Table of Contents |

A leaders, we must first look to ourselves, and our expectations of ourselves and others, to begin to understand how what we perceive and think impacts our actions and behaviors. Let’s consider why we don’t all see things the same way.

The statement, "the limits of our language are the limits of our world," attributed to Ludwig Wittgenstein, speaks to the connection between our language use, expectations and our experiences. Our language shapes how we understand the world, acting as a framework that helps us categorize and articulate what we perceive. If we lack the words or grammatical structures to express an idea, like a cultural difference in behavior, it becomes difficult to fully grasp or acknowledge it. Like sunglasses, it can color our perceptions and experiences.

Consider the diverse ways different languages categorize colors, emotions, or time. Some languages have a single word for concepts that require multiple words in others, or vice-versa. These linguistic differences are not arbitrary; they reflect and reinforce distinct ways of perceiving and interacting with the world. For instance, if a language lacks a specific term for a nuanced emotional state (like ennui), speakers of that language might be less likely to consciously identify or differentiate that emotion, even if they experience its physiological manifestations in the real world. Their "world" of emotional understanding is, in a sense, limited by their linguistic repertoire.

IN CONTEXT

Even within a culture, there may be different “languages” in the way people use words and engage in conversation. In many cultures, including the mainstream U.S., men are more likely to talk about facts and things while women talk about relationships and feelings. “In a minute,” tends to mean exactly that in the Northeastern United States and may mean “in an hour or two,” in the Western U.S. Nonverbal communication varies a lot within the country, with some subcultures valuing proximity and touch while other subcultures want physical distance between parties.

Differences in vocabulary and communication style can lead to misunderstandings, and may even reflect different ways of thinking. The syntax and grammar of a language can influence how we perceive causality, agency, or relationships between objects and events. A language that emphasizes the passive voice might subtly shift the speaker's focus away from the actor and towards the action itself, thereby shaping their understanding of responsibility. In essence, our language provides the conceptual scaffolding upon which our entire worldview is built.

To expand our language, whether through learning new vocabulary, mastering a new tongue, or even engaging with complex philosophical ideas, is to expand the boundaries of our perceived world, opening up new possibilities for thought, understanding, and interaction. Limitations in language can inadvertently impose limits on our very capacity to comprehend and engage with the richness of existence.

IN CONTEXT

Not long ago, gender was often clearly associated with specific professions, and even our language reflected that bias. A policeman was expected to be a man, as the word indicates but as times changed, the term we use became police officer. An “officer” is gender-neutral, and carries no explicit bias, preference, or expectation associated with gender. While we might observe there are still many opportunities for continued progress, we can also observe here how language sets up expectations.

On the flip side, terms like “male nurse,” indicated gender because those roles were usually occupied by women. But “male” is irrelevant to the duties of the job, and we use the gender-neutral term “nurse” for everyone.

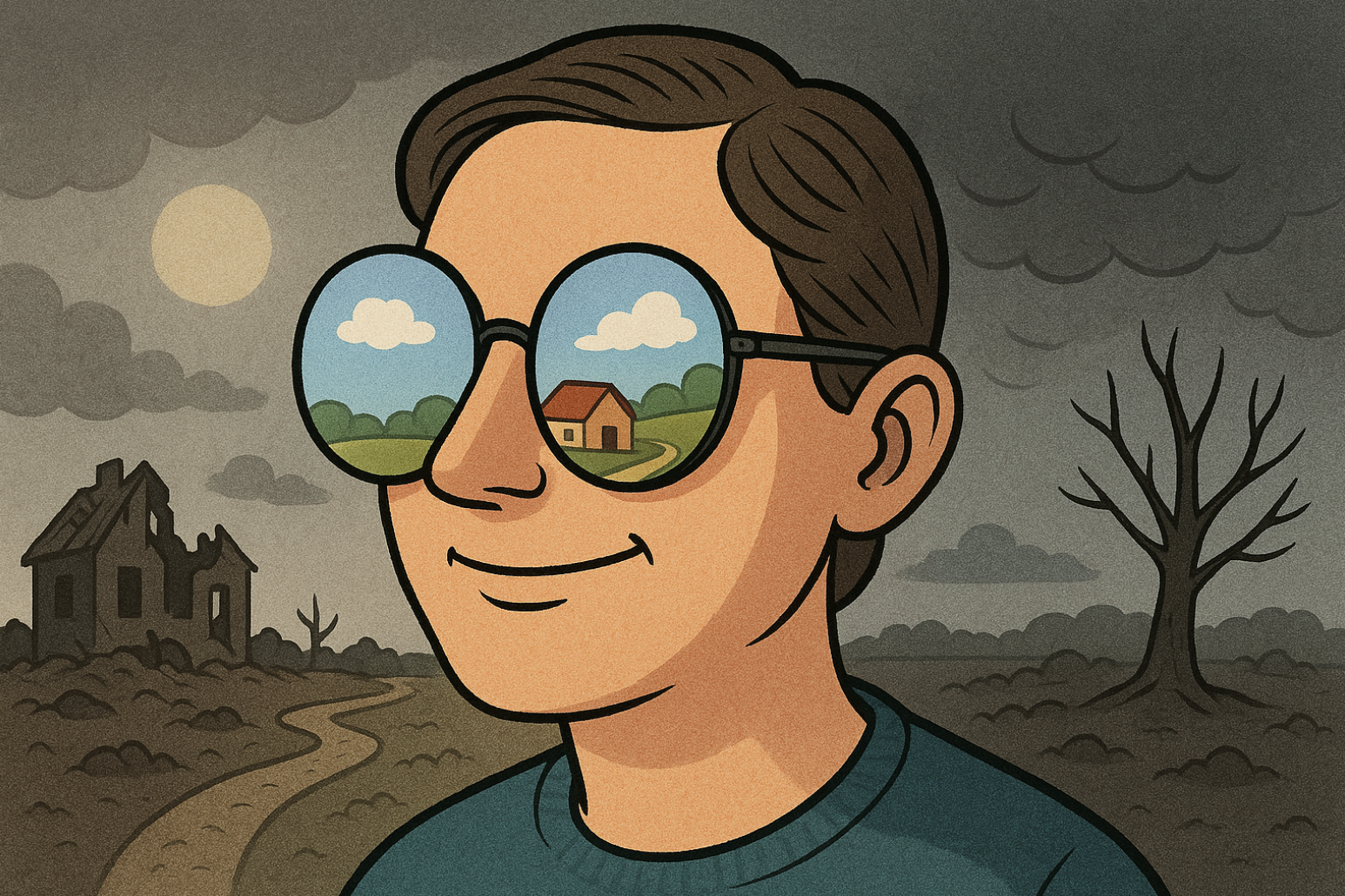

Do we all see through cultural “sunglasses?”

Our perception of the world is not a neutral act. It is profoundly filtered through a cultural "lens," much like wearing sunglasses that subtly tint everything we see. This lens is a complex amalgamation of shared values, beliefs, norms, and historical experiences that shape how we make sense of our surroundings. It is an inherited framework, often operating below our conscious awareness, yet it dictates what we notice, what we prioritize, and how we categorize information.

Integral to this cultural lens is what Jürgen Habermas refers to as preunderstanding. This concept highlights that we do not approach new situations as blank slates. Instead, we carry with us a reservoir of prior knowledge, assumptions, and expectations derived from our upbringing, education, and social interactions within our specific cultural context. This preunderstanding acts as a cognitive filter, preparing us to perceive certain phenomena in particular ways. For instance, a gesture that signifies agreement in one culture might be interpreted as an insult in another, not because the gesture itself changes, but because our preunderstanding assigns different meanings to it.

This cultural lens and preunderstanding directly influence what we actually perceive. We selectively attend to stimuli that resonate with our existing mental models, often overlooking or misinterpreting those that do not fit. This selective perception then cascades into our interpretation of events. When observing actions and behaviors, we unconsciously draw upon our cultural scripts to assign meaning. A quick decision by a leader might be interpreted as decisive in a culture that values swift action, but as autocratic in a culture that prioritizes consensus. The same behavior elicits different interpretations because the underlying cultural assumptions about appropriate leadership vary.

Our responses and actions are not merely reactions to an objective reality, but rather to our culturally mediated interpretation of that reality. If a perceived action is interpreted as a threat, our response will be one of defense; if interpreted as an invitation, our response will be one of engagement. These responses, in turn, reinforce our cultural lens, making it even more entrenched. The continuous interplay between our cultural lens, preunderstanding, perception, interpretation, and subsequent actions creates a self-perpetuating cycle, demonstrating the deeply embedded and subjective nature of human experience within its cultural context.

Cultural expectations significantly shape the perception of leadership across diverse societies. The work of Edward T. Hall and Geert Hofstede offers compelling frameworks for understanding these profound influences, highlighting how ingrained cultural values dictate what is considered effective, appropriate, and even desirable in a leader.

Edward T. Hall's dimensions of culture offer insight into these differing expectations. One dimension is that of high-context and low-context cultures.

In high-context cultures, such as those found in Japan or China, communication relies heavily on implicit cues, non-verbal signals, and shared understanding within a group. Leaders in these cultures might be perceived as effective if they communicate subtly, understand unstated norms, and maintain harmonious relationships. Their authority may be more implicitly understood rather than explicitly stated.

In low-context cultures, like Germany or the United States, communication is direct, explicit, and relies on precise verbal messages. A leader in a low-context environment would likely be perceived as effective by being clear, direct, and explicit in their instructions and expectations. Misunderstandings can arise when a high-context leader's subtle cues are missed by low-context followers, or when a low-context leader's directness is seen as rude or aggressive in a high-context setting.

Hall's time-orientations further illuminate our diverse perceptions of leadership. Monochronic cultures view time as linear and segmented, emphasizing punctuality and completing one task at a time. Leaders in such cultures are expected to be organized, adhere to schedules, and prioritize efficiency. Polychronic cultures, on the other hand, perceive time as more fluid, allowing for multiple tasks simultaneously and prioritizing relationships over strict schedules. A leader in a polychronic culture might be perceived positively for their flexibility, ability to manage multiple interactions, and willingness to adjust plans for the sake of relationships. A monochronic leader's strict adherence to schedules might be seen as inflexible or even uncaring in a polychronic context.

Geert Hofstede's cultural dimensions provide another powerful lens for examining leadership perceptions. His Power Distance Index (PDI) is particularly relevant. In high-power distance cultures, like Malaysia or Mexico, there is a clear acceptance of hierarchical structures and unequal distribution of power. Leaders in these societies are expected to be authoritative, decisive, and may not engage in extensive consultation with subordinates. Their authority is often respected without question. Employees in these cultures may expect leaders to take charge and provide clear direction. In contrast, low-power distance cultures, such as Denmark or Israel, value equality and strive for a more consultative and participative leadership style. Leaders here are expected to be accessible, involve subordinates in decision-making, and minimize status differences. A directive leadership style that works well in a high-power distance culture could be seen as autocratic or disrespectful in a low-power distance environment.

Hofstede's Individualism versus Collectivism dimension also influences how leaders are perceived. In individualistic societies, like the United States, leaders are often admired for their personal achievements, independence, and ability to celebrate individual success. Leadership is often about empowering individuals. In collectivistic cultures, such as China or South Korea, leaders are expected to prioritize group harmony, loyalty, and the well-being of the group. Effective leaders in these contexts build strong relationships, promote teamwork, and ensure that group goals are met. A leader focused solely on individual performance might be seen as divisive in a collectivistic setting.

The cultural lenses provided by Edward T. Hall and Geert Hofstede underscore that there is no universal model for effective leadership. Cultural expectations, shaped by communication styles, time perceptions, power dynamics, and societal emphasis on individualism or collectivism, profoundly dictate what qualities and behaviors are valued and perceived as legitimate in a leader. Understanding these nuances is paramount for leaders operating in our interconnected world, enabling them to adapt their approach and build effective relationships across cultural boundaries.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's assertion that "the limits of our language are the limits of our world" perfectly aligns with how our cultural "lens" shapes perception. This linguistic framework inherently defines what we can conceive and articulate. What we think influences how we communicate and interact. Jürgen Habermas's "preunderstanding" represents this ingrained, often unconscious, cognitive filter, which is fundamentally built upon the language and shared meanings of our culture. Insights from Edward T. Hall and Geert Hofstede demonstrate how distinct cultural dimensions—like communication styles or power distance—are embedded within our linguistic structures and influence our preunderstanding. Our culturally informed language dictates what we perceive, interpret, and ultimately, what our "world" encompasses.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.