Table of Contents |

Cave paintings are among the earliest forms of visual communication, dating back to the Upper Paleolithic Age (circa 30,000 BC/BCE). These ancient illustrations, found in locations such as the Lascaux and Chauvet caves in France, provide invaluable insights into the lives and minds of our ancestors. The paintings often depict animals, human figures, and abstract symbols, serving as visual aids for mythological stories, oral histories, and religious or ceremonial purposes. While these paintings date back to the dawn of the human era in primeval Europe, they were present in cultures around the world dating to the 19th century in the Americas. The image below shows rock paintings in Tassili N’Ajjer, Algeria. These North African paintings depict people following and riding camels. Illustrations like these served as a means of communication and physical recordkeeping for people and societies with no written language.

Visual communication in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt laid the foundation for many modern design principles. Mesopotamian art, dating back over 7,000 years, utilized pictograms and cuneiform writing to convey complex ideas and record transactions. Pictograms are graphical symbols that convey meaning through their visual resemblance to physical objects. Cuneiform is one of the earliest writing systems, originating with the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia around 3,500 BCE. The name “cuneiform” comes from the Latin word for “wedge-shaped,” reflecting the script’s distinctive marks made by pressing a reed stylus into clay tablets.

In Egypt, hieroglyphics combined logographic and alphabetic elements, creating a sophisticated system of writing that adorned temples, tombs, and monuments. This system of pictorial symbols was used to represent sounds, objects, and ideas. Hieroglyphics were primarily employed for religious texts, administrative records, and monumental inscriptions, allowing Egyptians to document historical events and convey religious rituals through visual storytelling. The image below shows hieroglyphics from the Temple of Edfu, dedicated to the Egyptian god Horace on the West Bank of the Nile in Upper Egypt.

From the pre-Roman Era through the Dark Ages and the Renaissance, Europe saw the rise of great civilizations and cultures. These societies shared many commonalities but were also diverse. While countries like Italy became home to some of the most remarkable artists in history, the lands of Northern Europe gave rise to one of the earliest forms of a written alphabet.

The Vikings used runes, a system of writing, for various purposes including memorial inscriptions, magic, and communication. Runes are letters from ancient alphabets used by Germanic peoples before the adoption of the Latin alphabet. The runic alphabet, known as the Futhark, consists of characters carved into wood, stone, and metal. These runes were not only functional but also held symbolic meanings, often associated with Norse mythology and cosmology.

The Futhark is the oldest form of the runic alphabets used by Germanic tribes. Named after its first six letters (F, U, Þ, A, R, K), the Elder Futhark was in use from around the 2nd to 8th centuries. These runes were carved into wood, stone, and metal, serving as a means of communication, recording historical events, and marking graves.

As the Germanic tribes migrated and settled in different regions, the runic alphabet evolved. When the Anglo-Saxons arrived in Britain, they adapted the Elder Futhark to create the Anglo-Saxon runes, also known as the Futhorc. This new alphabet included additional characters to accommodate the sounds of Old English. The Anglo-Saxon runes were used from the 5th to 11th centuries, primarily for inscriptions on monuments, coins, and everyday objects, reflecting the cultural and linguistic shifts of the time. The image below shows the runic forms of Elder Futhark.

Medieval art, spanning roughly from the 5th to the late 15th century, was deeply intertwined with the Christian Church. Illuminated manuscripts, stained glass windows, and frescoes were common forms of visual communication. A fresco is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid, or wet, lime plaster. These artworks were used to convey religious stories and moral lessons to a largely illiterate population. The use of symbolism and iconography was prevalent, with specific colors, animals, and objects representing various theological concepts.

Blue became a prominent color in art during the Renaissance Period, thanks to advancements in technology that enabled the mass production of blue pigments like Prussian blue and ultramarine. Prior to this, blue was a rare and costly color, often sourced from lapis lazuli, which began use as a pigment in the 6th century. The Middle Ages also saw an increase in blue in religious murals and tapestries. This is directly linked to visual interpretations of the Virgin Mary adorned in blue garments. So many artists painted the Virgin Mother in blue due to the color’s popularity that her visual representations retain blue and white clothing to this day.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Madonna Litta, created in the 1490s, depicts a blue-robed Virgin Mary nursing the Christ child. This famous example of religious art shows the popularity of blue in religious iconography.

Symbology became an important means of visual communication in Europe, largely due to the illiteracy of the mass population. People learned to share information and ideas through images. Visual representations of thoughts, and even chemical formulas, developed into a heightened communication form for some who created complex coded systems based on illustrations.

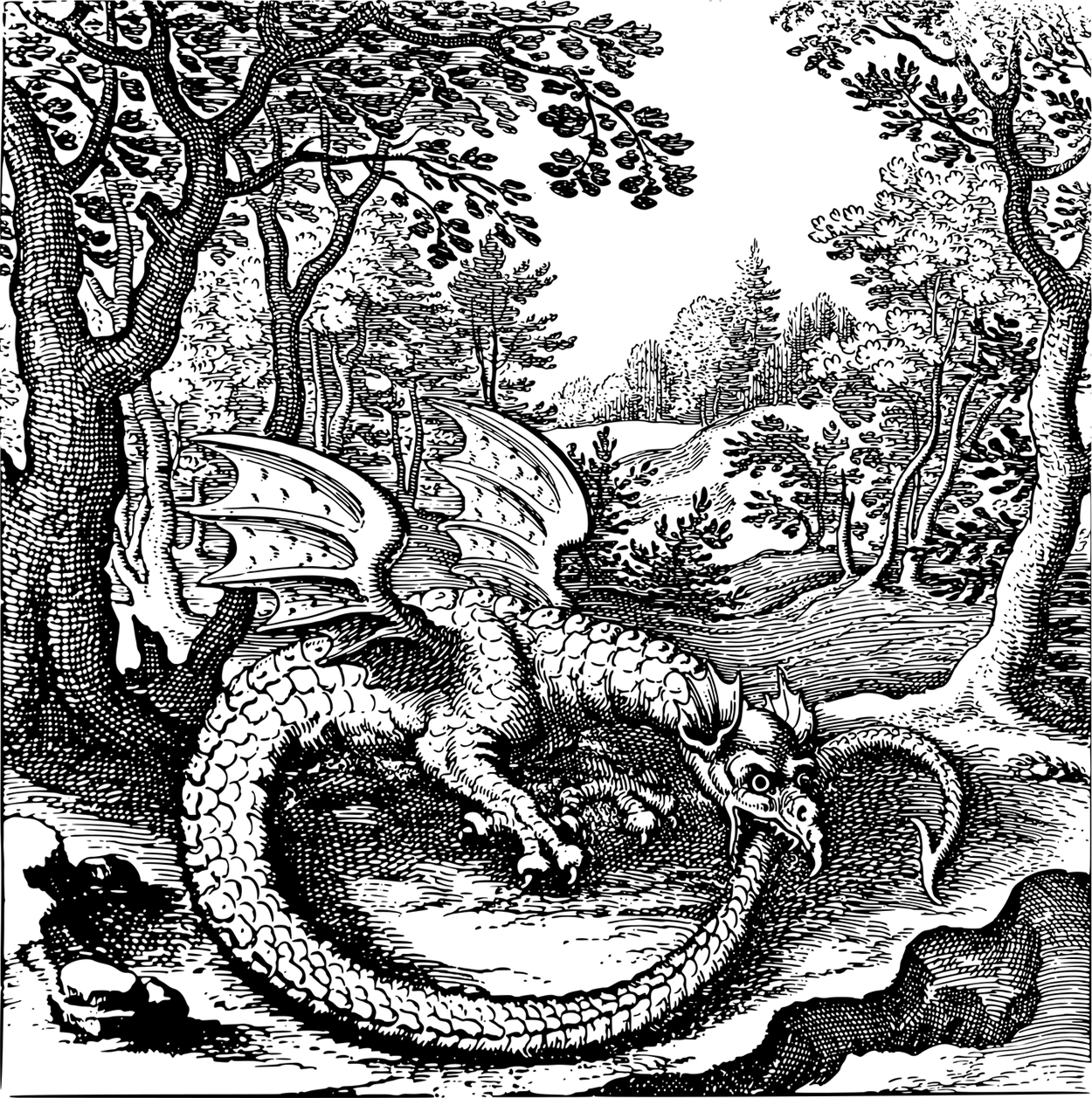

Alchemy, a precursor to modern chemistry, was rich in symbolic imagery. Although alchemy originated in China and was practiced in Greco-Roman Egypt and across the Byzantine Empire, it adopted a unique form of visual communication in Europe between the Middle Ages and the 18th century. Alchemists used a variety of visual symbols to represent elements, processes, and metaphysical concepts. These symbols were often depicted in manuscripts and engravings, serving as a coded language for those initiated into the alchemical arts. These illustrations served as visual codes to record formulas for potions, elixirs, and chemical processes purported to change the properties of various metals and elements.

Below is an example of the type of symbolism used by alchemists to record their secret formulas and processes. This black and white image of a dragon biting its own tail is called an ouroboros. A variant design for an ouroboros is a snake swallowing its own tail. An ouroboros represents eternity because the form of the serpent devouring itself forms a circle with no end and no beginning. This symbol has its origins in Egyptian and Ancient Greek traditions but was adopted by alchemists. Other popular symbols included a lion, the sun, and swans. Colors also had coded meanings in alchemical symbolism.

Tarot cards, which originated in the 15th century, are another example of visual communication rich in symbolism. In fact, much of the symbolism found in the art of the tarot deck is derived from the same symbols used by European alchemists. Each card in the tarot deck is adorned with intricate imagery that conveys specific meanings and archetypes. The Major Arcana, for example, is a set of 22 tarot cards that represent the spiritual journey of the soul. This deck includes cards like The Fool, The Magician, and The High Priestess, each representing different aspects of the human experience and spiritual journey.

Wood engraving, a printmaking technique that emerged in the late 18th century, allowed for the mass production of images and texts. This technique involved carving an image into the surface of a wooden block, which was then inked and pressed onto paper. These types of engravings were used to illustrate books, newspapers, and even posters. Wood engraving made visual communication more accessible to the general populace at the time.

Japanese woodblock art, particularly the ukiyo-e genre, flourished during the Edo Period (1603–1868). Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige created iconic works that are celebrated for their intricate details, vibrant colors, and dynamic compositions. Woodblock printing involved an elaborate process which included drawing, carving designs into blocks of wood, and applying ink to the engravings.

The illustration below is a famous design created by Japanese woodblock artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1753–1806). The engraving depicts the legendary warrior Rori Hakucho Chojun crashing through a water gate, bearing his sword in his teeth while arrows rain down around him.

Symbolism is deeply rooted in the cultural and spiritual practices of Indigenous American tribes. For example, Navajo symbols represent the cultural and spiritual beliefs of the Navajo people, each carrying significant meanings and stories. For instance, the Thunderbird symbolizes happiness and serenity, while Kokopelli, often depicted as a humpbacked flute player, represents childbirth and agriculture. The Bear stands for strength and resilience, reflecting the Navajo’s respect for this powerful animal. Deer Tracks symbolize an abundance of food, highlighting the importance of deer as a source of sustainment. The Sun is a symbol of good cheer and fortune, essential for life and growth. These symbols are not just artistic expressions but are integral to Navajo identity, often found in sand paintings, jewelry, and other artworks. The image below shows a variety of symbols adorning Navajo pottery.

The horse societies of the American Plains carried medicine shields, sacred objects reflecting a warrior’s personal vision and spiritual guidance. These shields were made from buffalo hide and widely used by Plains tribes such as the Apache and Comanche. Medicine shields were created by young men as part of a coming-of-age ritual, usually after going on a spiritual journey, or vision quest. These shields were adorned with intricate symbols, sometimes including patterns of the stars that could be used as a map if the shield’s owner lost his way. Medicine shields were also thought to possess magical powers of protection. Similarly, horses were adorned with symbolic decorations, such as painted symbols indicating enemies slain in battle, or the number of stolen ponies captured during raids. The horse a warrior rode into battle was known as his war horse, or medicine horse. The use of vibrant colors and meaningful symbols in both medicine shields and war horses highlights the profound connection between art, spirituality, and daily life in Indigenous cultures.

Indigenous symbolism has been romanticized by artists like Charles Marion Russell (1864–1926). Russell created over 2,000 illustrations of Indigenous tribesmen, cowboys, and other scenes from the American West. The image below is Russell’s vision of the Battle of Little Bighorn from the perspective of the Lakota and the Cheyenne. Note the symbols of the hand and the sun painted on the horse’s flank. Hands were often painted on medicine horses to indicate that the horse had knocked over or trampled an enemy.

The history of visual communication is a testament to humanity’s enduring desire to express, record, and share ideas through images. From the earliest cave paintings to the sophisticated designs of alchemists and Indigenous American symbols, visual communication has evolved across cultures and eras, reflecting the diverse ways in which humans perceive and interact with the world. This highlights the significance of visual symbols in shaping our understanding of history, culture, and identity.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.