Table of Contents |

Several events that devastated the economy and labor relations led many Americans to refer to the 1890s as the “Terrible Nineties.” The first of these was the Panic of 1893, which started the worst financial crisis and economic depression in the United States until the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The Panic was the result of two major causes. The first was continued speculation in railroads. Throughout the late 19th century, banks and investors fed the growth of the railroads with ever-increasing investment in industry and related businesses. This created a false impression of economic growth and contributed to the formation of a “bubble.” By the early 1890s, several railroads were at risk of failing due to expenses that outpaced returns on their construction, and from the related businesses that supported them. When the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Company closed in 1893, panicked investors cashed in bonds issued by other railroads, leading several of them to cease operations.

Many of the investors who pulled out of their railroad investments wanted to be sure that the bonds and securities they held were backed by gold. This created the second major cause of the Panic: a decrease in American gold reserves. Many investors, as well as middle-class Americans and politicians, blamed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 for this situation.

The act, which was passed partly in response to farmers’ demands for debt relief, attempted to raise the prices that farmers received for their goods by injecting more money into the economy. Doing so would help farmers to pay their debts. However, many investors and other businessmen believed that currency backed by silver was worth less than money backed by gold. They exchanged bank notes backed by silver for notes backed by gold, and severely depleted the nation’s gold reserves in the process.

In late June of 1893, the stock market crashed. President Grover Cleveland called Congress into session to resolve the crisis. Congress repealed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, but the collapse of railroad companies and the effects of a constrained money supply continued to ripple through the economy. As railroad companies closed or reduced operations and businessmen curtailed their investments, related industries and businesses closed or restricted activity, leading to massive layoffs.

Historians estimate that over three million Americans were unemployed in 1895. City residents grew accustomed to seeing homeless people on the streets and lining up at soup kitchens.

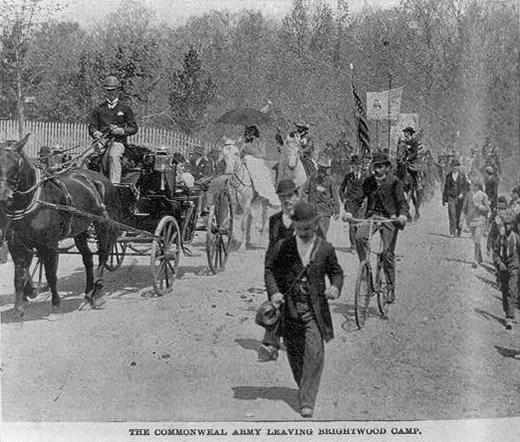

Americans organized to seek relief from their representatives during the economic downturn. Among the most notable of these efforts was Coxey’s Army.

In the spring of 1894, Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey began a march of unemployed laborers from Massillon, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. They planned to protest the repeal of the Silver Purchase Act, and demand that Congress pass a public works program that would put unemployed Americans back to work. As more people—several hundred in all—joined Coxey’s group, it became known as Coxey’s Army.

Following their arrival in Washington, Congress and President Cleveland ignored the Army’s demands for federal relief. Coxey and several other organizers were arrested for trespass after they walked on the grass outside the U.S. Capitol.

The story of Coxey’s Army shows that, in times of need, Americans were beginning to turn to the federal government for assistance. It also shows that the government, which was primarily interested in protecting business and patronage at this time, did not respond sympathetically.

The labor conflicts of the early 1890s revealed that industrialists were unwilling to negotiate with workers’ organizations and, when necessary, would call on the federal government to protect their interests.

The Homestead strike of 1892 pitted the nation’s largest steel producer—the Carnegie Steel Company—against the nation’s largest trade union—the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers—which was affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

The Homestead Steel Works, southeast of Pittsburgh, was part of the Carnegie Steel Company. Union members who worked there enjoyed relatively good relations with management until Henry C. Frick became the factory manager in 1889. When the union’s contract with Carnegie Steel came up for renewal in 1892, Andrew Carnegie was in Scotland and delegated Frick—who was known for his anti-union views—to negotiate with the union. When no settlement was reached by June 29th, Frick ordered a lockout of union workers. A barbed wire fence was erected around the facility, and 300 private security officers were hired to protect the new, nonunion laborers who were employed to replace the strikers.

On July 6, 1892, as the Pinkertons attempted to cross the river from Pittsburgh to the Homestead Mills, union workers engaged them in a gunfight that resulted in the deaths of several Pinkertons and strikers. The Pennsylvania Governor sent 8,000 militiamen to restore order and protect the nonunion workers.

Frick’s lockout of union steelworkers lasted until November. He survived a failed assassination attempt on his life by the anarchist Alexander Berkman. The strike ended with the defeat of the union: workers were individually required to ask Frick and his associates for permission to return to work.

The Pullman Strike, which occurred 2 years later, following the Coxey’s Army march in the summer of 1894, was another disaster for unionized labor during the 1890s.

The crisis began in the company town of Pullman, Illinois, where George Pullman’s Palace Car Company manufactured luxurious “sleeper” railroad cars. As the Panic of 1893 spread, and following the failure of several Northeastern railroad companies, Pullman fired half of his 6,000 employees and cut the remaining workers’ wages by an average of 25%. Pullman continued to charge high rents and prices in the company homes and stores where workers were required to live and shop.

The strike began on May 11, 1894, when Eugene V. Debs, President of the American Railway Union, ordered union rail workers throughout the country to stop handling trains that included Pullman sleeper cars. Almost all of America’s trains fell into this category, so the strike stopped railroad traffic across the nation.

Railroad managers called for federal assistance. In a solution designed by President Cleveland and his Attorney General to justify federal action, the government attached postal cars to trains. When Debs and the American Railway Union refused to obey an injunction that prohibited their interference in the delivery of the mail, Cleveland sent federal troops to run the trains—to ensure that the mail was delivered.

With troops handling the trains, the Pullman strike ended in July. Debs was arrested and sentenced to 6 months in prison for disobeying the court injunction. The American Railway Union was destroyed, leaving workers with no gains and less power than before.

Amidst the persistent labor conflict of the 1890s, Populist Party leaders displayed their sympathy with organized labor to gain union support in upcoming elections.

During the Homestead Strike of 1892, Kansas Populist organizer Mary Lease wrote the following editorial in the Topeka Advocate:

Mary Lease, Editorial in the Topeka Advocate

“Today the world stands aghast at the murderous attempt of a Scotch baron (Andrew Carnegie) entrenched and fortified by Republican legislation, to perpetuate a system of social cannibalism, and force, by the aid of Pinkerton cutthroats, the American laborers to accept starvation wages…. We have been told by those who deal in misrepresentations that the farmers were not in sympathy with the wants and demands of laborers in town and city. Let us hurl this falsehood back, and show to the world that the farmers of Kansas are imbued with the spirit of 1776, and in sympathy with the toilers and oppressed humanity everywhere by sending from this state such a trainload of wheat and corn to our Homestead brothers as will make hungry mothers and their little ones laugh with glee.”

Whether the Populists’ appeals for a political alliance were seriously considered by organized labor was debatable. In the summer of 1896, on the eve of the presidential election campaign, prominent labor organizer Samuel Gompers made the following remarks during the AFL’s national convention:

Samuel Gompers, Labor Organizer

“We will soon be in the throes of a political campaign. The passions of men will be sought to be aroused, their prejudices and supposed ignorance played upon and brought into action. The partisan zealot, the political mountebank, the statesman for revenue only, as well as the effervescent, bucolic political party, cure-all sophist and fakir, will be rampant. The dear workingman and his interests will be the theme of all alike, who really seek party advantage and success….

Whatever labor secures now or secured in the past is due to the efforts of the workers themselves in their own organizations—the trades unions on trade union lines, on trade union action. When in previous years the workers were either unorganized or poorly organized, the political trickster scarcely ever have a second thought to the dear workingman and his interests. During the periods of fair or blossoming organization the political soothsayers attempted by cajolery and baiting to work their influence into the labor organizations; to commit them to either party or the other….

In the light of that experience, the American Federation of Labor has always declared and maintained that the unions of labor are above, and should be beyond, the power and influence of political parties.”

Farmers and industrial laborers experienced hardship during the 1890s. Farmers faced debt and marginalization in the modern industrial economy. Events at Homestead and Pullman showed that the capitalists and the federal government worked together to suppress organized labor. Both farmers and industrial workers had specific grievances against the status quo. Populist organizers like Mary Lease hoped that they would unite in a new political coalition under the umbrella of the Populist Party. However, as the presidential election of 1896 approached, prominent labor organizers like Samuel Gompers were skeptical of such overtures, which made it unlikely that urban workers would join farmers in a Populist crusade.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History.” Access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Mary Lease editorial (1892), Retrieved from historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5360/

Grompers, Samuel (1896), Address before the AFL National Convention, Retrieved from gompers.umd.edu/