Table of Contents |

So far, we have learned how to write programs and communicate our intentions to the Central Processing Unit using conditional statements, functions, and iterations. The Central Processing Unit is the brain of any computer. It is what runs the software that we write. It’s also called the “CPU” or the “processor”. We have learned how to create and use data structures in the Main Memory. The Main Memory is used to store information that the CPU needs in a hurry. The main memory is nearly as fast as the CPU. The CPU and Main Memory are where our software works and runs. It is where all of the “thinking” happens.

Once the power is turned off, anything stored in either the CPU or Main Memory is erased. Up to now, our programs have just been transient fun exercises to learn Python. Now we will start to work with Secondary Memory (or files). Secondary Memory is also used to store information, but it is much slower than Main Memory. The advantage of Secondary Memory is that it can store information even when there is no power to the computer. Examples of Secondary Memory are a USB flash drive or hard drive. If we store our information on a USB flash drive, the information can be removed from the system and transported to another system. We will primarily focus on reading and writing text files such as those we create in a text editor.

When we want to read or write a file (say on your hard drive), we first must open the file. Opening the file communicates with your operating system, which knows where the data for each file is stored. When you open a file, you are asking the operating system to first find the file by name and make sure the file exists, and then make its contents available (open) for reading or writing. When a stored file (data that is stored in Secondary Memory in a file or drive) is initially opened, it is moved from Secondary Memory to Main Memory where the CPU can use it. In the example (below), we open the file poem.txt, which should be stored in the same folder as the main.py file. In Replit, we can create a file, name it poem.txt and add in the following text:

Roses Are Red,

Violets are blue,

Sugar is sweet,

And so are you.

To do so:

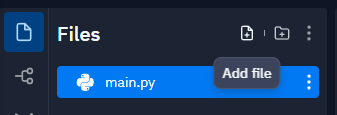

1. Click on the ‘Add file’ icon at the top of the Files panel.

2. Next, we name the file; in this case, we will call it poems.txt. Remember, if you do not give a filename an extension, the default of .py will be added. We do not want a .py file, so we needed to add the .txt to make it a text file.

3. Then we can paste in the code.

Directions: Try following the steps above to create a new file and add some code.

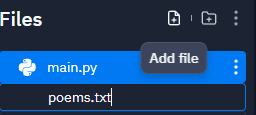

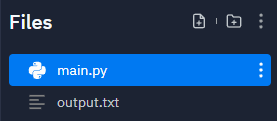

Notice that the icon for our poem.txt looks different than our main.py file. The .py extension indicates that this is a Python file and all Python files are modules that can be imported. No other extension (including .txt files) can be used as modules.

Now that our poem.txt file has information, let’s try to read the file. We need to move back to the main.py file to add the following code.

EXAMPLE

fhandler = open('poem.txt')

print(fhandler)

Here is that output.

<_io.TextIOWrapper name='poem.txt' mode='r' encoding='UTF-8'>

Directions: Try adding the following code to the main.py file and running the program.

Not seeing the poem? That is because at this point we only opened up the file and we haven't read any data from the file. The output we see is just information pointing to the file. We added a variable called fhandler (file handler) and used the open() function on our poem.txt file. The open() function returns a file object. The open() function contains options for reading the content of the file.

Central Processing Unit

The Central Processing Unit is the heart of any computer. It is what runs the software that we write; it is also called the “CPU” or the “processor”.

Main Memory

The Main Memory is used to store information that the CPU needs in a hurry. Main memory is nearly as fast as the CPU. The CPU and memory are where our software works and runs.

Secondary Memory

Secondary Memory is also used to store information, but it is much slower than the Main Memory. The advantage of the Secondary Memory is that it can store information even when there is no power to the computer.

open()

The open() function returns a file object. The open() function contains options for reading the content of the file.

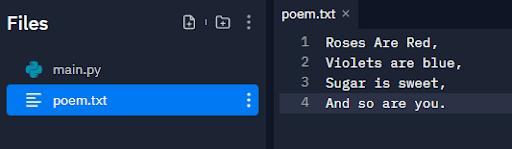

If the opening of a file is successful, the operating system returns a file handle. The file handle is not the actual data contained in the file, but instead it is a “handle” that we can use to read the data. Think of the file handle as being an address to a house. With the address to a house, you know where the house is but the address itself is just pointing to the house location in the same way that a file handle is pointing to a file. You are given a handle if the requested file exists and you have the proper permissions to read the file. If the file does not exist, open will fail with a traceback error and you will not get a handle to access the contents of the file.

Here is an example of a file that does not exist that we are trying to open.

EXAMPLE

fhandler = open('nofile.txt')

print(fhandler)

And here is the traceback error.

Trackback (most recent call last):

File "main.py", line 1, in <module>

fhandler = open('nofile.txt')

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'nofile.txt'

A text file can be thought of as a sequence of lines, much like a Python string can be thought of as a sequence of characters. The poem.txt file simply contains four lines of text for the poem.

While the file handle does not contain the data for the file, it is quite easy to construct a for loop to read through and count each of the lines in a file.

EXAMPLE

fhandler = open('poem.txt')

count = 0

for line in fhandler:

count = count + 1

print('Line Count:', count)

This simple program gives the following output.

Line Count: 4

Directions: Try using the open() function and for loop to count the lines of our poem.txt file.

We can use the file handle as the sequence in our for loop. Our for loop simply counts the number of lines in the file and prints the final total out. The rough translation of the for loop into English is, “for each line in the file represented by the file handle, add one to the count variable.” We could call this pseudocode as it helps explain the details. The reason that the open() function does not read the entire file is that the file might be quite large with many gigabytes of data. The for loop takes the same amount of time to read a line regardless of the size of the file. The for loop is actually what causes the data to be read from the file.

When the file is read using a for loop in this manner, Python takes care of splitting the data in the file into separate lines using the newline character. Python reads each line through the newline and includes the newline as the last character in the line variable for each iteration of the for loop.

The newline character is a whitespace character similar to the space and tab character; it is not shown as a ‘\ ‘ (space) or a ‘\t’ (tab). Even though the newline character is stored as a ‘\n’ (newline), we do not see that character as a ‘\n’ but rather we see the text moving to the next line.

Because the for loop reads the data one line at a time, it can efficiently read and count the lines in very large files without running out of Main Memory to store the data. The above program can count the lines in any size file using very little memory since each line is read, counted, and then discarded.

If you know the file is relatively small compared to the size of your Main Memory, you can read the whole file into one string using the .read() method on the file handle. The .read() method reads the entire file and returns the entire contents as a string. An example of something that may not fit into memory could be a full 4K movie file.

Here is an example of how to use the .read() method to return the full information in a file.

EXAMPLE

fhander = open('poem.txt')

text = fhander.read()

print(text)

This would be the output.

Roses are Red,

Violets are blue,

Sugar is sweet,

And so are you.

In this example, the entire contents of the file poem.txt are read directly into the variable text. When the file is read in this manner, all the characters—including all of the lines and newline characters—are one big string in the variable text. Remember that this form of reading the data should only be used if the file data will fit comfortably in the Main Memory of your computer. If the file is too large to fit in Main Memory, you should work with parts of it at a time in your program. This is also where tools like databases become very useful.

Directions: Now try to use the .read() method and see if you can output the contents of our poem.txt file.

File Handle

The file handle is not the actual data contained in the file, but instead, it is a “handle” that we can use to read the data.

.read()

The .read() method reads the entire file and returns the entire contents as a string.

Earlier we mentioned that the open() function contains options for reading the content of the file. The open() function by default allows us to read the file but we can also pass in ‘r’ as the second parameter (called mode) to do the same thing.

EXAMPLE

fout = open('output.txt', 'r')

To write to a file, we use the open() function with the mode ‘w’ as a second parameter of the open() function.

EXAMPLE

fout = open('output.txt', 'w')

If the file already exists, opening it in write (‘w’) mode clears out the old data and starts fresh, so be careful!

If the file doesn’t exist, a new one is created. The .write() method of the file handle object writes a specified text to the file, returning the number of characters written. The default write mode is text for writing (and reading) strings.

EXAMPLE

fout = open('output.txt', 'w')

line1 = "Putting in a line of text,\n"

fout.write(line1)

Here we created a variable called fout (file out) that uses the open() function with the ‘w’ (write) in the second parameter. Next, we created variable line1 and assigned it a string with a newline character at the end. Finally, we are using the .write() method to write line1 to our output.txt file.

Notice that the file is created if we run this code.

Directions: Go ahead and try to run the code above in the main.py file to write to a file called output.txt.

Again, the file handle keeps track of where it is, so if you call the .write() method again, it adds the new data to the end of the file. We will cover some of the other ways to manipulate files in the next lesson.

Did you notice nothing has been added to the output.txt file? Did you look? That is because when you write to a file, it is similar to writing in Microsoft Word; unless you save it, your work will be lost. Python has a “save” feature—it’s called the .close() function, coming up next.

.write()

The .write() method of the file handle object writes a specified text to the file, returning the number of characters written.

When you are done writing, you have to close the file to make sure that the last bit of data is saved so it will not be lost if the power goes off.

Here is our last example with a new statement line at the end.

EXAMPLE

fout = open('output.txt', 'w')

line1 = "Putting in a line of text,\n"

fout.write(line1)

fout.close()

The .close() method of the file handle object closes an open file. We could call the .close() method after we open a file for reading, but that can add unnecessary lines of code to a program if we are only opening a few files for reading, since Python makes sure that all open files are closed when the program ends. However, when we are writing files, we want to explicitly close the files if we made changes (wrote anything to them); otherwise, the changes will not be saved.

Directions: Now try adding the .close() method to your program and running it again. Now that we added the .close() method, you should see the string in our output.txt file.

.close()

The .close() method of the file handle object closes an open file.

Source: THIS CONTENT AND SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM “PYTHON FOR EVERYBODY” BY DR. CHARLES R. SEVERANCE ACCESS FOR FREE AT www.py4e.com/html3/ LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 3.0 UNPORTED.