Table of Contents |

The nervous system and the endocrine system work together to control body functions. The nervous system detects information, such as a painful stimulus, and responds in some way.

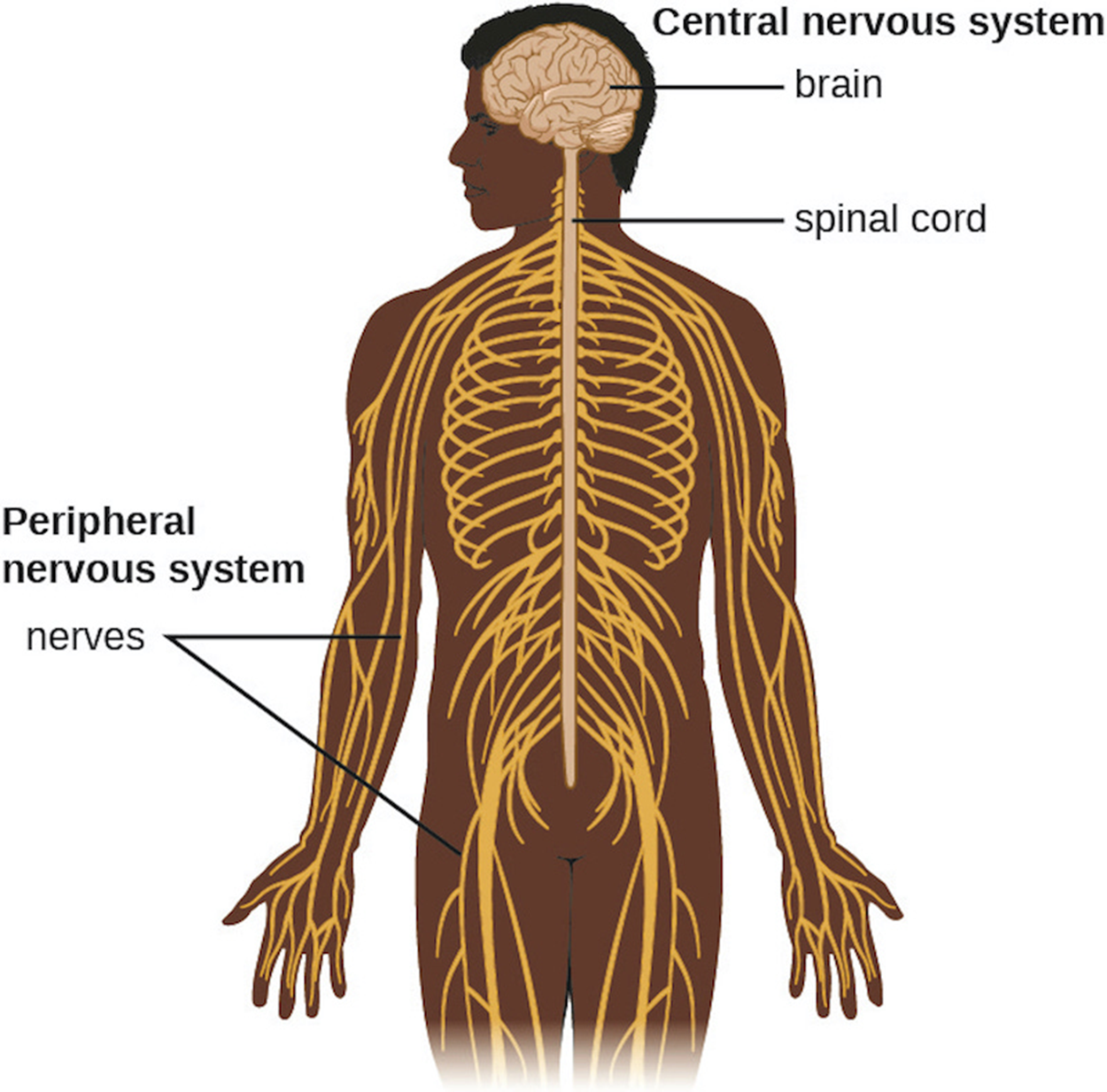

The human nervous system can be divided into two major components: the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS includes the brain and spinal cord whereas the PNS includes all other components of the nervous system. These two systems are illustrated in the image below, which shows how the PNS extends from the CNS to the extremities (arms and legs).

The brain is a complex organ responsible for receiving impulses, responding to stimuli, remembering information, interpreting sensory information, integrating information, and complex thinking. In vertebrate animals, it is protected by a bony cranium or skull. Although the skull provides a hard covering that shields the brain from damage, it also means that swelling, fluid build-up, and growth (such as cancer) can put pressure on the brain as there is no room for expansion and this can potentially lead to brain damage.

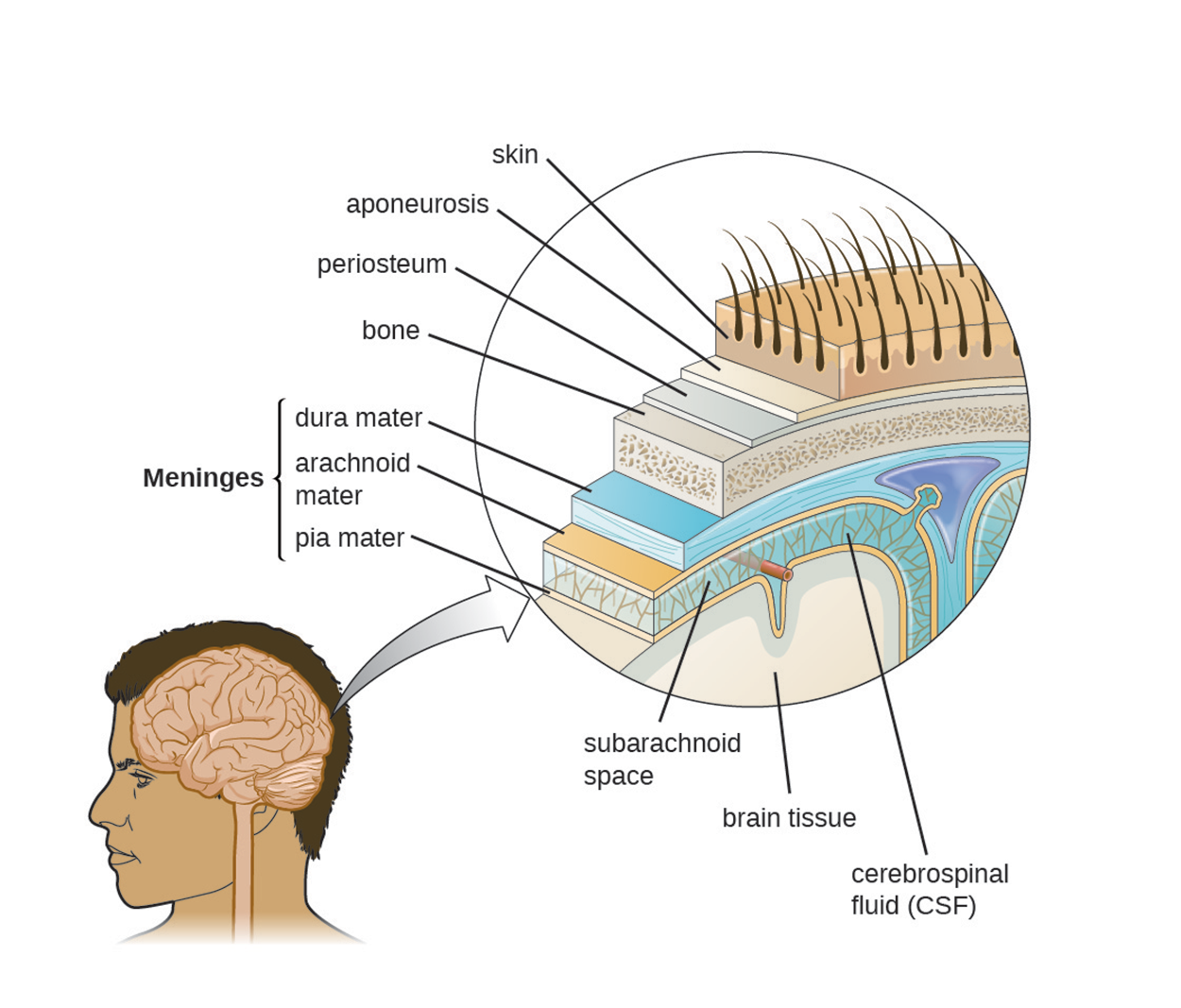

As shown in the image below, there is skin covering the skull that is attached by a broad connective tissue layer called the aponeurosis. Immediately below the aponeurosis, there is a membranous periosteum that provides protection and nutrition to the bone in addition to aiding bone repair. Below the periosteum, mammals have three layers of membranes called meninges (singular meninx) surrounding the brain and spinal cord. From outermost to innermost, these layers are the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater. The pia mater adheres to the surface of the brain. The subarachnoid space, located between the arachnoid mater and pia mater, is filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF is found in the spinal cord as well and is a watery fluid produced by cells of the choroid plexus (regions of cells surrounding dense capillary beds in open regions of the brain called ventricles). The CSF transports dissolved substances, delivering nutrients and removing waste.

The brain is somewhat isolated from the substances in blood in the rest of the body by the blood–brain barrier. Blood vessels that supply the brain are located above the pia mater. Among other features, the capillaries in this region are less permeable than other capillaries of the body. This allows for tight control over what can travel through these capillary walls into the brain.

The blood–brain barrier protects the CSF from contamination and prevents microbes from entering the CNS. The CSF also has no normal microbiota. An additional consequence of this barrier is that substances such as medications may not easily enter the brain to treat infections there. A similar barrier, the blood–spinal cord barrier, provides a similar function for the spinal cord.

To cause an infection in the CNS, pathogens must cross the blood–brain or blood–spinal cord barrier. The four major ways in which pathogens accomplish this are as follows:

The nervous system contains two major types of cells: neurons that conduct impulses and glial cells (also called neuroglial cells) that perform supportive functions. Neurons vary in structure but have a cell body, finely branched protrusions called dendrites that pick up incoming impulses, and a long axon that carries impulses to another neuron or other cell (such as a muscle cell). Axons are often covered with a substance called myelin to form a myelin sheath, which makes impulse transmission more rapid. The myelin sheath is produced by glial cells (Schwann cells in the PNS and oligodendrocytes in the CNS).

In the PNS, a bundle of axons is called a nerve. In some cases, including this one, terminology differs between the CNS and PNS. A bundle of axons in the CNS is called a tract.

Neurons form junctions with other cells with which they exchange signals. These junctions are called synapses and there is a space called a synaptic cleft between them. Neurotransmitters can be released from the terminal of one axon and travel across the synapse to bind to receptors of the next cell to stimulate it.

As already mentioned, a variety of diseases and disorders can affect the nervous system. Some general terms can be used regardless of the cause of the condition. The following are particularly important terms to know:

In the rest of this lesson, you will learn about examples of some types of nervous system infections caused by bacteria, acellular agents, fungi, and protozoa.

Bacterial infections that affect the nervous system can be serious and life-threatening. However, relatively few bacterial species are associated with neurological infections.

Meningitis can have multiple causes, as discussed above, and meningitis caused by bacteria (bacterial meningitis) is particularly serious. Bacteria often gain access to the CNS through the bloodstream after trauma or as a result of the action of bacterial toxins. Bacteria may also spread from the structures in the upper respiratory tract. The most common (but not only) causes of bacterial meningitis are Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae. All three of these species spread from person to person through respiratory secretions and can cross mucous membranes of the nasopharynx and oropharynx to enter the blood and disseminate in the body. The case fatality rate can be as high as 70% without appropriate treatment, but therapeutic drugs and preventive vaccines are available.

Meningococcal meningitis is a serious infection caused by N. meningitidis. It can potentially cause death within hours. Outbreaks and epidemics can occur, but meningococcal vaccines lower the risk. Individuals most at risk of developing meningococcal meningitis are those who have regular close physical contact with others in locations such as prisons, schools, and colleges.

H. influenzae type b can be the primary cause of meningitis in individuals aged 2 months to 5 years, but it is less common in many regions since the introduction of the Hib vaccine.

Pneumococcal meningitis is caused by S. pneumoniae. It is sometimes present without causing disease symptoms but can cross the blood–brain barrier in susceptible individuals. Since the introduction of a vaccine to prevent infection by H. influenzae type b, this is now the most common cause of meningitis in individuals older than 2 years.

Neonatal meningitis can have multiple causes but most commonly results from infection by S. agalactiae (a group B Streptococcus). Early onset disease occurs within the first seven days of life and late onset disease occurs between one and three months of age. Infants can become infected during childbirth, so antibiotic treatment of the mother during labor can reduce the risk.

Tetanus is caused by Clostridium tetani, which can enter a wound and produce tetanus toxin. This toxin causes uncontrollable muscle spasms and can lead to death. Tetanus can be localized (affecting only muscles near the injury), cephalic (generally associated with wounds of the head or face), or generalized (having systemic effects). Systemic tetanus is the most dangerous. Neonatal tetanus is a dangerous form of tetanus that is generally caused by contamination of the umbilical cord stump after delivery, meaning that it is most common when conditions are unsanitary. A tetanus toxoid vaccine is available to prevent tetanus and is included in several vaccines (summarized in the table at the end of this section).

Botulism is a rare but frequently fatal illness caused by a toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum. Forms include wound botulism, infant botulism, and adult intestinal toxemia. Wound botulism results when a wound is contaminated. Both infant botulism and adult intestinal toxemia result from ingestion of contaminated food. Some foods, such as honey, pose particular risks for infants (CDC, 2022c).

The table below provides an overview of these and other bacterial infections of the nervous system.

| Bacterial Infections of the Nervous System | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Pathogen | Signs and Symptoms | Transmission | Vaccine |

| Botulism | C. botulinum | Blurred vision, drooping eyelids, difficulty swallowing and breathing, nausea, vomiting, often fatal | Ingestion of preformed toxin in food, ingestion of endospores in food by infants or immuno- compromised adults, bacterium introduced via wound or injection | None |

| Hansen's disease (leprosy) | Mycobacterium leprae | Hypopigmented skin, skin lesions, and nodules, loss of peripheral nerve function, loss of fingers, toes, and extremities | Inhalation, possibly transmissible from armadillos to humans | None |

| H. influenzae type b meningitis | H. influenzae | Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, stiff neck, confusion | Direct contact, inhalation of aerosols | Hib vaccine |

| Listeriosis | Listeria monocytogenes | Initial flu-like symptoms, sepsis and potentially fatal meningitis in susceptible individuals, miscarriage in pregnant women | Bacterium ingested with contaminated food or water | None |

| Meningococcal meningitis | N. meningitidis | Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, stiff neck, confusion, often fatal | Direct contact | Meningococcal conjugate |

| Neonatal meningitis | Streptococcus agalactiae | Temperature instability, apnea, bradycardia, hypotension, feeding difficulty, irritability, limpness, seizures, bulging fontanel, stiff neck, opisthotonos (a type of muscle spasm), hemiparesis (paralysis of a single side of the body), often fatal | Direct contact in birth canal | None |

| Pneumococcal meningitis | S. pneumoniae | Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, stiff neck, confusion; often fatal | Direct contact, aerosols | Pneumococcal vaccines |

| Tetanus | C. tetani | Progressive spasmatic paralysis starting with the jaw, often fatal | Bacterium introduced in puncture wound | DTaP, Tdap |

Viruses and other acellular agents can also cause nervous system infections of various levels of severity. Although more common compared with bacterial infections of the nervous system, viral infections tend to be milder and often spontaneously resolve.

Many types of viruses can produce viral meningitis, which is typically less severe than bacterial meningitis. Viral meningitis sometimes follows a primary infection caused by a virus such as influenza or herpes.

Several types of encephalitis are caused by insect-borne viruses, and these are collectively called arboviral encephalitis. Mosquitoes are common vectors. Most arboviruses are endemic to specific geographic regions. Although they generally cause relatively mild disease, infections can potentially be serious or even fatal (especially in the elderly). In the United States, examples include eastern equine encephalitis, western equine encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis, and West Nile encephalitis.

Zika virus infection is an emerging arboviral disease that can potentially cause severe adverse effects in developing fetuses. From 2013 to 2016, outbreaks occurred around the world that led to the realization that Zika was dangerous to fetuses (causing issues with cranial development), leading to questions about why this had not been recognized earlier that may aid in identifying similar risks more quickly in other emerging diseases (Gilbert et al., 2022).

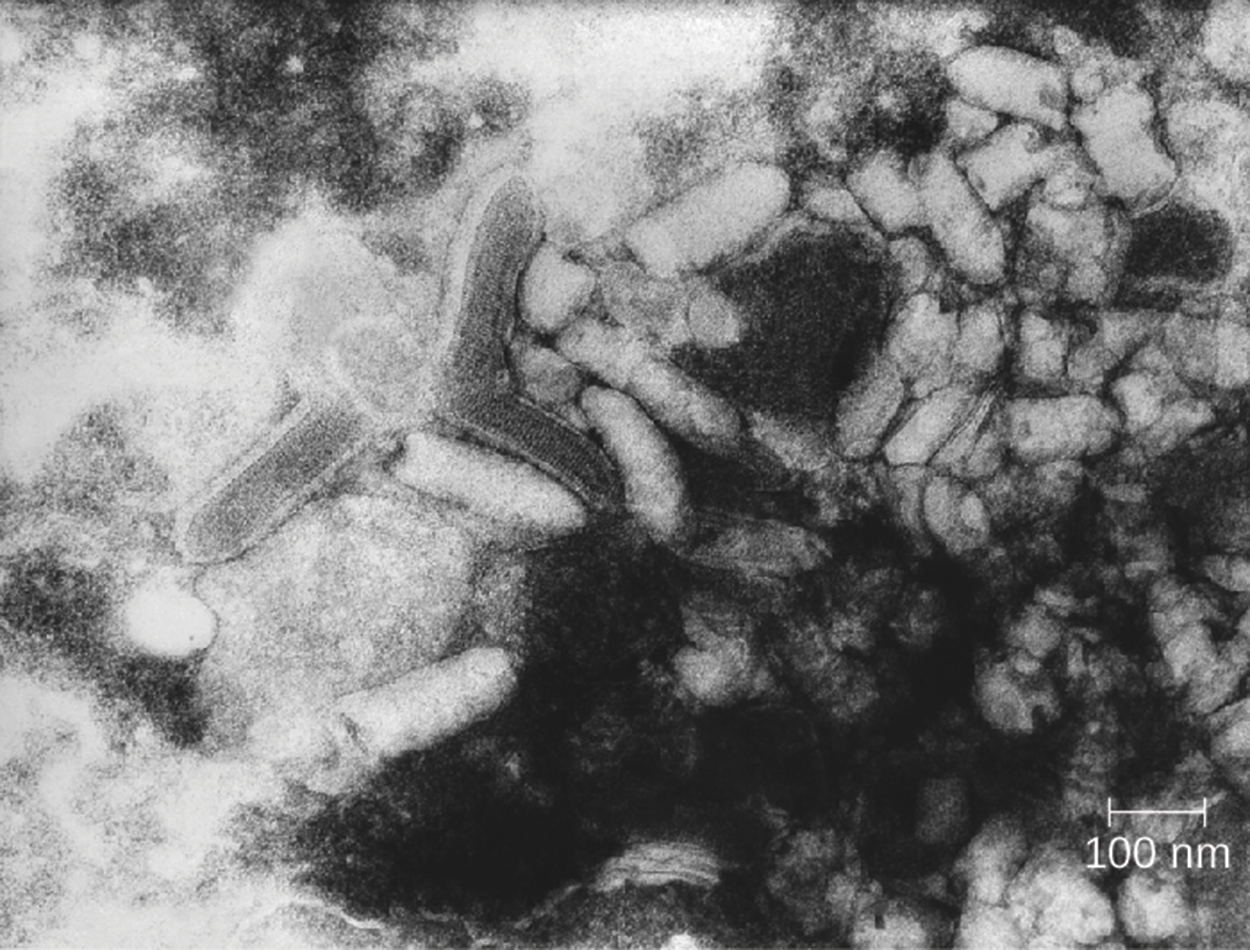

Rabies is a well-known zoonotic disease that is caused by the rabies virus and is transmitted primarily through the bite of an infected animal. Some types of animals (such as racoons and bats) are much more likely to serve as reservoirs for the virus than others. Vaccination of dogs and cats helps prevent cases in humans. The incubation period can be relatively long. Early symptoms include discomfort at the site of the bite, fever, and headache. Once the brain is affected and neurological symptoms appear, the disease is almost always fatal with only a few known exceptional cases (WHO, 2023). If humans are potentially exposed, prophylactic treatment can prevent infection. The micrograph below shows virions of the rabies virus.

Poliomyelitis (polio) is caused by a poliovirus and can sometimes progress from an intestinal infection to infect the CNS. When it infects the CNS, it can cause paralysis and potentially death. Vaccination has made polio uncommon in most parts of the world, but it is still endemic in some countries despite continued efforts to eradicate it.

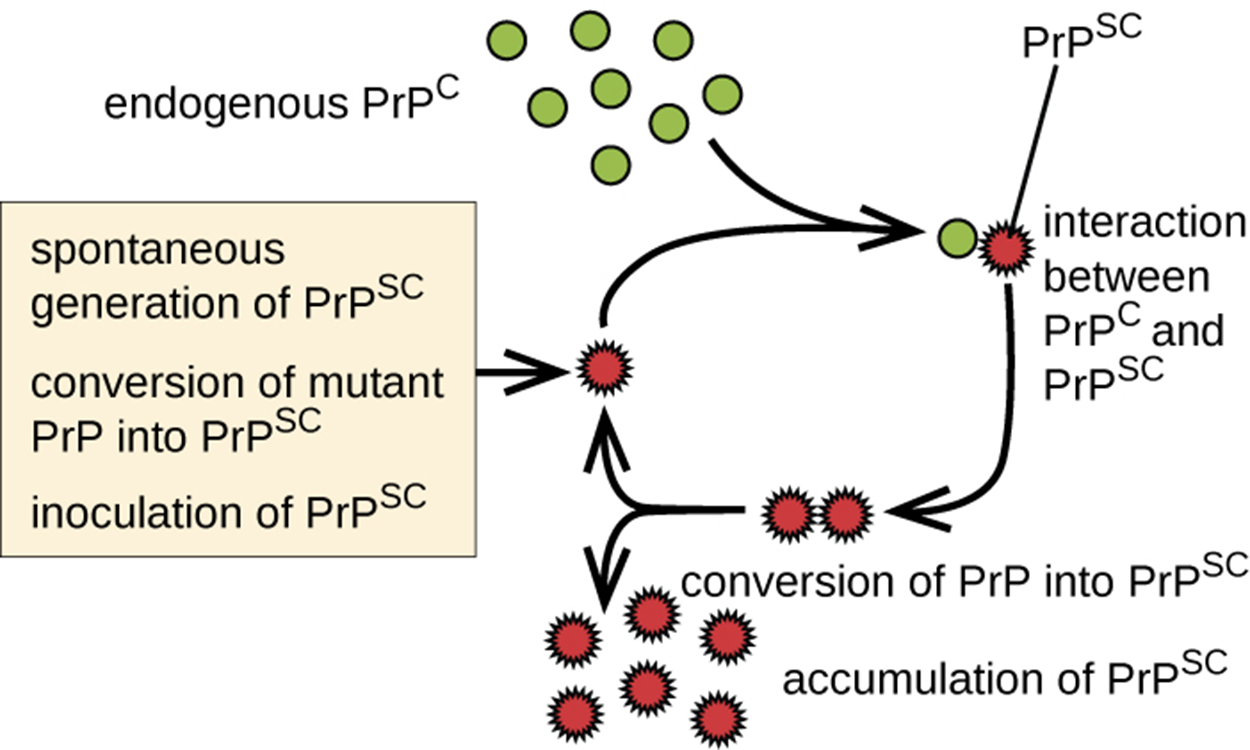

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) are caused by prions, not viruses. TSEs are all degenerative, fatal neurological diseases with a slow onset. Prions consist only of protein. These are similar to proteins normally found in the nervous system but are folded abnormally and can cause other proteins to become similarly deformed. As shown by the illustration below, a normal protein ( ) can spontaneously convert into a mutant protein (

) can spontaneously convert into a mutant protein ( ) or

) or  can be introduced from elsewhere.

can be introduced from elsewhere.  interacts with

interacts with  to convert it.

to convert it.

As  accumulates, it aggregates and forms fibrils in nerve cells that ultimately cause the cells to die. As a consequence, the brain develops a spongy appearance.

accumulates, it aggregates and forms fibrils in nerve cells that ultimately cause the cells to die. As a consequence, the brain develops a spongy appearance.

EXAMPLE

TSEs in animals include scrapie (a disease in sheep), chronic wasting disease (a disease of deer and elk), and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (also called mad cow disease and found in cows). Human TSEs include Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and kuru. All of these diseases produce CNS symptoms and are contracted by encountering deformed prions.The table below summarizes acellular infections of the nervous system.

| Acellular Infections of the Nervous System | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Pathogen | Signs and Symptoms | Transmission | Diagnostic Tests | Vaccine |

| Arboviral encephalitis (eastern equine, western equine, St. Louis, West Nile, Japanese) | EEEV, WEEV, SLEV, WNV, JEV | In mild cases, fever, chills, headaches, and restlessness; in serious cases, encephalitis leading to convulsions, coma, and death | From bird reservoirs to humans (and horses) by mosquito vectors of various species | Serologic testing of serum or CSF | Human vaccine available for JEV only; no vaccines available for other arboviruses |

| Creutzfeldt–Jacob Disease and other TSEs | Prions | Memory loss, confusion, blurred vision, uncoordinated movement, insomnia, coma, death | Exposure to infected nerve tissue via consumption or transplant, inherited | Tissue biopsy | None |

| Poliomyelitis | Poliovirus | Asymptomatic or mild nausea, fever, headache in most cases; in neurological infections, flaccid paralysis and potentially fatal respiratory paralysis | Fecal–oral route or contact with droplets or aerosols | Culture of poliovirus, PCR | Attenuated vaccine (Sabin), killed vaccine (Salk) |

| Rabies | Rabies virus (RV) | Fever, headaches, hyperactivity, hydrophobia, excessive salivation, terrors, confusion, spreading paralysis, coma, always fatal if not promptly treated | From bite of infected mammal | Viral antigen in tissue, antibodies to virus | Attenuated vaccine |

| Viral meningitis | HSV-1, HSV-2, varicella zoster virus, mumps virus, influenza virus, measles virus | Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, stiff neck, confusion, symptoms generally resolve within 7–10 days | Sequela of primary viral infection | Testing of oral, fecal, blood, or CSF samples | Varies depending on cause |

| Zika virus infection | Zika virus | Fever, rash, conjunctivitis; in pregnant women, can cause fetal brain damage and microcephaly (a small head) | Between humans by Aedes spp. mosquito vectors, also may be transmitted sexually or via blood transfusion | Zika virus RNA assay, Trioplex RT-PCR, Zika MAC-ELISA test | None |

A variety of fungi can cause nervous system diseases, and these are called neuromycoses. These are rare in healthy individuals but can be very dangerous in individuals who are elderly or immunocompromised.

Cryptococcal meningitis is a type of meningitis caused by a fungal pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans. This fungus is commonly found in soils and is particularly associated with pigeon droppings. Cases are usually subclinical in healthy individuals but can be serious.

The table below shows examples of additional neuromycoses.

| Neuromycoses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Pathogen | Signs and Symptoms | Transmission | Diagnostic Tests |

| Aspergillosis | Aspergillus fumigatus | Meningitis, brain abscesses | Dissemination from respiratory infection | CSF, routine culture |

| Candidiasis | Candida albicans | Meningitis | Oropharynx or urogenital | CSF, routine culture |

| Coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) | Coccidioides immitis | Meningitis (in about 1% of infections) | Dissemination from respiratory infection | CSF, routine culture |

| Cryptococcosis | C. neoformans | Meningitis, granuloma formation in brain | Inhalation | Negative stain of CSF, routine culture |

| Histoplasmosis | Histoplasma capsulatum | Meningitis, granulomas in the brain | Dissemination from respiratory infection | CSF, routine culture |

| Mucormycosis | Rhizopus arrhizus | Brain abscess | Nasopharynx | CSF, routine culture |

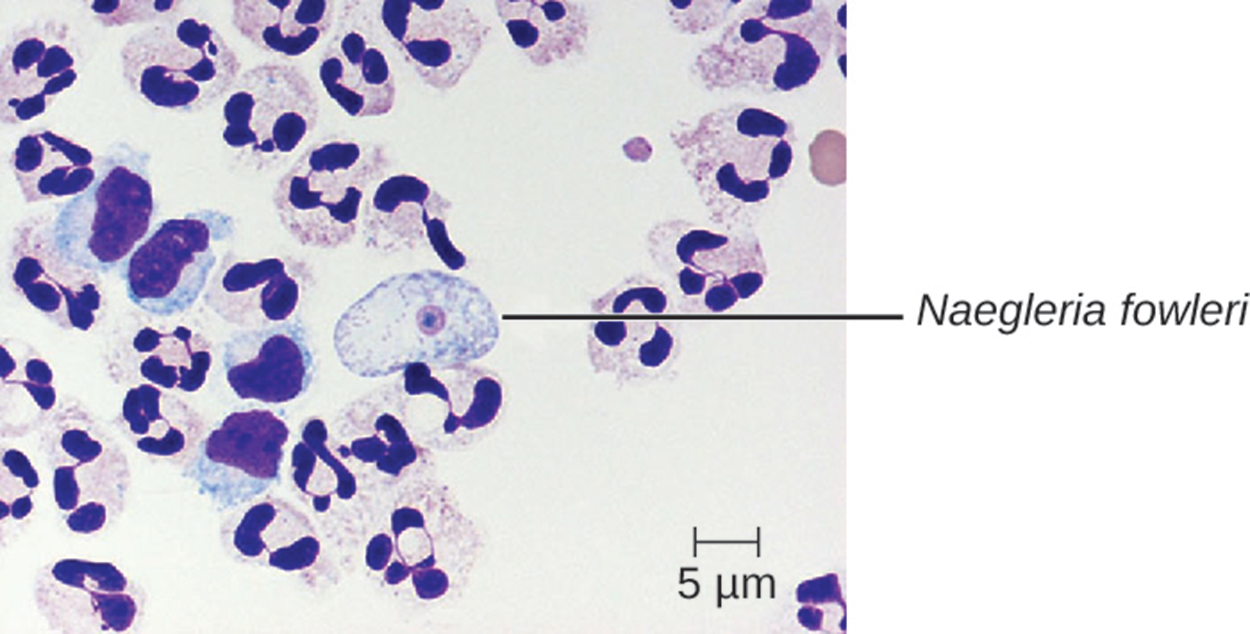

Protozoa can also cause neurological infections. One of the most infamous examples is the so-called “brain-eating amoeba,” which is actually Naegleria fowleri. This organism lives in soil and water and is only infective in its trophozoite form (the part of its life cycle during which it is actively feeding and growing). It most commonly accesses the brain by entering the nose in contaminated water and is most abundant in warm, freshwater bodies such as lakes. The pathogen travels through the nasal passages to the sinuses, then moves down olfactory nerve fibers. After passing through several additional structures, it makes its way to the subarachnoid space. From the subarachnoid space, it can disseminate into other parts of the CNS including the brain. Inflammation and destruction of gray matter leads to severe headaches and fever. Disease progression is rapid and almost always lethal. This disease is called primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM).

The micrograph below shows N. fowleri in human brain tissue.

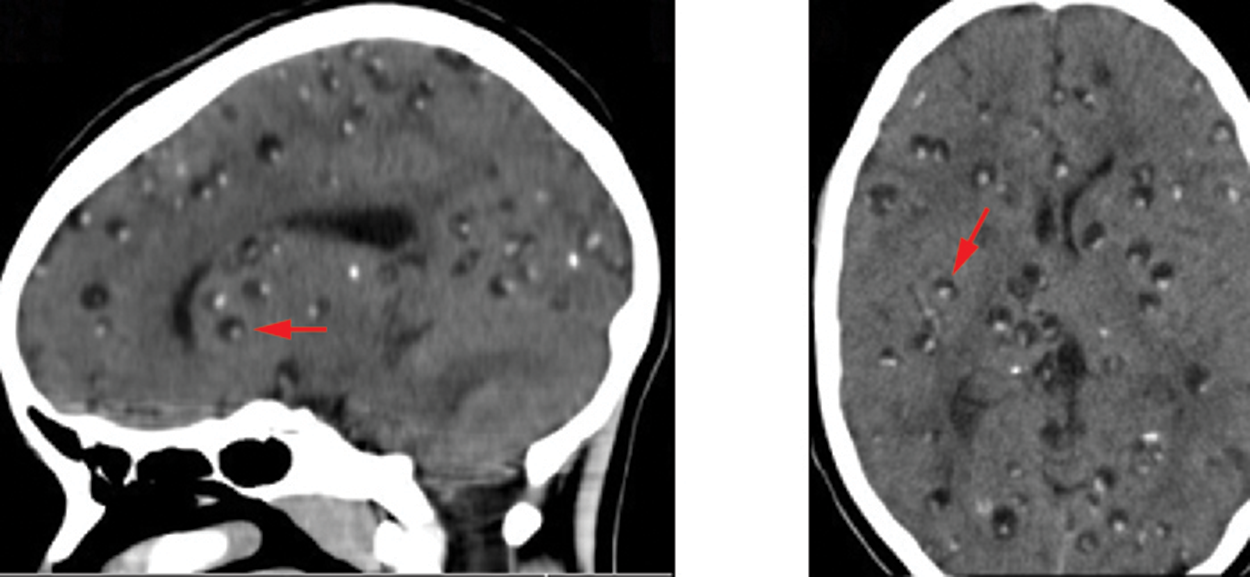

As mentioned in the lesson on digestive tract infections, pork tapeworm eggs can hatch in the digestive tract and spread into other parts of the body to form cysts. Neurocysticerci are larval cysts in brain tissue, as indicated by arrows in the images below.

The table below provides descriptions of these and additional examples of parasitic diseases of the nervous system.

| Parasitic Diseases of the Nervous System | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Pathogen | Signs and Symptoms | Transmission | Diagnostic Tests |

| Granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE) | Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris | Inflammation, lesions in CNS, almost always fatal | Freshwater amoebae invade CNS via breaks in skin or sinuses | CT scan, MRI, CSF |

| Human African trypanosomiasis | Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, T. b. rhodesiense | Chancre, Winterbottom's sign (a pattern of lymph node swelling), undulating fever, lethargy, insomnia, usually fatal if untreated | Protozoan transmitted via bite of tsetse fly | Blood smear |

| Neurocysticercosis | Taenia solium | Brain cysts, epilepsy | Ingestion of tapeworm eggs in fecally contaminated food or surfaces | CT scan, MRI |

| Neurotoxoplasmosis | Toxoplasma gondii | Brain abscesses, chronic encephalitis | Protozoan transmitted via contact with oocytes in cat feces | CT scan, MRI, CSF |

| Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) | N. fowleri | Headache, seizures, coma, almost always fatal | Freshwater amoebae invade brain via nasal passages | CSF, IFA, PCR |

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT openstax.org/details/books/microbiology. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

BBC. (1999). BSE inquiry. Retrieved January 17, 2023, from news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/special_report/1999/06/99/bse_inquiry/default.stm

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2022a). Retrieved January 17, 2023, from www.cdc.gov/tetanus/index.html

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2022b). Surveillance. Retrieved January 17, 2023, from www.cdc.gov/tetanus/surveillance.html

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2022c). Botulism prevention. Retrieved January 15, 2023, from www.cdc.gov/botulism/prevention.html

Gilbert, R. K., Petersen, L. R., Honein, M. A., Moore, C. A., & Rasmussen, S. A. (2022). Zika virus as a cause of birth defects: Were the teratogenic effects of Zika virus missed for decades?. Birth defects research, 10.1002/bdr2.2134. Advance online publication. doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.2134

World Health Organization. (2023). Rabies. Retrieved January 15, 2023, from www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies