Table of Contents |

Childbirth, or parturition, typically occurs within a week of the due date unless the pregnancy involves more than one fetus, which usually causes labor to begin early. As pregnancy progresses into its final weeks, several physiological changes occur in response to hormones that trigger labor.

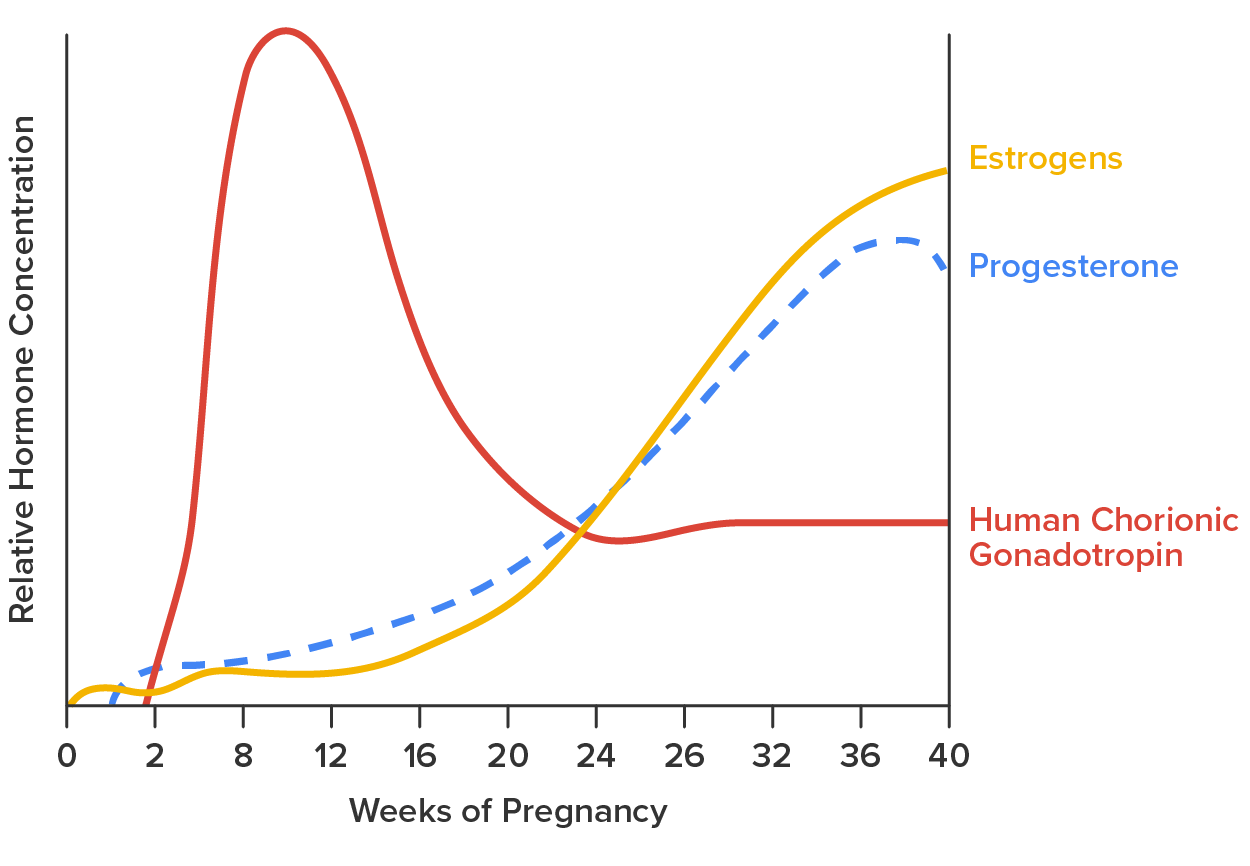

First, recall that progesterone inhibits uterine contractions throughout the first several months of pregnancy. As the pregnancy enters its seventh month, progesterone levels plateau and then drop. Estrogen levels, however, continue to rise in the maternal circulation. The increasing ratio of estrogen to progesterone makes the myometrium (the uterine smooth muscle) more sensitive to stimuli that promote contractions (because progesterone no longer inhibits them). Moreover, in the eighth month of pregnancy, fetal cortisol rises, which boosts estrogen secretion by the placenta and further overpowers the uterine-calming effects of progesterone. Some people may feel the result of the decreasing levels of progesterone in late pregnancy as weak and irregular peristaltic Braxton Hicks contractions, also called false labor. These contractions can often be relieved with rest or hydration.

A common sign that labor will be soon is the so-called “bloody show.” During pregnancy, a plug of mucus accumulates in the cervical canal, blocking the entrance to the uterus. Approximately 1–2 days before the onset of true labor, this plug loosens and is expelled, along with a small amount of blood.

Meanwhile, the posterior pituitary has been boosting its secretion of oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates the contractions of labor. At the same time, the myometrium increases its sensitivity to oxytocin by expressing more receptors for this hormone. As labor nears, oxytocin begins to stimulate stronger, more painful uterine contractions, which—in a positive feedback loop—stimulate the secretion of prostaglandins from fetal membranes. Like oxytocin, prostaglandins also enhance uterine contractile strength. The fetal pituitary also secretes oxytocin, which increases prostaglandins even further. Given the importance of oxytocin and prostaglandins in the initiation and maintenance of labor, it is not surprising that, when a pregnancy is not progressing to labor and needs to be induced, a pharmaceutical version of these compounds (called Pitocin) is administered by intravenous drip.

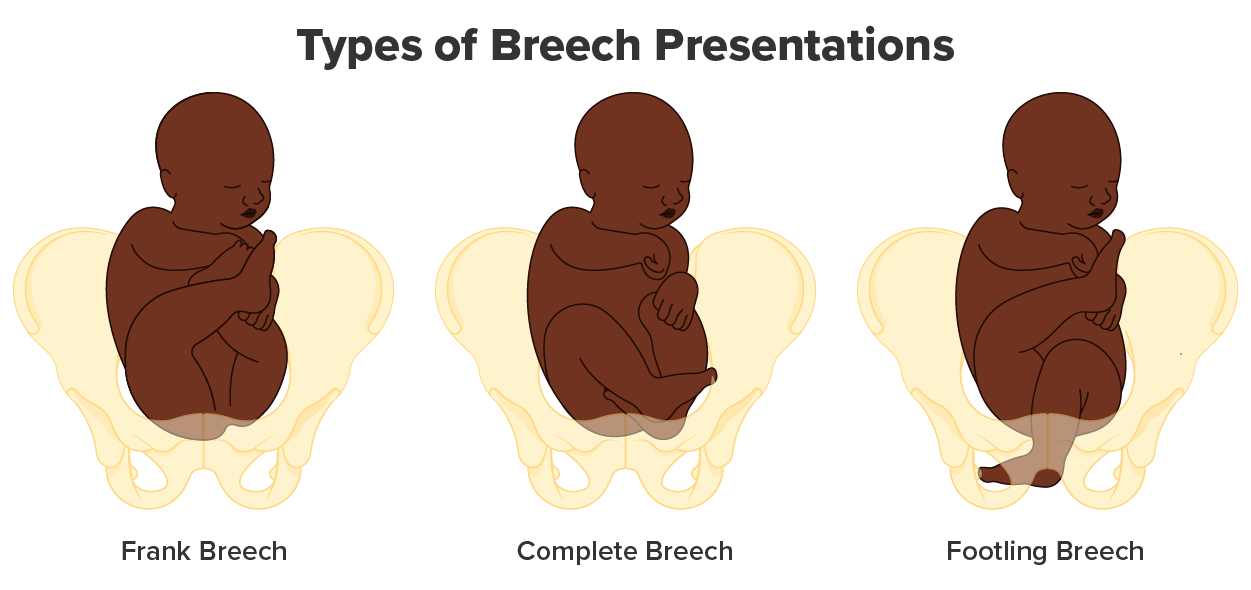

Finally, stretching of the myometrium and cervix by a full-term fetus in the vertex (head-down) position stimulates uterine contractions. The sum of these changes initiates the regular contractions known as true labor, which become more powerful and more frequent with time. The pain of labor is attributed to myometrial hypoxia during uterine contractions.

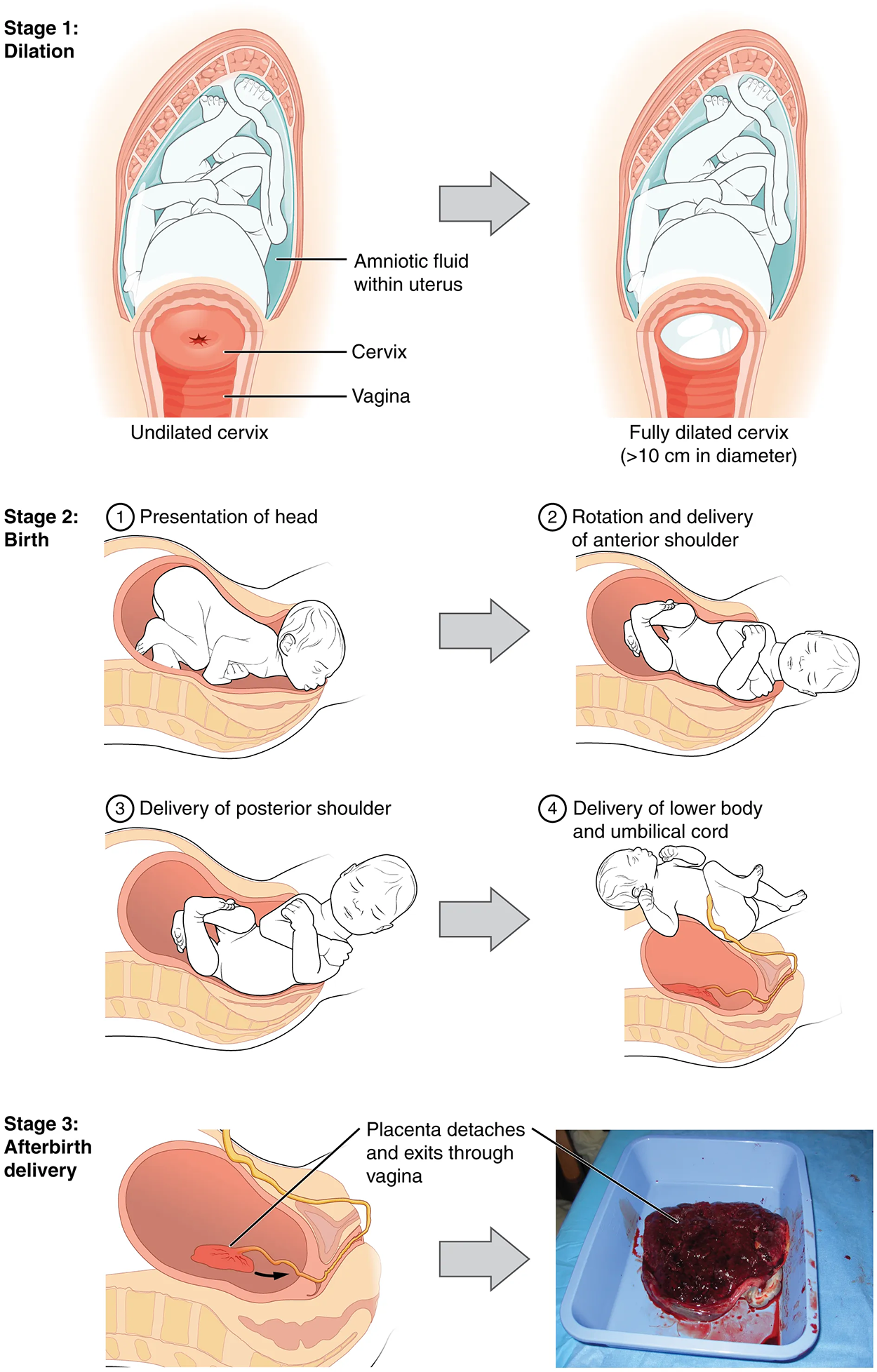

The process of childbirth can be divided into three stages: cervical dilation, expulsion of the newborn, and afterbirth (as shown in the image below).

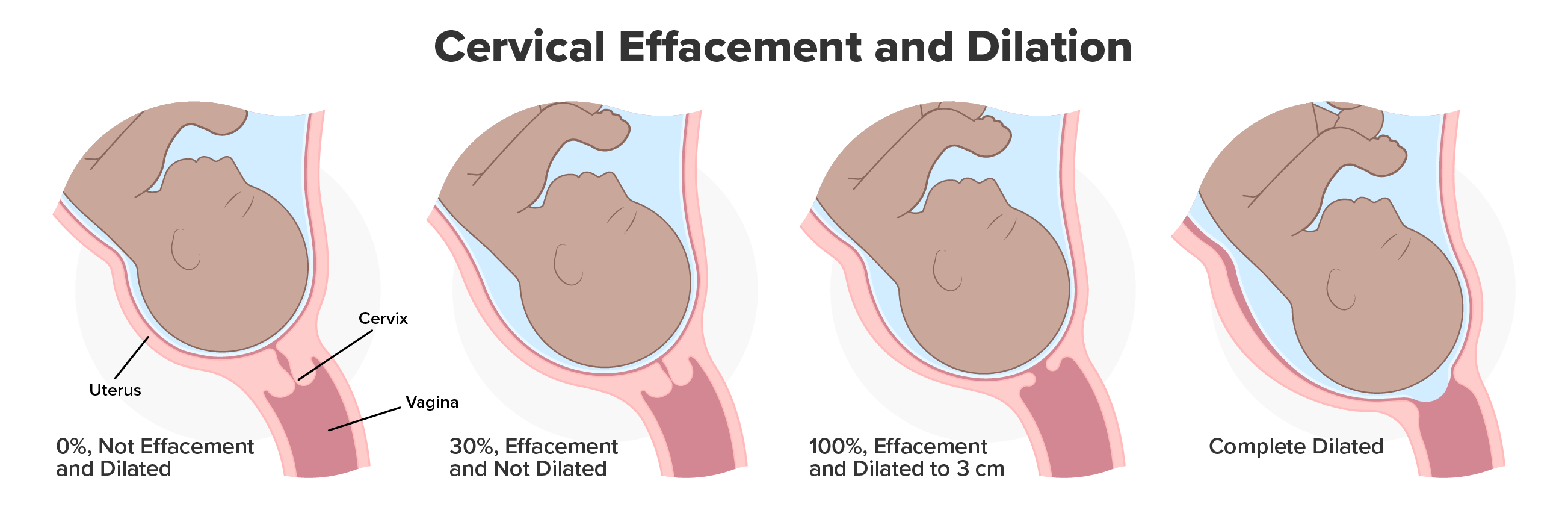

For vaginal birth to occur, the cervix must dilate fully to 10 cm in diameter—wide enough to deliver the newborn’s head. The dilation stage is the longest stage of labor and typically takes 6–12 hours. However, it varies widely and may take minutes, hours, or days, depending in part on whether the person has given birth before; in each subsequent labor, this stage tends to be shorter.

True labor progresses in a positive feedback loop in which uterine contractions stretch the cervix, causing it to dilate and efface, or become thinner. Cervical stretching induces reflexive uterine contractions that dilate and efface the cervix further. In addition, cervical dilation boosts oxytocin secretion from the pituitary, which in turn triggers more powerful uterine contractions. When labor begins, uterine contractions may occur only every 3–30 minutes and last only 20–40 seconds; however, by the end of this stage, contractions may occur as frequently as every 1.5–2 minutes and last for a full minute.

Each contraction sharply reduces oxygenated blood flow to the fetus. For this reason, it is critical that a period of relaxation occur after each contraction. Fetal distress, measured as a sustained decrease or increase in the fetal heart rate, can result from severe contractions that are too powerful or lengthy for oxygenated blood to be restored to the fetus. Such a situation can cause an emergency birth with a vacuum, forceps, or surgically by Caesarian section.

The amniotic membranes rupture before the onset of labor in about 12% of people; they typically rupture at the end of the dilation stage in response to excessive pressure from the fetal head entering the birth canal.

The expulsion stage begins when the fetal head enters the birth canal and ends with the birth of the newborn. It typically takes up to 2 hours, but it can last longer or be completed in minutes, depending in part on the orientation of the fetus. The vertex presentation—known as the occiput anterior vertex—is the most common and is associated with the greatest ease of vaginal birth. The fetus faces the maternal spinal cord and the smallest part of the head (the posterior aspect called the occiput) exits the birth canal first.

Vaginal birth is associated with significant stretching of the vaginal canal, the cervix, and the perineum. Until recent decades, it was a routine procedure for an obstetrician to numb the perineum and perform an episiotomy, an incision in the posterior vaginal wall and perineum. The perineum is now more commonly allowed to tear on its own during birth. Both an episiotomy and a perineal tear need to be sutured shortly after birth to ensure optimal healing. Although suturing the jagged edges of a perineal tear may be more difficult than suturing an episiotomy, tears heal more quickly, are less painful, and are associated with less damage to the muscles around the vagina and rectum.

Upon the birth of the newborn’s head, an obstetrician will aspirate mucus from the mouth and nose before the newborn’s first breath. Once the head is birthed, the rest of the body usually follows quickly. The umbilical cord is then double-clamped, and a cut is made between the clamps. This completes the second stage of childbirth.

The delivery of the placenta and associated membranes, commonly referred to as the afterbirth, marks the final stage of childbirth. After the expulsion of the newborn, the myometrium continues to contract. This movement shears the placenta from the back of the uterine wall. It is then easily delivered through the vagina. Continued uterine contractions then reduce blood loss from the site of the placenta. If the placenta does not birth spontaneously within approximately 30 minutes, it is considered retained, and the obstetrician may attempt manual removal. If this is not successful, surgery may be required.

The obstetrician must examine the expelled placenta and fetal membranes to ensure that they are intact. If fragments of the placenta remain in the uterus, they can cause postpartum hemorrhage. Uterine contractions continue for several hours after birth to return the uterus to its pre-pregnancy size in a process called involution, which also allows the abdominal organs to return to their pre-pregnancy locations. Breastfeeding facilitates this process. Although postpartum uterine contractions limit blood loss from the detachment of the placenta, the person who has recently given birth does experience a postpartum vaginal discharge called lochia. This is made up of uterine lining cells, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and other debris. Thick, dark, lochia rubra (red lochia) typically continues for 2–3 days and is replaced by lochia serosa, a thinner, pinkish form that continues until about the 10th postpartum day. After this period, a scant, creamy, or watery discharge called lochia alba (white lochia) may continue for another 1–2 weeks.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.