Table of Contents |

Genome mapping is the process of finding the locations of genes on each chromosome. The maps that genome mapping create are comparable to the maps that we use to navigate streets. A genetic map is an illustration that lists genes and their location on a chromosome. Genetic maps provide the big picture (similar to an interstate highway map) and use genetic markers (similar to landmarks). A genetic marker is a gene or sequence on a chromosome that co-segregates (shows genetic linkage) with a specific trait. Early geneticists called this linkage analysis. Physical maps present the intimate details of smaller chromosome regions (similar to a detailed road map). A physical map is a representation of the physical distance, in nucleotides, between genes or genetic markers. Both genetic linkage maps and physical maps are required to build a genome’s complete picture. Having a complete genome map of the genome makes it easier for researchers to study individual genes.

IN CONTEXT

The Human Genome Project was a project that mapped the complete human genome using DNA sequencing. This was a huge project because there are over three billion nucleotide bases in a total of about 21,500 genes. The knowledge of this information is very helpful in the research of genetic disorders and medicine.

The 21,500 genes mentioned above code for all the proteins we make. However, if you add all the nucleotides from all those gene sequences together, nucleotides that code for genes only make up 2% of all the nucleotides in our genome. The rest of the DNA is non-coding DNA. Historically, the non-coding DNA has been referred to as "junk DNA" because it doesn't code for proteins. However, we are beginning to discover that it has subtler functions, such as modulating the timing and location of protein expression. Biologists are working on trying to figure out what the purpose of this junk DNA is.

Human genome maps help researchers in their efforts to identify human disease-causing genes related to illnesses like cancer, heart disease, and cystic fibrosis. We can use genome mapping in a variety of other applications, such as using live microbes to clean up pollutants or even prevent pollution, and to produce higher crop yields or develop plants that better adapt to climate change.

The National Center for Biotechnology Information houses a widely used genetic sequence database called GenBank where researchers deposit genetic information for public use. Upon publication of sequence data, researchers upload it to GenBank, giving other researchers access to the information. The collaboration allows researchers to compare newly discovered or unknown sample sequence information with the vast array of sequence data that already exists.

A sequence alignment is an arrangement of proteins, DNA, or RNA. Scientists use it to identify similar regions between cell types or species, which may indicate function or structure conservation. We can use sequence alignments to construct phylogenetic trees.

DNA sequencing is a tool that greatly contributes to our ability to map genomes, and you will learn more about some of the more common DNA sequencing methods throughout this lesson. However, it is important to keep mind that the list of methods described here is not exhaustive, and there are many different sequencing techniques and technologies that have been developed and that are in development, as our understanding of genomics has been exponentially increasing over the past few decades.

Until the 1990s, the sequencing of DNA (reading the sequence of DNA) was a relatively expensive and long process. Using radiolabeled nucleotides also compounded the problem because of safety concerns. With currently available technology and automated machines, the process is cheaper, safer, and can be completed in a matter of hours. Fred Sanger developed the sequencing method used for the human genome sequencing project, and that method is widely used. For his work on DNA sequencing, Sanger received a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980.

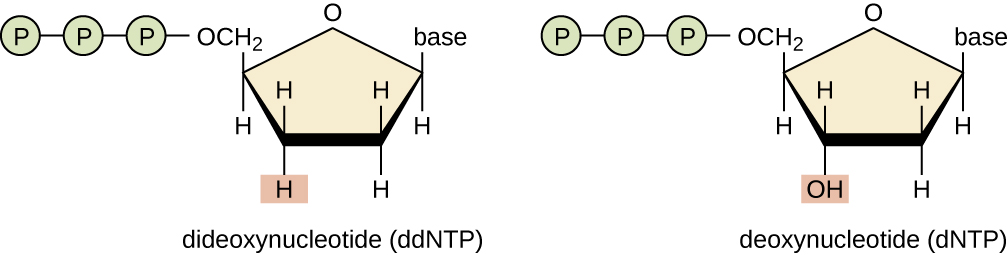

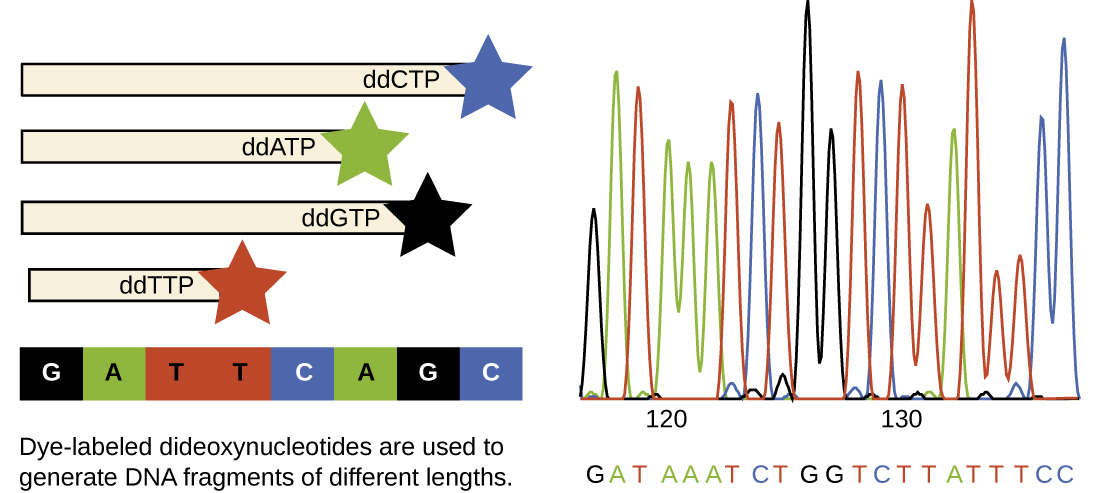

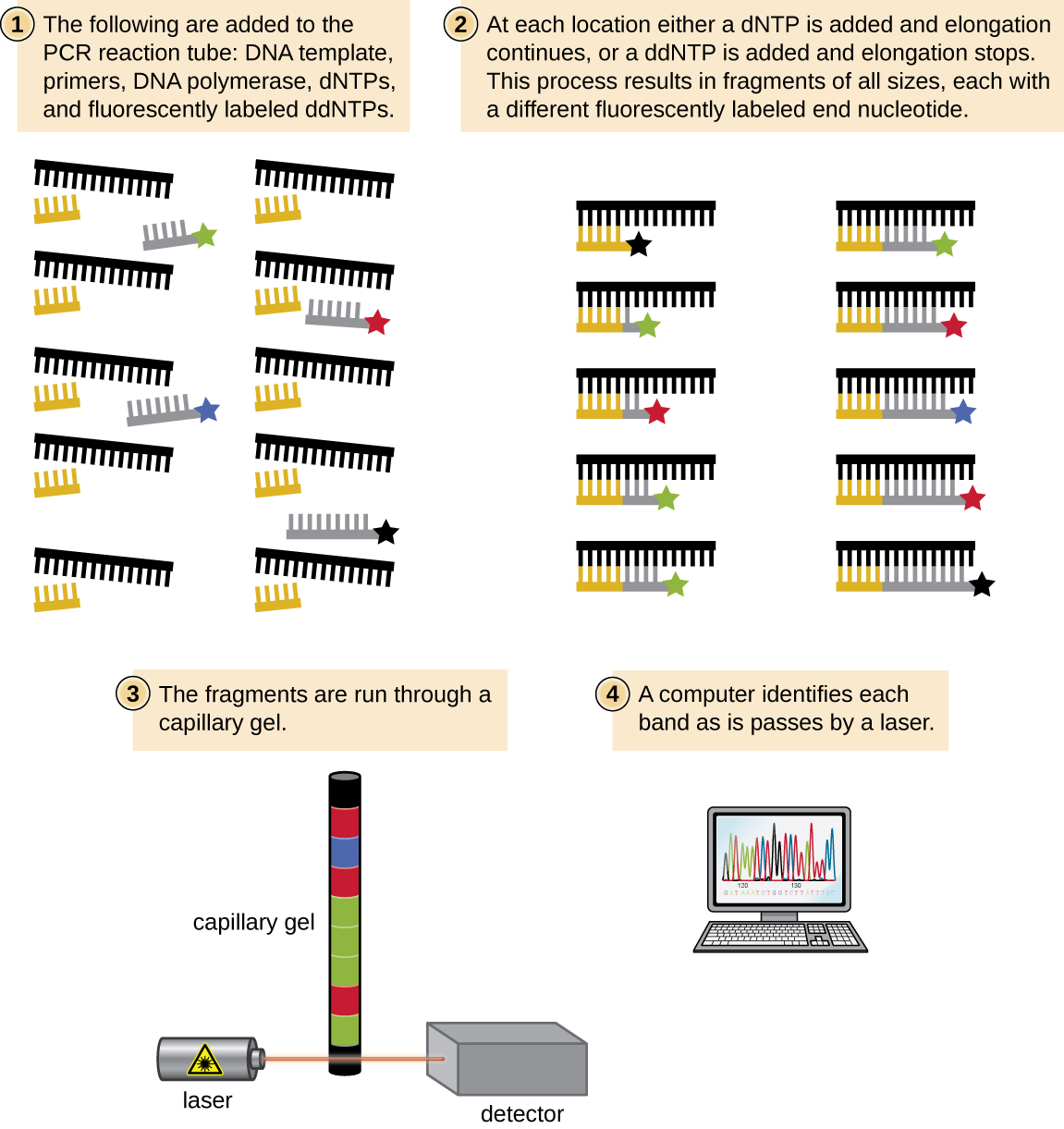

This sequencing method is known as the dideoxy chain termination method, or “Sanger sequencing,” after Sanger. This method is based on the use of chain terminators, the dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs). The ddNTPs differ from the deoxynucleotides by the lack of a free 3′-OH group on the five-carbon sugar. If a ddNTP is added to a growing DNA strand, the chain cannot be extended any farther because the free 3′-OH group needed to add another nucleotide is not available. By using a predetermined ratio of deoxynucleotides to ddNTPs, it is possible to generate DNA fragments of different sizes. This type of sequencing is commonly used to examine individual genetic markers or a small subset of genetic markers.

The chain termination method involves DNA replication of a single-stranded template with the use of a DNA primer to initiate synthesis of a complementary strand, DNA polymerase, a mix of the four regular deoxynucleotide (dNTP) monomers, and a small proportion of dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs), each labeled with a molecular beacon. The ddNTPs are monomers missing a hydroxyl group (-OH) at the site at which another nucleotide usually attaches to form a chain. Every time a ddNTP is randomly incorporated into the growing complementary strand, it terminates the process of DNA replication for that particular strand. This results in multiple short strands of replicated DNA that are each terminated at a different point during replication.

Most methods of DNA analysis, including DNA sequencing, require large amounts of a specific DNA fragment. In the past, large amounts of DNA were produced by growing the host cells of a genomic library. However, libraries take time and effort to prepare, and DNA samples of interest often come in minute quantities. Large amounts of DNA are now typically obtained by a process called polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which permits rapid amplification in the number of copies of specific DNA sequences for further analysis.

IN CONTEXT

One of the most powerful techniques in molecular biology, PCR was developed in 1983 by Kary Mullis while at Cetus Corporation. PCR has specific applications in research, forensic, and clinical laboratories, including:

- determining the sequence of nucleotides in a specific region of DNA

- amplifying a target region of DNA for cloning into a plasmid vector

- identifying the source of a DNA sample left at a crime scene

- analyzing samples to determine paternity

- comparing samples of ancient DNA with modern organisms

- determining the presence of difficult to culture, or unculturable, microorganisms in humans or environmental samples

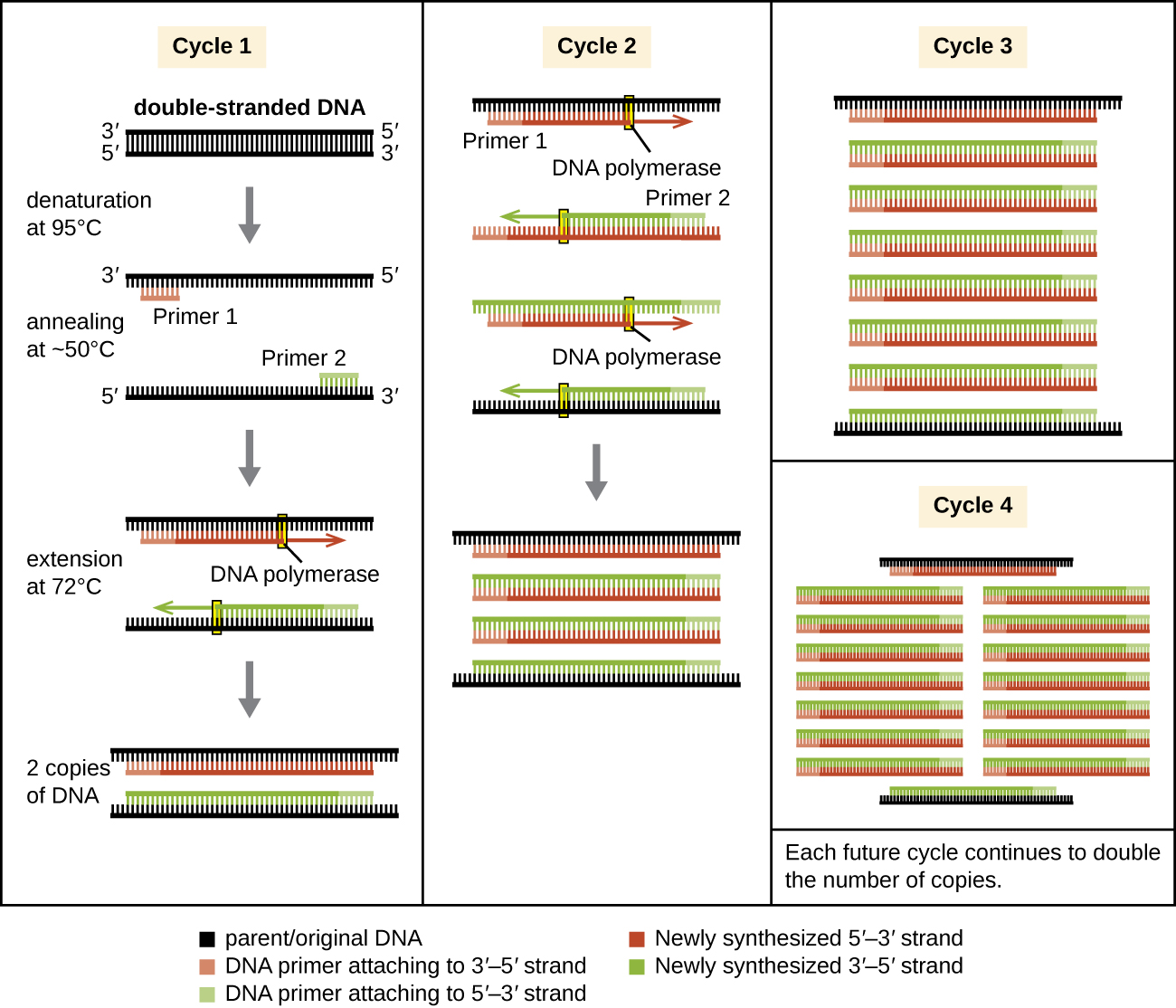

PCR is an in vitro laboratory technique that takes advantage of the natural process of DNA replication. The heat-stable DNA polymerase enzymes used in PCR are derived from hyperthermophilic prokaryotes. Taq DNA polymerase, commonly used in PCR, is derived from the Thermus aquaticus bacterium isolated from a hot spring in Yellowstone National Park. DNA replication requires the use of primers for the initiation of replication to have free 3′-hydroxyl groups available for the addition of nucleotides by DNA polymerase. DNA primers are used that bind to specific targets due to complementarity between the target DNA sequence and the primer.

PCR occurs over many cycles, each containing three steps: denaturation, annealing, and extension. Each step occurs at specific temperatures. Machines called thermal cyclers are used for PCR; these machines can be programmed to automatically cycle through the temperatures required at each step. Typically, PCR protocols include 25–40 cycles, allowing for the amplification of a single target sequence by tens of millions to over a trillion.

The process of how PCR works is shown in the image below.

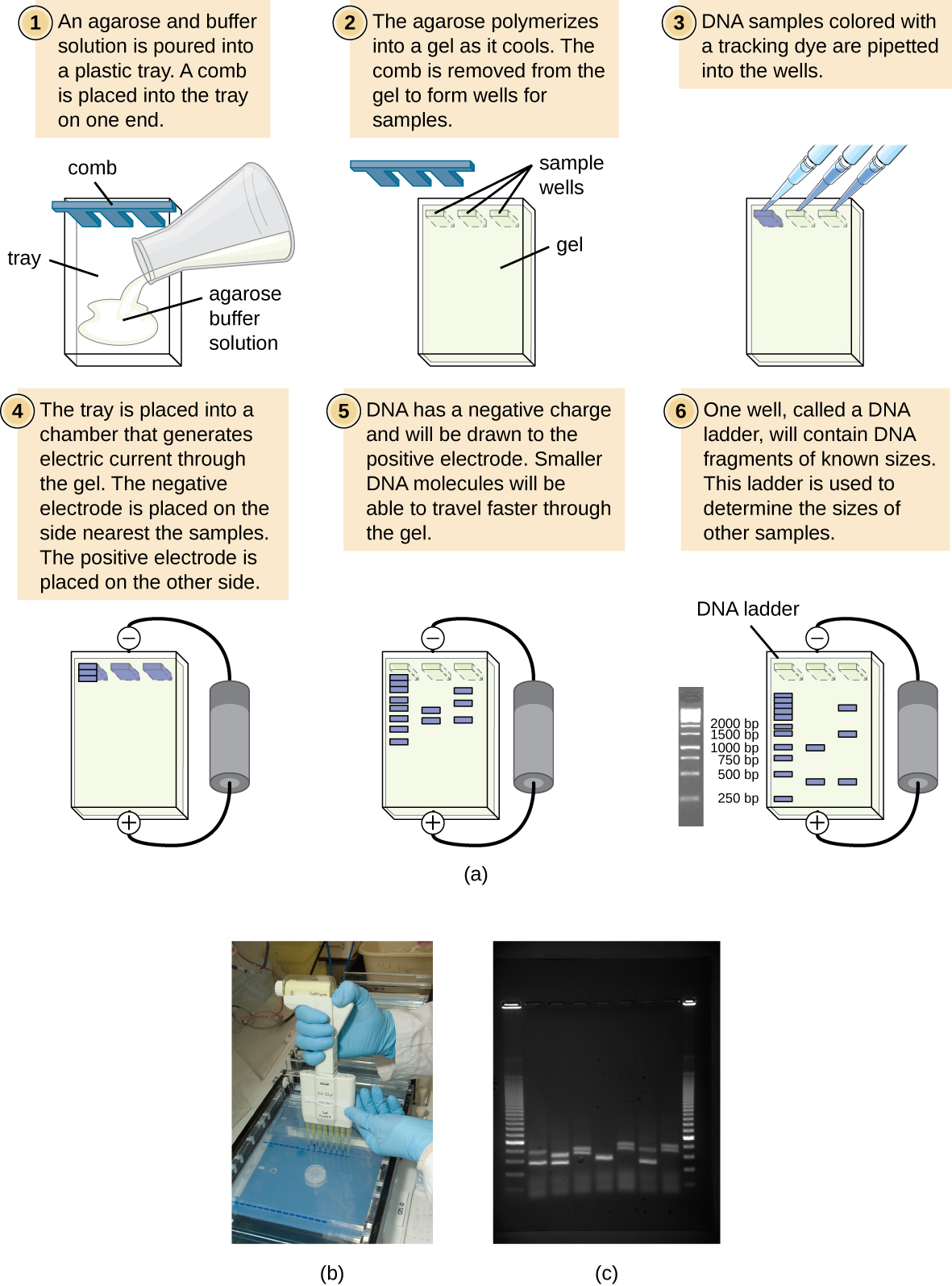

Gel electrophoresis is a technique used to separate DNA fragments of different sizes.

IN CONTEXT

There are a number of situations in which a researcher might want to physically separate a collection of DNA fragments of different sizes. The resulting size and fragment distribution pattern can often yield useful information about the sequence of DNA bases that can be used, much like a bar-code scan, to identify the individual or species to which the DNA belongs. It can also be used to infer if PCR amplified a desired DNA segment.

There are a few different types of gel electrophoresis, but the gel is often made of a chemical called agarose (a polysaccharide polymer extracted from seaweed). When a PCR product is subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, the multiple newly replicated DNA strands form a ladder of differing sizes. Because the ddNTPs are labeled, each band on the gel reflects the size of the DNA strand when the ddNTP terminated the reaction.

To perform agarose gel electrophoresis, the DNA is loaded on the gel, and electric current is applied. The DNA has a net negative charge and moves from the negative electrode toward the positive electrode. The electric current is applied for sufficient time to let the DNA separate according to size; the smallest fragments will be farthest from the well (where the DNA was loaded), and the heavier molecular weight fragments will be closest to the well. Once the DNA is separated, the gel is stained with a DNA-specific dye for viewing it.

The image below describes the process of agarose gel electrophoresis.

Gel electrophoresis tells you what the size of a DNA fragment is, but not the specific nucleotide sequence. To determine the nucleotide sequence, the PCR product must be sequenced.

In Sanger’s day, four reactions were set up for each DNA molecule being sequenced, each reaction containing only one of the four possible ddNTPs. Each ddNTP was labeled with a radioactive phosphorus molecule. The products of the four reactions were then run in separate lanes side by side on long, narrow polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels, and the bands of varying lengths were detected by autoradiography. Today, this process has been simplified with the use of ddNTPs, each labeled with a different colored fluorescent dye or fluorochrome, in one sequencing reaction containing all four possible ddNTPs for each DNA molecule being sequenced. These fluorochromes are detected by fluorescence spectroscopy. The fluorescence color of each band is determined as it passes by the detector, producing the nucleotide sequence of the template strand.

Although there have been significant advances in the medical sciences in recent years, doctors are still confounded by some diseases, and they are using whole-genome sequencing to discover the root of the problem. Whole-genome sequencing is a process that determines an entire genome’s DNA sequence. Whole-genome sequencing is a brute-force approach to problem solving when there is a genetic basis at the core of a disease. Several laboratories now provide services to sequence, analyze, and interpret entire genomes.

For example, whole-exome sequencing is a lower-cost alternative to whole-genome sequencing. In exome sequencing, the doctor sequences only the DNA’s coding, exon-producing regions.

IN CONTEXT

In 2010, doctors used whole-exome sequencing to save a young boy whose intestines had multiple mysterious abscesses. The child had several colon operations with no relief. Finally, they performed whole-exome sequencing, which revealed a defect in a pathway that controls apoptosis (programmed cell death). The doctors used a bone-marrow transplant to overcome this genetic disorder, leading to a cure for the boy. He was the first person to receive successful treatment based on a whole-exome sequencing diagnosis. Today, human genome sequencing is more readily available, and results are available within two days for about $1,000.

In shotgun sequencing, several DNA fragment copies are cut randomly into many smaller pieces (somewhat like what happens to a round shot cartridge when fired from a shotgun). All of the segments are sequenced using the chain termination method. Then, with sequence computer assistance, scientists can analyze the fragments to see where their sequences overlap. By matching overlapping sequences at each fragment’s end, scientists can reform the entire DNA sequence. A larger sequence that is assembled from overlapping shorter sequences is called a contig.

Originally, shotgun sequencing only analyzed one end of each fragment for overlaps. This was sufficient for sequencing small genomes. However, the desire to sequence larger genomes, such as that of a human, led to developing double-barrel shotgun sequencing, or pairwise-end sequencing. In pairwise-end sequencing, scientists analyze each fragment’s end for overlap. Pairwise-end sequencing is, therefore, more cumbersome than shotgun sequencing, but it is easier to reconstruct the sequence because there is more available information.

Since 2005, automated sequencing techniques used by laboratories are under the umbrella of next-generation sequencing (also called deep sequencing or massively parallel sequencing), which is a group of automated techniques used for rapid DNA sequencing. These automated low-cost sequencers can generate sequences of hundreds of thousands or millions of short fragments (25 to 500 base pairs) in the span of one day. These sequencers use sophisticated software to get through the cumbersome process of putting all the fragments in order.

Although several variants of next-generation sequencing technologies are made by different companies (for example, 454 Life Sciences’ pyrosequencing and Illumina’s Solexa technology), they all allow millions of bases to be sequenced quickly, making the sequencing of entire genomes relatively easy, inexpensive, and commonplace. Overall, these technologies continue to advance rapidly, decreasing the cost of sequencing and increasing the availability of sequence data from a wide variety of organisms quickly.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) OPENSTAX “BIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/BIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. (2) OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/MICROBIOLOGY/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSING (1 & 2): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.