Table of Contents |

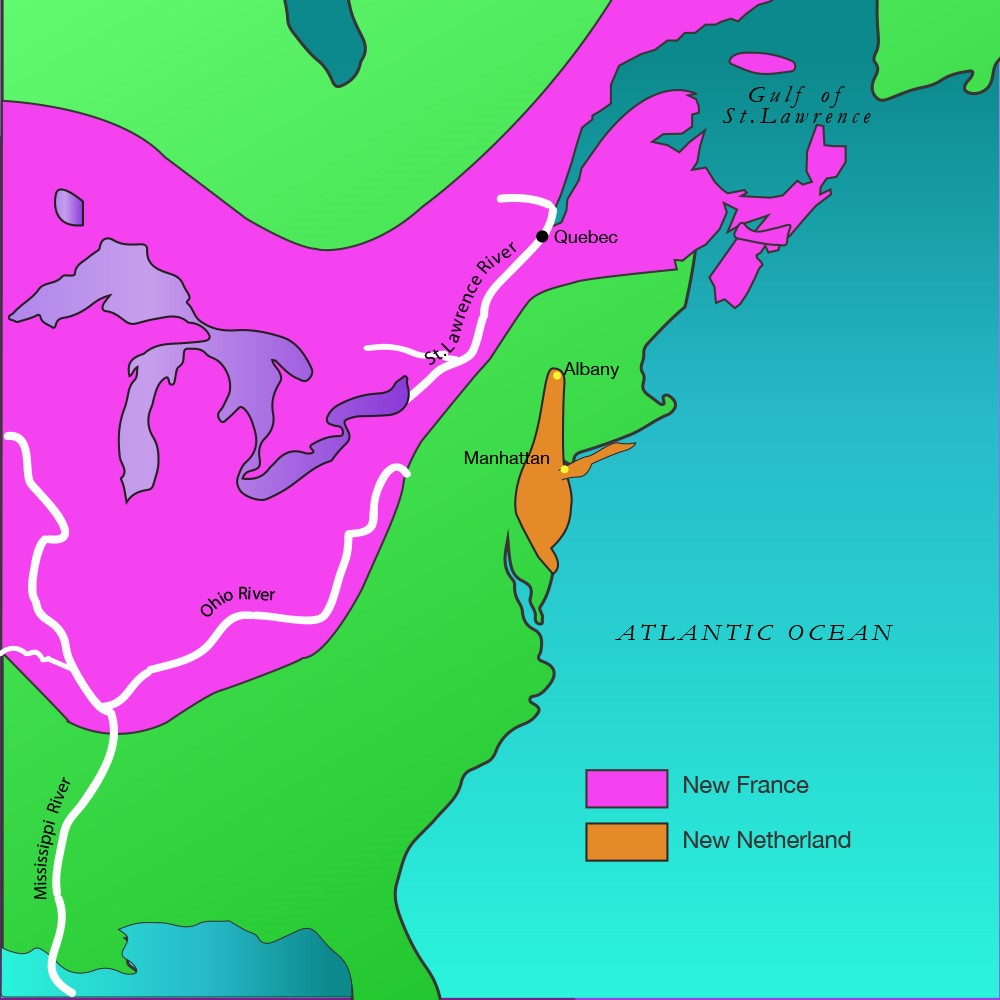

Seventeenth-century French and Dutch colonies in North America were modest in comparison to Spain’s colossal global empire. New France and New Netherland remained small commercial operations focused on the fur trade and did not attract an influx of migrants.

The Dutch in New Netherland confined their operations to Manhattan Island, Long Island, the Hudson River Valley, and what later became New Jersey. Dutch trade goods circulated widely among the Native Americans in these areas, and they also traveled well into the interior of the continent along preexisting native trade routes.

French habitants, or farmer-settlers, eked out an existence along the St. Lawrence River. French fur traders and missionaries, however, ranged far into the interior of North America, exploring the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi River. These pioneers gave France somewhat inflated imperial claims to lands that nonetheless remained firmly under the dominion of Native American groups.

Spanish exploits in the New World whetted the appetite of other would-be imperial powers, including France. Like Spain, France was a Catholic nation and committed to expanding Catholicism around the globe. Unlike Spain, however, the French monarchy took little interest in sponsoring expeditions to the New World. Thus, the burden of exploring and claiming portions of North America fell upon individual explorers and French Jesuit missionaries.

From 1534 to 1541, Jacques Cartier made three voyages of discovery on the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River. Like other European explorers, Cartier made exaggerated claims of mineral wealth in America, but he was unable to send great riches back to France. Because of the resistance from Native Americans as well as his own lack of planning, he could not establish a permanent settlement in North America.

French explorer Samuel de Champlain occupies a special place in the history of the Atlantic World for his role in establishing a permanent French presence in the New World. Champlain explored the Caribbean in 1601 and then the coast of New England in 1603 before traveling farther north. In 1608, he traveled up the St. Lawrence River and founded Quebec. Thereafter, he made numerous Atlantic crossings as he worked tirelessly to promote settlement in New France.

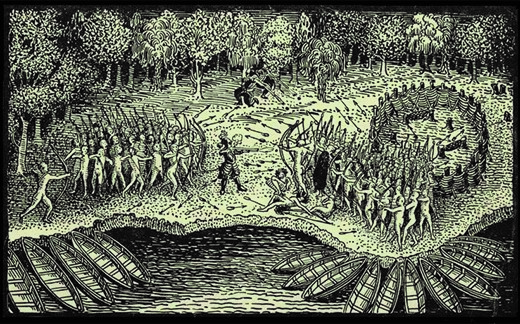

Unlike Spanish conquistadores, French explorers, especially Champlain, fostered alliances and commercial relationships with a variety of native tribes. These alliances paved the way for French exploration further into North America, specifically into areas around the Great Lakes, areas around Hudson Bay, and eventually down the Mississippi River to the port of New Orleans. For instance, Champlain made an alliance with the Huron Confederacy and the Algonquins and agreed to fight with them against their enemy, the Iroquois.

The French were primarily interested in establishing commercially viable colonial outposts, and to that end, they created extensive trading networks in New France. These networks relied on native hunters to harvest furs, especially beaver pelts, and to exchange these items for French glass beads and other trade goods.

These networks promoted more cooperative and beneficial relationships with Native Americans than was practiced among the Spanish or the English. For instance, many French fur traders married native women, and the offspring from these relationships were known as Métis. Many Métis became guides, traders, and interpreters within New France.

The French also sought to replicate the wealth of Spain’s New World empire by colonizing tropical areas. The French challenged Spanish control of the Caribbean by turning their attention to small islands in the West Indies. By 1635, the French had colonized two of these islands, Guadeloupe and Martinique, and by the 1660s, they controlled part of Hispaniola (known as Saint-Domingue, or present-day Haiti). Though it lagged far behind Spain, France could now boast its own West Indian colonies. These colonial possessions became lucrative sugar plantation sites that turned a profit for French planters by relying on enslaved African labor.

In addition to French explorers or French plantation owners in the Caribbean, small numbers of Jesuit missionaries expanded the French presence in North America by attempting to convert Native Americans to Catholicism. The Jesuits were members of the Society of Jesus, an elite religious order founded in the 1540s to spread Catholicism and combat the spread of Protestantism. The first Jesuits arrived in Quebec in the 1620s, and for the next century, their numbers did not exceed 40 priests. Unlike Spanish missionaries, who attempted to gather Native Americans into enclosed missions, Jesuits lived alongside native groups. Thus, while French and Native American traders in New France labored in the fur trade, Jesuit missionaries often worked in the same villages by healing the sick and attempting to convert native peoples to Catholicism.

Jesuit missionaries wrote detailed annual reports about their progress in bringing the Christian faith to the Algonquian, Huron, and Iroquois tribes. These reports are known as the Jesuit Relations, and they provide a rich source for understanding both the Jesuit view of the Native Americans and the Native American response to the colonizers.

The Jesuit Relations were sold and distributed throughout France as a way to fund further Jesuit missions into the New World. Because of their intent and perspective, these primary sources provide historians with an account of France’s colonizing project from the French perspective. They not only give us insights into the religious views of the French Jesuits themselves but also an inside view of how French colonizers viewed the people they encountered. As a result, French assumptions about morality, what a proper government should look like, and appropriate social interactions are written throughout these documents. While many of the authors described the culture, customs, and beliefs of native tribes, such as the Iroquois and the Algonquins, they almost always did so within the French worldview.

The Jesuit Relations

Here is an excerpt from a letter written by Father Pierre Biard to the Reverend Christopher Baltazar in Paris (1611):

“The nation is savage, wandering and full of bad habits; the people few and isolated. They are, I say, savage, haunting the woods, ignorant, lawless and rude: they are wanderers, with nothing to attach them to a place, neither homes or relationship, neither possessions nor love of country; as a people they have bad habits, are extremely lazy, gluttonous, profane, treacherous, cruel in their revenge, and given up to all kinds of lewdness, men and women alike, the men having several wives and abandoning them to others, and the women only serving them as slaves, whom they strike and beat unmercifully, and who dare not complain; and after being half killed, if it so please the murderer, they must laugh and caress him.

With all these vices, they are exceedingly vainglorious: they think they are better, more valiant and more ingenious than the French; and, what is difficult to believe, richer than we are. They consider themselves, I say, braver than we are, boasting that they have killed Basques and Malouins, and that they do a great deal of harm to the ships, and that no one has ever resented it, insinuating that it was from a lack of courage. They consider themselves better than the French: "For," they say. "You are always fighting and quarreling among yourselves; we live peaceably. You are envious and are all the time slandering each other; you are thieves and deceivers; you are covetous, and are neither generous nor kind; as for us, if we have a morsel of bread we share it with our neighbor."

They are saying these and like things continually, seeing the above-mentioned imperfections in some of us, and flattering themselves that some of their own people do not have them so conspicuously, not realizing that they all have much greater vices, and that the better part of our people do not have even these defects, they conclude generally that they are superior to all Christians...they see many faults; considering neither the virtues of the other Catholics, nor their own still greater imperfections; wishing to have, like Cyclops, only a single eye, and to fix that one upon the vices of a few Catholics, never upon the virtues of the others, nor upon themselves, unless it be for the purpose of self-deception.”

Meanwhile, the entrance of the Netherlands into the Americas is part of a larger story of religious and imperial conflict in Europe. In the 1500s, Calvinism, one of the major Protestant reform movements, had found adherents in the northern provinces of the Spanish Netherlands. During the 16th century, these provinces began a long struggle to achieve independence from Catholic Spain. Established in 1581 but not recognized as independent by Spain until 1648, the Dutch Republic, or Holland, quickly made itself a powerful force in the race for Atlantic colonies and wealth.

The Dutch distinguished themselves as commercial leaders in the 17th century, and, unlike the French or the Spanish, their mode of colonization relied on powerful corporations: the Dutch East India Company, chartered in 1602 to trade in Asia, and the Dutch West India Company, established in 1621, to colonize and trade in the Americas.

While employed by the Dutch East India Company in 1609, English sea captain Henry Hudson explored New York Harbor and the river that now bears his name. Like many explorers of the time, Hudson was actually seeking a northwest passage to Asia and its wealth, but the ample furs harvested from the region he explored, especially the coveted beaver pelts, provided a reason to claim it for the Netherlands. The Dutch named their colony New Netherland, and it served as a fur-trading outpost for the expanding and powerful Dutch West India Company.

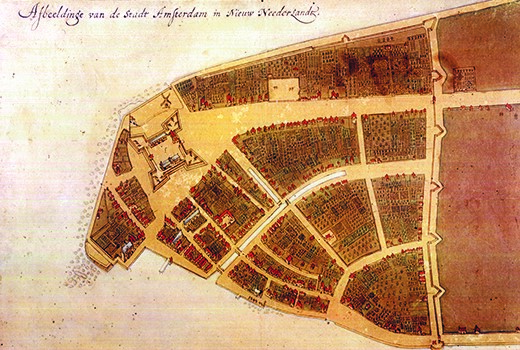

Peter Stuyvesant, one of the Dutch directors general of the North American settlement, served from 1647 to 1664. Stuyvesant expanded the fledgling outpost of New Netherland east to present-day Long Island and for many miles north along the Hudson River. The resulting elongated colony served primarily as a fur-trading post, with the powerful Dutch West India Company controlling all commerce. Fort Amsterdam, on the southern tip of Manhattan Island, defended the growing city of New Amsterdam.

With headquarters in New Amsterdam on the island of Manhattan, the Dutch set up several regional trading posts, including one at Fort Orange—named for the royal Dutch House of Orange-Nassau—in present-day Albany. A brisk trade in furs with local Algonquian and Iroquois peoples brought the Dutch and native peoples together in a commercial network that extended throughout the Hudson River Valley and beyond.

During the summer trading season, Native Americans gathered at trading posts, such as Fort Orange, where they exchanged furs for guns, blankets, and alcohol. The furs, especially beaver pelts destined for the lucrative European millinery market, would be sent down the Hudson River to New Amsterdam. There, enslaved or free workers would load them aboard ships bound for Amsterdam.

In 1655, Stuyvesant took over the small outpost of New Sweden along the banks of the Delaware River, in present-day New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. He also defended New Amsterdam from Native American attacks by ordering enslaved Africans to build a protective wall on the city’s northeastern border.

New Netherland failed to attract many Dutch colonists, however. By 1664, only 9,000 people were living there. Conflict with native peoples, as well as dissatisfaction with the Dutch West India Company’s trading practices, made the Dutch outpost an undesirable place for many migrants.

The small size of the population meant a severe labor shortage. To complete the arduous tasks of early settlement, the Dutch West India Company forcibly imported some 450 enslaved Africans between 1626 and 1664. (The company had involved itself heavily in the trade of enslaved people, and in 1637, it captured Elmina, the trading post on the west coast of Africa, from the Portuguese.) The shortage of labor also meant that New Netherland welcomed non-Dutch immigrants, including Protestants from Germany, Sweden, Denmark, and England, and embraced a degree of religious tolerance, allowing Jewish immigrants to become residents beginning in the 1650s. Indeed, a wide variety of people lived in New Netherland from the start. One observer claimed 18 different languages could be heard on the streets of New Amsterdam.

The Dutch West India Company found the business of colonization in New Netherland to be expensive. To share some of the costs, it granted Dutch merchants who invested heavily in its patroonships or large tracts of land, as well as the right to govern the tenants there. In return, the shareholder who gained the patroonship promised to pay for the passage of at least 30 Dutch farmers to populate the colony. One of the largest patroonships was granted to Kiliaen van Rensselaer, a director of the Dutch West India Company. This patroonship covered most of present-day Albany and Rensselaer counties. This pattern of settlement created a yawning gap in wealth and status between the tenants, who paid rent, and the wealthy patroons.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents Volume 1. (n.d.). Retrieved November 14, 2016, from moses.creighton.edu/kripke/jesuitrelations/relations_01.html