Table of Contents |

Similar to their Spanish and French Catholic rivals, English Puritans used the conversion of native peoples as one way to justify their presence in North America. Unlike the Spanish or French, however, Puritans sought to convert native peoples to their particular version of Protestant Christianity.

John Eliot, the leading Puritan missionary in New England, urged Indigenous People in Massachusetts to live in “praying towns” established by English authorities for converted Native Americans and to adopt the Puritan emphasis on the centrality of the Bible. In keeping with the Protestant emphasis on reading scripture, he translated the Bible into the local Algonquian language and published his work in 1663. Eliot hoped that, as a result of his efforts, some of New England’s native inhabitants would become preachers.

Yet, relationships between Puritan settlers and Native American tribes deteriorated as Puritans expanded their towns aggressively and as European livestock and land use methods increasingly disrupted native life. Colonists cleared land for agriculture and, most importantly, constructed fences to designate private property ownership. They also let livestock, such as cattle and hogs, roam free for all or part of the year, and these animals wreaked havoc on native villages and agricultural plots, which were unfenced and often changed from year to year. A herd of cattle could trample a field of corn, beans, and squash in a matter of hours. There were also numerous cases of native women and children arriving at a place to gather nuts or berries, only to discover that a colonist’s hogs had beaten them to it. John Winthrop assured potential colonists that they could utilize New England’s natural resources for their benefit. Colonists and Winthrop alike neglected the fact that Native Americans claimed much of the same land and resources.

When the Puritans began to arrive in the 1620s and 1630s, local Algonquians viewed them as potential allies in the conflicts already simmering between rival native groups. Colonists exploited these rivalries to serve their own ends. In addition, colonial ideas about land use and settlement, along with efforts to convert the native people to Protestantism, contributed to a series of violent confrontations between the Northern Colonists and the Native American peoples of the region.

In 1637, an English fur trader was killed by members of the Pequot tribe, who controlled much of southern New England and exacted tribute from other Native American tribes, including the Narragansett and Mohegan. Outraged by the incident, Puritans in Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth allied themselves with the Narragansett and Mohegan people against the Pequot, and the Pequot War began.

The war ended in disaster for the Pequots. In May 1637, the Puritans attacked a large group of several hundred Pequot people along the Mystic River in Connecticut. To the horror of their native allies, the Puritans massacred all but a handful of the men, women, and children they found. By the time the war ended, most of the Pequot people had been killed or sold into slavery, and their lands in southern New England were claimed by colonists.

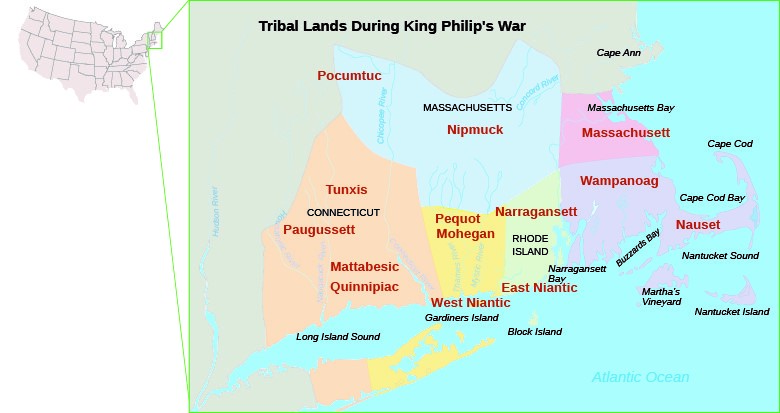

By the late 17th century, the Puritans had pushed their way further into the interior of New England, establishing outposts along the Connecticut River Valley. Such expansion, along with continued tensions with nearby tribes, contributed to the outbreak of King Philip’s War by 1675, the bloodiest conflict in the history of colonial New England.

The Wampanoag leader, Metacom (also known as King Philip among the English), was determined to stop the encroachment. The Wampanoag people, along with the Nipmuck, Pocumtuck, and Narragansett people, took up the hatchet to drive the English from the land. In the ensuing conflict, native forces succeeded in attacking half of the towns in Puritan New England, destroying 12 towns and killing approximately 1,000 colonists.

However, by the summer of 1676, English Puritans, aided by Mohegans as well as by individuals from various “praying towns,” turned the tide. Metacom was captured and killed. A number of Native American villages were destroyed, and many Native American men, women, and children were killed or sold into slavery.

Conflict with the Pequot people and with Metacom forever changed the English perception of native peoples. Englishmen defined their freedom by their ability to acquire land, even if it came by force. Such freedom rested on the dispossession of the region’s native inhabitants, and Puritan writers took great pains to vilify Native Americans as bloodthirsty savages. Hatred became a defining feature of Native American–English relationships in the Northeast. Native Americans were no longer the subjects of conversion. Rather, they became obstacles to colonial progress.

When settling in New England, Puritans discovered a variety of different tribes (most ravaged by European diseases) and were able to create alliances with certain groups to exploit potential rivalries. The exact opposite occurred for the first colonists of Virginia and Chesapeake.

By choosing to settle along the rivers on the banks of Chesapeake, the English unknowingly placed themselves at the center of the Powhatan Empire, a powerful Algonquian confederacy of 30 native groups with perhaps as many as 22,000 people. The territory of the equally impressive Susquehannock people also bordered English settlements at the north end of Chesapeake Bay.

Tensions between the English at Jamestown and the Powhatan people contributed to the colony’s early struggles. The First Anglo-Powhatan War (1609–1614) resulted not only from the English colonists’ intrusion into Powhatan land but also from their refusal to follow the native protocol of giving gifts. English actions, particularly the indiscriminate killing of Native Americans and the destruction of Native American crops infuriated and insulted the Powhatan people. In 1613, colonists captured Pocahontas (also called Matoaka), the daughter of a Powhatan headman named Wahunsonacook, and gave her in marriage to Englishman John Rolfe. Their union, and her choice to remain with the English, helped quell the war in 1614.

Peace in Virginia did not last long, however. The Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1620s) broke out because of the expansion of the English settlement nearly 100 miles into the interior. In 1622, the Powhatan, now led by Opechancanough, led a surprise attack that killed almost 350 English people, about a third of the English settlers in Virginia. The English responded by dividing themselves into military bands and annihilating every Powhatan village around Jamestown. Indeed, the Virginia Company insisted on the extermination of the native population in order “to gain free range of the country.”

English supremacy was reinforced during the Third Anglo-Powhatan War (1644–1646), which began with a surprise attack in which the Powhatan people (still led by Opechancanough, who was presumably 100 years old by this point) killed around 500 English colonists. However, the English response was swift and harsh. Upon the end of the conflict, the English forced the Powhatan into a treaty that recognized Jamestown’s supremacy and acknowledged King Charles I as their sovereign. The remaining Powhatan people were also forced westward and were required to ask permission before entering areas of English settlement.

The Anglo-Powhatan Wars, which spanned nearly 40 years, illustrate the degree of native resistance that resulted from English intrusion into the Powhatan Confederacy. After a short initial period of peace, the English and Powhatan coexisted in a state of tension and warfare for a significant period. Similar to what later occurred in the Northern Colonies, however, English colonists in Chesapeake ultimately saw the Powhatan as an obstacle to an expanding colonial economy; one that, in this case, revolved around tobacco.

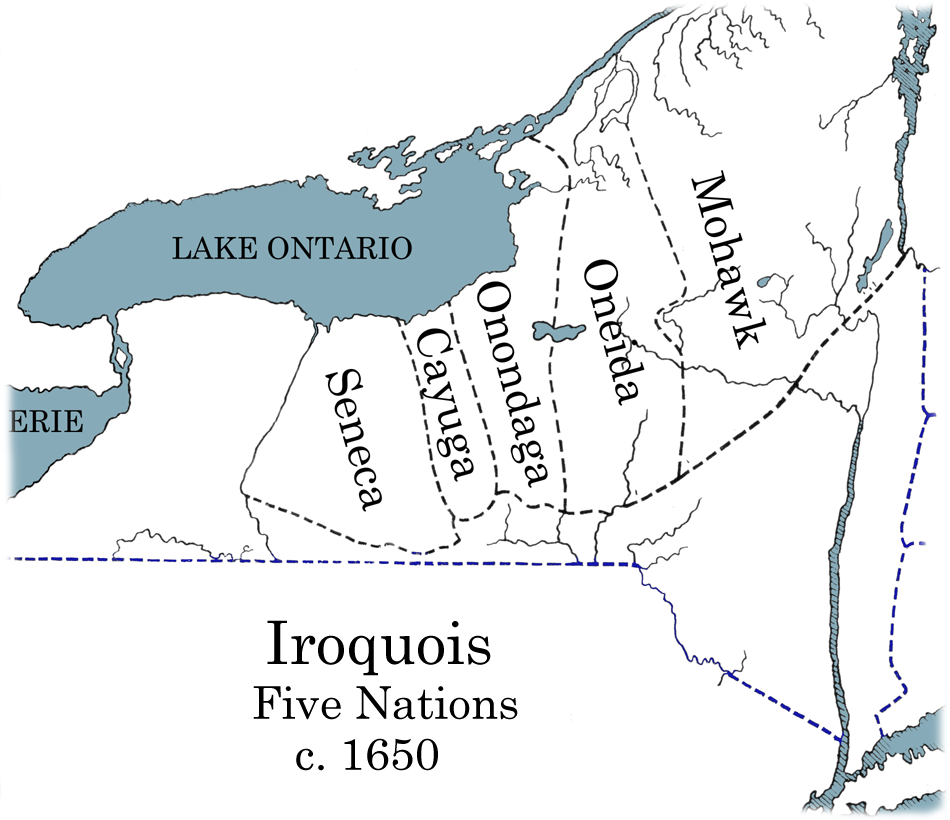

In contrast to Metacom in the Northern Colonies or the Powhatan people in the Southern Colonies, the Iroquois Confederacy in the Middle colonies—specifically New York and the Great Lakes region—offers an example of how native peoples could influence imperial politics to their advantage. Indeed, the Five Nations of the Iroquois, which comprised the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, represented a significant political and economic center of Native American power for much of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Most importantly, the Iroquois Confederacy successfully pursued a policy of continuous negotiation and conflict with both English colonists and, to the north, the French in Canada. For instance, for much of the 17th century, the Iroquois Confederacy was at war with the French and their Native American allies, particularly the Algonquian.

Beginning in 1609, the Iroquois nations began to take back prime beaver-trapping land from the French, including land that belonged to the Huron and Erie tribes. These Beaver Wars extended for several decades afterward. After several successful battles, the Iroquois began incorporating more hunting grounds and more tribes into the Confederacy. These efforts would expand well throughout the Great Lakes region, with the influence of the Iroquois Confederacy reaching all the way to modern-day Chicago. At times, these battles would spill into New York’s (and Virginia’s) colonial territory, and the English colonists would fight to maintain their claim to the land, but the vast majority of the events occurred outside of the English holdings.

By 1701, fighting between the Iroquois people and France’s Native American allies came to a halt, and peace generally characterized French and Native American relations along with English and Native American relations throughout the first half of the 1700s. During this period, the Iroquois continued to live in their own villages under their own government while enjoying the benefits of trade with both the French and the English. Trade and diplomacy with the French typically occurred in Quebec or Montreal. Meanwhile, Albany became a prominent center for trade and diplomacy between the Iroquois people and the English.

The survival and even the expansion of the Iroquois Confederacy was in part a product of the tribes’ location in an important middle ground between the French and English colonial empires. It was also a result of the role that the Iroquois could play in acquiring furs, which remained a valuable commodity in the Atlantic World. The influence of the Iroquois over neighboring tribes, combined with its location in the Middle Colonies, allowed the Confederacy to play a significant mediating role in imperial politics during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL