Table of Contents |

Expectancy theory posits that we will exert much effort to perform at high levels if we believe we can obtain valued outcomes. This is different from previous theories in that expectancy theory pays more attention to how much confidence we have in ourselves and our organization that effort will lead to high performance and high performance will lead to rewards.

Expectancy theory is useful in a wide variety of situations. Choices between job offers, between working hard or not so hard, between going to work or not—virtually any set of possibilities can be addressed by expectancy theory. Basically, the theory focuses on two related issues:

Expectancy theory states that when faced with two or more alternatives, we will select the one with the most attractive expected outcome. Furthermore, the greater the attractiveness of the chosen alternative, the more motivated we will be to pursue it.

This theory has two assumptions.

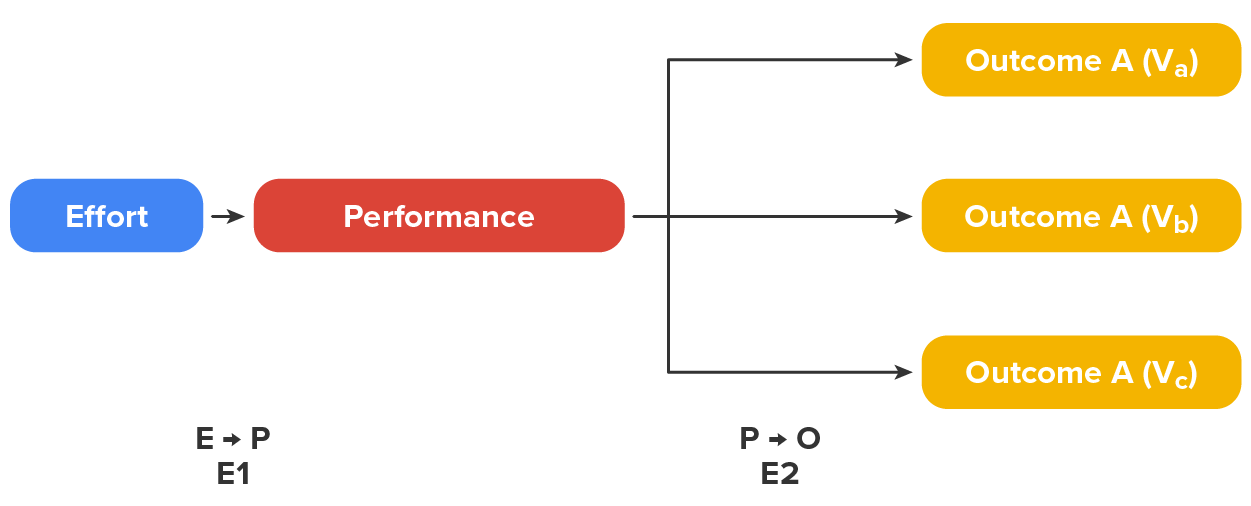

The basic model of expectancy theories has three components.

The effort-performance expectancy, abbreviated E1, is the perceived probability that effort will lead to performance (or E → P). Performance here means anything from doing well on an exam to assembling 100 toasters a day at work. Sometimes people believe that no matter how much effort they exert, they won’t perform at a high level. They have weak E1s. Other people have strong E1s and believe the opposite—that is, that they can perform at a high level if they exert high effort. People develop these perceptions from prior experiences with the task at hand (or similar tasks), and from self-perceptions of their abilities. The core of the E1 concept is that people don’t always perceive a direct relationship between effort level and performance level.

The performance-outcome expectancy, E2, is the perceived relationship between performance and outcomes (or P → O). E2 addresses the question, “What will happen if I perform well?” People with strong E2s believe that if they perform their jobs well, they’ll receive desirable outcomes—pay increases, praise from their supervisor, and a feeling that they’re really contributing. In the same situation, people with weak E2s will have the opposite perceptions—that high performance levels don’t result in desirable outcomes and that it doesn’t really matter how well they perform their jobs as long as they don’t get fired.

Valency is the degree to which one perceives an outcome as desirable. Highly desirable outcomes (such as a promotion) are positively valent. Undesirable outcomes (being disciplined) are negatively valent. Outcomes that we’re indifferent to (where you must park your car) have neutral valency. Positively and negatively valent outcomes abound in the workplace: pay increases and freezes, praise and criticism, recognition and rejection, promotions and demotions. And as you would expect, people differ dramatically in how they value these outcomes. Our needs, values, goals, and life situations affect how much valency we give an outcome. Equity is another consideration we use in determining valency. We may consider a 10% pay increase desirable until we find out that it was the lowest raise given in our work group. The model below summarizes these three core concepts of expectancy theory.

To summarize, to be motivated, an employee must:

EXAMPLE

Consider a sales team that has various bonuses and rewards for outstanding sales. The most attractive is a new car to the person with the highest sales every year; this creates an environment that is highly competitive and energized. As a new salesperson, Rocco feels that he has no chance at winning that car. The company also has a competition for first-year sales associates with a prize of a weekend vacation for two. As a new father, Rocco wouldn’t be able to take a vacation without unpleasant options (e.g., taking the baby with them, leaving her in care of relatives). Finally, they give a year-end bonus based on meeting modest goals.Why might an employee perceive that positive outcomes are not associated with high performance? Or that negative outcomes are not associated with low performance? That is, why would employees develop weak E2s? This happens for a number of reasons. One is that many organizations subscribe too strongly to a principle of equality (not to be confused with equity). They give all of their employees equal salaries for the same jobs, equal pay increases every year (these are known as across-the-board pay raises), and equal treatment wherever possible. Equality-focused organizations reason that some employees “getting more” than others leads to disruptive competition and feelings of inequity. Unions, for example, focus on creating equity, like across-the-board pay increases, because they are focused on fairness and equity. However, this might not be motivating, according to expectancy theory.

In time, employees in equality-focused organizations develop weak E2s because no distinctions are made for differential outcomes. If all employees are paid the same, in time, most will decide that it isn’t worth the extra effort to be a high performer. Needless to say, this is not the goal of competitive organizations and can cause the demise of the organization as it competes with other firms in today’s global marketplace.

Expectancy theory states that to maximize motivation, organizations must make outcomes contingent on performance. This is the main contribution of expectancy theory: It makes us think about how organizations should distribute outcomes. From expectancy theory, we know that employees will see no difference in outcomes for good and poor performance, so they will not have as much incentive to be good performers. Effective organizations need to actively encourage the confidence that good performance leads to positive outcomes (bonuses, promotions) and that poor performance leads to negative ones (discipline, termination). Remember, there is a big difference between treating employees equally and treating them equitably. However, oftentimes employees like the ability to depend on regular pay increases. In order to balance this approach, many companies will offer a baseline annual pay increase to everyone, say a 5% increase, and a higher increase to those meeting certain criteria.

What if an organization ties positive outcomes to high performance and negative outcomes to low performance? Employees will develop strong E2s. But will this result in highly motivated employees? The answer is maybe. We have yet to address employees’ E1s. If employees have weak E1s, they will perceive that high (or low) effort does not result in high performance and thus will not exert much effort. It is important for managers to understand that this can happen despite rewards for high performance.

Task-related abilities are probably the single biggest reason why some employees have weak E1s. Self-efficacy is our belief about whether we can successfully execute some future action or task or achieve some result. High self-efficacy employees believe that they are likely to succeed at most or all of their job duties and responsibilities. And as you would expect, low self-efficacy employees believe the opposite. Specific self-efficacy reflects our belief in our capability to perform a specific task at a specific level of performance.

EXAMPLE

If our car salesman Rocco believes that the probability of selling at least one car per month is 90%, his self-efficacy for this task is high. Specific self-efficacy is more variable than permanent qualities of personality. For example, Rocco may feel a lot more confident in summer that he can sell cars than in the winter, when fewer people walk in the door.There is little doubt that our own beliefs are some of the most powerful motivators of behavior. Our efficacy expectations at a given point in time determine not only our initial decision to perform (or not perform) a task, but also the amount of effort we will expend and whether we will persist in the face of adversity. Self-efficacy has a strong impact on the E1 factor. As a result, self-efficacy is one of the strongest determinants of performance in any particular task situation.

Organizations exert tremendous influence over employee choices in their performance levels and how much effort to exert on their jobs. That is, organizations can have a major impact on the direction and intensity of employees’ motivation levels. Practical applications of expectancy theory include:

| Motivational Improvement | Strategies |

|---|---|

|

Strengthening E1 (effort → performance expectancy) |

|

|

Strengthening E2 (performance → outcome expectancy) |

|

More so than any other motivation theory, expectancy theory can be tied into most concepts of what and how people become motivated. Consider the following examples.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR". ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ORGANIZATIONAL-BEHAVIOR/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.