Table of Contents |

Humoral immunity refers to mechanisms of adaptive immunity that are mediated by antibodies secreted by B lymphocytes, or B cells, which produce antibodies.

Antibodies were the first component of the adaptive immune response characterized by scientists working on the immune system. It was already known that individuals who survived a bacterial infection were immune to reinfection with the same pathogen. Early microbiologists took serum from an immune patient and mixed it with a fresh culture of the same type of bacteria, then observed the bacteria under a microscope. The bacteria became clumped in a process called agglutination. When a different bacterial species was used, the agglutination did not happen. Thus, there was something in the serum of immune individuals that could specifically bind to and agglutinate bacteria. Scientists now know the cause of the agglutination is an antibody molecule, also called an immunoglobulin.

Not surprisingly, the same genes encode both the secreted antibodies and the surface immunoglobulins. One minor difference in the way these proteins are synthesized distinguishes a naïve B cell with antibodies on its surface from an antibody-secreting plasma cell with no antibodies on its surface. The antibodies of the plasma cell have the exact same antigen-binding site and specificity as their B cell precursors.

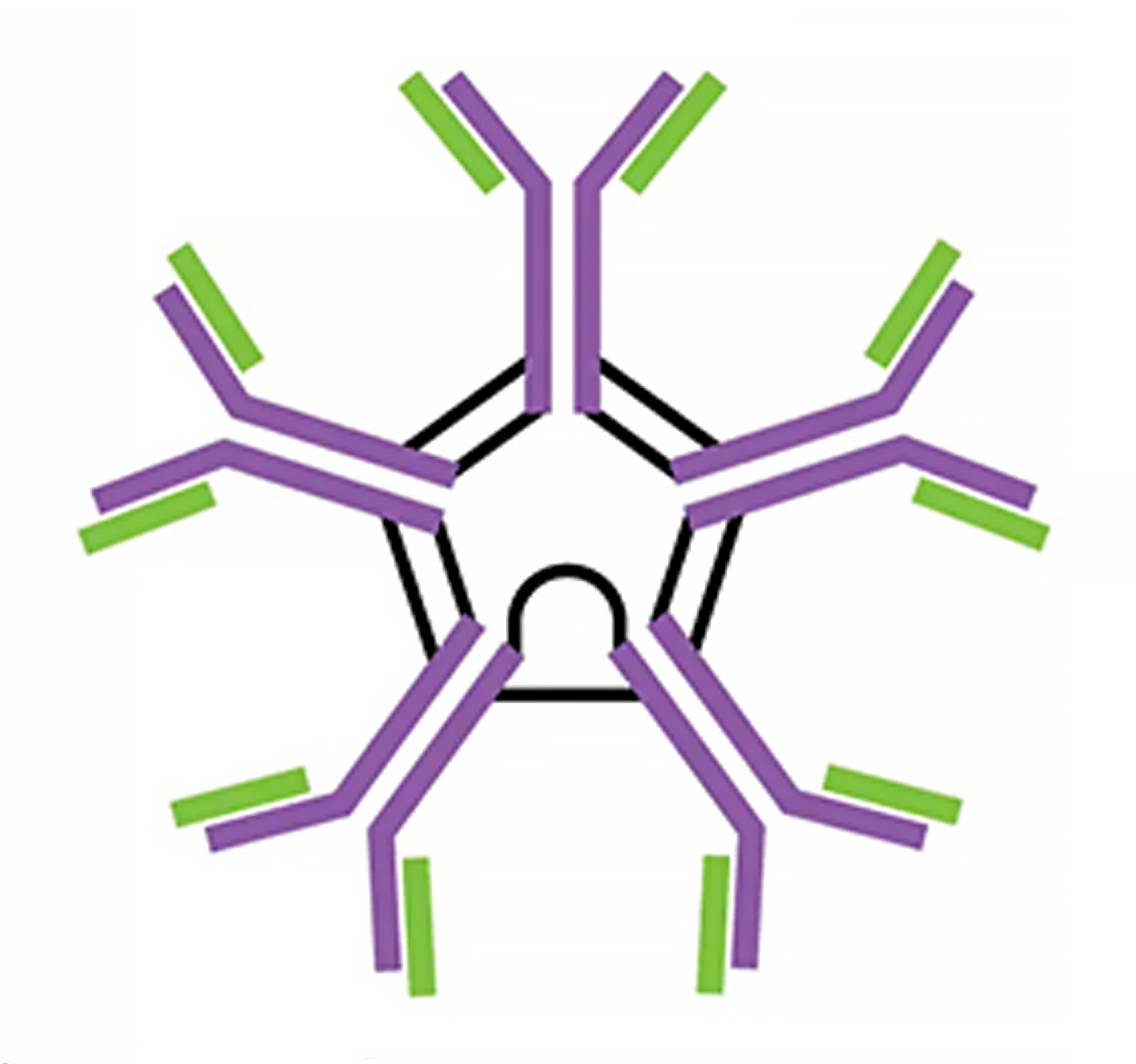

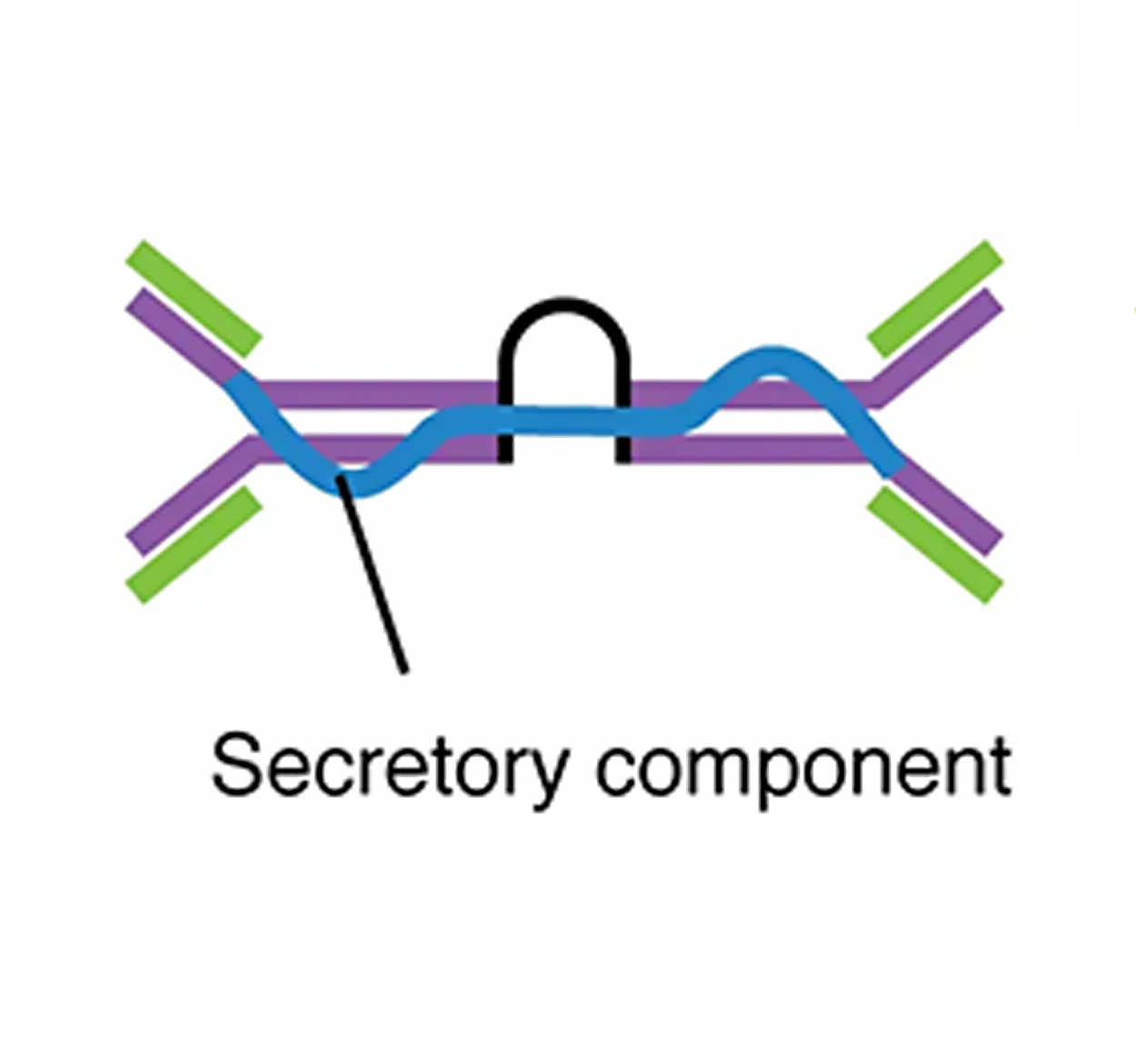

There are five different classes of antibodies found in humans: IgM, IgD, IgG, IgA, and IgE. Each of these has specific functions in the immune response, so by learning about them, researchers can learn about the great variety of antibody functions critical to many adaptive immune responses.

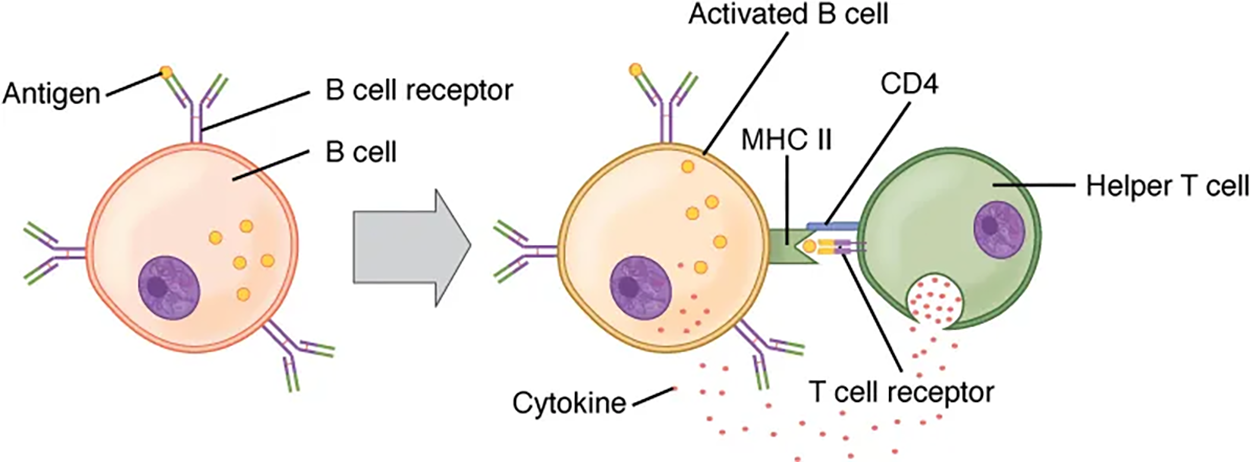

B cells do not recognize antigen in the complex fashion of T cells. However, B cells can recognize native, unprocessed antigen and do not require the participation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and antigen-presenting cells.

As previously discussed, Th2 cells secrete cytokines that drive the production of antibodies in a B cell, responding to complex antigens such as those made by proteins. On the other hand, some antigens are T cell independent. A T cell-independent antigen is usually in the form of repeated carbohydrate parts found on the cell walls of bacteria. Each antibody on the B cell surface has two binding sites, and the repeated nature of T cell-independent antigen leads to crosslinking of the surface antibodies on the B cell. The crosslinking is enough to activate the B cell in the absence of T cell cytokines.

A T cell-dependent antigen, on the other hand, usually is not repeated to the same degree on the pathogen and thus does not crosslink surface antibodies with the same efficiency. To elicit a response to such antigens, the B and T cells must come close together. The B cell must receive two signals to become activated. Its surface immunoglobulin must recognize native antigens. Some of this antigen is internalized, processed, and presented to the Th2 cells on an MHC class II molecule, which you will learn more about in a future lesson. When this process is complete, the B cell has undergone sensitization, which refers to its first exposure to an antigen. The T cell then binds using its antigen receptor and is activated to secrete cytokines that diffuse to the B cell, finally activating it completely. Thus, the B cell receives signals from both its surface antibody and the T cell via its cytokines and acts as a professional antigen-presenting cell in the process.

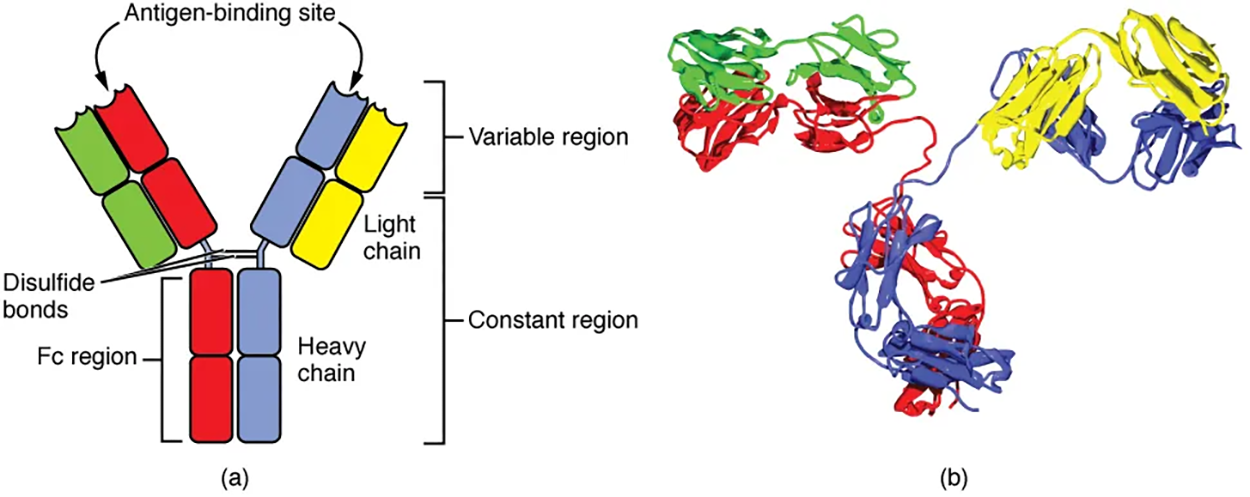

Antibodies are glycoproteins consisting of two types of polypeptide chains with attached carbohydrates. The heavy chain and the light chain are the two polypeptides that form the antibody. The main differences between the classes of antibodies are in the differences between their heavy chains, but as you shall see, the light chains have an important role, forming part of the antigen-binding site on the antibody molecules.

All antibody molecules have two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains. (Some antibodies contain multiple units of this four-chain structure.) The Fc region of the antibody is formed by the two heavy chains coming together, usually linked by disulfide bonds. The Fc portion of the antibody is important in that many effector cells of the immune system have Fc receptors. Cells having these receptors can then bind to antibody-coated pathogens, greatly increasing the specificity of the effector cells. At the other end of the molecule are two identical antigen-binding sites.

In general, antibodies have two basic functions. They can act as the B cell antigen receptor, or they can be secreted, circulate, and bind to a pathogen, often labeling it for identification by other forms of the immune response.

Of the five antibody classes (described in the table below), only two can function as the antigen receptor for naïve B cells: IgM and IgD. Mature B cells that leave the bone marrow express both IgM and IgD, but both antibodies have the same antigen specificity. Only IgM is secreted, however, and no other non-receptor function for IgD has been discovered.

| The Five Immunoglobulin (Ig) Classes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM pentamer | IgG monomer | Secretory IgA dimer | IgE monomer | IgD monomer | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Heavy chains | μ | γ | α | ε | δ |

| Number of antigen-binding sites | 10 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Molecular weight (Daltons) | 900,000 | 150,000 | 385,000 | 200,000 | 180,000 |

| Percentage of total antibody in serum | 6% | 80% | 13% | 0.002% | 1% |

| Crosses placenta | no | yes | no | no | no |

| Fixes complement | yes | yes | no | no | no |

| Fc binds to | Phagocytes | Mast cells and basophils | |||

| Function | Main antibody of primary responses, best at fixing complement; the monomer form of IgM serves as the B cell receptor | Main blood antibody of secondary responses, neutralizes toxins, opsonization | Secreted into mucus, tears, saliva, colostrum | Antibody of allergy and antiparasitic activity | B cell receptor |

Antibodies have extremely significant functions against extracellular pathogens and toxins. Antibodies circulate freely and can even be transferred from one individual to another to temporarily protect against infectious disease.

EXAMPLE

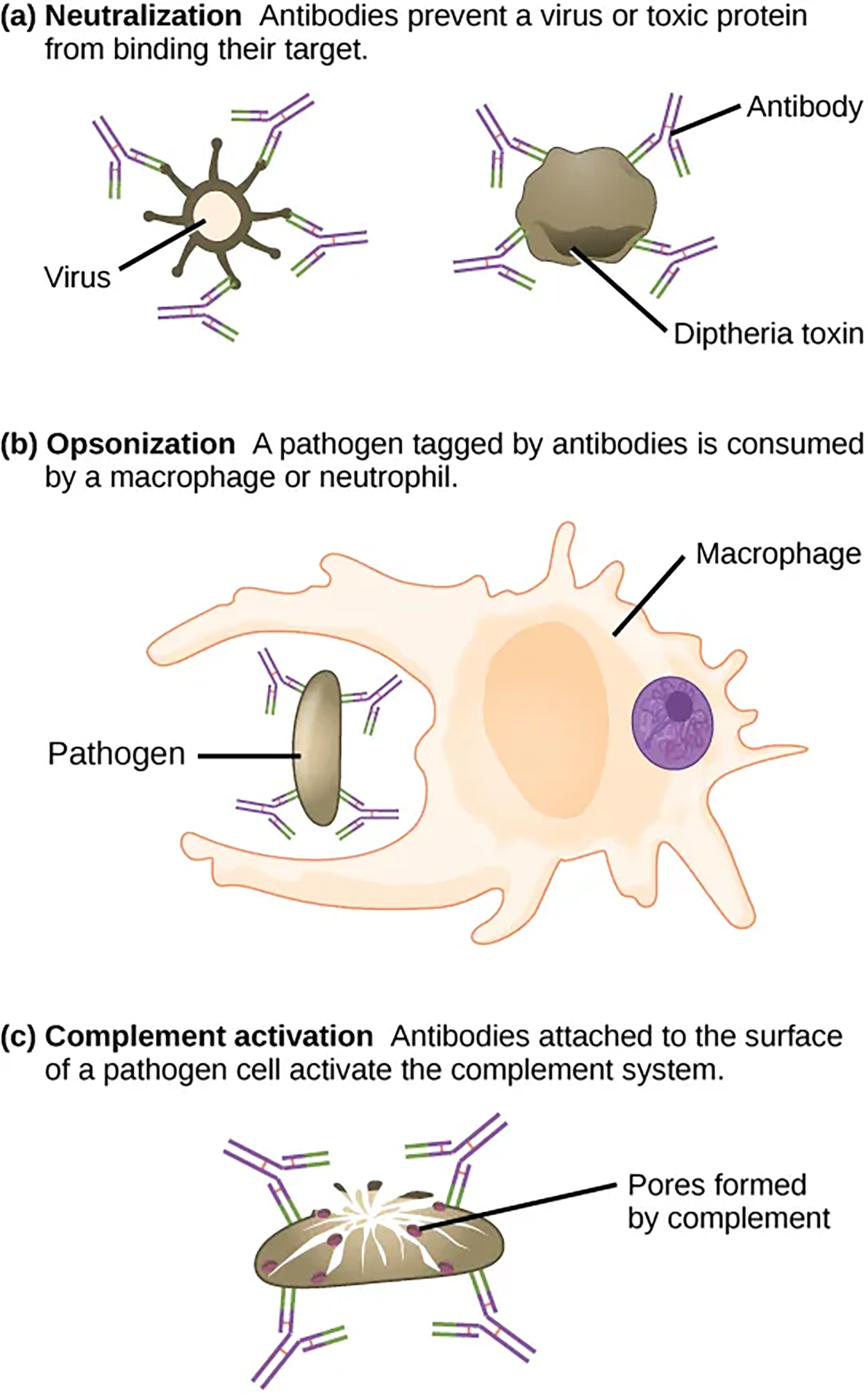

A person who has recently produced a successful immune response against a particular disease agent can donate blood to a nonimmune recipient and confer temporary immunity through antibodies in the donor’s blood serum by passive immunity.Neutralizing antibodies are the basis for the disease protection offered by vaccines. Vaccinations for diseases that commonly enter the body via mucous membranes, such as influenza, are usually formulated to enhance IgA production. Antibodies coat extracellular pathogens and neutralize them, as illustrated below. Antibody neutralization, which occurs in the blood, lymph, and other body fluids and secretions, protects the body constantly because it can prevent pathogens from entering and infecting host cells. The neutralized antibody-coated pathogens can then be filtered by the spleen and eliminated in urine or feces.

As previously discussed, antibodies can also function by marking pathogens for destruction by phagocytic cells, such as macrophages or neutrophils, in a process called opsonization. In a process called complement activation, some antibodies attach to the surface of a pathogen cell, which activates the complement cascade. The combination of antibodies and complement promotes the rapid clearing of pathogens.

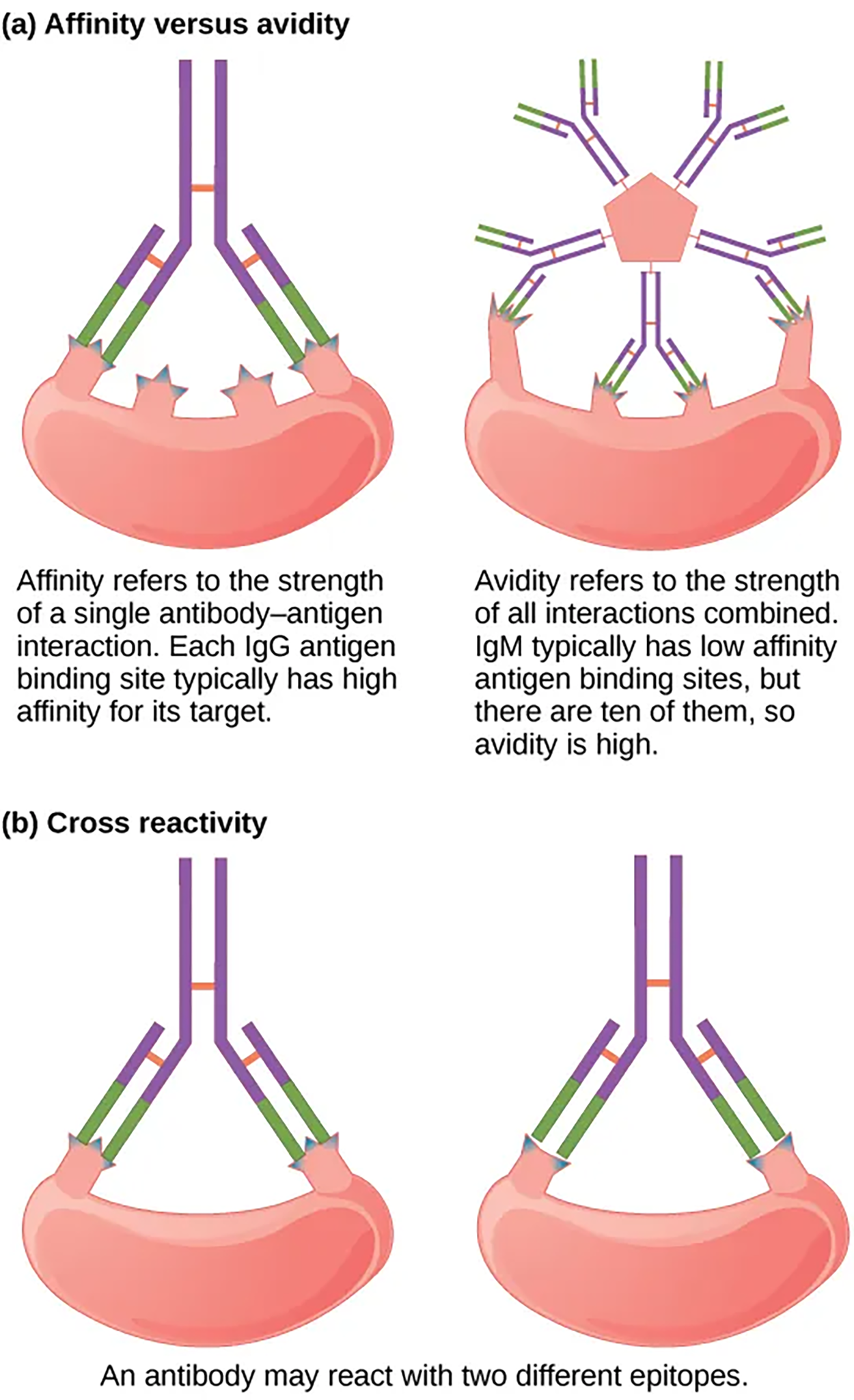

The term avidity describes binding by antibody classes that are secreted as joined, multivalent structures (such as IgM and IgA). Although avidity measures the strength of binding, just as affinity does, avidity is not simply the sum of the affinities of the antibodies. The avidity depends on the number of identical binding sites on the antigen being detected, as well as other physical and chemical factors.

Antibodies secreted after binding to one epitope (the part to which an antibody binds) on an antigen may exhibit cross-reactivity for the same or similar epitopes on different antigens. Because an epitope corresponds to such a small region (the surface area of about four to six amino acids), it is possible for different macromolecules to exhibit the same molecular identities and orientations over short regions. Cross-reactivity describes when an antibody binds not to the antigen that elicited its synthesis and secretion, but to a different antigen.

Cross-reactivity can be beneficial if an individual develops immunity to several related pathogens despite having only been exposed to or vaccinated against one of them.

EXAMPLE

Antibody cross-reactivity may occur against the similar surface structures of various Gram-negative bacteria. Conversely, antibodies raised against pathogenic molecular components that resemble self-molecules may incorrectly mark host cells for destruction and cause autoimmune damage.

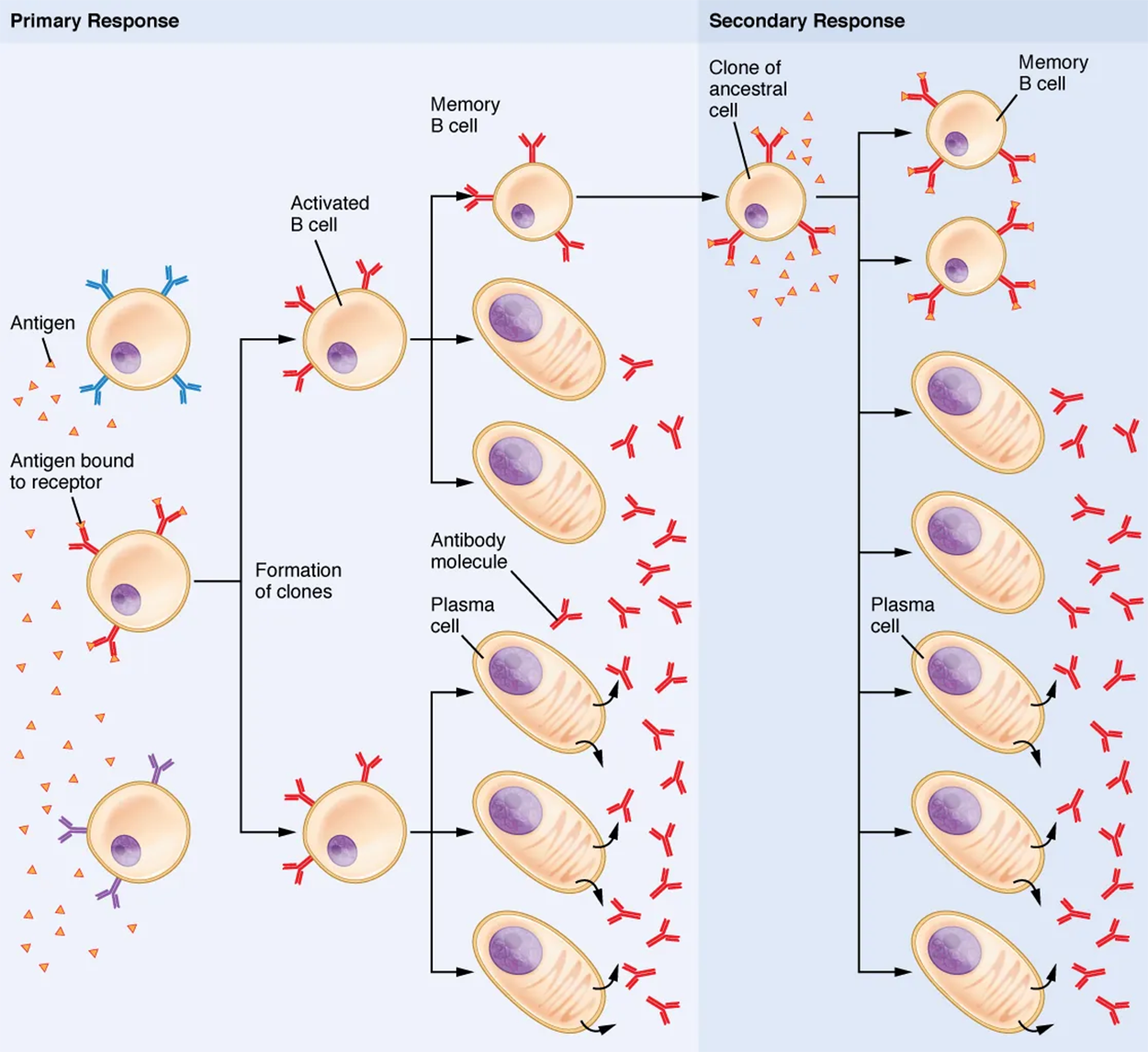

Clonal selection and expansion work much the same way in B cells as in T cells. Only B cells with appropriate antigen specificity are selected for and expanded. Eventually, the plasma cells secrete antibodies with antigenic specificity identical to those that were on the surfaces of the selected B cells.

Notice in the figure below that both plasma cells and memory B cells are generated simultaneously during primary response. During a primary B cell immune response, both antibody-secreting plasma cells and memory B cells are produced. These memory cells lead to the differentiation of more plasma cells and memory B cells during secondary responses.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) OPENSTAX “BIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/BIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION (2) OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION (3) OPENSTAX “CONCEPTS OF BIOLOGY”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/CONCEPTS-BIOLOGY/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSING (1, 2, & 3): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.