Table of Contents |

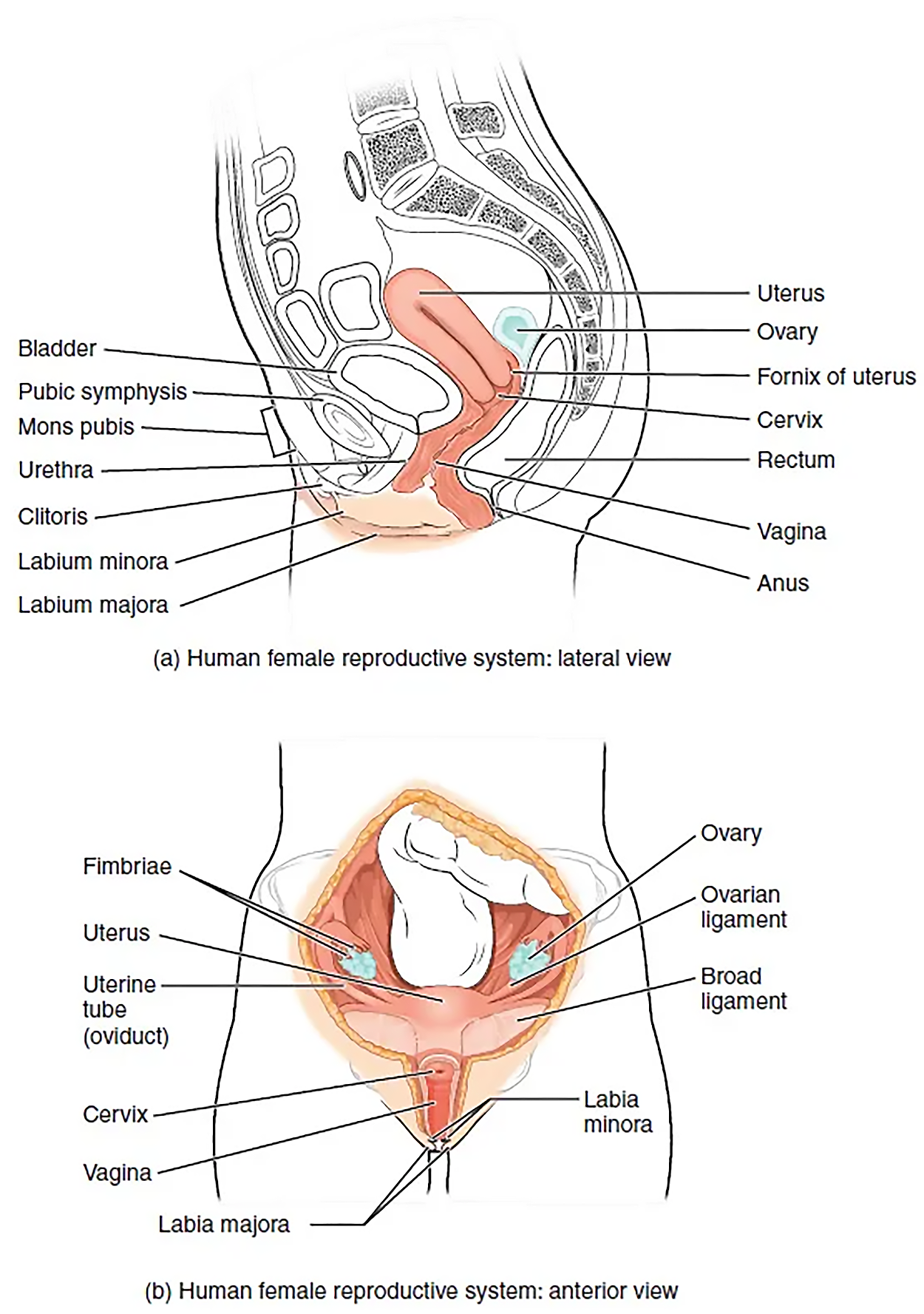

The vagina, shown at the bottom of the image above, is a muscular canal (approximately 10-cm long) that serves as the entrance to the reproductive tract. It also serves as the exit from the uterus during menses (the approximately monthly shedding of the inner portion of the endometrium through the vagina, which you will learn more about in future lessons) and childbirth. The outer walls of the anterior and posterior vagina are formed into longitudinal columns or ridges, and the superior portion of the vagina—called the fornix—meets the protruding uterine cervix. The walls of the vagina are lined with an outer, fibrous adventitia; a middle layer of smooth muscle; and an inner mucous membrane with transverse folds called rugae. Recall that you previously learned that rugae (ruga is singular, rugae is plural) are folds of tissue. Together, the middle and inner layers allow the expansion of the vagina to accommodate intercourse and childbirth. The thin, perforated hymen can partially surround the opening to the vaginal orifice. The hymen can be ruptured with strenuous physical exercise, penile–vaginal intercourse, and childbirth. The greater vestibular glands and the lesser vestibular glands (located near the clitoris) secrete mucus, which keeps the vestibular area moist.

The vagina is home to a normal population of microorganisms that help to protect against infection by pathogenic bacteria, yeast, or other organisms that can enter the vagina. In a healthy person, the most predominant type of vaginal bacteria is from the genus Lactobacillus. This family of beneficial bacterial flora secretes lactic acid and, thus, protects the vagina by maintaining an acidic pH (below 4.5). Potential pathogens are less likely to survive in these acidic conditions.

The uterus is the muscular organ that nourishes and supports a growing embryo (see the image above). Its average size is approximately 5-cm wide by 7-cm long (approximately 2 in by 3 in) when a female is not pregnant. It has three sections. The portion of the uterus superior to the opening of the uterine tubes is called the fundus. The middle section of the uterus is called the body of uterus (or corpus). The cervix is the narrow inferior portion of the uterus that projects into the vagina. The cervix produces mucus secretions that become thin and stringy under the influence of high systemic plasma estrogen concentrations, and these secretions can facilitate sperm movement through the reproductive tract.

Several ligaments maintain the position of the uterus within the abdominopelvic cavity. The broad ligament is a fold of peritoneum that serves as a primary support for the uterus, extending laterally from both sides of the uterus and attaching it to the pelvic wall. The round ligament attaches to the uterus near the uterine tubes and extends to the labia majora. Finally, the uterosacral ligament stabilizes the uterus posteriorly by its connection from the cervix to the pelvic wall.

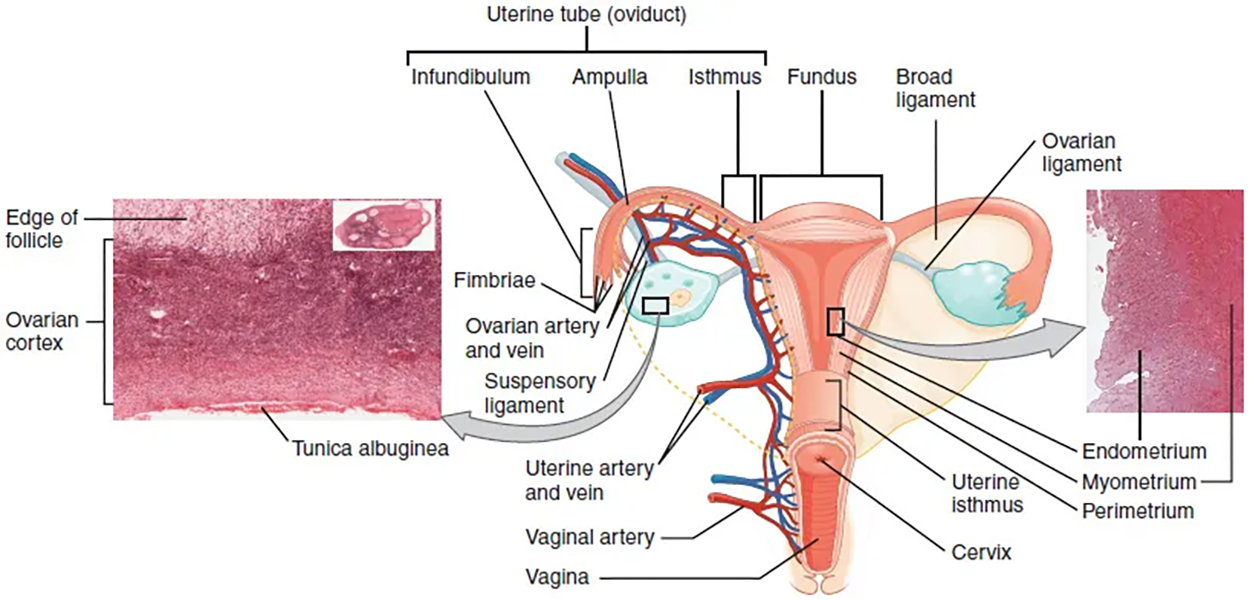

The uterine tubes (also called fallopian tubes or oviducts) serve as the conduit of the oocyte from the ovary to the uterus. Each of the two uterine tubes is close to, but not directly connected to, the ovary and divided into sections. The isthmus (of the uterine tube) is the narrow medial end of each uterine tube that is connected to the uterus. The wide distal infundibulum (of the uterine tube) flares out with slender, finger-like projections called fimbriae. The middle region of the tube, called the ampulla (of the uterine tube), is where fertilization often occurs. The uterine tubes also have three layers: an outer serosa, a middle smooth muscle layer, and an inner mucosal layer. In addition to its mucus-secreting cells, the inner mucosa contains ciliated cells that beat in the direction of the uterus, producing a current that will be critical to move the oocyte.

Following ovulation, the oocyte, surrounded by a few granulosa cells, is released into the peritoneal cavity. The fimbriae of the nearby uterine tube, either left or right, catches the oocyte and sweeps it into the uterine tube.

If the oocyte is successfully fertilized, the resulting zygote will begin to divide into two cells, then four, and so on, as it makes its way through the uterine tube and into the uterus. There, it will implant and continue to grow. If the egg is not fertilized, it will simply degrade—either in the uterine tube or in the uterus, where it may be shed with the next menstrual period.

The open-ended structure of the uterine tubes can have significant health consequences if bacteria or other contagions enter through the vagina and move through the uterus, into the tubes, and then into the pelvic cavity. If this is left unchecked, a bacterial infection (sepsis) could quickly become life-threatening. The spread of an infection in this manner is of special concern when unskilled practitioners perform abortions in non-sterile conditions. Sepsis is also associated with sexually transmitted bacterial infections, especially gonorrhea and chlamydia, which you will learn more about in a future lesson. These increase a person's risk for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which is an infection of the uterine tubes or other reproductive organs. Even when resolved, PID can leave scar tissue in the tubes, leading to infertility.

| Term | Pronunciation | Audio File |

|---|---|---|

| Fimbriae | fim·bria |

|

The ovaries are the female gonads. They produce oocytes as well as substances such as the sex steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone. Paired ovals, they are each about 2 to 3-cm in length, about the size of an almond. The ovaries are located within the pelvic cavity, and are supported by the mesovarium, an extension of the peritoneum that connects the ovaries to the broad ligament. Extending from the mesovarium itself is the suspensory ligament that contains the ovarian blood and lymph vessels. Finally, the ovary itself is attached to the uterus via the ovarian ligament.

The ovary comprises an outer covering of cuboidal epithelium called the ovarian surface epithelium that is superficial to a dense connective tissue covering called the tunica albuginea. Beneath the tunica albuginea is the cortex, or outer portion, of the organ. The cortex is composed of a tissue framework called the ovarian stroma that forms the bulk of the adult ovary. Oocytes develop within the outer layer of this stroma, each surrounded by supporting cells. This grouping of an oocyte and its supporting cells is called a follicle. The growth and development of ovarian follicles will be described shortly. Beneath the cortex lies the inner ovarian medulla, the site of blood vessels, lymph vessels, and the nerves of the ovary.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E" ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL