Table of Contents |

Despite the Constitution’s stated division of power between the national government and the states, as well as early Supreme Court decisions that clarified the scope of national power, the nature of American federalism continues to evolve. Since the country’s inception, the changing social, political, and economic landscape has shifted the balance of power in one direction or another.

Leading up to the present, two factors contributed to the evolution of federalism. First, the Supreme Court has often weighed in on the issue of state and national power, as it rules on cases that involve the states and national government. Second, as the United States evolved from an agricultural nation to one whose economy is based primarily on industrial capitalism, the federal system adapted to provide for the new expectations of the people.

Following the Civil War, the rulings of the Supreme Court blocked attempts by both state and federal governments to expand their authority. As a result, the United States maintained a system known as dual federalism, in which the states and national government exercise exclusive authority in distinct spheres of jurisdiction. Dual federalism is often compared to a layer cake. Like the layers of a cake, the levels of government do not blend with one another but instead are clearly defined.

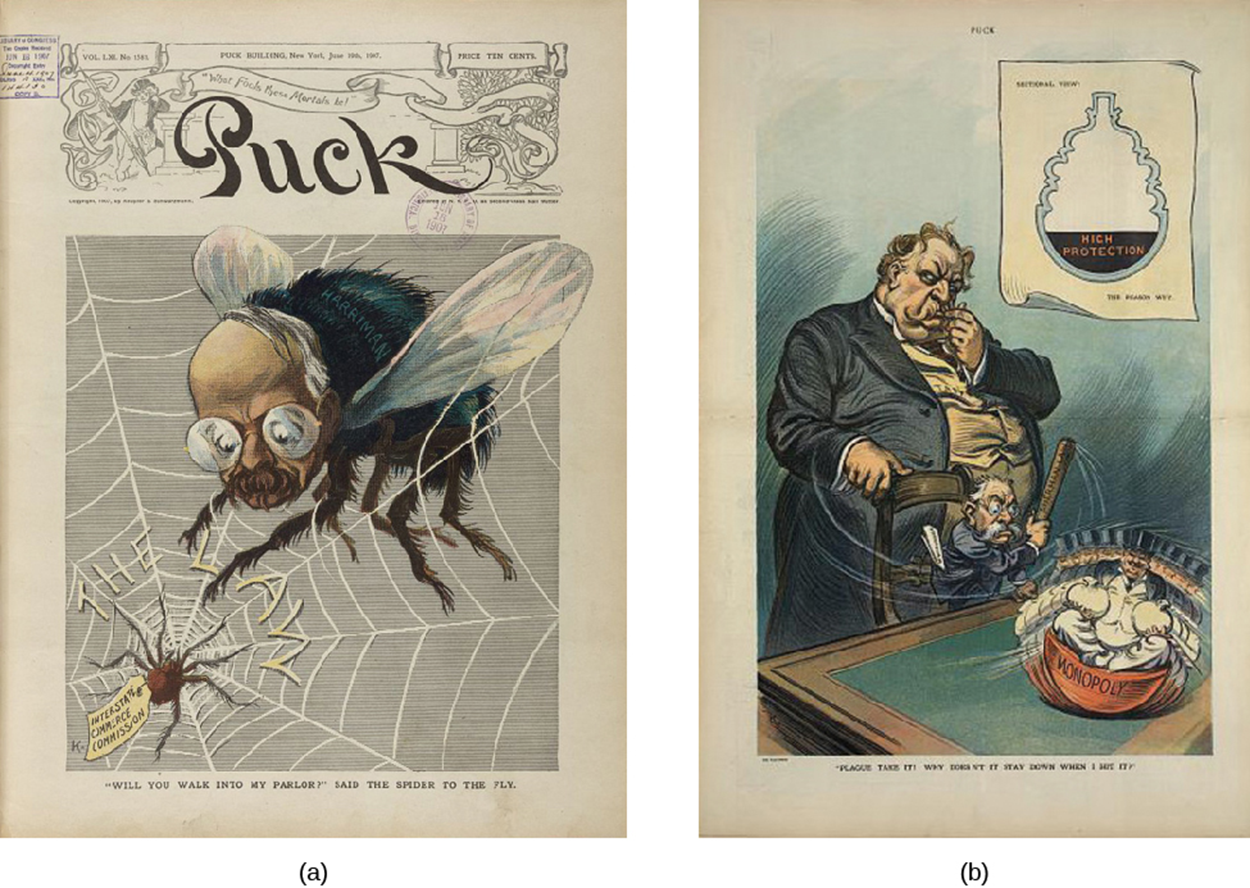

As the American economy grew more industrialized and complex, the U.S. government attempted to intervene for the benefit of consumers and small businesses. In the late nineteenth century, companies began to grow and establish monopolies. One company might control an entire industry, or they might conspire with other large companies to control the market for an entire industry together. These monopolies could then control prices for their products: raising the price to gain more profit or lowering the price so that smaller companies in the industry could not afford to stay in business.

IN CONTEXT

Monopolies, and trusts consisting of several large industries, are still a problem today. In 2020, the Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against tech giant Google, after Google signed a deal with another tech giant Apple so that Apple’s iPhone Safari browser would use the Google search engine. In this way, Google gained more control of the search engine market, which it can then use to control the price of online advertising, wipe out competition from businesses that compete with Google in other markets, and generally control the flow of information.

In 1895, in United States v. E. C. Knight, the Supreme Court ruled that the national government lacked the authority to regulate manufacturing. The case came about when the government, using its regulatory power under the Sherman Act, attempted to override American Sugar’s purchase of four sugar refineries, which would give the company a large share of the industry. Distinguishing between commerce among states and the production of goods, the court argued that the national government’s regulatory authority applied only to commercial activities. If manufacturing activities fell under the commerce clause of the Constitution, then “comparatively little of business operations would be left for state control,” the court argued.

This decision slowed the expansion of federal authority made possible through the commerce clause. The ruling was reversed in 1937, in N.L.R.B. v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., when the Supreme Court ruled that manufacturing could be subject to federal regulation if it related to business dealings across states.

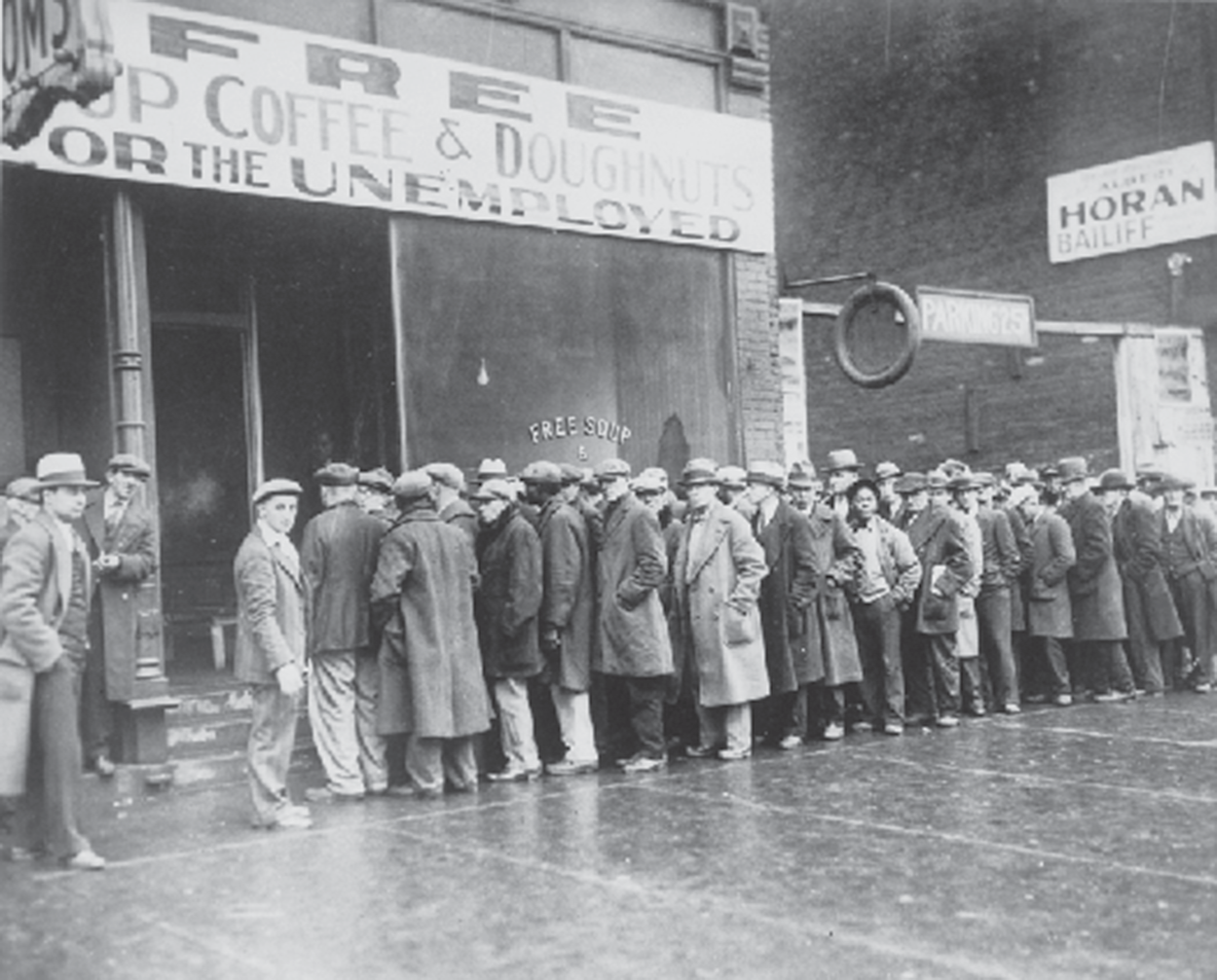

Industrialization brought about economic changes that raised questions about the balance of power between state and national government. Industrialization also brought about dramatic social and geographic changes, such as the creation of large urban populations. As the economy shifted, and the needs of the people changed over time, so did the relationship between the national government and the states. In the early twentieth century, a new model of federalism emerged, called cooperative federalism.

The first event to bring about this major shift in federalism was the Great Depression.

Cooperative federalism was born of this necessity, and lasted well into the twentieth century, as the national and state governments each found it beneficial. Under this model, both levels of government coordinated their actions to solve national problems.

In contrast to dual federalism, cooperative federalism erodes the jurisdictional boundaries between the states and national government, so that they can both carry out policies in the same areas, such as social welfare and education. Whereas dual federalism is compared to a layer cake, cooperative federalism is often compared to a marble cake, with a blending of layers of cake—or government (Figure 3). The era of cooperative federalism contributed to the gradual expansion of national authority into the jurisdictional domain of the states, as well as to the expansion of the national government’s power in concurrent policy areas.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed a series of programs, known as the New Deal, as a means to tackle the Great Depression.

In the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson’s administration further expanded the national government’s role in society through a host of new programs (Table 1). These programs strengthened the U.S. social safety net and provided more benefits to the needy. They also poured resources into education, usually a policy area reserved for states, and advanced civil rights (Figure 4).

Table 1 Great Society Programs

| Policy Area | Programs |

|---|---|

| Health | Medicaid (which provides medical assistance to the indigent), Medicare (which provides health insurance to the elderly and some people with disabilities), and school nutrition programs were created. |

| Education | The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965), the Higher Education Act (1965), and the Head Start preschool program (1965) were established to expand educational opportunities and equality. |

| Consumer Protection | The Clean Air Act (1965), the Highway Safety Act (1966), and the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act (1966) promoted environmental and consumer protection. |

| Housing | Laws were passed to promote urban renewal, public housing development, and affordable housing. |

| Civil Rights | In addition to these Great Society programs, the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965) gave the federal government effective tools to promote equality in civil rights across the country. |

While the era of cooperative federalism witnessed a broadening of federal powers in concurrent and state policy domains, it is also an era of deepening coordination between the states and the federal government in Washington.

Nowhere is this clearer than with respect to the social welfare and social insurance programs created during the New Deal and Great Society eras, most of which are jointly administered and funded by both state and federal authorities. The Social Security Act of 1935 gave state and local officials wide discretion over eligibility and benefit levels. It created federal subsidies for state-administered programs for the elderly, people with disabilities, dependent mothers, and children. The unemployment insurance program, also created by the Social Security Act, requires states to provide jobless benefits. However, it allows the states significant latitude to decide the level of tax to impose on businesses in order to fund the program, as well as the duration and replacement rate of unemployment benefits. A similar multilevel division of labor governs Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance.

The era of cooperative federalism left two lasting attributes of federalism in the United States. First, a nationalization of politics emerged to address national problems such as marketplace inefficiencies, poverty, and social and political inequality. The nationalization process expanded the size of the federal administrative apparatus and increased the flow of federal grants to state and local authorities, which helped offset the financial costs of maintaining a host of New Deal- and Great Society-era programs. The second lasting attribute is the flexibility that states and local authorities were given in the implementation of federal social welfare programs. One consequence of administrative flexibility is cross-state differences in the levels of benefits and coverage.

During the administrations of Presidents Richard Nixon (1969–1974) and Ronald Reagan (1981–1989), attempts were made to reverse the expansion of federal authority—that is, to restore states’ prominence in policy areas into which the federal government had moved.

New federalism is the term used to describe the general attempt to decentralize policies, with the goal of enhancing administrative efficiency and reducing overall public spending. During Nixon’s administration, general revenue sharing programs were created that distributed funds to the state and local governments with minimal restrictions on how the money was spent. Reagan furthered these attempts to reduce the power of the national government. He consolidated several federal grant programs related to social welfare and reformulated them, which gave state and local administrators greater discretion in using federal funds. However, Reagan met with mixed success, as his administration encountered opposition from Democrats in Congress, moderate Republicans, and interest groups, which prevented him from making further advances on that front.

Several Supreme Court rulings also promoted new federalism by limiting the scope of the national government’s power, especially under the commerce clause. For example, in United States v. Lopez, the court struck down the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990, which banned gun possession in school zones. It argued that the regulation in question did not “substantively affect interstate commerce.” The ruling ended a nearly sixty-year period in which the court had used a broad interpretation of the commerce clause, which by the 1960s allowed it to regulate numerous local commercial activities.

Many would say that in the years since the 9/11 attacks, power has swung back in the direction of centralized federal authority.

Since the late 1990s, states have asserted a right to make immigration policy on the grounds that they are enforcing, not supplanting, the nation’s immigration laws. Some are exercising their jurisdictional authority by restricting undocumented immigrants’ access to education, health care, and welfare benefits, areas that fall under the states’ responsibilities. In 2005, twenty-five states enacted a total of thirty-nine laws related to immigration. By 2014, forty-three states and Washington, DC had passed a total of 288 immigration-related laws and resolutions. In 2020, thirty-two different states enacted a total of 206 additional measures, including many related to COVID-19.

Arizona has been one of the states challenging federal authority over immigration. In 2010, it passed Senate Bill 1070, which sought to make it so difficult for undocumented immigrants to live in the state that they would return to their native country. The federal government filed suit to block the Arizona law, contending that it conflicted with federal immigration laws. Meanwhile, people across the United States protested for and against it (Figure 5).

In 2012, in Arizona v. United States, the Supreme Court affirmed federal supremacy on immigration. The court struck down three of the four central provisions of the Arizona law.

Historically, marriage has fallen under the domain of states. In 1993, the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled that the refusal of the state to marry same-sex couples violated the states’ constitutions. In response, the federal government passed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996, stepping into this policy issue. Whereas DOMA allowed states to choose whether to recognize same-sex marriages, it also defined marriage as a union between a man and a woman, which meant that same-sex couples were denied various federal provisions and benefits—such as the right to file joint tax returns and to receive Social Security survivor benefits. By 2006, two years after Massachusetts became the first state to recognize marriage equality, twenty-seven states had passed constitutional bans on same-sex marriage. In United States v. Windsor (2012), the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government had no authority to define marriage.

However, public opinion shifted quickly. In 2015, same-sex marriage was recognized in thirty-six states, plus Washington, DC, up from seventeen in 2013. Two years later, the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that states cannot discriminate between same-sex and different-sex couples based on the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

As the immigration and marriage equality examples illustrate, constitutional disputes have arisen as states and the federal government have sought to reposition themselves on certain policy issues and as the federal courts weigh in on the disputes.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “AMERICAN GOVERNMENT 3E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/AMERICAN-GOVERNMENT-3E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.