Table of Contents |

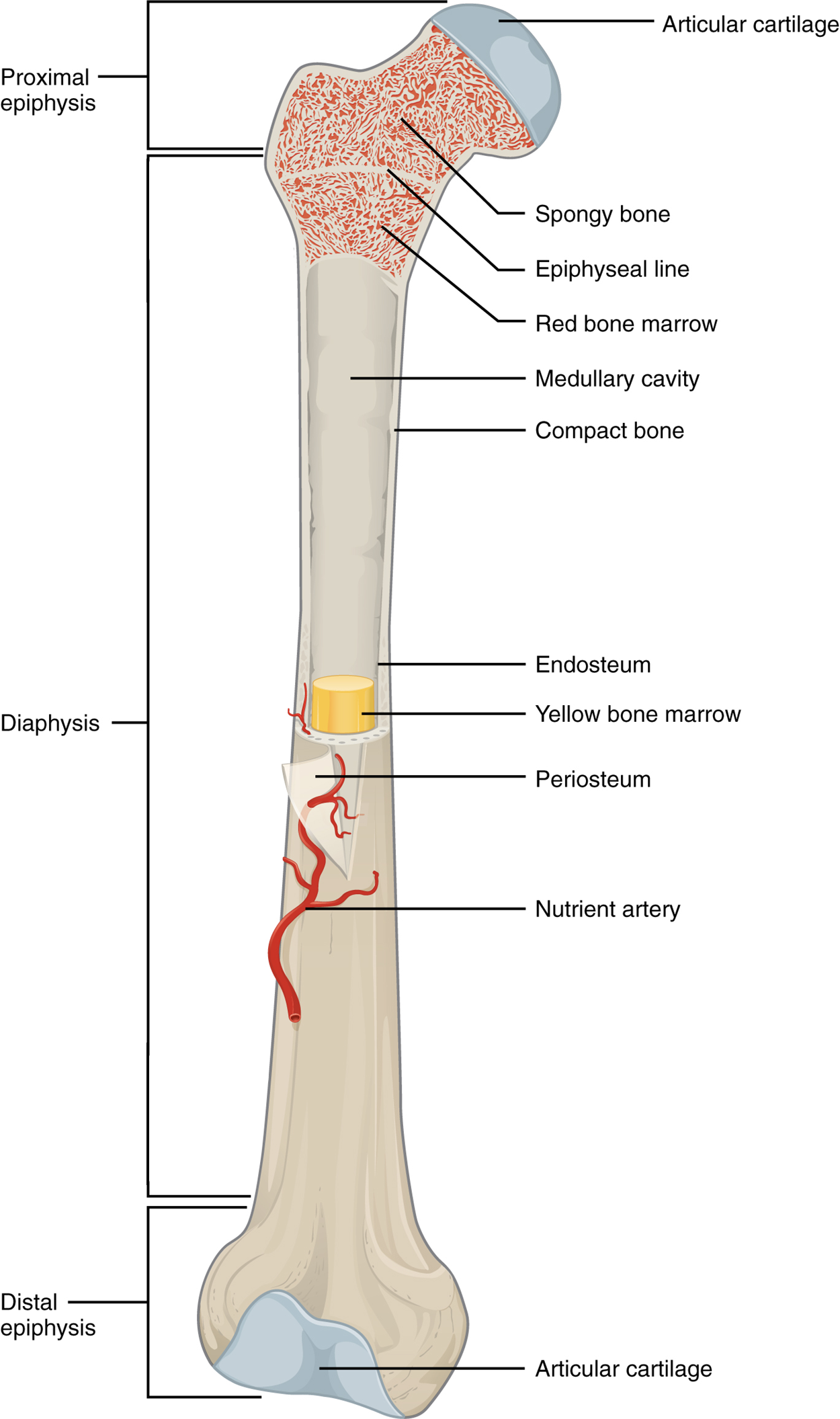

The structure of a long bone (as opposed to the other four categories based on shape) allows for the best visualization of all of the parts of a bone. As a whole, a long bone can be divided into two parts: the diaphysis and the epiphysis. The diaphysis is the tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of the bone. The hollow central region in the diaphysis is called the medullary cavity, which is filled with yellow marrow. The walls of the diaphysis are predominantly composed of compact bone, a dense osseous tissue able to sustain compressive forces.

The wider section at each end of the bone is called the epiphysis (plural, epiphyses), which is predominantly filled with spongy bone, a porous osseous tissue which provides strength along with storage of red bone marrow. In a growing bone, where each epiphysis meets the diaphysis, there is an epiphyseal plate (growth plate), a layer of hyaline cartilage in a growing bone. When the bone stops growing in early adulthood (approximately 18–21 years), the cartilage is replaced by osseous tissue and the epiphyseal plate becomes an epiphyseal line.

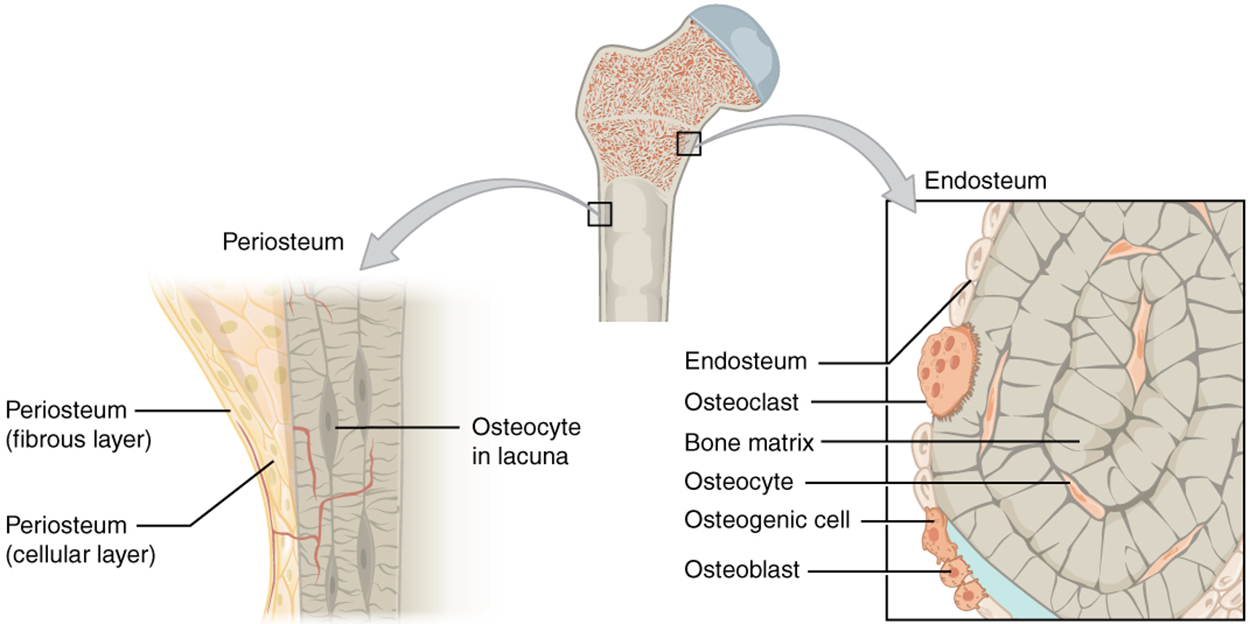

The medullary cavity has a thin connective tissue lining called the endosteum (endo, inside; osteo, bone), where bone growth, repair, and remodeling occur. The outer surface of the bone is covered with a fibrous membrane called the periosteum (peri, around or surrounding). The periosteum contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels that nourish compact bone. Tendons and ligaments also are connected to bones by attaching to the periosteum. The periosteum covers the entire outer surface except where the epiphyses meet other bones to form joints. In this region, the epiphyses are covered with articular cartilage, a thin layer of cartilage that reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber.

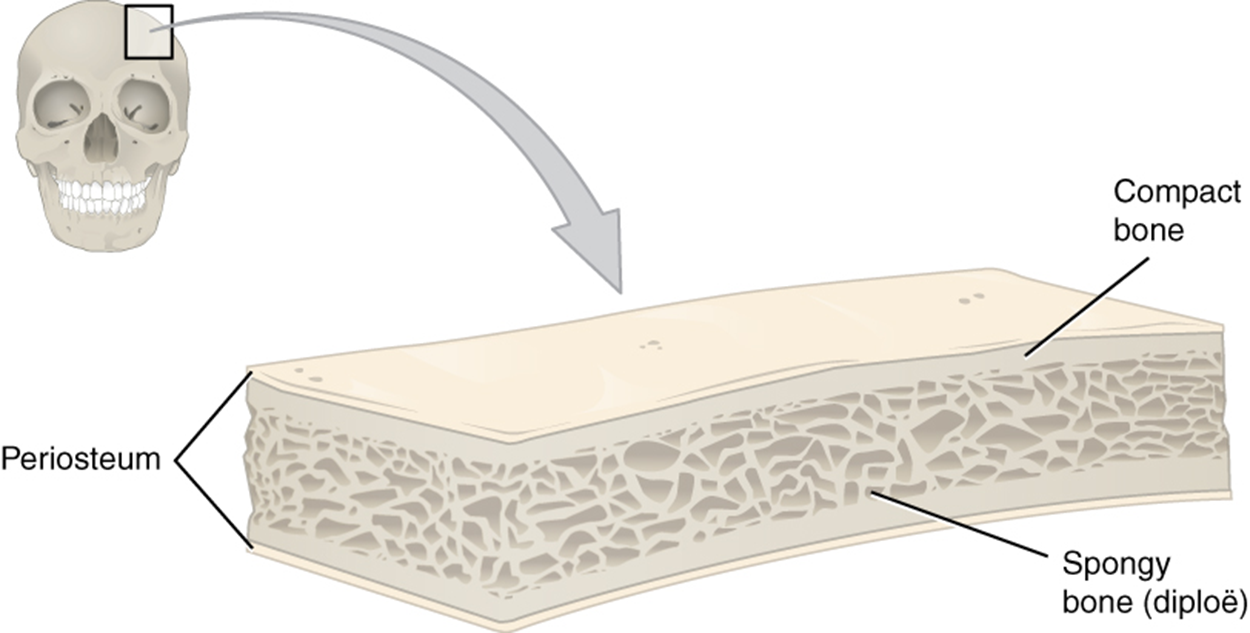

Flat bones, like those of the cranium shown in the image below, consist of a layer of diploë (spongy bone), lined on either side by a layer of compact bone. The two layers of compact bone and the interior spongy bone work together to protect the internal organs. If the outer layer of a cranial bone fractures, the brain is still protected by the intact inner layer.

| Projection | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Trochanter | Large, rough projection | Trochanter of femur |

| Tubercle | Small, rounded projection | Tubercle of humerus |

| Spine | Sharp projection | Ischial spine |

| Depression | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fossa | Shallow depression | Mandibular fossa |

| Sulcus | Groove | Sigmoid sulcus of the temporal bones |

| Fissure | Slit through bone | Auricular fissure |

| Foramen | Hole through bone | Foramen magnum in the occipital bone |

| Sinus | Air-filled space in bone | Nasal sinus |

| Articulation Markings | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Head | Prominent rounded surface | Head of femur |

| Facet | Flat surface | Vertebrae |

| Condyle | Rounded surface | Occipital condyles |

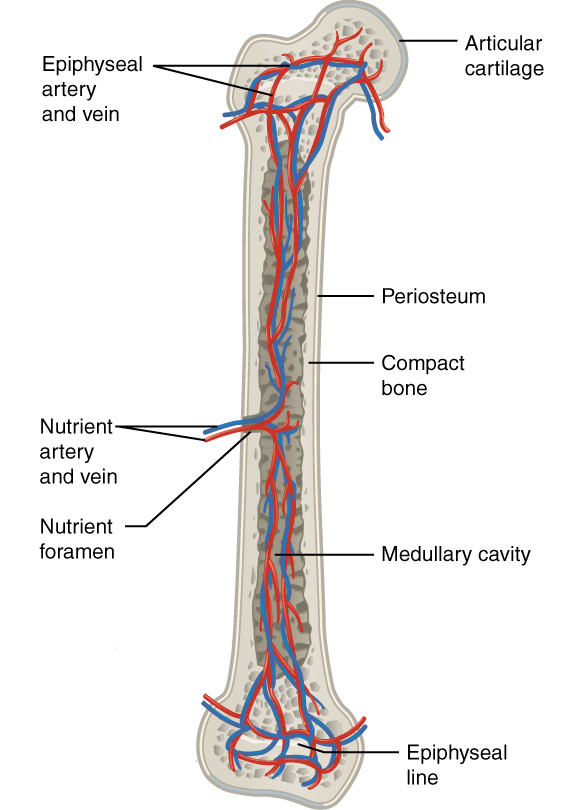

Bone tissue receives nourishment from arteries that pass through the bone matrix. The arteries enter through the nutrient foramen (plural, foramina), small openings in the bone. Nutrients diffuse through bone marrow or canals in the bone matrix to reach bone cells. As wastes are generated, they are collected by veins which then pass out of the bone through the same foramina. The epiphysis contains its own series of blood vessels which enter through a separate foramen. In adults, these blood vessel networks merge to share supply between all portions of the bone.

In addition to the blood vessels, nerves follow the same paths into the bone where they tend to concentrate in the more metabolically active regions of the bone. The nerves sense pain, and it appears the nerves also play roles in regulating blood supplies and in bone growth, hence their concentrations in metabolically active sites of the bone.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT HTTPS://OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.