Table of Contents |

Conflict is an inevitable part of human interaction, whether it occurs in the workplace, within families, or between nations. The key to successfully resolving conflicts often lies in finding common ground—a point of agreement or shared interest that can be used as a foundation for collaboration. In this lesson, we will explore strategies for identifying and building upon common ground to resolve disputes effectively. By understanding and applying these strategies, individuals involved in conflicts can move from opposition to cooperation, ultimately achieving mutually beneficial outcomes.

Common ground refers to the shared values, interests, or goals that exist between opposing parties in a conflict. It serves as the basis for constructive dialogue and collaboration. Identifying common ground helps shift the focus of the conversation from the differences and opposing views to areas where there is mutual agreement. This shared understanding forms a solid foundation for conflict resolution, enabling the parties to move forward together.

EXAMPLE

Imagine two coworkers who disagree on the best approach to complete a project. One may prefer a more traditional, step-by-step process, while the other advocates an innovative, fast-paced method. However, both colleagues share the same goal: to produce high-quality work that benefits the organization. By focusing on their mutual desire for success, they can find a way to combine their approaches and create a new plan that satisfies both perspectives.Identifying shared values is one of the most effective ways to find common ground. Even in deeply rooted conflicts, parties often share underlying values or motivations, such as the desire for safety, respect, or success. By acknowledging these shared values, parties can begin to humanize each other and recognize that, despite their differences, they are not entirely opposed.

In personal relationships, for instance, partners may disagree about specific issues like finances or household responsibilities. However, both may value trust, love, and long-term happiness. Recognizing these shared values can help the couple understand that their disagreements are not insurmountable and that they are working toward the same overarching goal of a healthy relationship.

As we’ve covered, a common mistake in conflict resolution is to focus on the positions each party holds rather than their interests. Positions are the specific demands or outcomes that individuals believe they need to win in a conflict. Interests, on the other hand, are the underlying needs or desires that motivate these positions.

EXAMPLE

In a negotiation over salary, one party may insist on a 10% raise (position), while the employer may only offer a 5% raise. However, the underlying interests might include the employee’s need for financial security and recognition and the employer’s interest in maintaining budget constraints while keeping the employee satisfied. By shifting the focus from positions to interests, both parties can explore alternative solutions, such as a smaller raise combined with additional benefits or flexible work hours, that satisfy both their interests.Remember active listening? One of the most useful strategies for finding common ground is active listening. To quickly review, active listening involves not only hearing what the other party is saying but also making a conscious effort to understand their perspective and acknowledge their emotions. Active listening helps reduce misunderstandings and fosters an environment of mutual respect, which is essential for identifying common ground.

EXAMPLE

During a team meeting, if two employees are debating the best approach to tackle a project, one might feel that their ideas are being dismissed. By practicing active listening, the other party can acknowledge the speaker’s concerns and validate their point of view, saying something like “I hear that you are concerned about meeting the deadline if we take this approach. Let’s work together to address that concern.” This response demonstrates empathy and opens the door to finding common ground.Empathy, which we’ve also covered in a previous lesson, also plays a key role in this process. By putting yourself in the other party’s shoes, you can better understand their motivations and feelings. This emotional connection can help break down barriers and foster a sense of collaboration.

Another effective strategy for finding common ground is to ask open-ended questions that encourage dialogue and exploration of the issues at hand. Rather than asking yes-or-no questions, which can shut down the conversation, open-ended questions invite the other party to share more about their perspective, needs, and interests.

For instance, instead of asking “Do you agree with this solution?” you could ask, “How do you think we can address both of our concerns in this situation?” This type of question encourages creative thinking and collaboration, which are essential for finding common ground.

Open-ended questions also help uncover deeper insights into the other party’s interests. By asking questions like “What’s most important to you in this situation?” or “How can we work together to achieve a positive outcome for both of us?” you invite the other party to share their priorities and goals, making it easier to identify areas of agreement.

Reframing is a strategy that involves changing the way a problem or conflict is viewed. By reframing the issue, you can shift the focus from the negative aspects of the conflict to potential areas of agreement. This can help the parties involved to see the conflict in a new light and identify common ground that may have been overlooked.

EXAMPLE

In a workplace dispute over workload distribution, one employee may feel overwhelmed and resentful, while another feels that they are contributing enough. Instead of framing the issue as “You’re not pulling your weight,” the problem can be reframed as “How can we better balance the workload so that we’re both able to meet our goals?” This shift in perspective turns the conflict into a collaborative problem-solving effort rather than a blame game.Reframing can also be used to highlight shared goals or values.

EXAMPLE

In a community conflict over land use, the issue could be reframed from “Should we build housing or preserve green space?” to “How can we meet the community’s housing needs while also protecting our natural environment?”Brainstorming is a collaborative technique that encourages all parties in a conflict to generate potential solutions together. By involving everyone in the process, brainstorming fosters a sense of ownership over the outcome and helps build common ground. The key to successful brainstorming is suspending judgment during the idea generation phase, allowing creative and innovative solutions to emerge.

EXAMPLE

If a group of neighbors is in conflict over parking spaces, they could brainstorm ideas to find a solution that meets everyone’s needs. Some suggestions might include creating a schedule for parking or converting part of the lawn into additional parking spaces. By working together to come up with solutions, the neighbors can find common ground and resolve the issue amicably.When brainstorming, it’s important to create an environment where all participants feel comfortable sharing their ideas without fear of criticism. This encourages open communication and helps identify areas of agreement.

Compromise is a fundamental strategy for finding common ground in conflict resolution. It involves both parties making concessions to reach a mutually acceptable solution. While the compromise may not fully satisfy each party’s demands, it allows for progress by ensuring both sides achieve some of their key objectives.

EXAMPLE

In a workplace conflict over project deadlines, one team member may want to extend the deadline to ensure higher-quality work, while another may want to stick to the original timeline. A compromise could involve extending the deadline slightly but also setting interim milestones to ensure progress. This solution meets both parties’ interests—allowing more time for quality while maintaining a sense of urgency.Flexibility is important in the process of finding common ground. Parties must be willing to adjust their positions and consider alternative solutions that may not have been initially proposed. This openness to change is key to resolving conflicts in a way that benefits everyone involved.

In some cases, parties may feel that they are at an impasse, with neither side willing to fully concede. In such situations, it can be helpful to look for a third option—a solution that neither party had initially considered but that meets the interests of both.

EXAMPLE

In a business negotiation over the price of a product, the buyer may insist on a lower price, while the seller holds firm on their asking price. A third option might involve offering a discount for bulk purchases or including additional services with the product. This creative solution allows both parties to feel that their interests have been addressed without either side feeling like they’ve “lost.”Finding a third option often requires thinking outside the box and considering possibilities that may not have been immediately apparent. This creative approach can help break through deadlock and bring parties closer together.

Overcoming barriers to common ground involves recognizing and addressing obstacles that prevent parties from reaching a shared understanding or solution. These barriers may include emotional reactions, entrenched positions, miscommunication, or a lack of trust. It’s important to identify these challenges early in the conflict resolution process to prevent escalation. Strategies such as fostering empathy, practicing active listening, and reframing the issues can help break down these barriers, allowing both parties to move past their differences and work collaboratively toward a resolution.

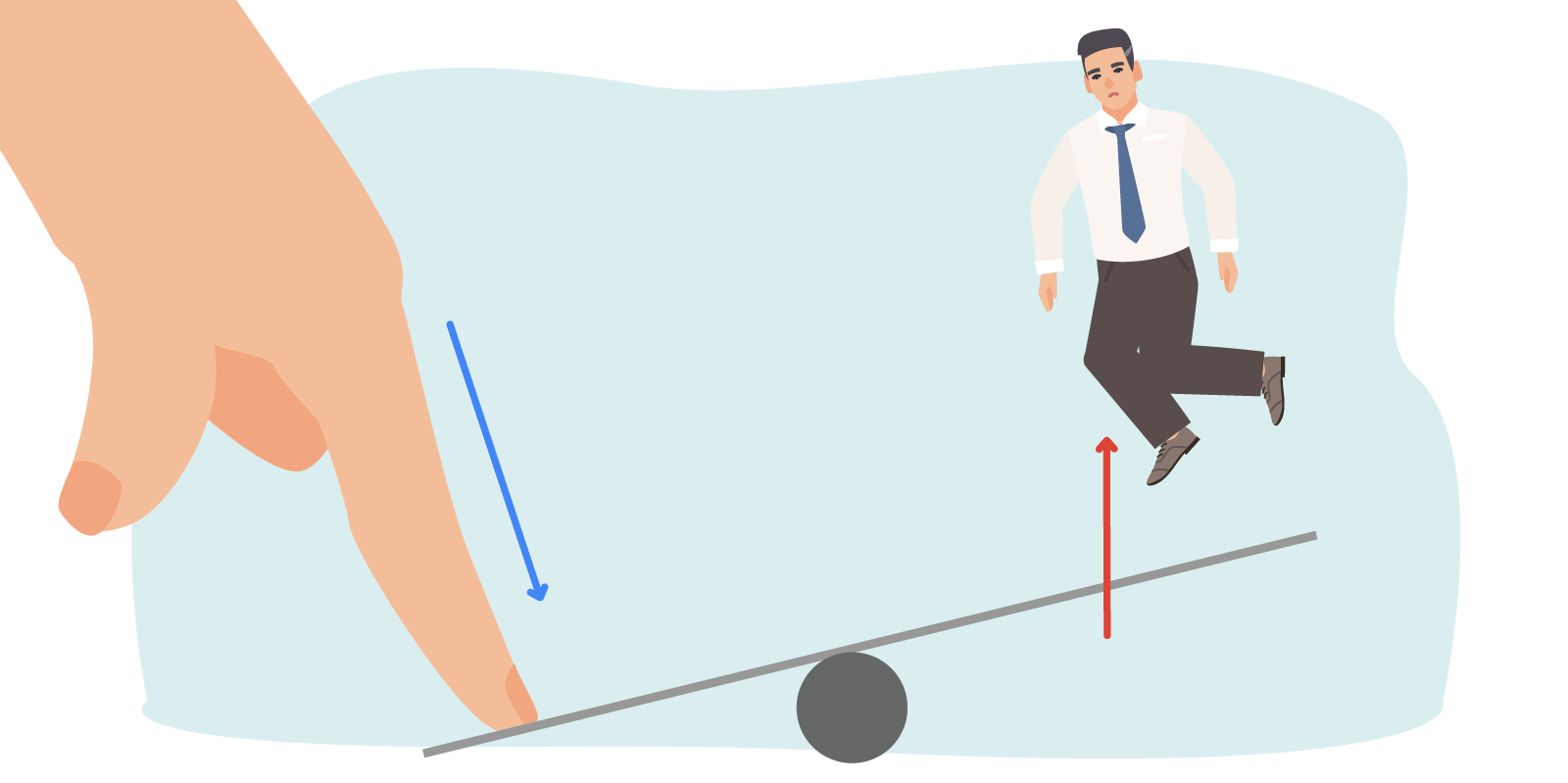

In some conflict situations, power imbalances can make it difficult to find common ground. When one party holds significantly more power—whether due to authority, resources, or influence—they may dominate the conversation or impose solutions that do not take the other party’s interests into account.

To overcome power imbalances, it’s important to empower the less powerful party by ensuring that their voice is heard and their interests are considered. This can be achieved through practicing active listening, asking open-ended questions, and creating an environment where all parties feel comfortable expressing their views.

In mediation, for instance, a skilled mediator may ensure that a less assertive party can fully articulate their concerns without being overshadowed by the more dominant party. By addressing power imbalances, mediators can help both parties feel equally valued, which is essential for finding common ground.

Attribution bias, the tendency to attribute positive traits to those we see as similar to ourselves and negative traits to those we view as different, can create significant barriers to finding common ground. In conflict situations, people may assume the worst about the other party’s motivations, which can lead to mistrust and misunderstanding.

To overcome attribution bias, it’s important to challenge assumptions and approach the conflict with an open mind. Instead of assuming the other party is acting out of malice or selfishness, parties should understand the other’s perspective by asking clarifying questions and exploring the reasons behind their actions.

EXAMPLE

In a workplace conflict, an employee may assume that their colleague is trying to sabotage their success by not collaborating effectively. However, by asking questions and seeking to understand the colleague’s perspective, the employee may learn that the colleague is simply overwhelmed with their own workload and not intentionally neglecting the team.Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY MARLENE JOHNSON (2019) and STEPHANIE MENEFEE and TRACI CULL (2024). PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.