Table of Contents |

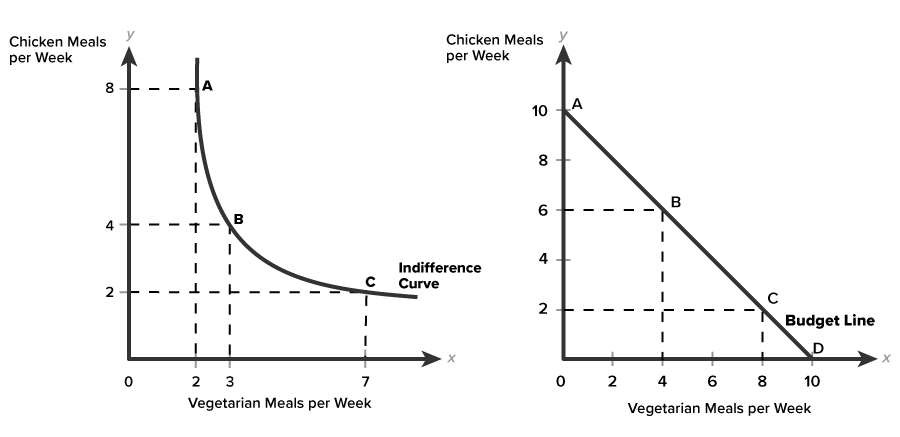

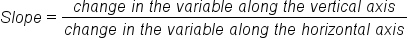

Indifference curves and budget lines illustrate the trade-offs between two goods or services we face as we consider making small changes in our choices. The following is an example of an indifference curve and a budget line.

Let’s use the indifference curve diagram above to calculate opportunity cost, the value of what is given up to get something else, moving from point to point along the curve.

Start at point A on the indifference curve, where the consumer has 8 chicken meals and 2 vegetarian meals and move down the curve to calculate the opportunity cost:

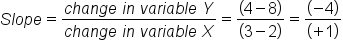

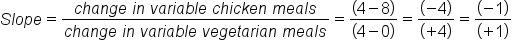

The following slope formula shows the opportunity cost of moving down along the indifference curve.

Both the indifference curve and the budget line have slope. You can use the slope formula to calculate the opportunity cost at any two points along either the indifference curve or the budget line.

In economics, the slope of the indifference curve is known as the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) between the two possible choices made between chicken and vegetarian meals. The slope of the budget line is known as the marginal rate of transformation (MRT) between the quantities of the two priced goods.

In economics, the slope is interpreted as the opportunity cost a decision maker faces when choosing between two alternative actions. The slope of the indifference curve is the marginal rate of substitution (MRS). The MRS identifies the sacrifices a person is willing to make between two goods. The slope of the budget line is the marginal rate of transformation (MRT). The MRT identifies the quantity of some good that must be sacrificed to acquire one additional unit of the other good.

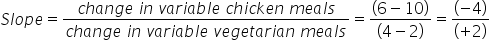

We can use the slope formula to calculate the slope of the indifference curve (MRS) starting at point A and moving to B. As you can see, we give up 4 chicken meals and get 2 additional vegetarian meal per week.

Interpretation: The cost of one additional vegetarian meal is 4 chicken meals per week. We can use the slope formula to calculate the slope of the budget line starting at point A and moving to B. As you can see, the cost involves giving up 4 chicken meals in order to get 4 additional vegetarian meals per week.

Interpretation: The cost of an additional vegetarian meal is 1 chicken meal per week.

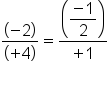

You can use the slope formula to calculate the slope at any point along either line. In the calculations table below, notice that the slope along the straight budget line is constant. It is the same at every point: give up one chicken meal to get one additional vegetarian meal per week.

| A to B |

|

| B to C |

|

| C to D |

|

Unlike the budget line, the slope is not constant for the indifference curve, as shown in the calculations table below. At the top of the curve, we are willing to trade four chicken meals to get one additional vegetarian meal. At the bottom of the curve we are only willing to trade half of a chicken meal to get one additional vegetarian meal per week.

| A to B |

|

| B to C |

|

Take another look at the indifference curve in the graph above. Notice that as you move down along the indifference curve, it becomes flatter or more horizontal. It seems that our enthusiasm for trading off chicken meals declines as we move down along the indifference curve. And that is perfectly reasonable because we have fewer and fewer chicken meals to trade, so each chicken meal becomes more valuable to us. This pattern is a common one in economics, known as diminishing returns. The law of diminishing marginal returns tells us that each additional unit of a good consumed provides less additional satisfaction than the previous unit. The term marginal, which refers to an extra unit, is used by economists to refer to the change resulting from one additional unit of an action.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.