Table of Contents |

The frescoes that you will be looking at today date from between 1597 to 1694, covering almost 100 years, and focus geographically on Italy.

Ceiling frescoes represent a fascinating subcategory of mural painting, distinguished not by their technique but by their unique spatial challenges and visual impact. Artists leverage the expansive surfaces of ceilings to create awe-inspiring scenes that often seem to defy gravity, transforming architectural spaces into realms of myth, religion, and grandeur.

Annibale Carracci (1560–1609) was a pioneering Italian Baroque painter known for his mastery in various painting techniques, including quadro riportato. This technique, which translates to “transported painting,” involves creating ceiling frescoes that resemble framed easel paintings. Notice the illusion of the frames around each painting, as if they are each separate artworks rather than one large cohesive narrative.

Carracci's use of quadro riportato is most famously exemplified in his work The Loves of the Gods, painted on the ceiling of the Galleria Farnese in the Palazzo Farnese, Rome. Despite the separation of scenes by frames, Carracci's careful arrangement and thematic consistency ensure that the overall composition remains harmonious and coherent.

The Loves of the Gods

Rome

1597

Fresco

The fresco series is a visual celebration of mythological narratives, focusing on the romantic and often tumultuous relationships between gods and mortals. This thematic choice allowed Carracci to explore a wide range of emotions and interactions, from tender affection to passionate embrace.

Couples such as Perseus and Andromeda are reproduced below. Here, Perseus can be seen on Pegasus, ready to turn the Kraken to stone with Medusa’s severed head.

Another significant scene features Jupiter, the king of the gods, and his wife Juno in a moment of divine splendor, reflecting the power dynamics and romantic tensions between the divine couple.

This final example is the triumphant central image of The Loves of the Gods fresco series. The scene depicts the joyous procession of Bacchus, the god of wine, and Ariadne, his mortal lover, surrounded by a lively entourage of satyrs and nymphs.

Carracci’s style recalls Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes as well as the colors of Titian. His use of illusionism or perspective to creative three-dimensional space—in particular the painted frames that set the images apart from each other—is indicative of a stylistic element that was pervasive in the ceiling frescoes of the 17th century.

Carracci's project was a collaborative effort, involving his brother Agostino and cousin Ludovico, both accomplished painters. This family workshop approach was typical of the Carracci studio and contributed to the cohesive execution of the frescoes.

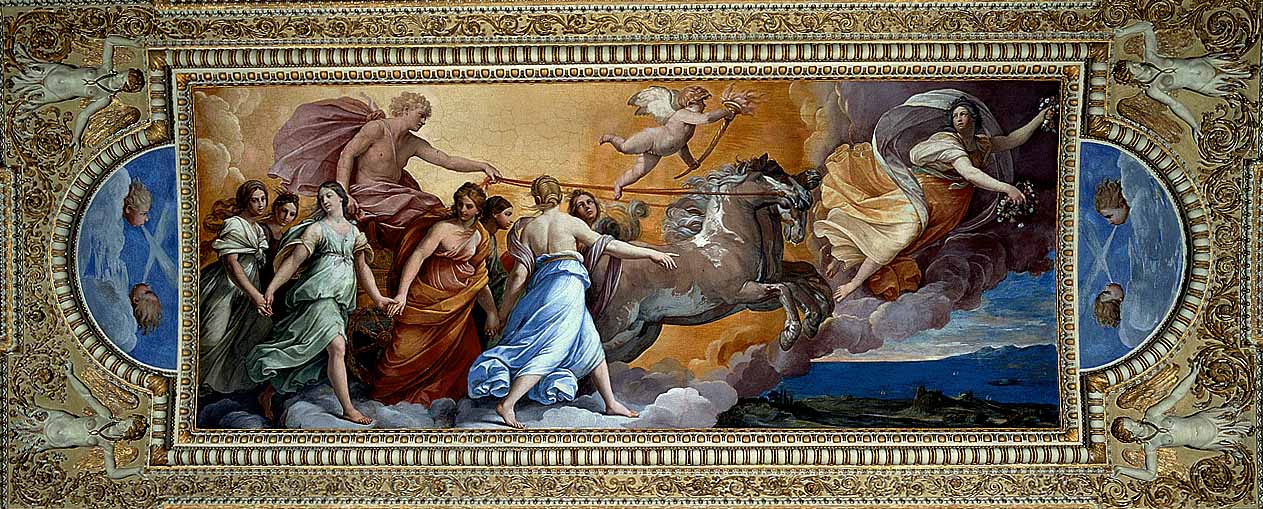

Guido Reni trained in the same Bologna art academy as Carracci. In a fashion similar to his contemporary’s work, Guido’s Aurora is surrounded by a very convincing, albeit painted, frame. It depicts Aurora leading Dawn (in the chariot) and his entourage across the sky, bringing forth a new day.

Aurora

Rome

1614

Fresco

This artist shows influence from classical Roman triumphal processions as well as from Renaissance masters, such as Raphael, in his depiction of forms.

Guido Reni (1575–1642) trained at the same Bolognese art academy as Annibale Carracci. Known for his classical approach and graceful style, Reni’s works often depict mythological and religious themes with a sense of elegance and clarity.

No stranger to elaborate depictions glorifying his family, Pope Urban VIII commissioned the ceiling fresco seen below by the artist Pietro da Cortona as a way of commemorating his family and ensuring their legacy in the hearts and minds of the people. It’s an amazing example of the di sotto in sù (literally translated means “from below, upward”) technique in which the ceiling appears to be blown through the roof, revealing Divine Providence with the halo, directing Immortality, who is placing a crown of stars that symbolize eternal life on the Barberini family.

Triumph of the Barberini

National Galleries of Ancient Art, Palazzo Barberini

1633–1639

Fresco

The personifications of Hope, Charity, and Faith hold a wreath that encircles three bees, the symbol of the Barberini family, in the center. This symbol can also be seen on the St. Peter’s Basilica baldacchino by Bernini—also commissioned by Pope Urban VIII.

Giovanni Battista Gaulli (1639–1709), also known as Baciccio, was an Italian Baroque painter renowned for his dramatic ceiling frescoes. One of his most celebrated works is the Triumph of the Name of Jesus, located in the Church of the Gesù in Rome. This fresco is a quintessential example of Baroque art's ability to convey religious fervor and divine splendor, reflecting the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation ideals.

Triumph of the Name of Jesus

Church of the Gesù

1672–1677

Fresco

The artistry exhibited is remarkable. The painting is so well integrated with the architecture that it’s nearly impossible to discern what is real and what is painted. It is an excellent example of an architectural trick of the eye, or trompe l’oeil, also known as quadratura.

The fresco depicts the glorification of the name of Jesus (IHS), surrounded by heavenly hosts and divine light. It is an allegory of the triumph of the Catholic faith and the divine grace it bestows upon the faithful. Yet it is almost invisible because of the backdrop of blinding light from heaven, a stark contrast with the dark shadow of sinners falling back to earth.

Andrea Pozzo (1642–1709) was an Italian Jesuit brother, painter, and architect known for his mastery of illusionistic ceiling painting. His fresco Glorification of Saint Ignatius stands as a testament to Pozzo's genius in blending art, architecture, and theology.

Glorification of Saint Ignatius is located in the Church of Sant'Ignazio, the Roman church dedicated to Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order. The fresco depicts the apotheosis of Saint Ignatius, showing him ascending to heaven and being welcomed by Christ. Surrounding him are allegorical figures representing the four continents—Asia, Africa, Europe, and America—symbolizing the global reach of the Jesuit missions.

Glorification of Saint Ignatius

Rome

1685–1694

Fresco

Pozzo extends the architecture of the church through painting, creating the impression of tremendous verticality that opens upward towards heaven, in the figure of Christ with Saint Ignatius rising toward his savior.

Again, it’s nearly impossible to tell where the real architecture ends and the painting begins, creating a truly awe-inspiring sensation and tremendously spiritual moment for the pious observer below.

Here’s another view of the quadratura-rendered architecture extending and creating a sense of verticality:

Through his expert use of trompe l’oeil and quadratura, Pozzo created a fresco that not only captivates the viewer with its visual brilliance but also conveys a powerful religious message. The fresco stands as a testament to Pozzo’s artistic genius and his contribution to the Baroque period’s artistic and religious heritage.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY IAN MCCONNELL AND TAMORA KOWALSKI FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.