Table of Contents |

Scientific theories are sets of propositions that help us understand how things work, but they are not always infallible, particularly in the social sciences. We may have infallible theories in chemistry or physics, but humans are so complicated it is nearly impossible to have a “perfect” theory for understanding or predicting behavior. However, the basic propositions of goal theory are one of the strongest theories in organizational behavior. Furthermore, the recommendations from goal theory are used in almost every industry and every organization. Goal theory states that people will perform better if they have explicit goals that are specific, have the right degree of difficulty, and are agreed to by both the manager and the employee.

The first and most basic premise of goal theory is that people are more likely to achieve those goals they intend to achieve. Thus, if we intend to do something (like get an A on an exam), we will exert more effort than we would if we take the test and hope for the best. Without a goal, our effort at the task (studying, in this case) is lower. This doesn’t mean that people without goals are unmotivated. It simply means that people with goals are more motivated. The intensity of their motivation is greater, and they are more directed.

EXAMPLE

Have you ever adopted an exercise routine, such as running or aerobics? If so, you probably set goals for yourself (like, I will run for five kilometers every other day, or do aerobics for 20 minutes, five times a week). Without goals like these, your efforts are likely to be lower; you exercise when you feel like it and quit when you tire of it.The second basic premise is that challenging but attainable goals result in better performance than easy goals. This does not mean that challenging goals are always achieved, but our performance will usually be better when we intend to achieve harder goals. Challenging goals cause us to exert more effort, and this almost always results in better performance. It is important to note here, goals must be attainable or possible to achieve, but not too easy, either. For example, if I am 5’2” and my goal is to become a WNBA (Women’s National Basketball Association) player, not only is this difficult, but probably impossible. However, could I have a goal of playing recreationally in a city league? Yes, that is difficult, but also attainable.

EXAMPLE

You may set your goal as being able to run a marathon (about 42 km), which is quite ambitious. When the big day comes, you struggle to finish and end up settling for a half marathon. However, this is far more than you ever thought possible, and further than you would have run without such a difficult goal.Another premise of goal theory is that objective, measurable goals are better than subjective or vague goals. Managers should set specific goals in terms of revenue generated, parts assembled, or whatever is an appropriate measure for the role.

EXAMPLE

Suppose you consult with a trainer at your gym, who tells you to incorporate weight lifting into your weekly routine. You would probably ask them which weight machines are best for somebody in your condition, how much weight to use, how many reps, and how many times a week will help you tone up while avoiding injury. If the trainer just tells you to “vary your exercises” and “work out until you feel the burn,” you’re no better off than you were without a trainer. A good trainer will, of course, give you a detailed plan, even a schedule, complete with specific exercises and notes on how much time or repetitions you should spend on each exercise. The advantage of specificity is that at the end of your workout, you know without any question that you met the goal. If the goal isn’t specific, it is hard to know if you achieved it or not.A key premise of goal theory is that people must agree with the goal and desire to meet it. Usually we set our own goals. But sometimes others set goals for us. This happens in work organizations quite often. Supervisors give orders that something must be done by a certain time. The employees may fully understand what is wanted, yet if they feel the order is unreasonable or impossible, they may not exert much effort to accomplish it. It may be that the goal is not aligned with, or is even at odds with, their intrinsic motivation. For example, a college professor told to excel in student evaluations may feel their real goal, to educate students, is compromised by the need to have students “like” them. Thus, it is important for people to accept the goal. They need to feel that it is also their goal. If they do not, goal theory predicts that they won’t try as hard to achieve it.

EXAMPLE

Suppose a doctor recommends more exercise to improve your cholesterol levels, and even gives you a set of recommended exercises to do several times a week. If you don’t really enjoy the exercise or have intrinsic motivation, you are not likely to keep the routine, even if you understand the importance of it to your health. However, if there is an activity that gets your heart rate up and which you enjoy, like playing in a sports league, you will accept the goal.Goal commitment is the degree to which we dedicate ourselves to achieving a goal. Goal commitment is about setting priorities. We can accept many goals (save money, eat fewer trans fats, exercise more), but we often end up doing only some of them. In other words, some goals are more important than others. And we exert more effort for certain goals.

EXAMPLE

You may have goals to exercise more and eat better, but find the second goal much harder to keep. Some exercise is kind of fun, but you just don’t like quinoa and cauliflower as much as hamburgers and french fries.This also happens frequently at work. Some goals find us more committed than others. Some people might enjoy the customer-facing parts of their job but find the record-keeping aspects tedious and hard to commit to. It’s more exciting to pilot a new project than to take on one that’s fully established, even if it’s a steady source of revenue. This is why it’s important for managers to work with employees on setting goals that they can commit to. We will look more at this in the next section.

Allowing employees to participate in setting their own goals often results in higher goal commitment. One reason is acceptance. If the employee has agreed to the goals, they will feel more ownership and be more accountable. Another reason is better tailoring of the goals to the employee’s intrinsic motivation. When employees participate in the goal-setting process, they will make sure the goal is personally interesting, challenging, and attainable. For this reason, managers should try to include the employee whenever possible.

EXAMPLE

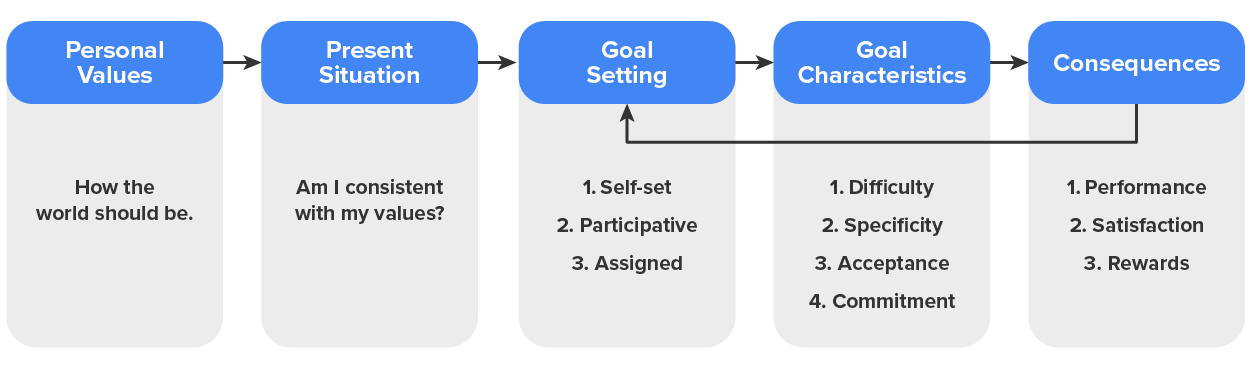

Randi is a word processing specialist at a law firm; her job requires typing and formatting legal documents, frequently from dictated recordings. Randi has a reputation for excellence in terms of quantity (nobody is faster at producing documents), but there is some concern about quality (the cost of her efficiency is that more typos and formatting errors are in her documents). She is in her annual performance review meeting with her manager, which includes goal setting.One basic goal-setting model is shown below. The process starts with our values. Values are our beliefs about how the world should be and often include words like “should” or “ought.” Next, we compare our present situation against these values. Working with a manager, we might have three kinds of goals.

| Type of Goal | Explanation | Example | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-set goals | The goals the employee sets for themselves. | Randi has an average of 10 pages typed and formatted in an hour. Because she enjoys the challenge and reputation of being “the fastest word processor in the West,” she wants to bring her average to 12 pages per hour. | A 20% increase in productivity for Randi (12 pages instead of 10) is appropriately difficult and challenging but attainable. It is also specific (an objective goal that can be measured), accepted (it is her idea), and has a high commitment (she enjoys the challenge). |

| Participative goals | These are jointly set between manager and employee. They may be negotiated, if the manager feels they are more important than the employee. | Randi’s manager wants to focus more on the quality of output. It’s extremely important that legal documents be “perfect,” or as close to it as they can. | Together, Randi and her manager set a specific goal of lowering Randi’s error rate to 50% of what it is currently; it is difficult but not impossible (like striving for absolute perfection). Randi accepts this because she knows it is important; she is committed because she knows her impressive speed is not as valuable if others need to spot-check her work. |

| Assigned goals | These are goals the manager, or even the organization, assigns. | Her manager also assigns Randi a review of the firm’s style guidelines and to pass a series of tests to prove her competence. Randi has taken these tests before, but the manager thinks a refresher will do her good. | The manager might raise the stakes by asking Randi to get a perfect score on every test. This is a specific measure, and the challenge could help Randi accept and commit to the assigned goal. |

The process of setting goals and evaluating outcomes is illustrated below. As you can see, these goals should be grounded in our values and the present situation (identifying deficits between the two). We then enter a loop of setting goals that meet our criteria and regularly evaluating outcomes to either revise our goals or set new goals.

Click image to open an enlarged view

EXAMPLE

Randi takes pride in her speedy work, but her personal value is that the work the firm does is important and her work reflects the quality of the firm. Little mistakes can disrupt entire cases! So the attention to reduce her error rates is consistent with her values, even if it’s less personally satisfying than speedy work. The set of goals include the right amount of difficulty, specific and measurable goals, acceptance by Randi, and her commitment. The consequence of reaching her goal will be that Randi will be satisfied with herself; her work will be more consistent with her values. She’ll be even more satisfied if her supervisor praises her performance and gives her a promotion.Goal theory can be a tremendous motivational tool. In fact, you may have experienced this at a job—setting goals with your manager and listing the specific details.

Despite its many strengths, there are some cautions to keep in mind. Researcher Edwin Locke has identified some of them.

First, setting goals in one area can lead people to neglect other areas. In our example, if Randi prioritizes her training over urgent firm needs, it’ll overshadow her work. Or perhaps she has minor tasks that aren’t included in her performance review, like documenting her time spent on various projects for billing purposes. If she neglects this, the firm loses money. It is important to set goals for all major duties; these duties may include ones that are minor in terms of time and challenge but very important overall.

Second, goal setting sometimes has unintended consequences. For example, employees might set easy goals so that they look good when they achieve them. Or the goals may cause unhealthy competition between employees; for example, if two sales associates set the goal of being “the leader,” they cannot both achieve this, and it might get ugly. Another unwanted consequence is an employee getting demotivated when they fall short of their goal. Managers can remedy this by remembering to:

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR". ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ORGANIZATIONAL-BEHAVIOR/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.