Table of Contents |

Despite overseeing the military and foreign affairs necessary to achieve independence, the inability of the Continental Congress to tax its own citizens made the United States unable to deal with dire economic problems and the social unrest that accompanied them by the late 1780s.

Funding the war effort had proved very difficult for the Continental Congress. Whereas the British could pay in specie (gold or silver coinage), the Americans relied on paper money backed by loans obtained in Europe to pay its soldiers and to conduct everyday business. The Congress printed a large amount of paper money, known as Continental dollars, but the printing of this money, along with the fact that each state printed money of its own, contributed to runaway inflation within the United States. By 1781, inflation was such that 146 Continental dollars were worth only one dollar in gold.

Soldiers in the Continental Army, as well as urban laborers and manufacturers, were among the hardest hit by rampant inflation and the economic recession that accompanied it. One soldier in the Continental Army, Joseph Plumb Martin, recounted how he received no pay in paper money after 1777 and only one month’s payment in specie in 1781. After the war, demobilized soldiers and a number of other laborers searched desperately for work. Manufacturers and exporters also struggled after the war. Upon achieving independence, the United States was no longer subject to the protective economic policies that it had experienced within the British Empire. Thus, British producers and manufacturers now competed with the United States, and their goods flooded American markets by the late 1780s.

A number of farmers, including many in western Massachusetts, were also in a difficult position. Massachusetts and other states raised taxes in order to pay off the debt accrued during the Revolutionary War, and rural landowners bore much of burden. They faced high taxes and debts, which they found nearly impossible to pay with the worthless state and Continental paper money. Many were veterans of the Continental Army who had returned to their farms and families after the fighting ended. Now, unable to pay taxes, they faced losing their homes to foreclosure (seizure of property in lieu of overdue loan payments) .

For several years after the peace in 1783, indebted farmers in Massachusetts petitioned the state legislature for redress. They asked how could people pay their debts and state taxes when paper money proved worthless. They also questioned the location of the state capital in Boston, which catered to the merchant elite and made it difficult for western farmers to attend legislative sessions. Overall, to indebted farmers, the situation by the late 1780s seemed hauntingly familiar. Revolutionaries had defeated Great Britain, but a new self-serving government seemed to have arisen in its place.

In 1786, when the Massachusetts legislature refused to address the petitioners’ requests, citizens took up arms and closed courthouses across the state to prevent foreclosure on farms in debt. The farmers wanted their debts forgiven and they demanded that the 1780 constitution—which was the darling of John Adams and other revolutionary elites suspicious toward democracy—be revised so that citizens beyond the wealthy elite could serve in the legislature.

Many of those who took up arms against the state government were veterans of the War for Independence, including Captain Daniel Shays. Although Shays was only one of many former officers in the Continental Army who took part in the revolt, authorities in Boston singled him out as a ringleader, and the uprising became known as Shays’ Rebellion.

The Massachusetts legislature responded to the closing of the courthouses with a flurry of legislation, much of it designed to punish the rebels. The government offered the rebels clemency if they took an oath of allegiance. Otherwise, local officials were empowered to use deadly force against them without fear of prosecution. Rebels would lose their property, and if any militiamen refused to defend the state, they would be executed.

Despite these measures, the rebellion continued. To address the uprising, Governor James Bowdoin raised a private army of 4,400 men, funded by wealthy Boston merchants, without the approval of the legislature. The climax of Shays’ Rebellion came in January 1787, when the rebels attempted to seize the federal armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. A force loyal to the state defeated them there, although the rebellion continued into February.

Prior to Shays’ Rebellion, there had been been efforts to address the nation’s perilous state. In early 1786, James Madison of Virginia advocated a meeting of states to address the widespread economic problems that plagued the new nation. Heeding Madison’s call, the Virginia legislature invited all 13 states to meet in Annapolis, Maryland, to work on solutions to the issue of commerce between the states. Eight states responded to the invitation, but the resulting Annapolis Convention failed to provide any solutions because only five states actually sent delegates.

Delegates from those states, however, agreed to a plan put forward by Alexander Hamilton for a second convention to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787. Shays’ Rebellion gave greater urgency to the planned convention. In February 1787, in the wake of the uprising in western Massachusetts, the Continental Congress authorized the Philadelphia convention and, this time, all the states except Rhode Island agreed to send delegates.

To men of property throughout the United States, Shays’ Rebellion, along with the dire financial situation that affected the states as well as the national government, suggested that the republic was falling into anarchy, chaos, and stagnation. For instance, by 1787, George Washington believed that current conditions had created "anarchie [and] Confusion," and he openly expressed concern that a demagogue could take over the entire nation.

There were a number of individuals who agreed with Washington and, in the summer of 1787, 55 delegates from 12 states gathered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for what became known as the Constitutional Convention. The delegates included well-known leaders such as Washington and Benjamin Franklin, but they also included younger, less well-known men such as Alexander Hamilton (from New York) and James Madison (from Virginia). The stated purpose of the convention was to amend the Articles of Confederation. Very quickly, however, the attendees decided to create a new framework for a national government: the United States Constitution.

The majority of delegates in Philadelphia agreed on a republican form of government with three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. Much of the debate during the convention centered on the issue of representation in the legislative branch.

| Branch of Government | What? | Who? |

|---|---|---|

| Legislative | Makes the laws | Congress |

| Judicial | Evaluates the laws | Supreme court and other federal courts |

| Executive | Carries out the laws | President, vice president, cabinet members |

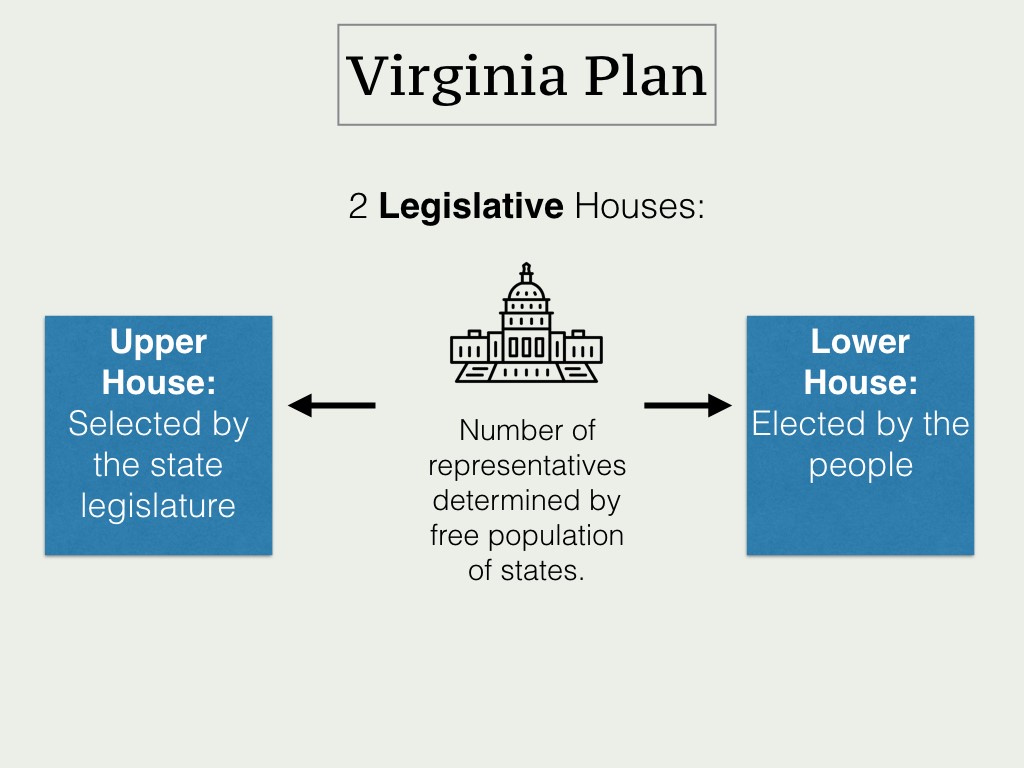

James Madison wrote the Virginia Plan, which proposed a national government with two legislative houses (or bicameral legislature), an executive branch, and a separate judiciary (see diagram below).

Under the Virginia Plan, representation to both houses of the legislature was to be determined by the free population of the states. This proposal alarmed delegates from smaller states, who feared the political dominance of Virginia, New York, and other large or otherwise populous states.

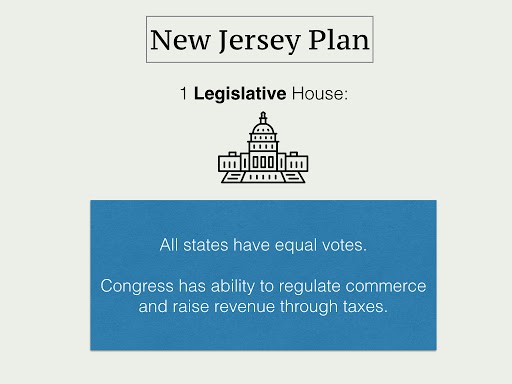

To counter Madison’s scheme, William Paterson introduced the New Jersey Plan, which proposed that all states have equal votes in a unicameral national legislature. He also addressed the economic problems of the day by calling for the Congress to have the power to regulate commerce and to raise revenue through taxes on imports and through postage (see diagram below).

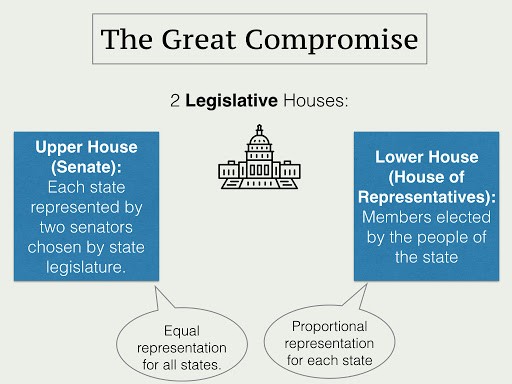

Roger Sherman from Connecticut offered a compromise to break the deadlock over the thorny question of representation. He proposed the Connecticut Compromise, also known as the Great Compromise.

The question of slavery stood as another major issue for the Constitutional Convention because delegates from southern states wanted enslaved people to be counted along with White people, or “free inhabitants,” when determining a state’s total population. This, in turn, would augment the number of representatives accorded to those states in the House of Representatives.

Some northern delegates, such as Gouverneur Morris of New York, hated slavery and did not even want the term included in the new national plan of government. Meanwhile, the delegates who represented slaveholders defended the institution by arguing that it increased the production of commodities that the United States could export, thus adding important revenue to the treasury. They also argued that slavery imposed great burdens upon slaveholders and, as a result, they deserved special consideration, including that of counting enslaved people for the purposes of representation.

Convention delegates ultimately reached a series of compromises in which the Constitution did not mention slavery directly but still protected the institution. The Constitution stated that the U.S. government could not introduce any legislation against the international slave trade for at least twenty years (1808). The document also featured a fugitive slave provision, stating "No person held to Service or Labour [i.e. slavery] in one State…escaping into another, shall…be discharged from such Service or Labour." Instead, the Constitution required that such individuals should "be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due" or, in other words, that runaways should be returned to their owners.

Most notably, the Convention agreed to the Three-Fifths Compromise.

Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution

Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution stipulated that “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several states...according to their respective Number, which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free Persons, including those bound for service for a Term of Years [white servants], and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other persons.”

Since representation in the House of Representatives was based on the population of a state, the Three-Fifths Compromise granted extra political power to states with large enslaved populations.

The debate over slavery during the Constitutional Convention revealed that the institution was increasingly coming into question, especially in northern states. However, by incorporating the Three-Fifths Compromise and other provisions that protected racial slavery, it was also clear that the Constitutional Convention would not end the institution. Rather, the concessions regarding slavery would enable enslavers to look to the national government to protect their institution.

Finally, many of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention continued to have serious reservations about democracy, which they believed promoted anarchy. To allay these fears, the Constitution featured several provisions to limit the voice of the people, the most notable of which being the Electoral College.

Convention delegates knew that George Washington would be elected the first President of the United States. After him, though, the decision would not be as clear and the delegates did not believe that such a decision should be left to the American people.

The original intent of the Electoral College was as follows:

Critics of the Electoral College argue that the process prevents the direct election of the President. However, given the context of the late 1780s, this was exactly what the delegates to the Constitutional Convention desired. The College was an expression of the Convention’s consensus on elite, republican rule. Designated electors or, in the absence of a majority, Congress, were expected to identify the wisest, most virtue-minded individuals to lead the nation. The people were expected to trust the judgment of their representatives.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL