are several notable differences between the walls of the large and small intestines.

EXAMPLE

Few enzyme-secreting cells are found in the wall of the large intestine, and there are no circular folds or villi. Other than in the anal canal, the mucosa of the colon is simple columnar epithelium made mostly of enterocytes (absorptive cells) and goblet cells.In addition, the wall of the large intestine has far more intestinal glands, which contain a vast population of enterocytes and goblet cells. These goblet cells secrete mucus that eases the movement of feces and protects the intestine from the effects of the acids and gases produced by enteric bacteria. The enterocytes absorb water and salts as well as vitamins produced by your intestinal bacteria.

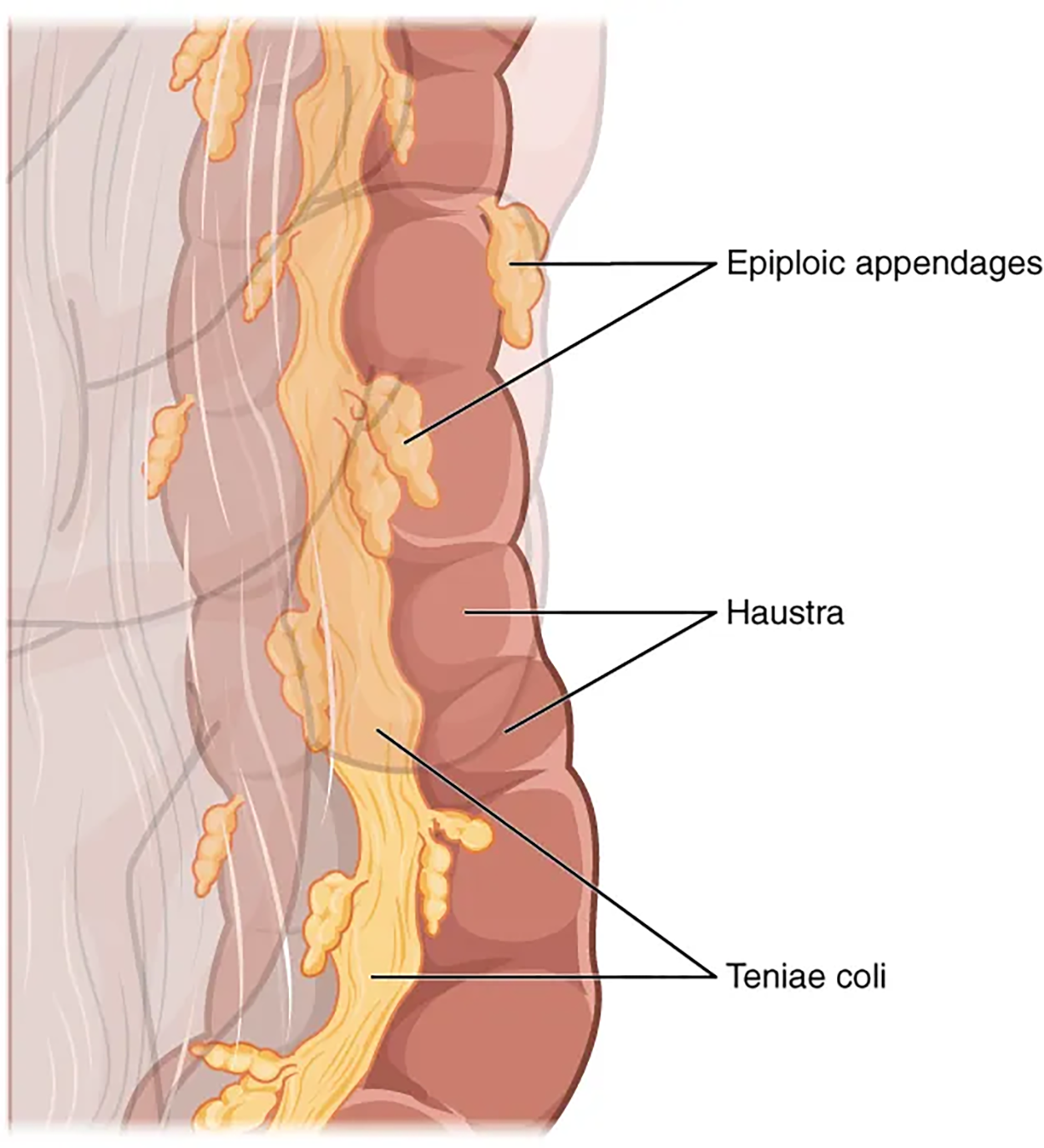

Three features are unique to the large intestine: teniae coli, haustra, and epiploic appendages. The teniae coli (singular = tenia) are three bands of smooth muscle that make up the longitudinal muscle layer of the muscularis of the large intestine, except at its terminal end. Tonic contractions of the teniae coli bunch up the colon into a succession of pouches called haustra (singular = haustrum), which are responsible for the wrinkled appearance of the colon. Attached to the teniae coli are small, fat-filled sacs of visceral peritoneum called epiploic appendages. The purpose of these is unknown. Although the rectum and anal canal have neither teniae coli nor haustra, they do have well-developed layers of muscularis that create the strong contractions needed for defecation.

The stratified squamous epithelial mucosa of the anal canal connects to the skin on the outside of the anus. This mucosa varies considerably from that of the rest of the colon to accommodate the high level of abrasion as feces pass through. The anal canal’s mucous membrane is organized into longitudinal folds, each called an anal column, which house a grid of arteries and veins. Two superficial venous plexuses are found in the anal canal: one within the anal columns and one at the anus.

Depressions between the anal columns, each called an anal sinus, secrete mucus that facilitates defecation. The pectinate line (or dentate line) is a horizontal, jagged band that runs circumferentially just below the level of the anal sinuses and represents the junction between the hindgut and external skin. The mucosa above this line is fairly insensitive, whereas the area below is very sensitive. The resulting difference in pain threshold is due to the fact that the upper region is innervated by visceral sensory fibers, and the lower region is innervated by somatic sensory fibers.

The residue of chyme that enters the large intestine contains few nutrients except water, which is reabsorbed as the residue lingers in the large intestine, typically for 12 to 24 hours. Thus, it may not surprise you that the large intestine can be completely removed without significantly affecting digestive functioning.

EXAMPLE

In severe cases of inflammatory bowel disease, the large intestine can be removed by a procedure known as a colectomy. Often, a new fecal pouch can be crafted from the small intestine and sutured to the anus, but if not, an ileostomy (opening in the abdominal wall) can be created by bringing the distal ileum through the abdominal wall, allowing the watery chyme to be collected in a bag-like adhesive appliance.In the large intestine, mechanical digestion begins when chyme moves from the ileum into the cecum, an activity regulated by the ileocecal sphincter. Right after you eat, peristalsis in the ileum forces chyme into the cecum. When the cecum is distended with chyme, contractions of the ileocecal sphincter strengthen. Once chyme enters the cecum, colon movements begin.

Mechanical digestion in the large intestine includes a combination of three types of movements. The presence of food residues in the colon stimulates a slow-moving haustral contraction. This type of movement involves sluggish segmentation, primarily in the transverse and descending colons. When a haustrum is distended with chyme, its muscle contracts, pushing the residue into the next haustrum. These contractions occur about every 30 minutes, and each last about 1 minute. These movements also mix the food residue, which helps the large intestine absorb water. The second type of movement is peristalsis, which, in the large intestine, is slower than in the above portions of the alimentary canal. The third type is a mass movement. These strong waves start midway through the transverse colon and quickly force the contents toward the rectum. Mass movements usually occur three or four times per day, either while you eat or immediately afterward. Distension in the stomach and the breakdown products of digestion in the small intestine provoke the gastrocolic reflex, which increases motility, including mass movements, in the colon.

IN CONTEXT

You have likely heard that eating fiber, such as from fruits and vegetables, can improve digestion. Fiber in the diet both softens the stool and increases the power of colonic contractions, optimizing the activities of the colon.

Although the glands of the large intestine secrete mucus, they do not secrete digestive enzymes. Therefore, chemical digestion in the large intestine occurs exclusively because of bacteria in the lumen of the colon. Through the process of saccharolytic fermentation, bacteria break down some of the remaining carbohydrates. This results in the discharge of hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane gases that create flatus (gas) in the colon; flatulence is excessive flatus. Each day, up to 1500 mL of flatus is produced in the colon. More is produced when you eat foods such as beans, which are rich in otherwise indigestible sugars and complex carbohydrates like soluble dietary fiber.

Most bacteria that enter the alimentary canal are killed by lysozyme, defensins, HCl, or protein-digesting enzymes. However, trillions of bacteria live within the large intestine and are referred to as the bacterial flora. Most of the more than 700 species of these bacteria are nonpathogenic (non-disease-causing) organisms that cause no harm as long as they stay in the gut lumen. In fact, many facilitate chemical digestion and absorption, and some synthesize certain vitamins, mainly biotin, pantothenic acid, and vitamin K. Some are linked to increased immune response.

A refined system prevents these bacteria from crossing the mucosal barrier. First, peptidoglycan, a component of bacterial cell walls, activates the release of chemicals by the mucosa’s epithelial cells, which draft immune cells, especially dendritic cells, into the mucosa. Dendritic cells open the tight junctions between epithelial cells and extend probes into the lumen to evaluate the microbial antigens. The dendritic cells with antigens then travel to neighboring lymphoid follicles in the mucosa, where T cells inspect for antigens. This process triggers an IgA-mediated response, if warranted, in the lumen that blocks the commensal organisms from infiltrating the mucosa and setting off a far greater, widespread systemic reaction.

The small intestine absorbs about 90% of the water you ingest (either as liquid or within solid food). The large intestine absorbs most of the remaining water, a process that converts the liquid chyme residue into semisolid feces (“stool”). Feces are composed of undigested food residues, unabsorbed digested substances, millions of bacteria, old epithelial cells from the GI mucosa, inorganic salts, and enough water to let it pass smoothly out of the body. Of every 500 mL (17 ounces) of food residue that enters the cecum each day, about 150 mL (5 ounces) become feces.

Feces are eliminated through contractions of the rectal muscles. You help this process by a voluntary procedure called the Valsalva maneuver, in which you increase intra-abdominal pressure by contracting your diaphragm and abdominal wall muscles and closing your glottis.

The process of defecation begins when mass movements force feces from the colon into the rectum, stretching the rectal wall and provoking the defecation reflex, which eliminates feces from the rectum. This parasympathetic reflex is mediated by the spinal cord. It contracts the sigmoid colon and rectum, relaxes the internal anal sphincter, and initially contracts the external anal sphincter. The presence of feces in the anal canal sends a signal to the brain, which gives you the choice of voluntarily opening the external anal sphincter (defecating) or keeping it temporarily closed. If you decide to delay defecation, it takes a few seconds for the reflex contractions to stop and the rectal walls to relax. The next mass movement will trigger additional defecation reflexes until you defecate.

If defecation is delayed for an extended time, additional water is absorbed, making the feces firmer and potentially leading to constipation. On the other hand, if the waste matter moves too quickly through the intestines, not enough water is absorbed, and diarrhea can result. This can be caused by the ingestion of foodborne pathogens. In general, diet, health, and stress determine the frequency of bowel movements. The number of bowel movements varies greatly between individuals, ranging from two or three per day to three or four per week.

IN CONTEXT

Fecal Transplantation

The bacterial flora of our gastrointestinal tract do a host of good things for us. They protect us from pathogens, help us digest our food, and produce some of our vitamins and other nutrients. These activities have been known for a long time. More recently, scientists have gathered evidence that these bacteria may also help control weight by affecting our food choices and absorption patterns. The Human Microbiome Project has begun the process of cataloging our normal bacteria (and archaea) so we can better understand these functions.

A particularly fascinating example of our bacterial flora is related to antibiotic use. People who take high doses of antibiotics tend to lose many of their normal gut bacteria, allowing a naturally antibiotic-resistant species called Clostridium difficile to overgrow and cause severe gastric problems, especially chronic diarrhea. Obviously, trying to treat this problem with antibiotics only makes it worse. However, it has been successfully treated by giving the patients fecal transplants from healthy donors to reestablish the normal intestinal microbial community. In a fecal transplant, fecal material is transferred from a donor (screened for potential pathogens) into the intestines of the recipient patient as a method of restoring the normal microbiota and combating C. difficile infections.

In 2023, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first orally administered fecal microbiota product, a capsule that contains live fecal microbiota spores, to prevent recurrence of C. difficile infection (FDA, 2023).

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION (2) OPENSTAX “CONCEPTS OF BIOLOGY”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/CONCEPTS-BIOLOGY/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSING (1 & 2): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.