Table of Contents |

As a reminder, fiscal policy is typically the policy set by a central government authority whereby spending and/or taxation by the government are adjusted to stabilize economic activity.

We know that the government actually has two tools: spending and taxation. Fiscal policy, then, focuses on policies in these two areas. The goal is for the government to use these two tools to stabilize our economy’s movement through business cycles.

It is important to note, though, that there are short-term and long-term goals of fiscal policy.

In the short term, the goals of fiscal policy are full employment and price stability. The government will use taxation and spending to stabilize the economy when either unemployment or inflation rises.

In the long term, though, the goal of fiscal policy is to ensure economic growth, which is the measure of change in real GDP over periods of time. It is usually expressed as a percent change in the value of the sum of goods and services produced in a country’s natural borders over a specified time interval.

Without increasing taxes—because if taxes increase to finance expansionary fiscal policy, this takes money away from people and is thus counterproductive-—the government must borrow money by selling Treasury securities to finance the increased government spending needed to stimulate the economy.

Therefore, the government takes on debt.

To increase demand and stimulate the economy in the short term, the government must spend more money than it collects in tax revenue. It must either increase its government spending or collect fewer taxes, or both, to pump money into the economy and get people spending again.

When these government expenditures exceed tax revenue—which is expansionary fiscal policy—this is known as a deficit. Deficits are shortages that result from spending in excess of revenue.

When the government borrows money to finance the expansionary policy needed, it has two options in the future for debt repayment:

Let’s talk about the second option of debt repayment when the government rolls over its debt and uses new debt to pay off previous debt.

At the very least, it has to pay interest to service the debt. Interest defined is the cost of money. Nominal interest is the prevailing rate. Real interest rates reflect the prevailing rate adjusted for inflation, which means that the real interest rate is the nominal rate minus the inflation rate.

Interest is also a return on investment, where the return varies based on the risk profile of the investment, the time horizon, the opportunity cost of a comparable risk-free investment, and inflation expectations.

As you can see by the definition, there are many different ways in which we can look at interest. Today, we will focus on how interest is the price or cost of money.

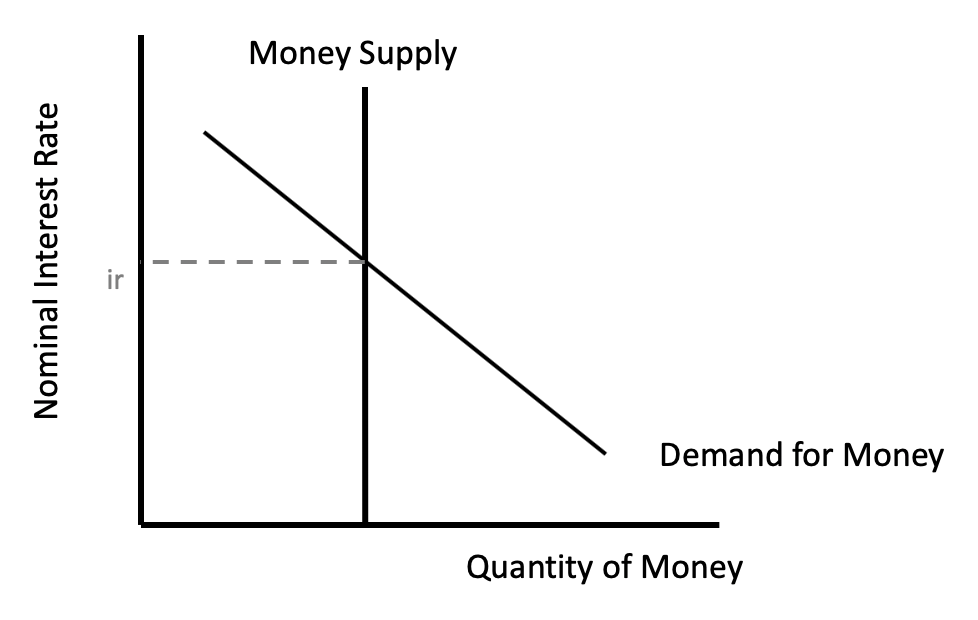

Now, if we look at the money market and a graph of the supply and demand for money, we place the price of money, or the nominal interest rate, on the y-axis and the quantity of money on the x-axis.

We assume that the Fed controls the supply of money, so it is fixed and shown as a vertical line.

The demand for money, though, does vary with interest rates. When interest rates are higher, you would likely prefer to keep your money in the bank instead of spending it, correct? This is because you are earning a higher interest rate on it. In addition, it is more expensive to take out loans.

As rates fall, it is not worth it to keep money in the bank. Now, it is more attractive to take out loans for a home, car, and so forth because the rates are lower.

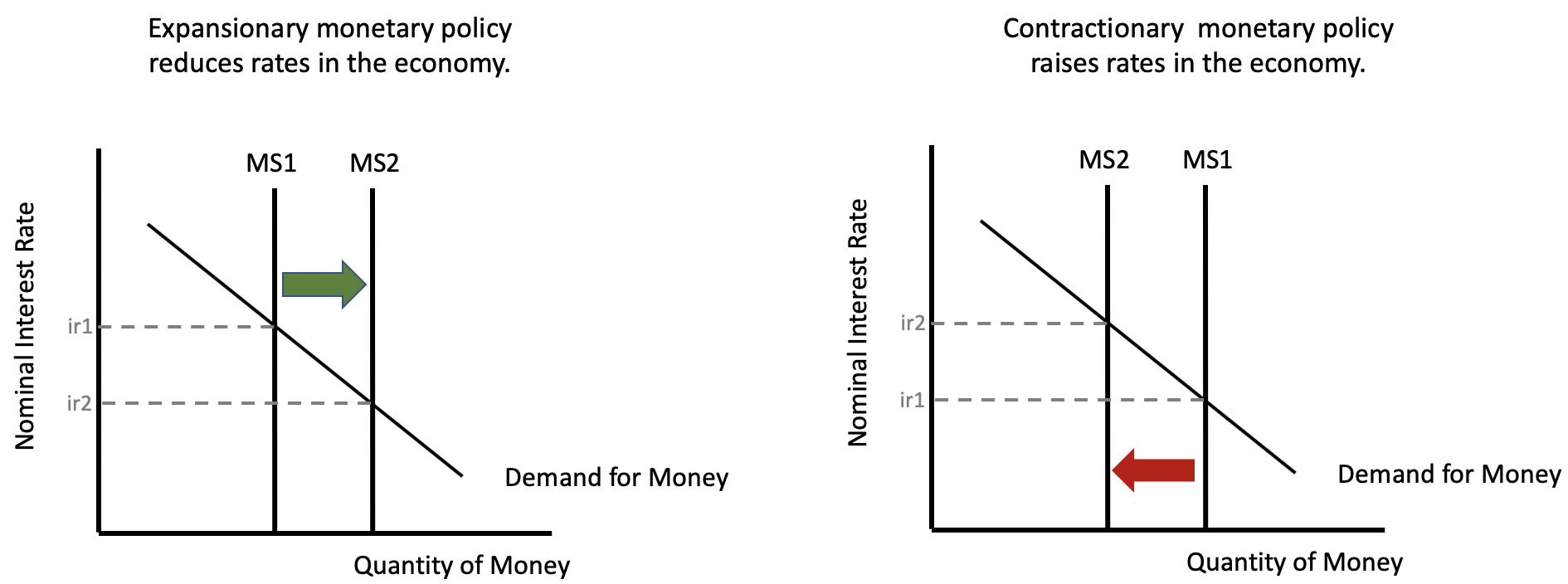

These are two graphs that show that the Federal Reserve can have a direct impact on interest rates by changing the money supply, which is what the Fed controls.

Notice that expansionary monetary policy reduces rates in the economy, while contractionary monetary policy raises rates in the economy.

The Fed can impact interest rates by changing the money supply through its tools: open market operations, the reserve requirement, and targeting rates.

Circling back to the government and fiscal policy, although the government cannot directly influence the money supply, fiscal policy actions can indirectly impact this money market.

The government cannot shift the money supply the way the Fed can. With the government now borrowing money, it becomes an additional demander for loans in an otherwise private market, and when the demand for loans increases, it drives up interest rates.

It is important to keep in mind that when the government is enacting expansionary fiscal policy, the Fed will often do the same and use expansionary monetary policy by either buying Treasury securities or targeting lower rates.

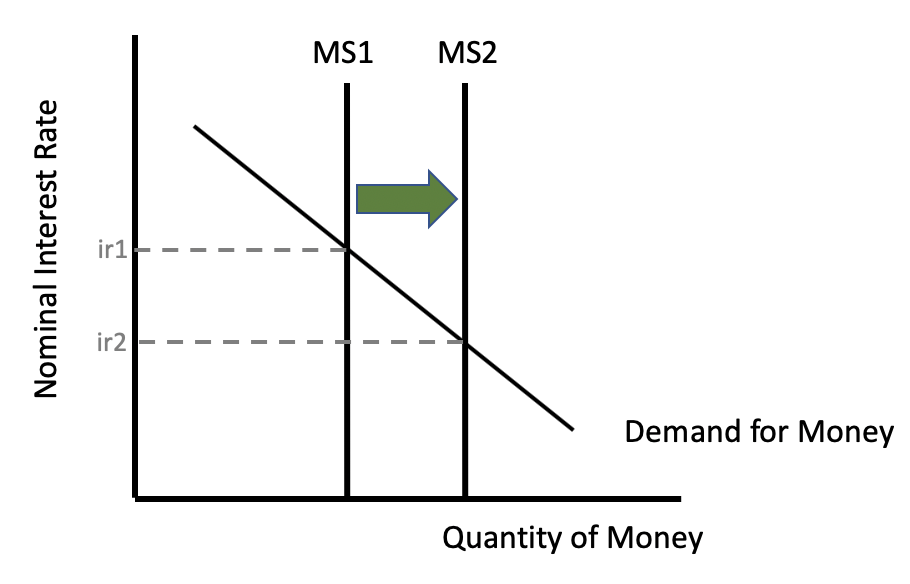

When we increase the money supply, you can see the impact in the graph below.

The effect is to drive rates down, which can offset the impact of the government demanding loans if it is also enacting expansionary monetary policy.

IN CONTEXT

In the recession that followed the housing crisis, it might have been expected that rates would skyrocket as the government borrowed huge sums of money to finance expansionary policies during that crisis.

The government wanted to ensure that our economy did not enter another Great Depression.

Even though it did borrow huge sums of money, rates actually fell for a couple of years. This was because the Fed also took action and enacted major expansionary monetary policy.

Had the Fed not done this, with the government entering the market for loanable funds, rates would have gone up, but because of the Fed’s actions, rates did not rise.

Source: Adapted from Sophia instructor Kate Eskra.