Table of Contents |

You have learned that in a perfectly competitive market, equilibrium prices are determined by demand and supply. Neither buyers nor sellers can influence the market outcome for price and quantity. Buyers and sellers of labor lack market power in perfectly competitive labor markets, because they represent a very small fraction of the market. Both buyers and sellers of labor accept the market-determined price of labor ( ) and quantity of labor (

) and quantity of labor ( ).

).

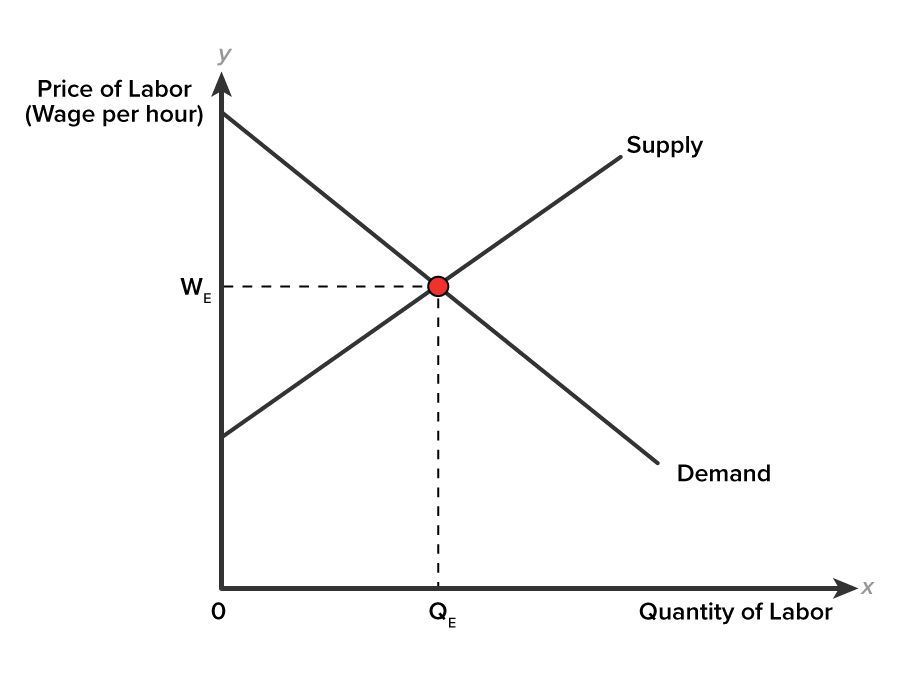

In equilibrium, the quantity of labor supplied and the quantity of labor demanded are equal at wage equilibrium. At wage equilibrium, employers find the number of workers they are seeking, and all individuals seeking employment find jobs. The graph below illustrates the case of wage determination in a perfectly competitive labor market.

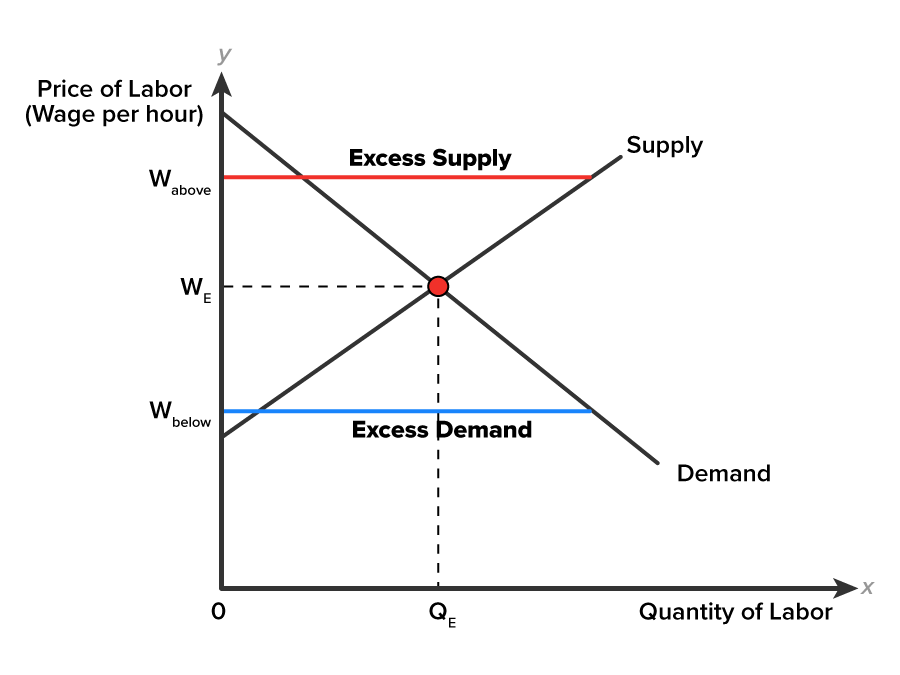

When the price of labor is not at equilibrium, economic forces work to return the market to equilibrium. Suppose the graph below represents the labor market for tutors in the local community. If the wage rate for tutors in the local community was above the market equilibrium ( ), it would attract more individuals to tutoring work than employers would want to hire at equilibrium quantity (

), it would attract more individuals to tutoring work than employers would want to hire at equilibrium quantity ( ).

).

At an above-equilibrium wage rate, excess supply, or a surplus of workers occurs. In a situation of excess supply in the labor market, with many applicants for every job opening, employers will have an incentive to offer lower wages. The wage rate for tutors will move back down toward equilibrium, and the market will clear once again.

Alternatively, if the wage rate is below the equilibrium ( ), then a situation of excess demand, or a shortage of workers arises. In this case, employers encouraged by the below-equilibrium wage rate want to hire more tutors than are available at

), then a situation of excess demand, or a shortage of workers arises. In this case, employers encouraged by the below-equilibrium wage rate want to hire more tutors than are available at  . Some individuals will desire to work at this below-equilibrium wage rate. Notice that

. Some individuals will desire to work at this below-equilibrium wage rate. Notice that  intersects the supply curve at its lower end.

intersects the supply curve at its lower end.

In response to a shortage of tutors, some employers will begin to offer higher pay to attract tutors. Other employers will have to match the higher pay to keep their own employees. A change in the price of labor (wage per hour) will result in a change in the quantity supplied of labor. A higher wage will encourage more individuals to enter the market for tutors. Similarly, a lower wage will cause individuals to leave the market for tutors. As quantity adjusts to the price change, the market will move toward equilibrium, and once again clear. When surplus and shortage situations occur in a labor market, it is the free movement of the price that causes the market to adjust back toward equilibrium.

If wages are determined by the interaction of supply and demand, then changes in supply and demand should cause wages to change. Changes to labor supply or labor demand are a result of changes in non-wage factors, assuming the price of labor (wage per hour) is held constant (ceteris paribus).

You have learned how a change in one non-wage factor shifts the labor supply and demand curve. Now, let’s turn our attention to the graphical analysis of wage determination. We will examine the cases of partial change when only one curve shifts, and then the case of simultaneous changes when both curves shift in the labor market.

Now let’s explore four scenarios of partial changes in supply or demand (ceteris paribus).

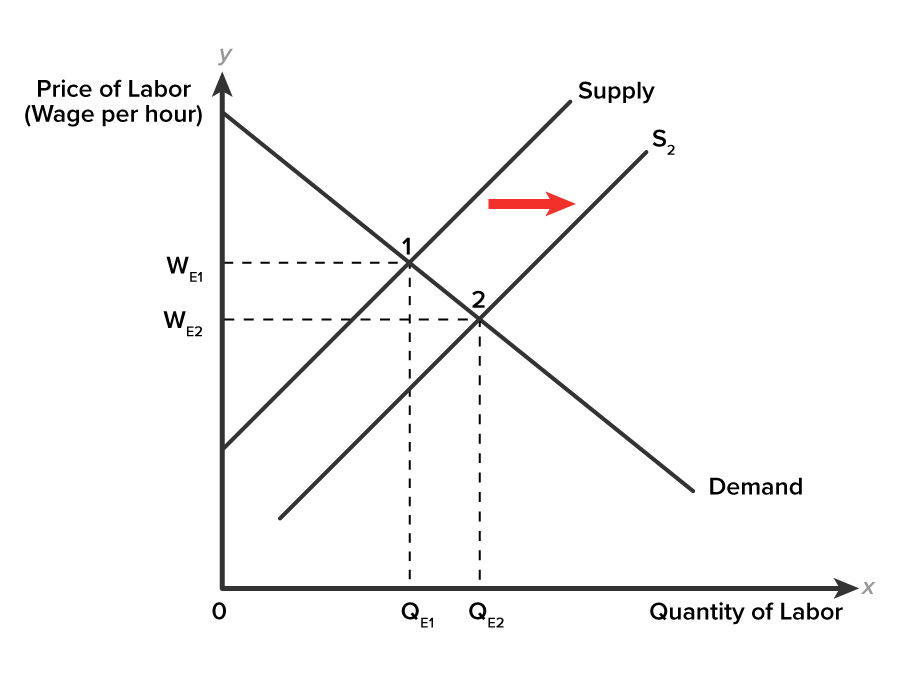

Suppose that an individual could attend a two-year college paying for books, but not tuition or room and board. More individuals would obtain a two-year degree, increasing human capital. Lowering the cost of acquiring the requisite human capital would result in a higher supply of workers with degrees. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that workers with an associate’s degree had median weekly earnings of $938 in 2020, compared with $781 for workers with a high school diploma. If more individuals with degrees are seeking employment, what will the effect be on wages in this market?

Assuming all else is the same (ceteris paribus), an increase in supply causes a rightward shift of the supply curve along the demand curve. At the new equilibrium (2) wage falls from  to

to  , and the quantity of labor rises from

, and the quantity of labor rises from  to

to  . Wage is now lower with more workers in the market.

. Wage is now lower with more workers in the market.

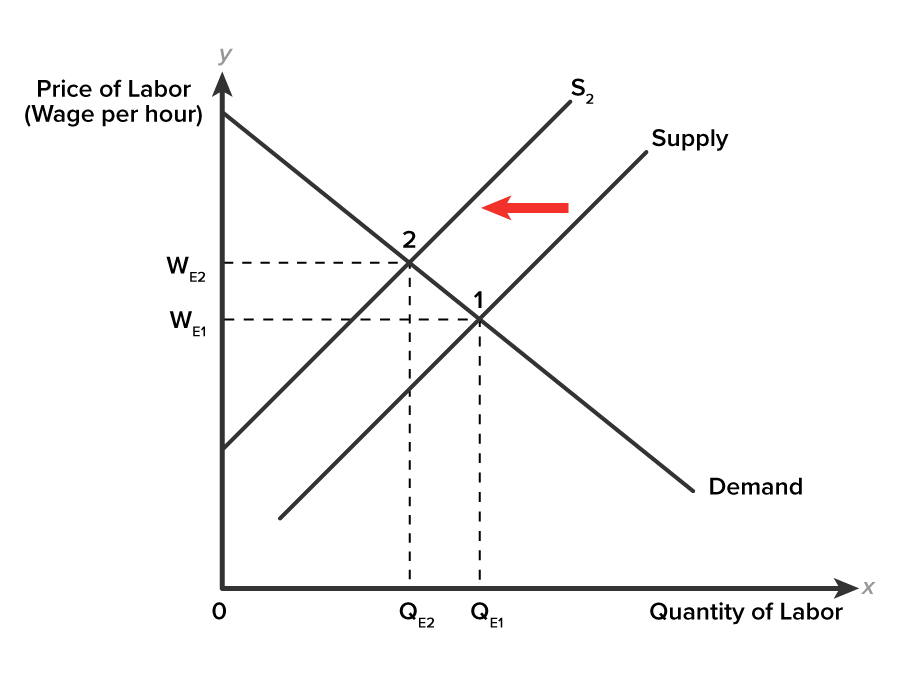

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, bank teller is among one of the fastest declining occupations in the U.S. In 2020, the median salary of a bank teller was about $32,000. As new technology integrates into the banking industry, the employment opportunities for tellers has declined. Between 2020 and 2030, employment is projected to fall by 73%. Fortunately the individual skills learned as bank teller easily transfer to customer service representative. How will this transition of alternative job type affect wage in the market for bank tellers?

Assuming all else is the same (ceteris paribus), a decrease in supply causes a leftward shift of the supply curve up along the demand curve. At the new equilibrium (2) wage rises from  to

to  , and the quantity of labor falls from

, and the quantity of labor falls from  to

to  . Wage is now higher with fewer workers in the market.

. Wage is now higher with fewer workers in the market.

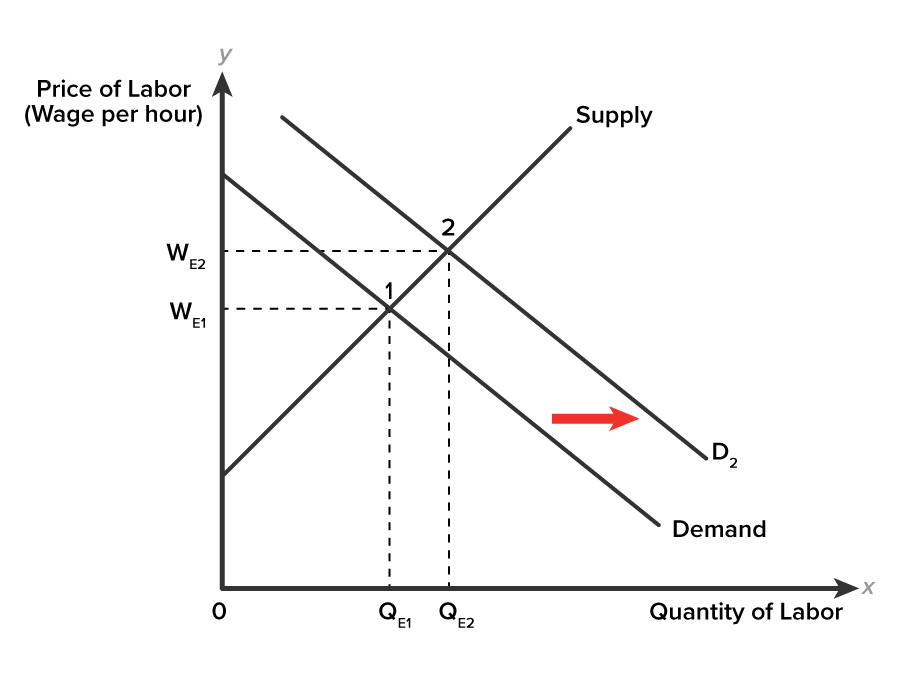

Suppose that firms invest more in the physical capital used by assembly-line workers in the auto industry. Such an investment increases worker productivity, and this reduces the cost of production. As marginal productivity of labor rises, firms will hire more workers. How does this affect the market wage for assembly-line workers?

Assuming all else is the same (ceteris paribus), an increase in demand causes a rightward shift of the demand curve up along the supply curve. At the new equilibrium (2) wage rises from  to

to  , and the quantity of labor rises from

, and the quantity of labor rises from  to

to  . Wage and the quantity of workers are both higher.

. Wage and the quantity of workers are both higher.

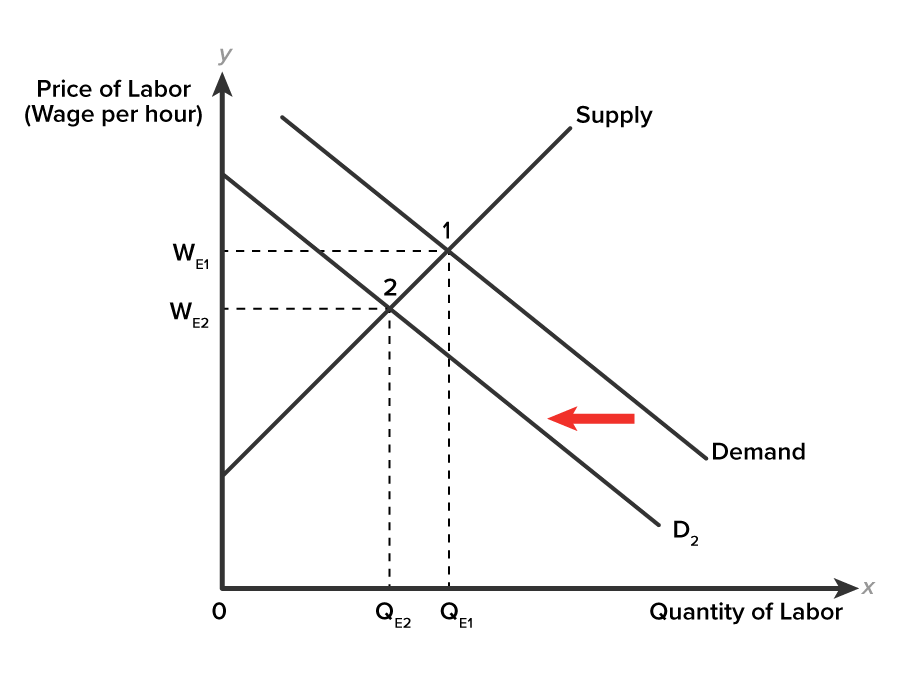

Suppose that concern over air quality causes the government to impose strict new laws on the grade of coal that can be mined. What is the likely impact on the market for coal miners as the number of coal mining operations shrink?

Assuming all else is the same (ceteris paribus), a decrease in demand causes a leftward shift of the demand curve down along the supply curve. At the new equilibrium (2) wage falls from  to

to  , and the quantity of labor falls from

, and the quantity of labor falls from  to

to  . Wage and the number of workers are now both lower.

. Wage and the number of workers are now both lower.

Let’s now consider one scenario of simultaneous change in supply or demand (ceteris paribus):

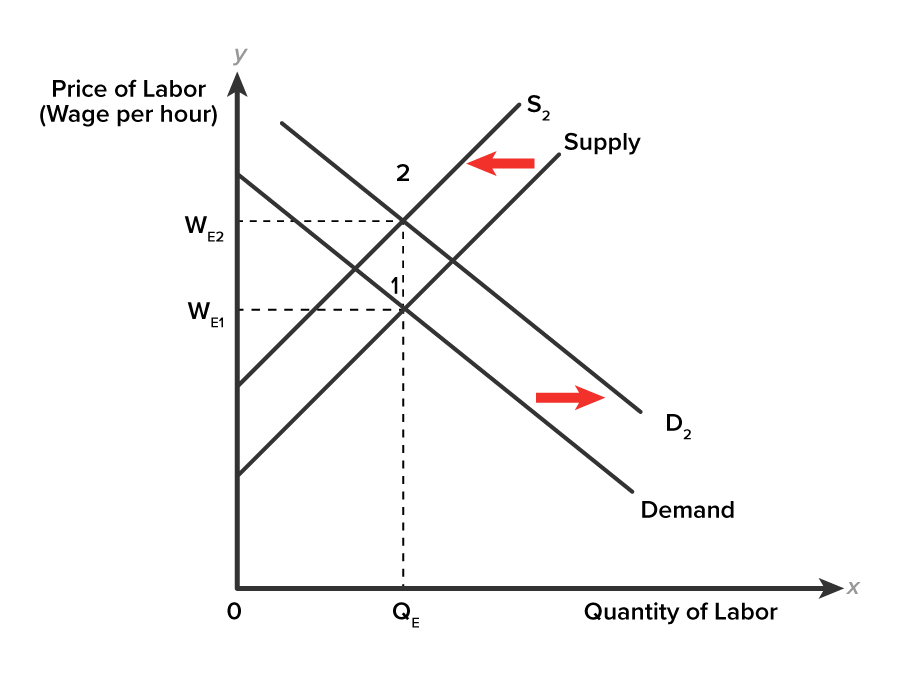

Suppose that the labor market experiences changes in both supply and demand simultaneously. What will the effect be on wages in the labor market? Let’s consider two events, ceteris paribus.

Event 1: A pandemic causes parents to choose caregiving over paid employment. This event affects suppliers of labor, in particular, parents with children. If parents choose to withdraw from their jobs, then the supply of labor will decrease, and the supply curve will shift to the left.

Event 2: A surge in demand for goods and services for computer tablets and learning apps raises the price of those goods and service. The higher price will incentivize profit-maximizing firms to produce more products, which will require more workers. The demand for labor will increase, and the demand curve will shift to the right.

Assuming all else is the same (ceteris paribus), an increase in demand for labor causes a rightward shift of the demand curve up along the supply curve, while the decrease in the supply of labor causes a leftward shift of the supply curve up along the demand curve.

At the new equilibrium (2) wage rises from  to

to  , and the quantity of labor appears to not have changed from

, and the quantity of labor appears to not have changed from  . It is clear that wages rose. What is not clear is what happened to quantity—in this situation, we say that quantity is indeterminate. It cannot be accurately determined, because the magnitude of the line shifts could result in different quantity outcomes. Shifting the demand curve further to the right would appear to result in a higher quantity. Shifting the supply curve further to the left would appear to result in a lower quantity of labor.

. It is clear that wages rose. What is not clear is what happened to quantity—in this situation, we say that quantity is indeterminate. It cannot be accurately determined, because the magnitude of the line shifts could result in different quantity outcomes. Shifting the demand curve further to the right would appear to result in a higher quantity. Shifting the supply curve further to the left would appear to result in a lower quantity of labor.

Complete the following Try It activity to explore one more simultaneous change situation:

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-2e/pages/1-introduction. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Torpey, E. (n.d.). Career Outlook: Education Pays, 2020. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved September 6, 2022, from

www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2021/data-on-display/education-pays.htm

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, April 19). Employment Projections: Fastest Declining Occupations. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved September 6, 2022, from www.bls.gov/emp/tables/fastest-declining-occupations.htm#1