Table of Contents |

Mature, circulating erythrocytes have few internal cellular structural components, having ejected them during development. They lack a nucleus, endoplasmic reticula, and a Golgi apparatus which means they cannot produce or process proteins or lipids. They lack mitochondria which means they rely on anaerobic respiration for ATP production and therefore, do not use any of the oxygen they transport. RBCs do, however, contain some structural proteins that help the blood cells maintain their unique structure and enable them to change their shape to squeeze through capillaries.

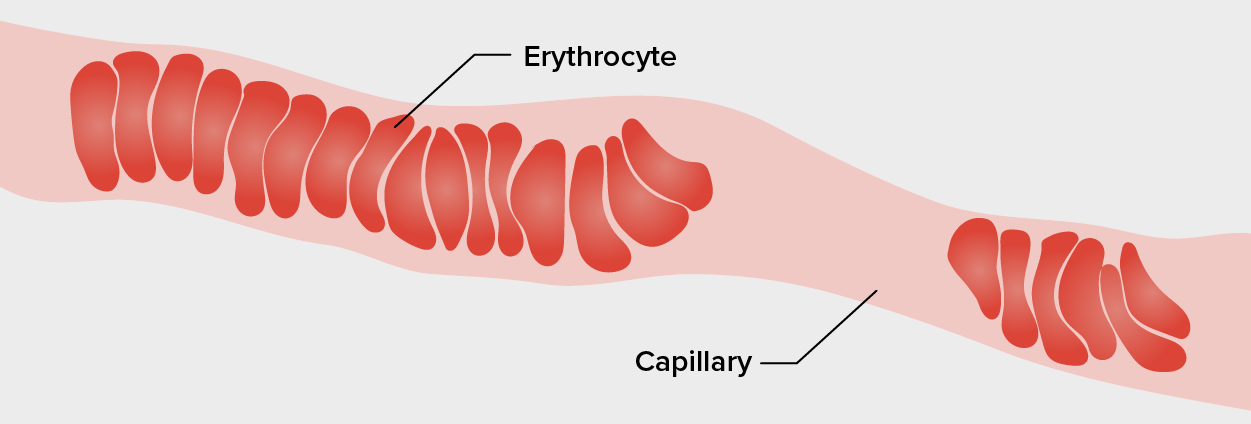

Erythrocytes have a unique shape called a biconcave disc; that is, they are plump at their periphery and very thin in the center. Since they lack most organelles, there is more interior space for the presence of the hemoglobin molecules that, as you will see shortly, transport gasses. The biconcave shape also provides a greater surface area across which gas exchange can occur, relative to its volume; a sphere of a similar diameter would have a lower surface area-to-volume ratio. In the capillaries, the oxygen carried by the RBCs can diffuse into the plasma and then through the capillary walls to reach the cells, whereas some of the carbon dioxide produced by the cells as a waste product diffuses into the capillaries to be picked up by the RBCs. Capillary beds are extremely narrow, slowing the passage of the RBCs and providing an extended opportunity for gas exchange to occur. However, the space within capillaries can be so small that, despite their own small size, RBCs may have to fold in on themselves if they are to make their way through. Fortunately, their structural proteins like spectrin are flexible, allowing them to bend over themselves to a surprising degree, then spring back again when they enter a wider vessel. In wider vessels, RBCs may stack on top of one another much like a roll of coins, forming a rouleau (plural = rouleaux), from the French word for “roll.”

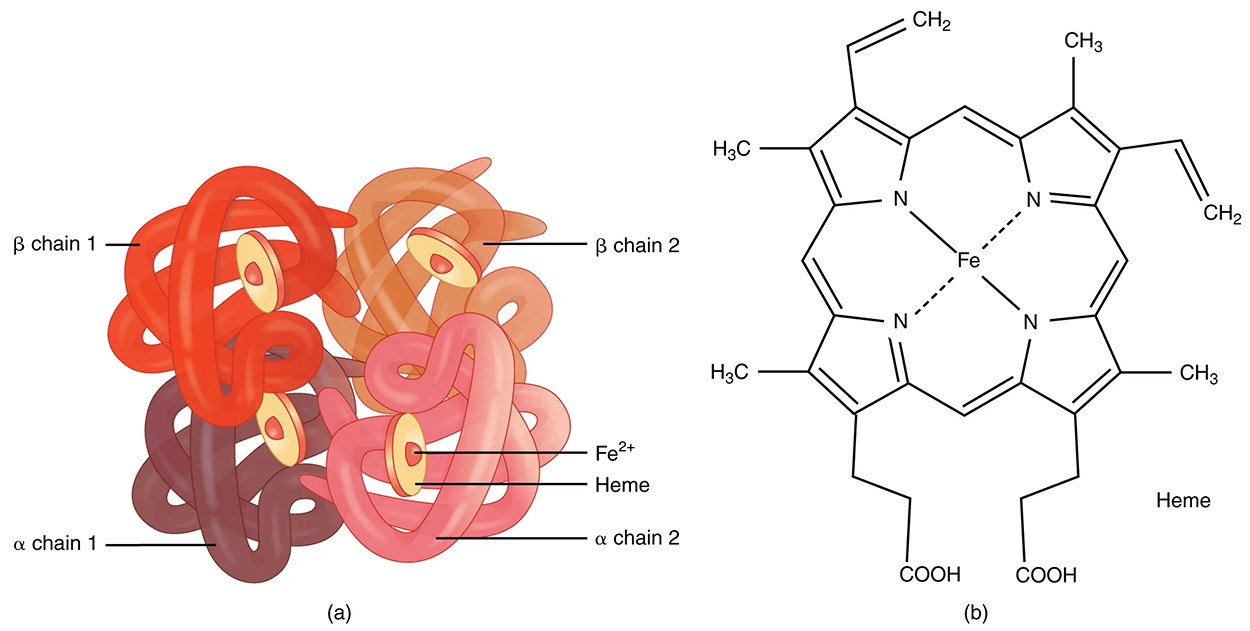

Hemoglobin is a large molecule made up of proteins and iron. It consists of four folded chains of a globin protein, designated alpha 1, alpha 2, beta 1, and beta 2 (see label a, below). Each of these globin molecules is bound to a red pigment molecule called heme, which contains an ion of iron (Fe²⁺) (see label b, below).

Each iron ion in the heme can bind to one oxygen molecule; therefore, each hemoglobin molecule can transport four oxygen molecules. An individual erythrocyte may contain about 300 million hemoglobin molecules and, therefore, can bind to and transport up to 1.2 billion oxygen molecules.

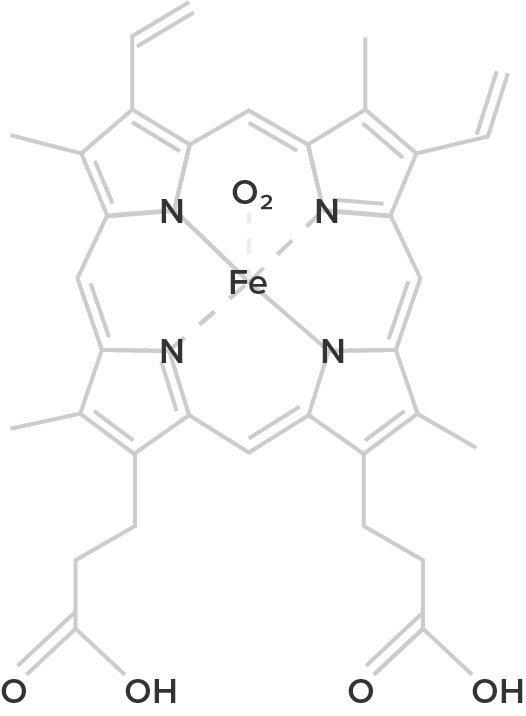

In the lungs, hemoglobin picks up oxygen, which binds to the iron ions, forming oxyhemoglobin. The bright red, oxygenated hemoglobin travels to the body tissues, where it releases some of the oxygen molecules, becoming darker red deoxyhemoglobin. Oxygen release depends on the need for oxygen in the surrounding tissues, so hemoglobin rarely, if ever, leaves all of its oxygen behind. In the capillaries, carbon dioxide (CO₂) enters the bloodstream. About 76% dissolves in the plasma, some remaining as dissolved CO₂, and the remainder forming bicarbonate ions. About 23–24% of it binds to the amino acids in hemoglobin, forming a molecule known as carbaminohemoglobin. From the capillaries, the hemoglobin carries CO₂ back to the lungs, where it releases it for the exchange of oxygen.

| Red | Blue | Green | Violet |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Humans and the majority of other vertebrates | Spiders, crustaceans, some mollusks, octopuses, and squids | Some segmented worms, some leeches, and some marine worms | Marine worms including peanut worms, penis worms, and brachiopods |

| Hemoglobin | Hemocyanin | Chlorocruorin | Hemerythrin |

|

|

|

|

|

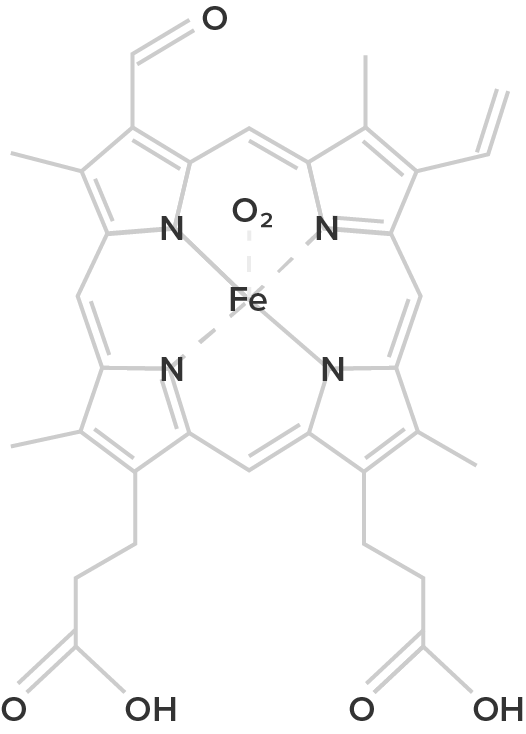

Heme B (oxygenated form) |

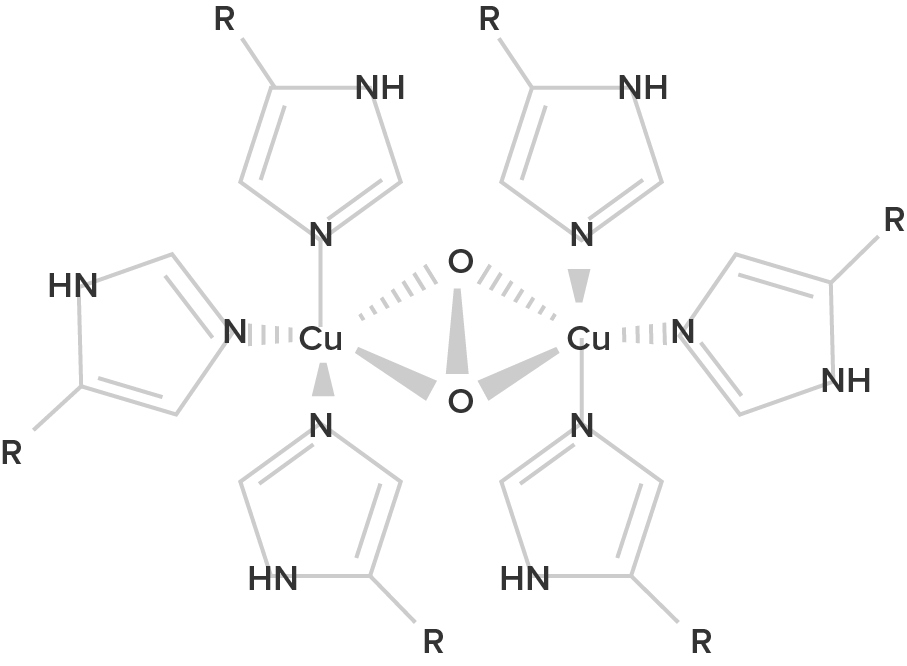

Hemocyanin B (oxygenated form; R = histidine residues) |

Chlorocruorin (oxygenated form) |

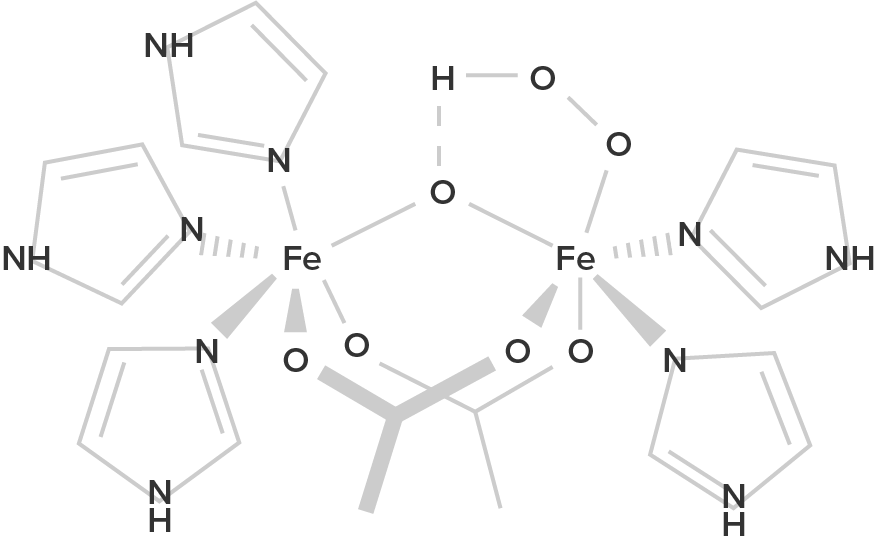

Hemerythrin (oxygenated form) |

| Hemoglobin is a protein found in the blood, built up from subunits containing "hemes". These hemes contain iron, and their structure gives blood its red color when oxygenated. Deoxygenated blood is a deep red color–not blue! | Unlike hemoglobin, which is bound to red blood cells, hemocyanin floats free in the blood. Hemocyanin contains copper instead of iron. When deoxygenated, the blood is colorless, but when oxygenated, it gives a blue coloration. | Chemically similar to hemoglobin; the blood of some species contains both hemoglobin and chlorocruorin. Light green when deoxygenated, it is green with oxygenated, although when more concentrated it appears light red. | Hemerythrin is only 1/4 as efficient at oxygen transport when compared to hemoglobin. In the deoxygenated state, hemerythrin is colorless, but it imparts a violet-pink color when oxygenated. |

Changes in the levels of RBCs can have significant effects on the body’s ability to effectively deliver oxygen to the tissues. This can occur for many reasons including reduced hematopoiesis, increased RBC damage or death, insufficient hemoglobin, and more. In determining the oxygenation of tissues, the value of the greatest interest in healthcare is the percent saturation; that is, the percentage of hemoglobin sites occupied by oxygen in a patient’s blood. Clinically this value is commonly referred to simply as “percent sat.”

Percent saturation is normally monitored using a device known as a pulse oximeter, which is applied to a thin part of the body, typically the tip of the patient’s finger. Normal pulse oximeter readings range from 95–100%. Lower percentages reflect hypoxemia, or low blood oxygen levels in the blood. The term hypoxia is more generic and simply refers to low oxygen levels in the body. Oxygen levels are also directly monitored from free oxygen in the plasma typically following an arterial stick. When this method is applied, the amount of oxygen present is expressed in terms of partial pressure of oxygen or simply P₀₂ or PO2 and is typically recorded in units of millimeters of mercury, mm Hg.

The kidneys filter about 180 liters (~380 pints) of blood in an average adult each day, or about 20% of the total resting volume, and thus serve as ideal sites for receptors that determine oxygen saturation. In response to hypoxemia, less oxygen will exit the vessels supplying the kidney, resulting in hypoxia (low oxygen concentration) in the tissue fluid of the kidney where oxygen concentration is actually monitored. Interstitial fibroblasts within the kidney secrete EPO, thereby increasing RBC production and restoring oxygen levels. In a classic negative-feedback loop, as oxygen saturation rises, erythropoietin (EPO) secretion falls, and vice versa, thereby maintaining homeostasis.

Populations dwelling at high elevations, with inherently lower levels of oxygen in the atmosphere, naturally maintain a hematocrit higher than people living at sea level. Consequently, people traveling to high elevations may experience symptoms of hypoxemia, such as fatigue, headache, and shortness of breath, for a few days after their arrival. In response to hypoxemia, the kidneys secrete EPO to step up the production of RBCs until homeostasis is achieved once again. To avoid the symptoms of hypoxemia, or altitude sickness, mountain climbers typically rest for several days to a week or more at a series of camps situated at increasing elevations to allow EPO levels and, consequently, RBC counts to rise. When climbing the tallest peaks, such as Mt. Everest and K2 in the Himalayas, many mountain climbers rely upon bottled oxygen as they near the summit.

| Term | Pronunciation | Audio File |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | he·mo·glo·bin |

|

| Heme | heme |

|

| Oxyhemoglobin | oxy·he·mo·glo·bin |

|

| Deoxyhemoglobin | de·oxy·he·mo·glo·bin |

|

| Carbaminohemoglobin | carb·ami·no·he·mo·glo·bin |

|

| Hypoxemia | hyp·ox·emia |

|

| Hypoxia | hyp·ox·ia |

|

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX "ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E" ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/DETAILS/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL