Table of Contents |

Lipids are large molecules and generally are nonpolar and not water-soluble. Like carbohydrates and protein, lipids are broken into small components for absorption. Since most of our digestive enzymes are water-based, how does the body break down fat and make it available for the various functions it must perform in the human body?

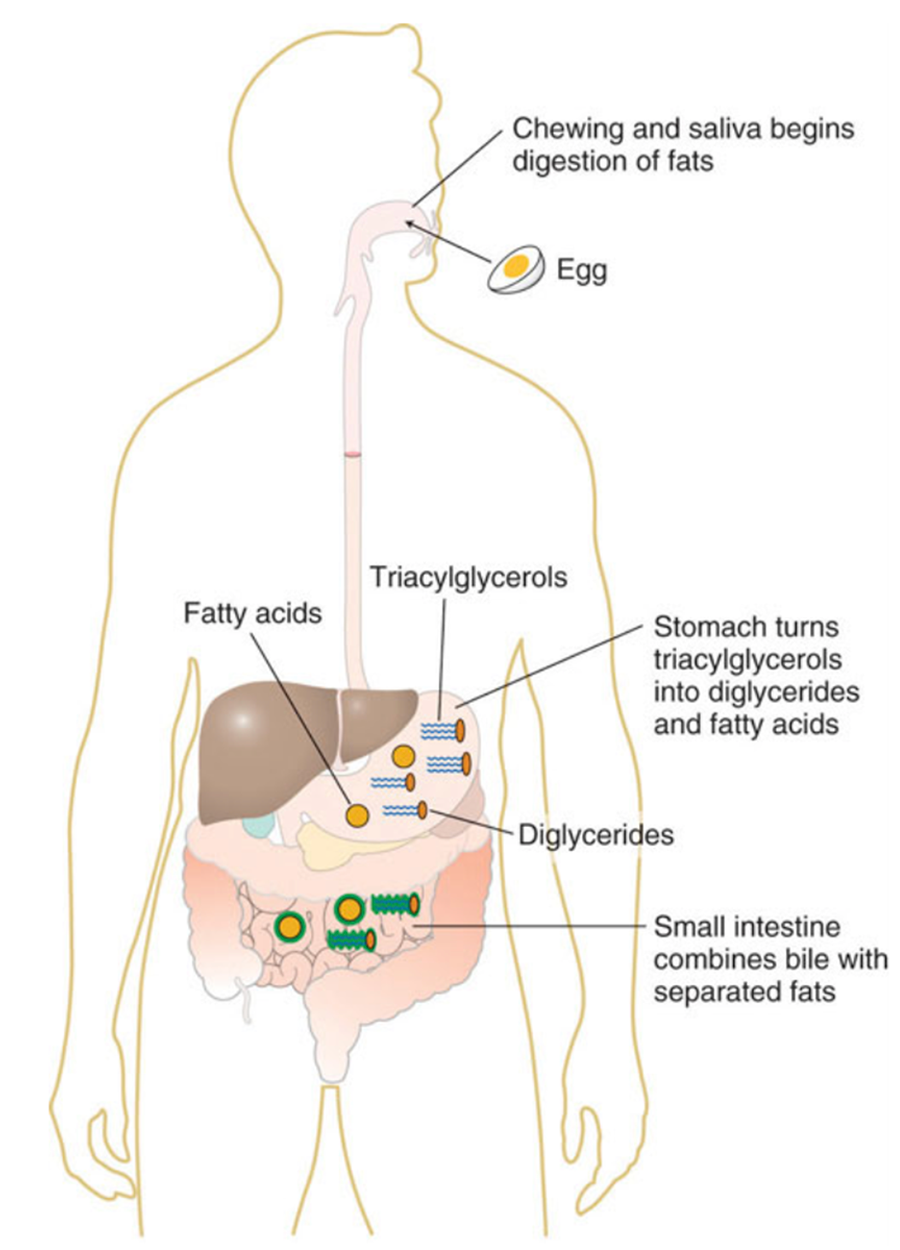

In the stomach, gastric lipase starts to break down triacylglycerols into diglycerides and fatty acids. Within two to four hours after eating a meal, roughly 30 percent of the triacylglycerols are converted to diglycerides and fatty acids. The stomach’s churning and contractions help to disperse the fat molecules, while the diglycerides derived in this process act as further emulsifiers. However, even amid all of this activity, very little fat digestion occurs in the stomach.

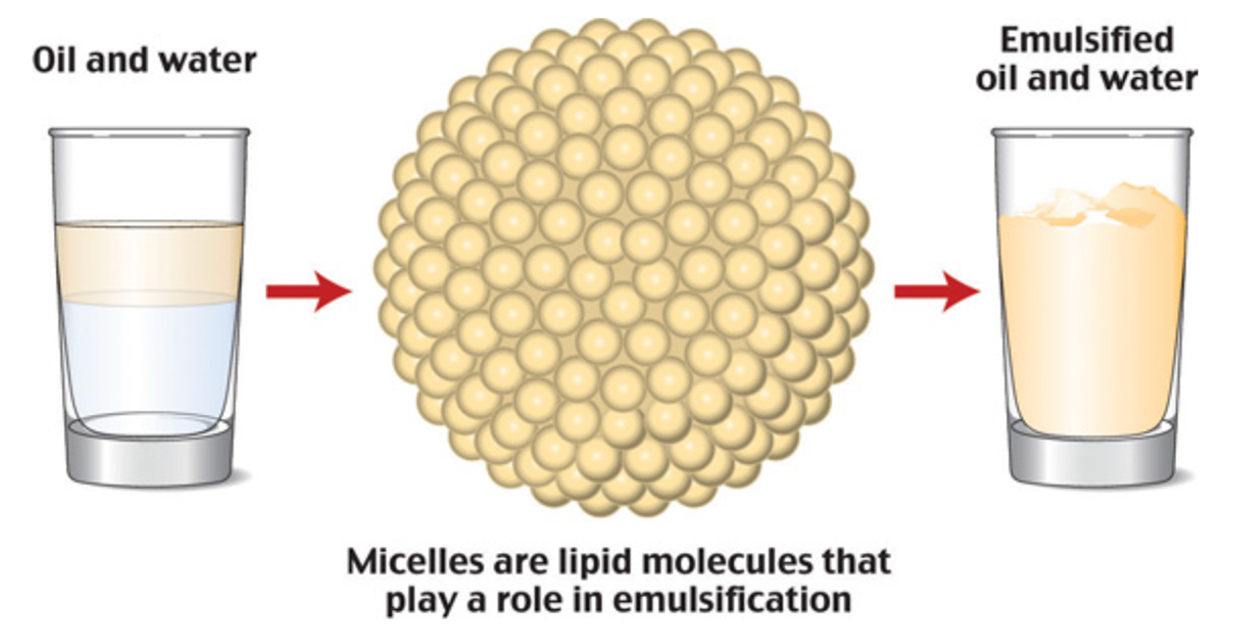

As stomach contents enter the small intestine, the digestive system sets out to manage a small hurdle, namely, to combine the separated fats with its own watery fluids. The solution to this hurdle is bile. Bile contains bile salts, lecithin, and substances derived from cholesterol so it acts as an emulsifier. It attracts and holds onto fat while it is simultaneously attracted to and held on to by water. Emulsification increases the surface area of lipids over a thousand-fold, making them more accessible to the digestive enzymes.

IN CONTEXT

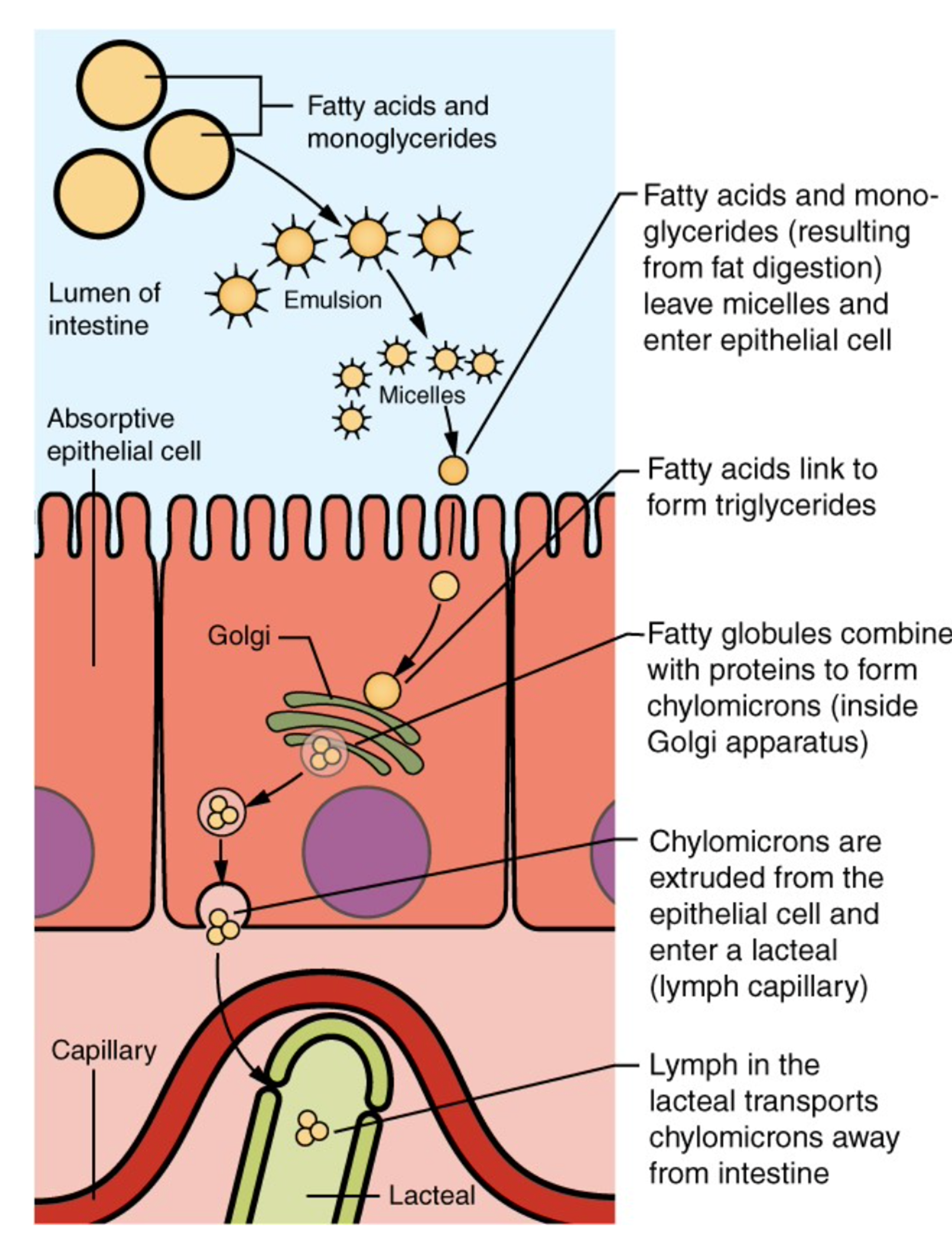

Once the stomach contents have been emulsified, fat-breaking enzymes work on the triacylglycerols and diglycerides to sever fatty acids from their glycerol foundations. As pancreatic lipase enters the small intestine, it breaks down the fats into free fatty acids and monoglycerides. Yet again, another hurdle presents itself. How will the fats pass through the watery layer of mucous that coats the absorptive lining of the digestive tract? As before, the answer is bile. Bile salts envelop the fatty acids and monoglycerides to form micelles. Micelles have a fatty acid core with a water-soluble exterior. This allows efficient transportation to the intestinal microvillus. Here, the fat components are released and disseminated into the cells of the digestive tract lining.

Just as lipids require special handling in the digestive tract to move within a water-based environment, they require similar handling to travel in the bloodstream. Inside the intestinal cells, the monoglycerides and fatty acids reassemble themselves into triacylglycerols. Triacylglycerols, cholesterol, and phospholipids form lipoproteins when joined with a protein carrier. Lipoproteins have an inner core that is primarily made up of triacylglycerols and cholesterol esters (a cholesterol ester is a cholesterol linked to a fatty acid). The outer envelope is made of phospholipids interspersed with proteins and cholesterol. Together they form a chylomicron, which is a large lipoprotein that now enters the lymphatic system and will soon be released into the bloodstream via the jugular vein in the neck. Chylomicrons transport food fats perfectly through the body’s water-based environment to specific destinations such as the liver and other body tissues.

Cholesterols are poorly absorbed when compared to phospholipids and triacylglycerols. Cholesterol absorption is aided by an increase in dietary fat components and is hindered by high fiber content. This is the reason that a high intake of fiber is recommended to decrease blood cholesterol.

About 95 percent of lipids are absorbed in the small intestine. Bile salts not only speed up lipid digestion, they are also essential to the absorption of the end products of lipid digestion. Short-chain fatty acids are relatively water soluble and can enter the absorptive cells (enterocytes) directly. Despite being hydrophobic, the small size of short-chain fatty acids enables them to be absorbed by enterocytes via simple diffusion, and then take the same path as monosaccharides and amino acids into the blood capillary of a villus.

Before the prepackaged food industry, fitness centers, and weight-loss programs, our ancestors worked hard to even locate a meal. Today, this is why we can go long periods without eating, whether we are sick with a weak appetite, our physical activity level has increased, or there is simply no food available. Our bodies reserve fuel for a rainy day.

In a similar manner, much of the triacylglycerols the body receives from food is transported to fat storehouses within the body if not used for producing energy. The chylomicrons are responsible for shuttling the triacylglycerols to various locations such as the muscles, breasts, external layers under the skin, and internal fat layers of the abdomen, thighs, and buttocks where they are stored by the body in adipose tissue for future use.

Once inside the adipose cells, the fatty acids and glycerol are reassembled into triacylglycerols and stored for later use. Muscle cells may also take up the fatty acids and use them for muscular work and generating energy. When a person’s energy requirements exceed the amount of available fuel presented from a recent meal or extended physical activity has exhausted glycogen energy reserves, fat reserves are retrieved for energy utilization.

As the body calls for additional energy, the adipose tissue responds by dismantling its triacylglycerols and dispensing glycerol and fatty acids directly into the blood. Upon receipt of these substances, the energy-hungry cells break them down further into tiny fragments. These fragments go through a series of chemical reactions that yield energy, carbon dioxide, and water.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM LUMEN LEARNING’S “NUTRITION FLEXBOOK”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-nutrition/. LICENSE: creative commons attribution 4.0 international.