Table of Contents |

Creating wealth for Britain remained the king's primary goal for his North American colonies. During the second half of the 17th century, Great Britain gained better control of trade with its American colonies through a series of measures known as the Navigation Acts.

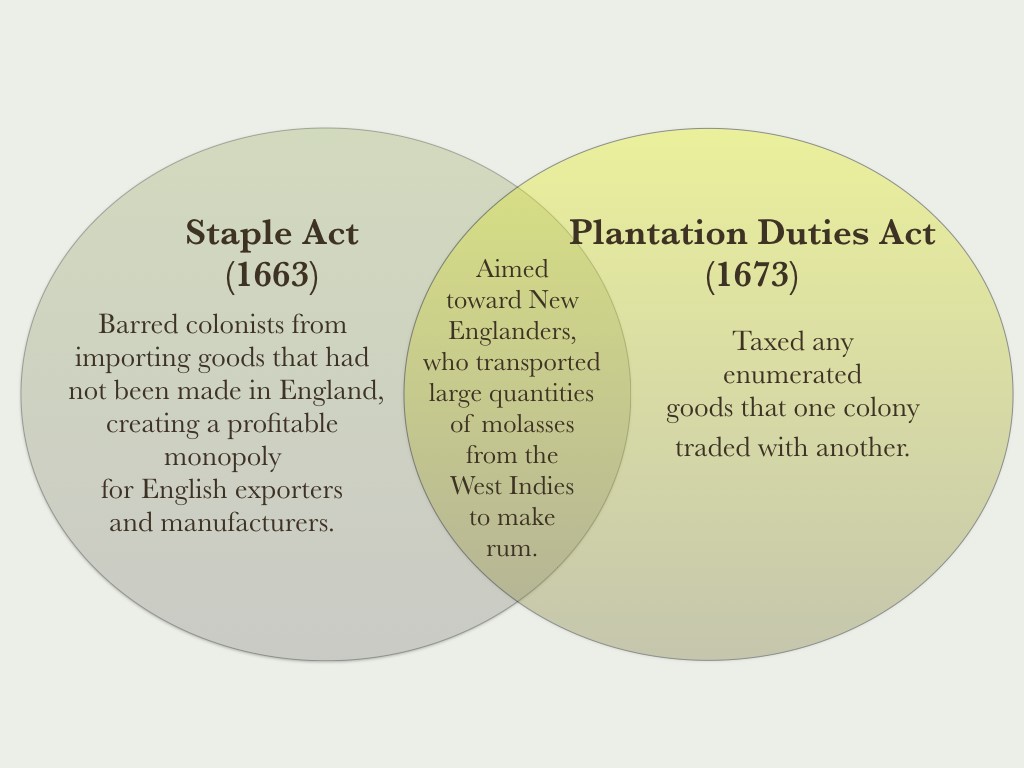

In 1651, two years after the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell initiated the process of economic centralization by enacting a Navigation Ordinance. This ordinance required that only English ships could carry goods between England and the colonies. The captain and three fourths of the crew had to be English. Most importantly, the ordinance listed a series of enumerated goods: commodities produced in the colonies that could only be transported to ports controlled by England. Among the most valued of these goods were tobacco, sugar, cotton, and indigo (a blue dye valuable for textile production). The ordinance granted English merchants a monopoly in the import of those goods from the colonies and in their eventual export to other nations.

Charles II organized the Board of Trade to oversee the implementation of the Navigation Acts. First established in 1675, the Board of Trade was an administrative body intended to create stronger regulatory ties between the colonial governments in North America and the English Crown.

The duties of the Board included:

Together, the Navigation Acts created an imperial economic system in which American colonial production flowed through English channels. This system created important benefits for the colonies. Colonial producers and merchants often enjoyed stable prices for their goods. Producers and merchants enjoyed the protection of the English Navy when shipping their goods across the Atlantic Ocean. Finally, these same producers and merchants were treated as English citizens when conducting commerce in the Atlantic World, which further tied them to England.

American colonists discovered that English laws affected more and more of their daily business, as they conducted commerce and purchased goods within the Atlantic World under the Navigation Acts. For example, colonial merchants had to establish relationships with English customs officials. Major colonial ports, such as Boston and Philadelphia, soon featured a variety of imperial officials who administered colonial affairs.

Charles II died in 1685. James II (the former Duke of York who oversaw the Royal African Company) ascended the throne and attempted to gain greater influence over colonial politics with limited success.

In 1686, James II set out to centralize the administration of the Northern colonies by creating an enormous new colony called the Dominion of New England. The Dominion included all of the New England colonies (Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Plymouth, Connecticut, New Haven, and Rhode Island). In 1688, the Dominion was enlarged by the addition of New York and New Jersey. James II placed Sir Edmund Andros, a former colonial governor of New York, in charge.

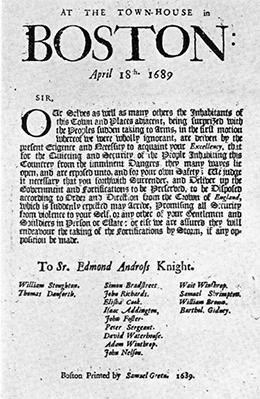

Andros was loyal to James II and his family. He had little sympathy for English colonists and was not required to listen to any of the colonial assemblies. Andros appointed his own officials in place of elected ones, imposed taxes without approval from colonial representatives, and called into question many colonial land grants that did not acknowledge the king or himself. Perhaps most importantly, he was committed to enforcing the Navigation Acts, which many colonists had ignored. This enforcement threatened to disrupt colonial merchants whose businesses relied on smuggling.

Concerns about the authoritarian nature of the king's efforts to centralize colonial administration were part of the growing concern about the English monarchy. James II attempted to model his rule on the reign of his cousin, King Louis XIV of France. This meant centralizing political strength around the throne to give the monarchy absolute power. James II also worked to modernize the army and the navy, and he maintained a standing army in times of peace. This greatly alarmed the English people, who believed that such a force would be used to crush their liberty.

James II practiced a strict and intolerant form of Roman Catholicism, like his cousin Louis XIV. He had a Catholic wife, and when they had a son, the potential for a Catholic heir to the English throne became a threat to English Protestants. As James’s strength grew, his opponents feared he would turn England into a Catholic monarchy with absolute power over the English people.

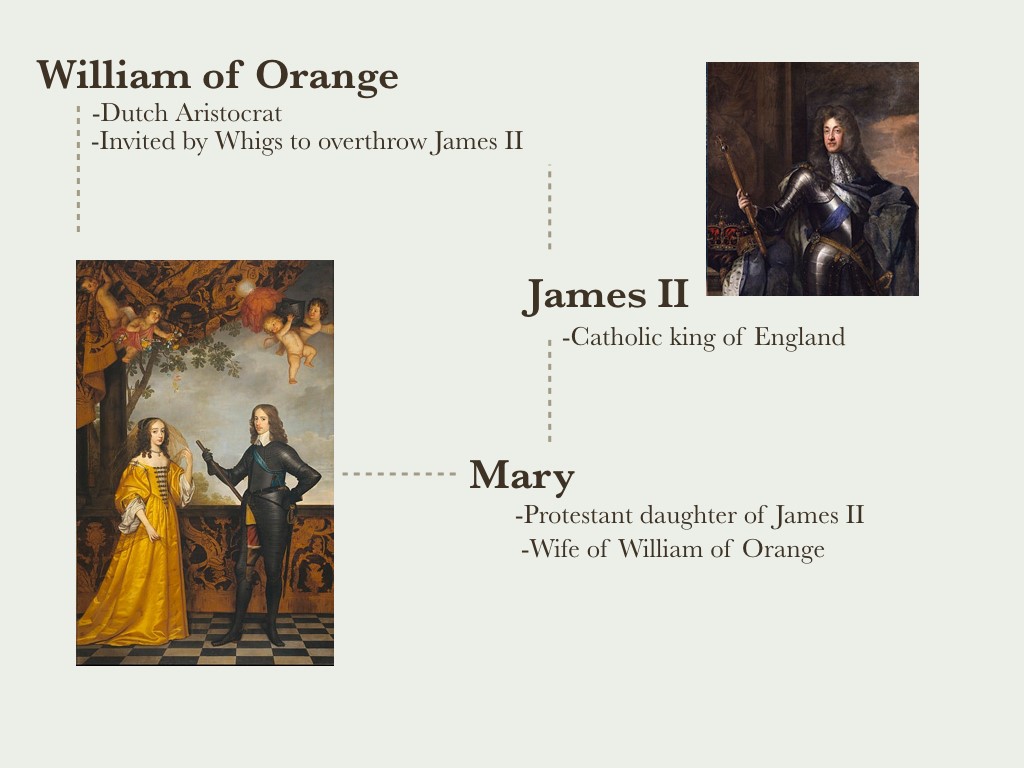

In England, opponents of James II’s efforts to create a centralized Catholic state were known as Whigs. They included a number of English aristocrats and leaders of the Anglican Church, who insisted upon the supremacy of Parliament in national affairs. Parliament, the legislative body of England’s government, is comprised of the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The Whigs invited a Dutch aristocrat, William of Orange (who was the husband of James II’s Protestant daughter Mary), to assume the English throne on their behalf and overthrow James II. See the image below.

William arrived in England in November 1688 with an army of over 21,000 men, the majority of whom were Dutch. English aristocrats and the Anglican Church rallied to his cause, and James II was forced to flee to France. The Glorious Revolution was completed when William of Orange (now William III) and his wife Mary became monarchs in 1689. The Glorious Revolution might be better understood as a coup that was spearheaded by English Protestant aristocrats.

News that James II had been overthrown soon reached the colonies. After hearing the news in 1689, Bostonians overthrew the government of the Dominion of New England. In the process, they jailed Sir Edmund Andros and other leaders of the regime. The removal of Andros from power illustrated New England’s animosity toward Andros’s disregard for the colonial assemblies and his vigorous enforcement of the Navigation Acts.

The Glorious Revolution showed how colonial politics mirrored those in England. The Revolution also provided a shared experience for Englishmen and colonists alike. Subsequent generations would refer to the events of 1688 and 1689 as a heroic defense of English liberty against would-be tyrants.

The Glorious Revolution led to the establishment of an English nation that limited the power of the king and provided protections for English citizens. English colonists in North America assumed that such protections extended to them. For a time at least, this appeared to be the case.

In October 1689, the same year that William and Mary took the throne, Parliament issued a Bill of Rights that established a constitutional monarchy in England. It stipulated Parliament’s independence from the monarchy by listing certain sole parliamentary powers such as control over taxation. It also established certain individual rights for English citizens, most notably trial by jury and habeas corpus (the requirement that authorities bring an imprisoned person before a court to demonstrate the cause of the imprisonment).

Parliament also issued a Toleration Act, which allowed for greater religious diversity throughout the Empire, including North America. The Church of England (Anglican Church) remained the official state religious establishment, but the Toleration Act extended more freedom to Protestant denominations that did not conform to its views. Thus, by the end of the 17th century, all of England's North American colonies (including Massachusetts Bay) were required to tolerate all Protestant denominations. Several colonies, including Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Delaware, and New Jersey, took such toleration a step further and refused to recognize an official religious establishment.

Imperial administration also espoused an element of toleration in matters of commerce. During the administration of Prime Minister Robert Walpole (1721–1742), England exercised lax control over colonial trade despite the Navigation Acts. Historians have described this lack of strict enforcement of the Navigation Acts as salutary neglect. The Navigation Acts remained law, but customs officials did not aggressively prosecute smuggling in the colonies. In addition, nothing prevented colonists from building their own fleet of ships to engage in such trade.

Salutary neglect extended to colonial governance as well. The administration of colonial North America in the wake of the Glorious Revolution created a two-tiered system, one in which certain aspects of colonial governance were perceived as separate from imperial administration.

Each colony had a governor appointed by the Crown. These governors usually had authority over the military. The Crown also retained the authority to veto colonial legislation, but many governors paid little attention to colonial affairs. Thus, colonial assemblies exerted greater control in local politics, specifically over matters of government expenditures and taxation. For instance, colonial assemblies often agreed to pay the salary of a royal governor or his administrators in exchange for concessions on government appointments and other issues. Some colonies also printed paper money despite opposition from royal governors.

By the 18th century, the ability to vote in the colonies was determined by property qualifications rather than by church membership. This expanded basic political participation in colonial affairs among landholders and property owners. Colonists who owned property could secure a voice in the colonial assemblies, which retained control over everyday lawmaking within the colonies. Such work contributed to a perception that colonial governance was separate from imperial administration. It also enabled leaders of colonial assemblies to act as political leaders for the colonies.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL