Table of Contents |

The invention of the printing press led to innovations in printmaking and the proliferation of this form of artwork beginning in 15th-century Europe. The period that you will be looking at today is from 1491 to 1523.

Albrecht Dürer originated from the city of Nuremberg in the Holy Roman Empire (shaded in purple), now the modern-day country of Germany.

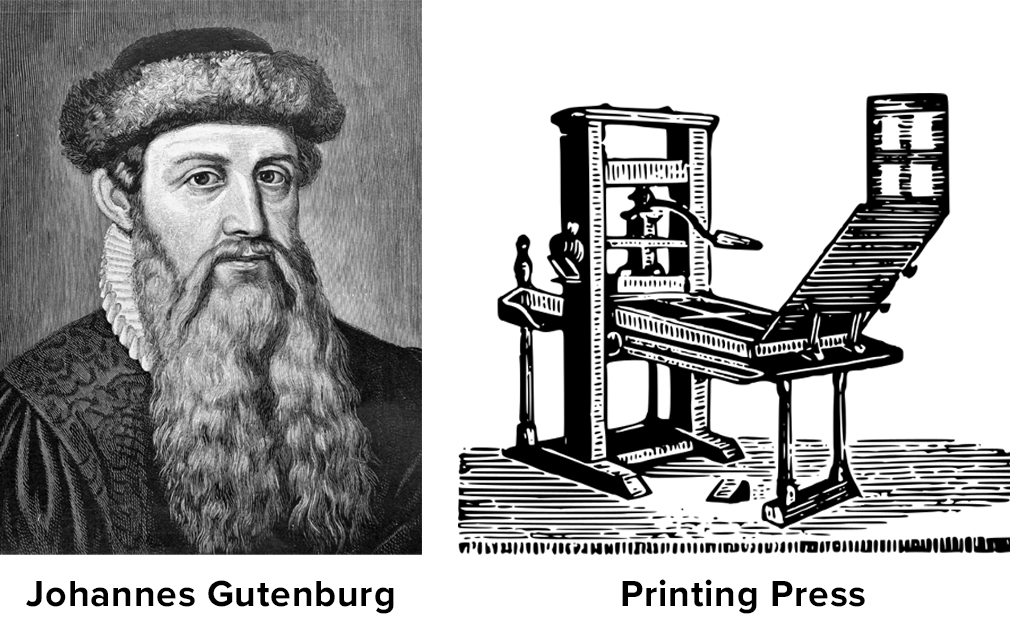

Printmaking was made possible by arguably the most important invention of the modern era: the printing press with movable type, invented by Johannes Gutenberg. While the printing press revolutionized the spread of information, many prints could also be made without the use of the press or moveable type.

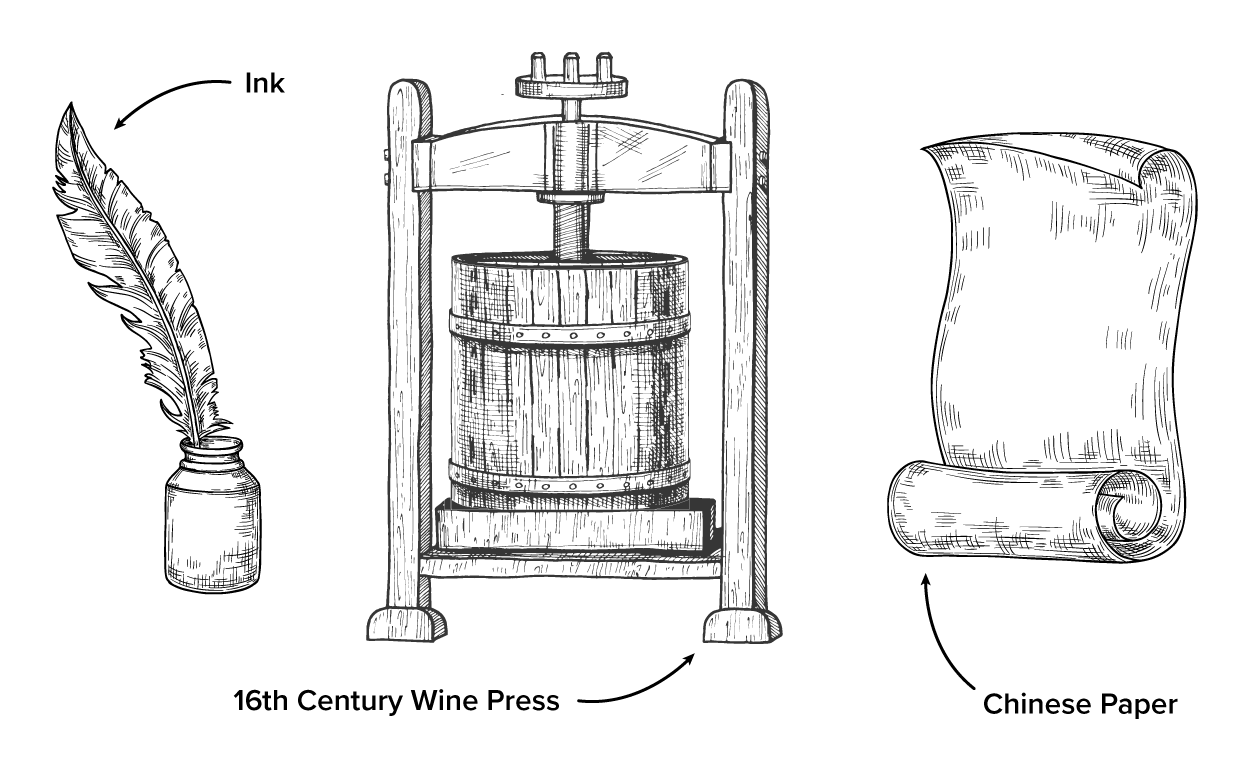

Although movable type had been invented by the Chinese during the Song dynasty (960–1279) centuries earlier, the adaptation of wine and olive oil presses into printing presses using movable type was Gutenberg’s contribution.

Gutenberg eventually perfected the design of his invention, an invention that wouldn’t have been possible without the development of oil-based inks and the availability of paper from China. This single invention was a catalyst in countless areas of human development and was integral in the development of the Renaissance and the spread of literacy and ideas throughout Europe and beyond.

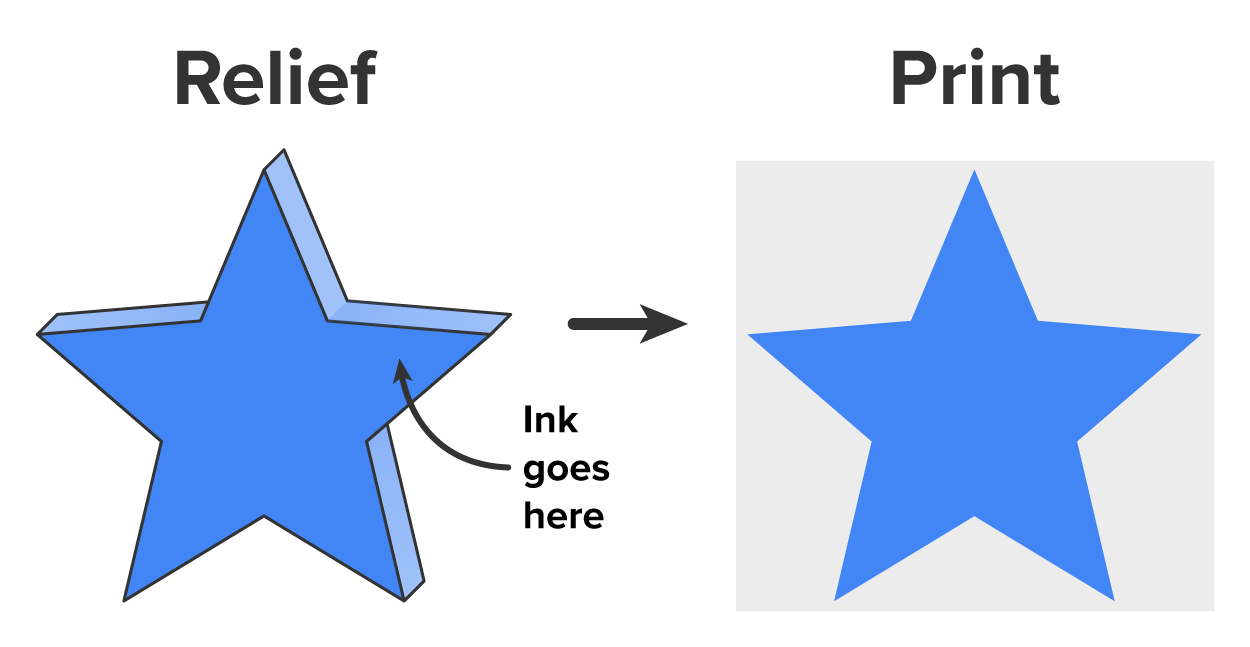

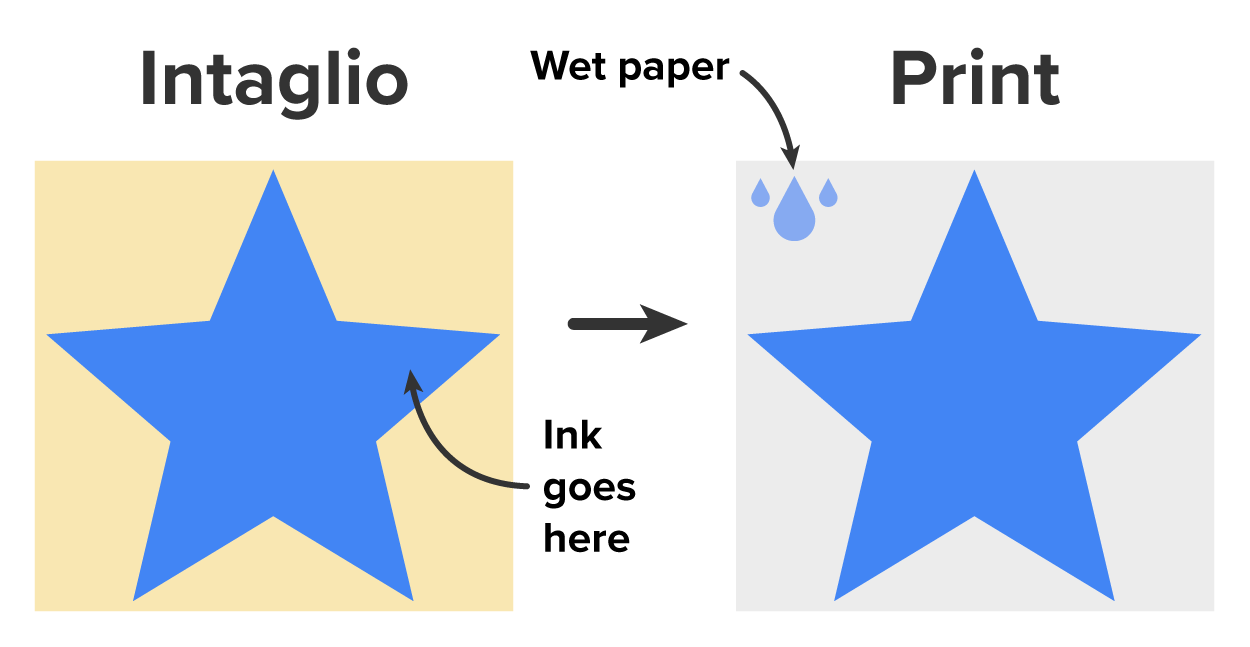

The processes for relief and intaglio printing are similar but have essentially one fundamental difference.

In relief printing, such as block printing, a raised image is carved out of a block of something, usually wood, which would be called a woodcut. Ink is applied to the surface, and the block is then pressed onto a piece of paper, identical to the way in which a rubber stamp works. Think of this process as the opposite of drawing in that the artist carves away the negative space.

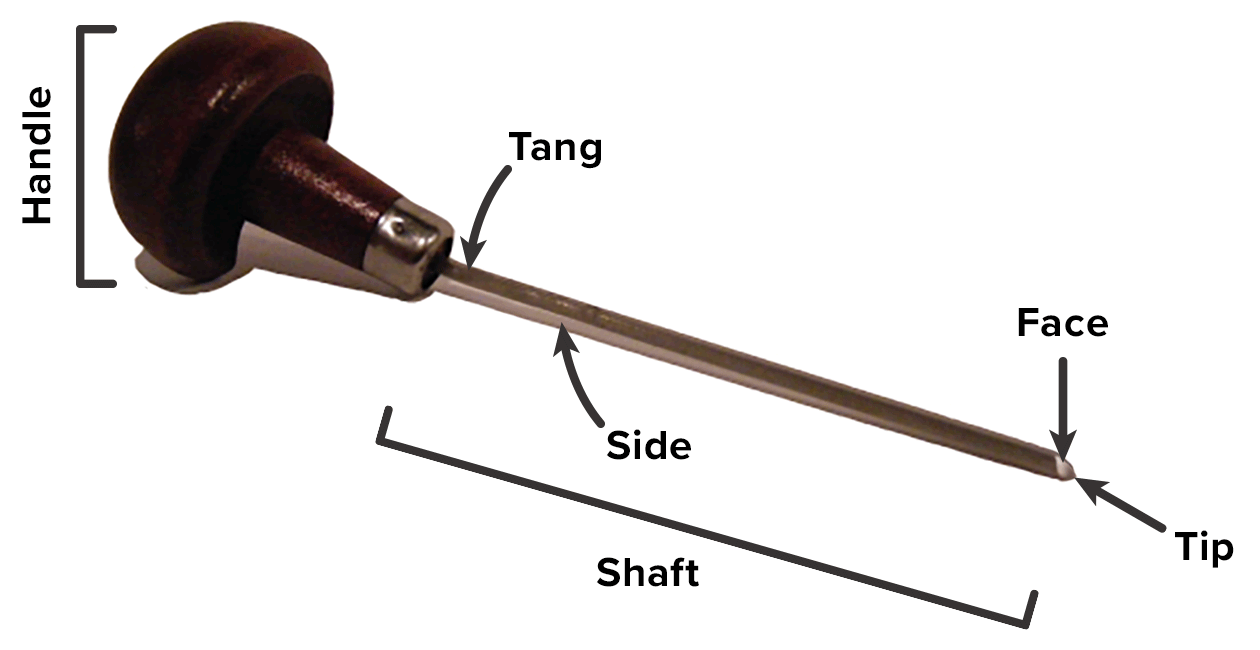

In intaglio printing, which includes the processes of engraving and etching, an image is scratched into a zinc or copper plate, with a sharp, pointed tool called a burin (see image below).

Ink is then placed on top and is poured into the recesses of the plate. Paper is moistened so that it is flexible enough to be pressed into all the little recesses, then is pressed onto the plate. Some prints are manually transferred from the plate to the paper, but others are run through the printing press to add additional pressure.

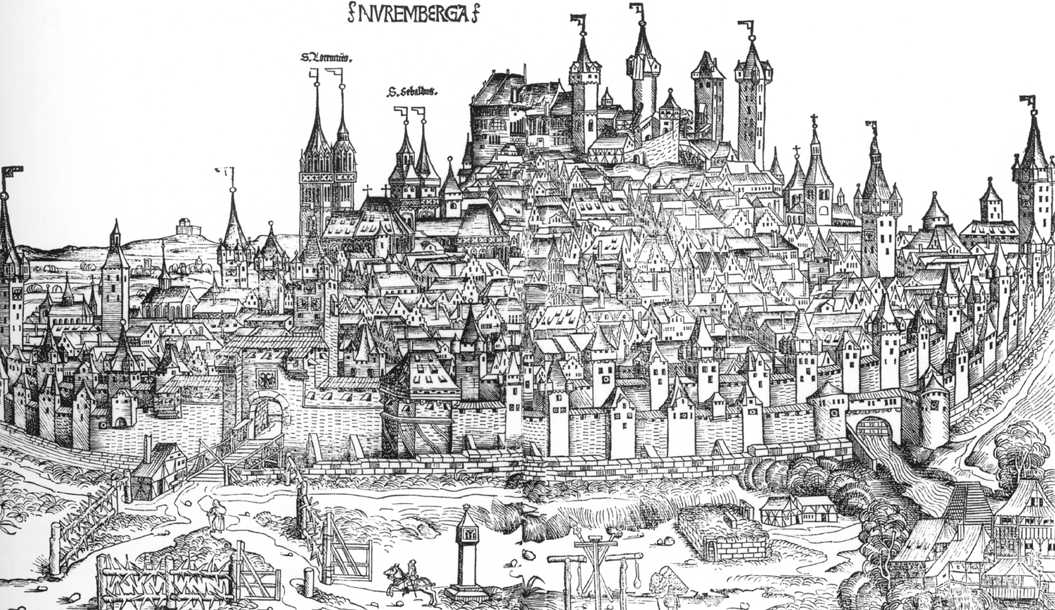

Albrecht Dürer, a master artist in both methods of printing, began his career under the tutelage of illustrator Michael Wolgemut in his hometown of Nuremberg. It’s under Wolgemut’s instruction that Dürer refined his skill in the areas of woodcutting. Dürer was also influenced, though, by the artist Martin Schongauer’s work in etching and therefore became a master in both areas. How do you tell the difference between the two types of prints? The trick is to look at the areas of shadow on the prints. In woodcut prints such as this image of the “View of the City of Nuremberg” page from The Nuremberg Chronicle, there are no areas with true halftones, or shades of gray, because of the thickness of the lines in relief printing. It looks simply black and white. The lines are generally wider and more pronounced in a woodcut relief print. Notice how in this print, everything that reads as white was carved away, and all the black lines were left raised in the block of wood.

“View of the City of Nuremberg” from The Nuremberg Chronicle, Page 100

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich

1493

Relief woodcut

A higher level of detail is possible in intaglio printing, in which true halftones created by the careful application of thin lines in hatching and cross-hatching are possible, resulting in the possibility of creating a more realistic sense of form and depth.

This sense of realism and depth is clearly depicted in this engraving of Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons by Martin Schongauer, in which the hellish creatures bedevil the saint into committing sin. Schongauer, like Dürer, was an accomplished painter as well. Schongauer’s prints were considered the finest examples of engravings in the period before Dürer’s success. Both applied their skills as painters and their eye for detail to the printmaking process.

Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Between 1480 and 1490

Engraving

Although known primarily for his work in printmaking, Albrecht Dürer was an extremely talented artist, as evident in this painting and self-portrait below.

Self-Portrait at 28

Alte Pinakothek, Munich

1500

Oil on lime

One of the most enticing aspects of printmaking was the ability to sell numerous prints. The work of art itself was the plate or block that the image was carved into; however, every printing made from the master carving (or matrix) was considered an original. Dürer took full advantage of this and made a very comfortable living selling multiple prints of his work.

This first image is the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. It is a woodcut, or relief printing, from Dürer’s book on the apocalypse, which is a collection of 14 woodcuts depicting scenes from the Book of Revelation, the final book of the Bible. It was the first book published that was entirely produced by an artist.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

1498

Relief woodcut

Although quite detailed, notice the absence of halftones, or shades of gray—it’s either black or white. This is a consequence of relief printing. The resulting lines are thicker and hold more ink, which in turn creates a darker print. Also notice the signature initials of Dürer located on the bottom of the print—the letter “D” set within a capital “A.”

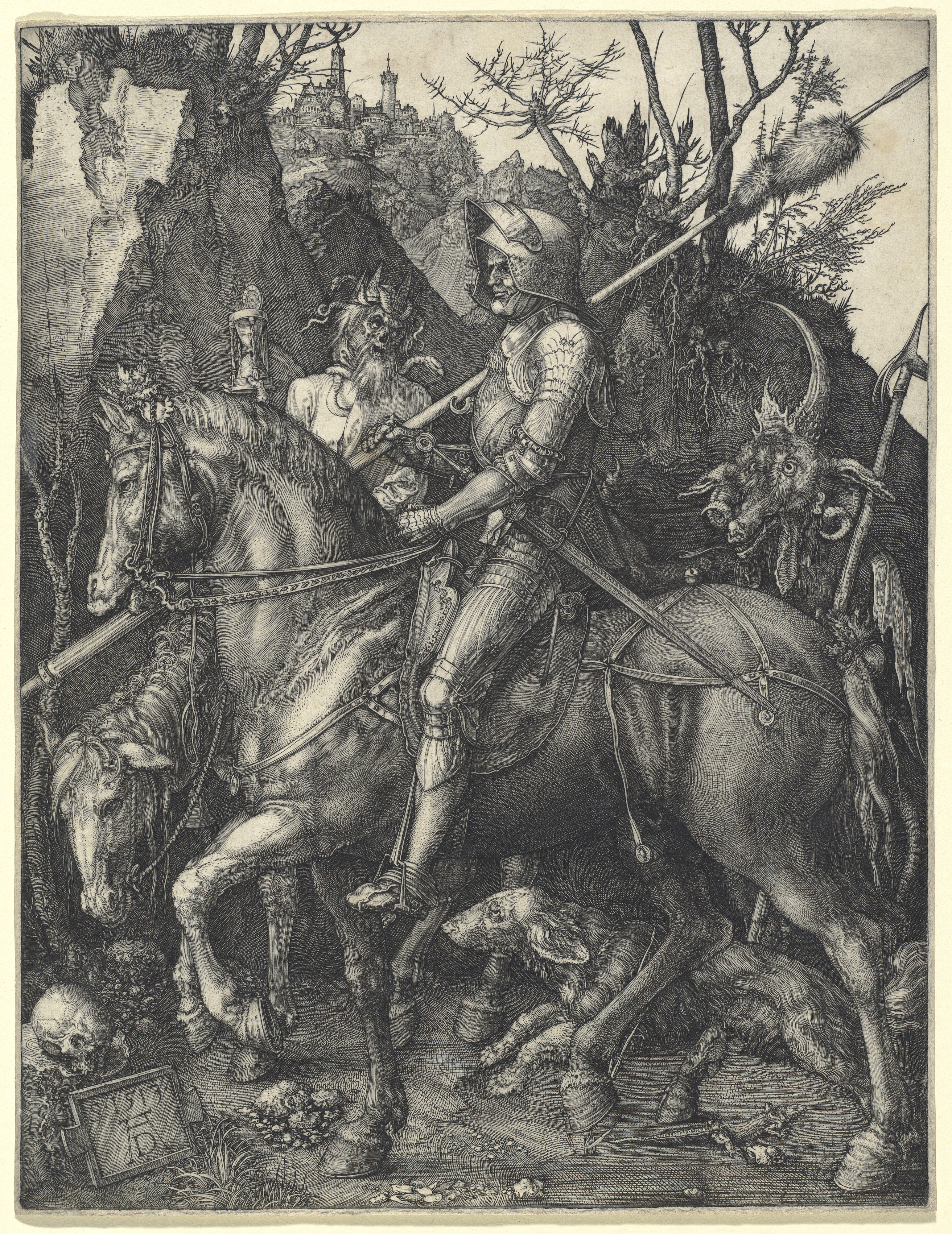

Knight, Death, and the Devil

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

1513

Engraving

Dürer’s Knight, Death, and the Devil is an allegory of the virtuous life. The knight represents the Christian ideal, unperturbed by the threats of death and the temptations of the devil, steadfastly continuing on his righteous path. The detailed, intricate design of the engraving reflects Dürer's masterful skill and his ability to imbue his printmaking with profound philosophical and theological meaning.

This third image of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden demonstrates the effectiveness of halftones in depicting the musculature and definition of the human body. The scene takes place just before the fall of man. Eve is holding an apple and is being coaxed by the serpent—symbolic of the devil—into taking a bite. It’s yet another impressive example of how refined the art of printmaking had become and how the finest examples of prints could rival paintings in their ability to effectively depict depth and sense of form.

Adam and Eve

The Morgan Library and Museum, New York

1504

Engraving

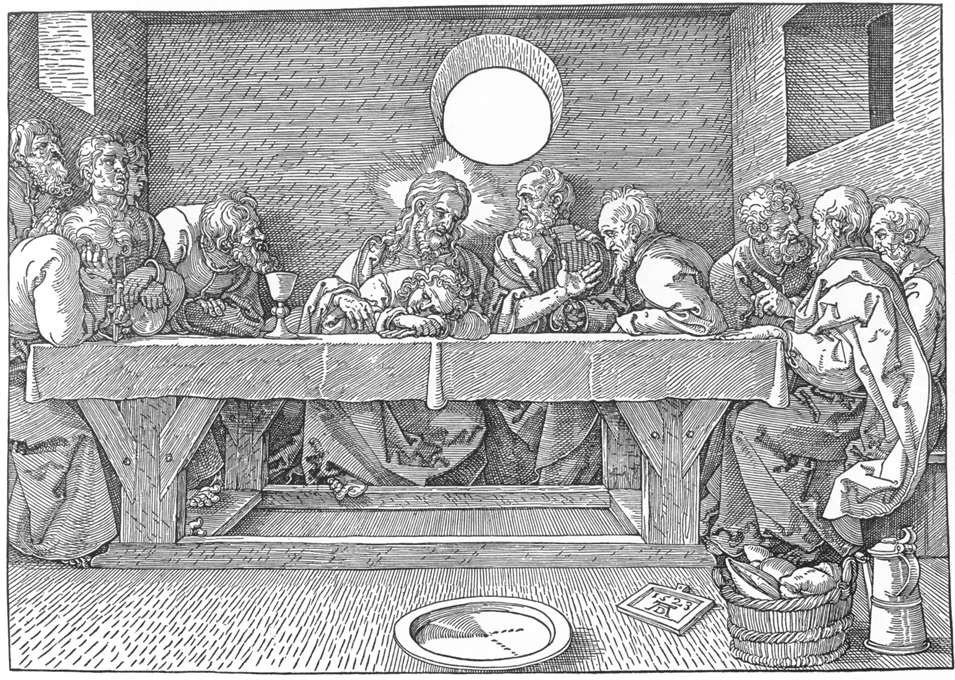

For comparison, take a look at this fourth and final image, an example of a woodcut, so that you can get a sense again of how halftones strongly affect the overall look of an image. Although the sense of depth and roundness of form are convincing here, it’s less realistic in appearance compared to the previous images of Adam and Eve and Knight, Death, and the Devil. Look carefully. The image is only black and white, and without the subtle shades of gray that convey a sense of shadow and three-dimensionality, the image essentially flattens into a two-dimensional image.

The Last Supper

Albertina Museum, Vienna

1523

Relief woodcut

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY IAN MCCONNELL AND TAMORA KOWALSKI FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.