Table of Contents |

Recall that salts are formed when ions form ionic bonds. In these reactions, one atom gives up one or more electrons and thus becomes positively charged; whereas, the other accepts one or more electrons and becomes negatively charged. You can now define a salt as a substance that, when dissolved in water, dissociates into ions other than H⁺ (hydrogen ions) or OH⁻ (hydroxide ions). This fact is important in distinguishing salts from acids and bases.

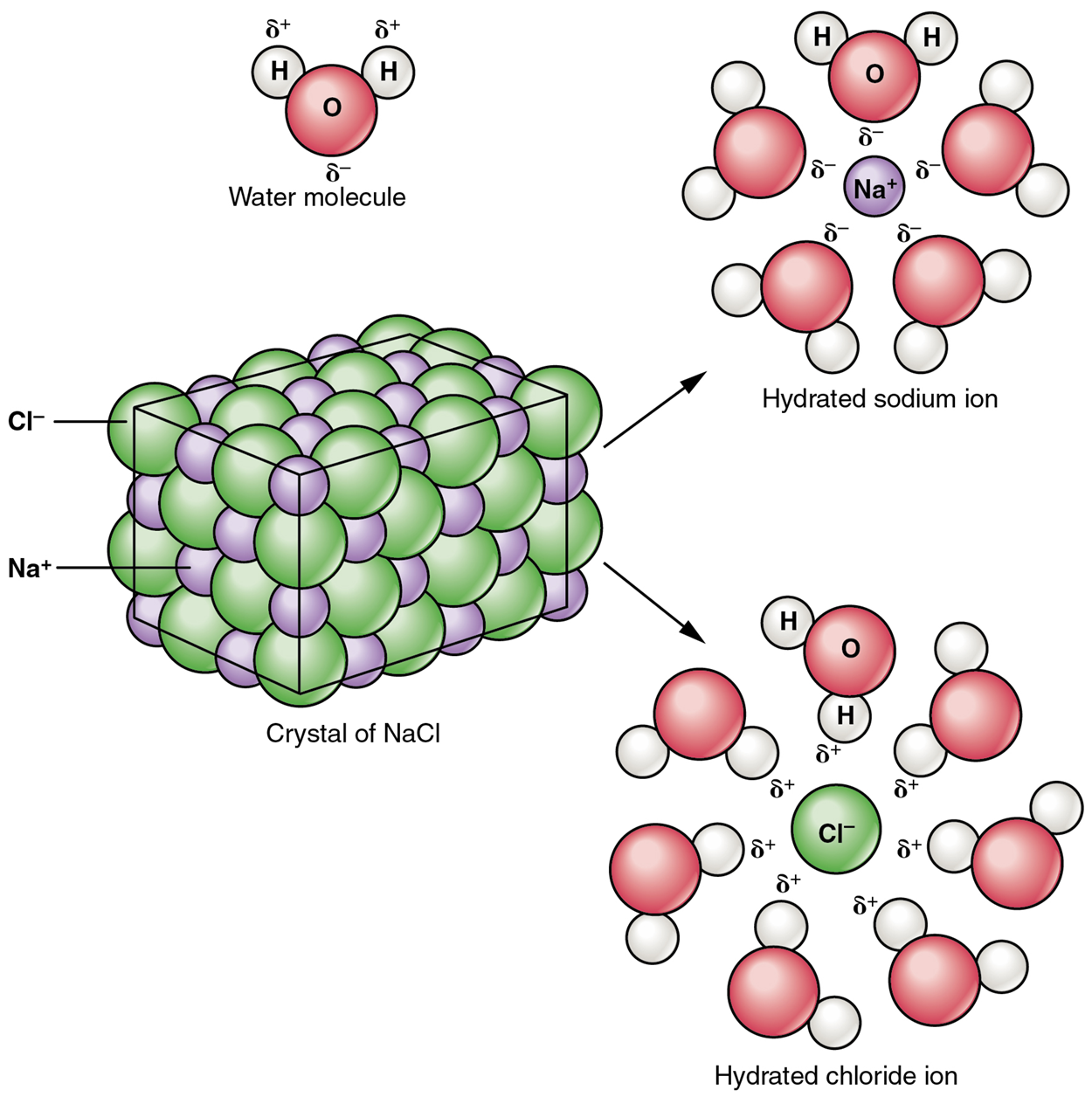

A typical salt, sodium chloride or NaCl, dissociates completely in water as shown in the image below. The partial positive end of the water molecule (the hydrogen atom, H) attracts the negative chloride ion (Cl⁻). The partial negative end of the water molecule (the oxygen atom, O) attracts the positive sodium ion (Na⁺). These attractions overcome the attractive forces of the ionic bond and separate the ions from one another. These ions are electrolytes; they are capable of conducting an electrical current in a solution. This property is critical to the function of ions in transmitting nerve impulses and promoting muscle contraction.

Many other salts are important in the body. For example, bile salts produced by the liver help break apart dietary fats, and calcium phosphate salts form the mineral portion of teeth and bones.

Acids and bases, like salts, dissociate in water into electrolytes. Acids and bases can very much change the properties of the solutions in which they are dissolved.

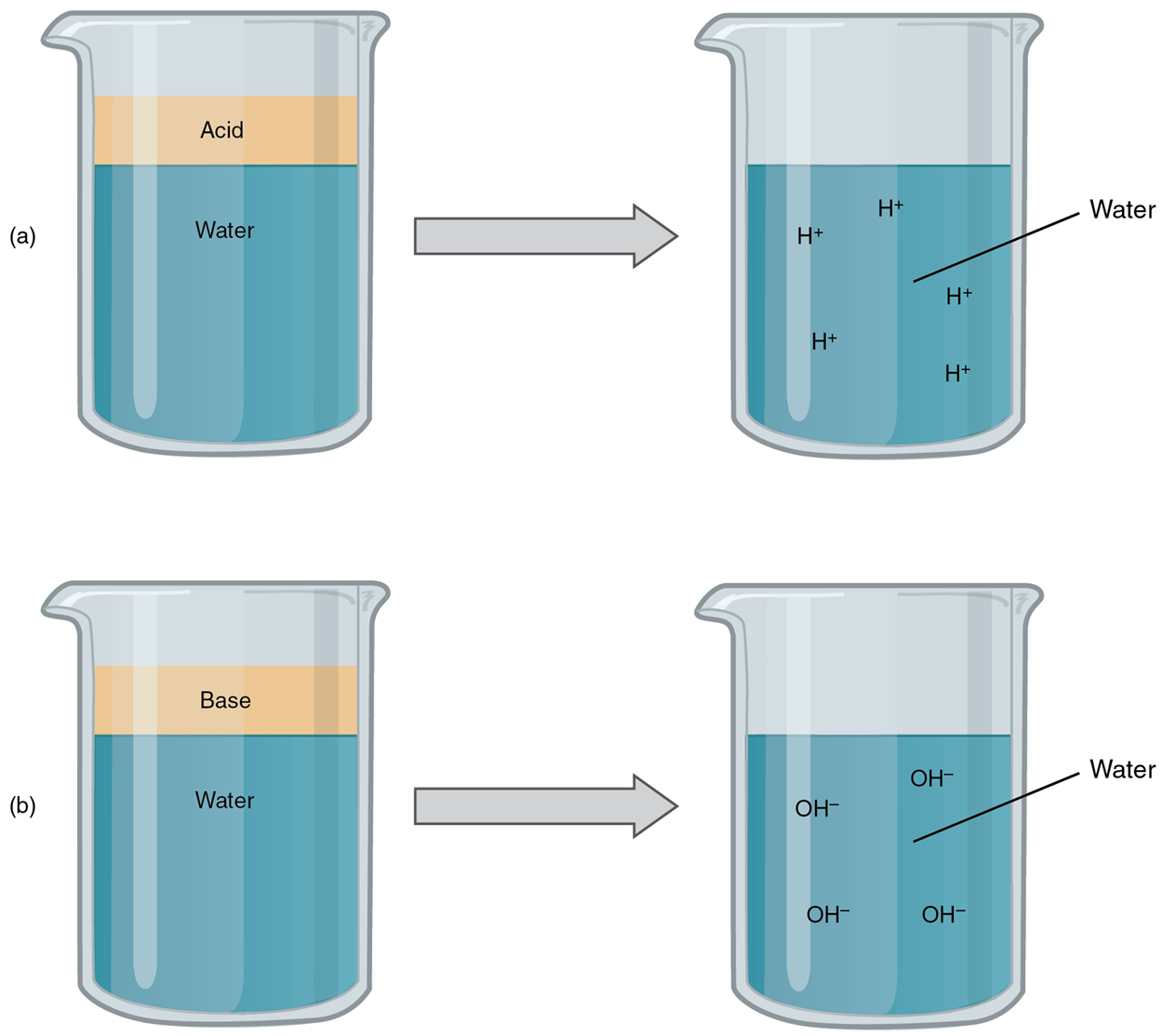

An acid is a substance that releases hydrogen ions (H⁺) in solution. Because an atom of hydrogen has just one proton and one electron, a hydrogen ion, having donated its only electron, is simply a proton. This solitary proton is highly likely to participate in chemical reactions. Acids, or acidic substances, are graded based on how many of their available hydrogen ions they will release in the solution. Strong acids are compounds that release all of their H⁺ in solution; that is, they ionize completely. Weak acids do not ionize completely; that is, some of their hydrogen ions remain bonded within a compound in solution.

EXAMPLE

Hydrochloric acid (HCl), which is released from cells in the lining of the stomach, is a strong acid because it releases all of its H⁺ into the stomach’s watery environment. This strong acid aids in digestion and kills ingested microbes. Vinegar, or acetic acid, is an example of a weak acid and is used commonly in cooking. Weak acids release a much smaller share of their H⁺ ions.

A base is a substance that releases hydroxyl ions (OH⁻) in a solution or one that accepts H⁺ already present in a solution. The hydroxyl ions (also known as hydroxide ions) or other basic substances combine with H⁺ present to form a water molecule, thereby removing a free H+ and reducing the solution’s acidity. Like acids, bases are graded based on the proportion of hydroxyl ions they release or hydrogen ions they accept. Strong bases release most or all of their hydroxyl ions; weak bases release only some hydroxyl ions or absorb only a few H⁺. Bases that dissolve in water are also known as alkali or alkaline substances. Common household alkaline substances include baking soda, soap, ammonia, and bleach.

EXAMPLE

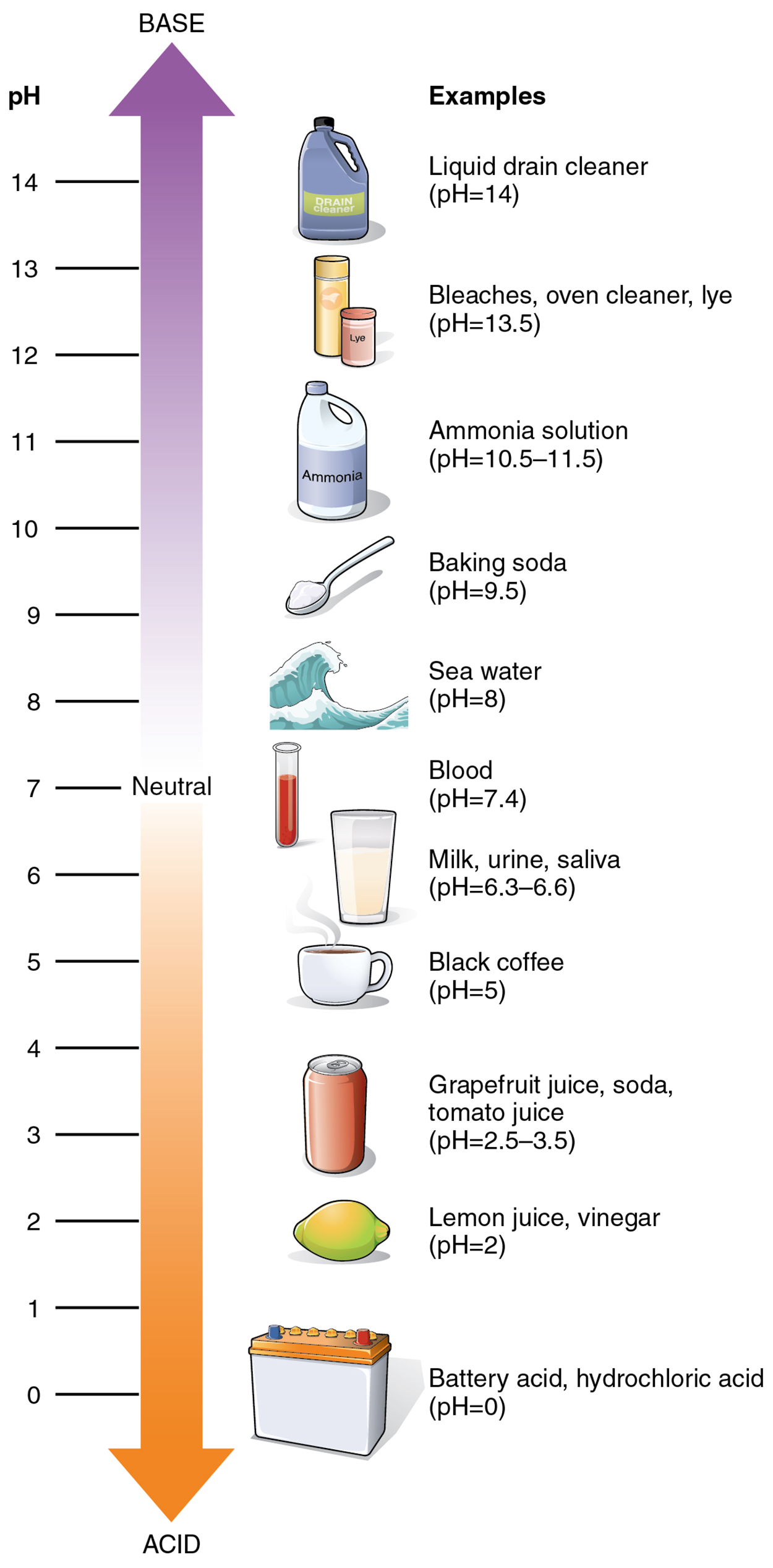

As food mixed with hydrochloric acid (HCl) leaves the stomach, it enters the small intestine. Here, if it were not for the production of bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻), a weak base that attracts H⁺, the food would burn into or through the lining of the small intestine. Bicarbonate accepts some of the H⁺ ions, thereby reducing the acidity of the solution and preserving the lining of the digestive tract.The relative strength of an acid (acidity) or alkali base (alkalinity) in a solution can be indicated by its pH. A solution’s pH is a measure of the hydrogen ion (H⁺) concentration of the solution and can range from 0 to 14. A solution with a pH of 7 is considered neutral—neither acidic nor basic. Pure water has a pH of 7. The lower the number below 7, the more acidic the solution, or the greater the concentration of H⁺. The higher the number above 7, the more basic (alkaline) the solution, or the lower the concentration of H⁺.

The measurement of pH is done on a logarithmic scale. Simply put, a logarithmic scale is used to display a wide range of values in a condensed view where a small change on a logarithmic scale is a much larger difference than you might expect. This means that the difference between whole numbers on the pH scale is a factor of ten and that difference compounds sequentially. As an example, a pH 4 solution has a H⁺ concentration that is ten times greater than that of a pH 5 solution, one-hundred times greater than a pH 6 solution, one thousand times greater than a pH 7 solution, and so forth. Reworded, a pH 4 solution is ten times more acidic than pH 5, 100 times more acidic than pH 6, 1,000 times more acidic than pH 7, and so forth. In context, according to the pH scale shown below, human urine is ten times more acidic than pure water, and hydrochloric acid (HCl) is 10,000,000 times more acidic than water.

The pH of human blood normally ranges from 7.35 to 7.45. At this slightly basic pH, blood can reduce the acidity resulting from the carbon dioxide (CO₂) constantly being released into the bloodstream by the trillions of cells in the body. All cells of the body depend on homeostatic regulatory mechanisms to maintain this acid-base balance within its narrow range. Fluctuations, either too acidic or too alkaline, can lead to life-threatening disorders.

The human body has several homeostatic mechanisms for this regulation you will learn about in future lessons, involving breathing, the excretion of chemicals in urine, and the internal release of chemicals collectively called buffers into body fluids. A buffer is a solution of a weak acid and its conjugate base. A buffer can neutralize small amounts of acids or bases, thereby maintaining the overall pH of the solution. For example, if there is even a slight decrease below 7.35 in the pH of a bodily fluid, the buffer will act as a weak base and bind the excess hydrogen ions. In contrast, if pH rises above 7.45, the buffer will act as a weak acid and contribute hydrogen ions. Both actions work to maintain the overall hydrogen ion (H⁺) concentration (aka, pH) of the blood.

Fluctuations outside of this narrow blood pH range do occur, however. Excessive acidity of the blood and other body fluids is known as acidosis. The cause of acidosis is generally a buildup of CO₂ in the body due to excessive CO₂ production and/or limited removal or buffering. Excessive alkalinity of the blood and other body fluids is known as alkalosis. The general cause of alkalosis is a decrease of CO₂ in the blood due to decreased production and/or excessive removal. Both states can also be the result of underlying diseases, oral medications, and more.

Source: THIS CONTENT HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E" AT openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e