In this lesson, you will learn about the propositions and variations in differential association theory and how this theory is applied in the field of criminology. Specifically, this lesson will cover the following:

1. Differential Association Theory

In the early 1930s, Jerome Michael and Mortimer J. Adler (1933) published a report titled Crime, Law, and Social Science that examined the state of knowledge in criminology and criminal justice. The conclusions from this report suggested that criminological research was futile and reflected the poor theoretical development and research methods at the time (Michael & Adler, 1933). Partially in response to this critique, Edwin H. Sutherland argued that the field needed a sociological approach to the theory that could be empirically tested and explain known correlates of crime (e.g., gender, race, and socioeconomic status).

-

EXAMPLE

A meaningful theory of crime needs to be able to explain why offending behavior is concentrated in adolescence and young adulthood and declines subsequently thereafter.

Now recognized as one of the most important criminologists of the 20th century, Sutherland (1947) developed differential association theory. Sutherland aimed to establish an individual-level sociological theory of crime that refuted the claims that criminality was inherited. Instead, Sutherland explored the role of the immediate social environment, which was often discounted in broader macro-level theories, and suggested that behavior was primarily learned within small group settings.

-

- Differential Association Theory

- A theory proposing that through interaction with others, individuals learn the values, attitudes, techniques, and motives for criminal behavior.

1a. The Nine Propositions

Importantly, Sutherland (1947) sought to articulate a formal theory by presenting propositions that could be used to explain how individuals come to engage in crime. In his Principles of Criminology textbook, Sutherland articulated the following nine propositions of differential association theory:

-

Criminal behavior is learned. Stated differently, people are not born criminals. Experience and social interactions inform whether individuals engage in crime.

-

Criminal behavior is learned in interactions with other people in the process of communication. This communication is inclusive of both direct and indirect forms of expression.

-

The principal part of the learning of criminal behavior occurs within intimate personal groups. Such learning processes occur with the important and key people in your social life. People acquire criminal tendencies from interactions with these groups.

- When criminal behavior is learned, the learning includes the following:

-

The techniques of committing the crime, which are sometimes very complicated and sometimes very simple

-

The specific direction of motives, drives, rationalizations, and attitudes wherein the learning process involves both instruction on how to commit crimes and why they might be committed

-

The specific direction of motives and drives is learned from the definitions of the legal codes as favorable or unfavorable. That is, they learn the definitions of what is right and wrong. Definitions encompass an individual’s attitude toward the law. Attitudes toward the legality of crimes, deviance, or antisocial behavior can vary.

-

A person becomes a delinquent because of an excess of definitions favorable to violation of the law over definitions unfavorable to violation of the law (i.e., conforming to the law). The balance of exposure to definitions favorable or unfavorable to the law is the primary determinant of whether an individual will engage in crime. If exposed to more definitions that are unfavorable to the law, individuals will be more likely to engage in crime.

-

Differential associations may vary in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity. Not all associations (or interactions) are created equal—how often one interacts with a peer, how much time one spends with a peer, how long someone has known a peer, and how much prestige one attaches to certain peers determines the strength of a particular association.

-

The process of learning criminal behavior by association with criminal and anticriminal patterns involves all of the mechanisms that are involved in any other learning. Learning is a process not specific to crime but to all behavior. Thus, the mechanisms through which we learn how to behave at work or in our families are the same general mechanisms that impact how we learn crime.

-

While criminal behavior is an expression of general needs and values, it is not explained by those general needs and values since noncriminal behavior is an expression of the same needs and values. Behaviors can have the same end goal; however, the means to obtain this goal can vary.

-

EXAMPLE

Selling drugs or working at a retail store may both reflect the need to earn money; thus, we cannot separate delinquent and nondelinquent acts by different goals.

Other factors (e.g., the balance of definitions that one is exposed to) determine whether or not a person engages in a specific behavior (Sutherland & Cressey, 1978, pp. 80–83).

1b. Variations in Social Influence

The primary component of this theory is the role of differential association(s). Individuals have a vast array of social contacts and “intimate personal groups” with whom they interact.

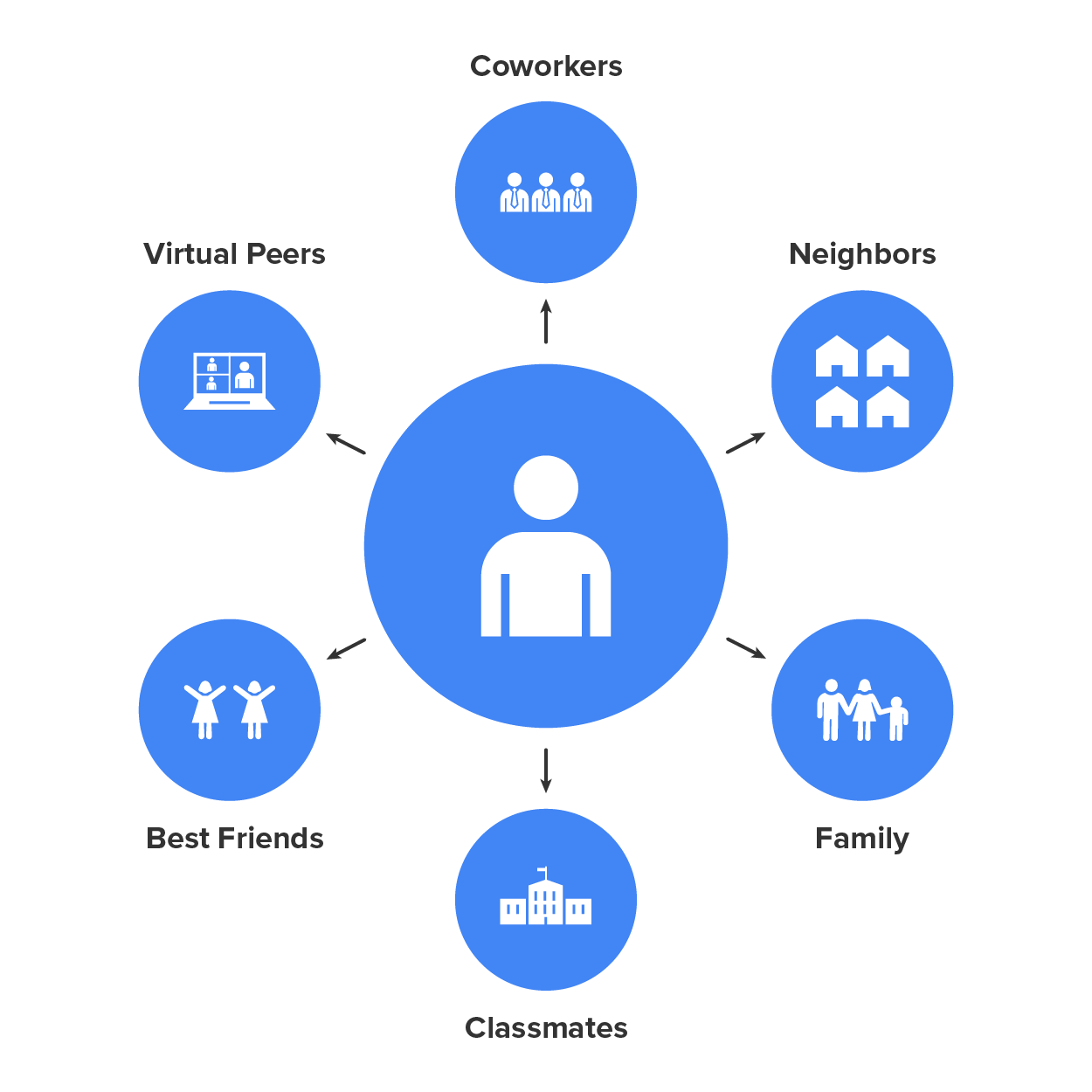

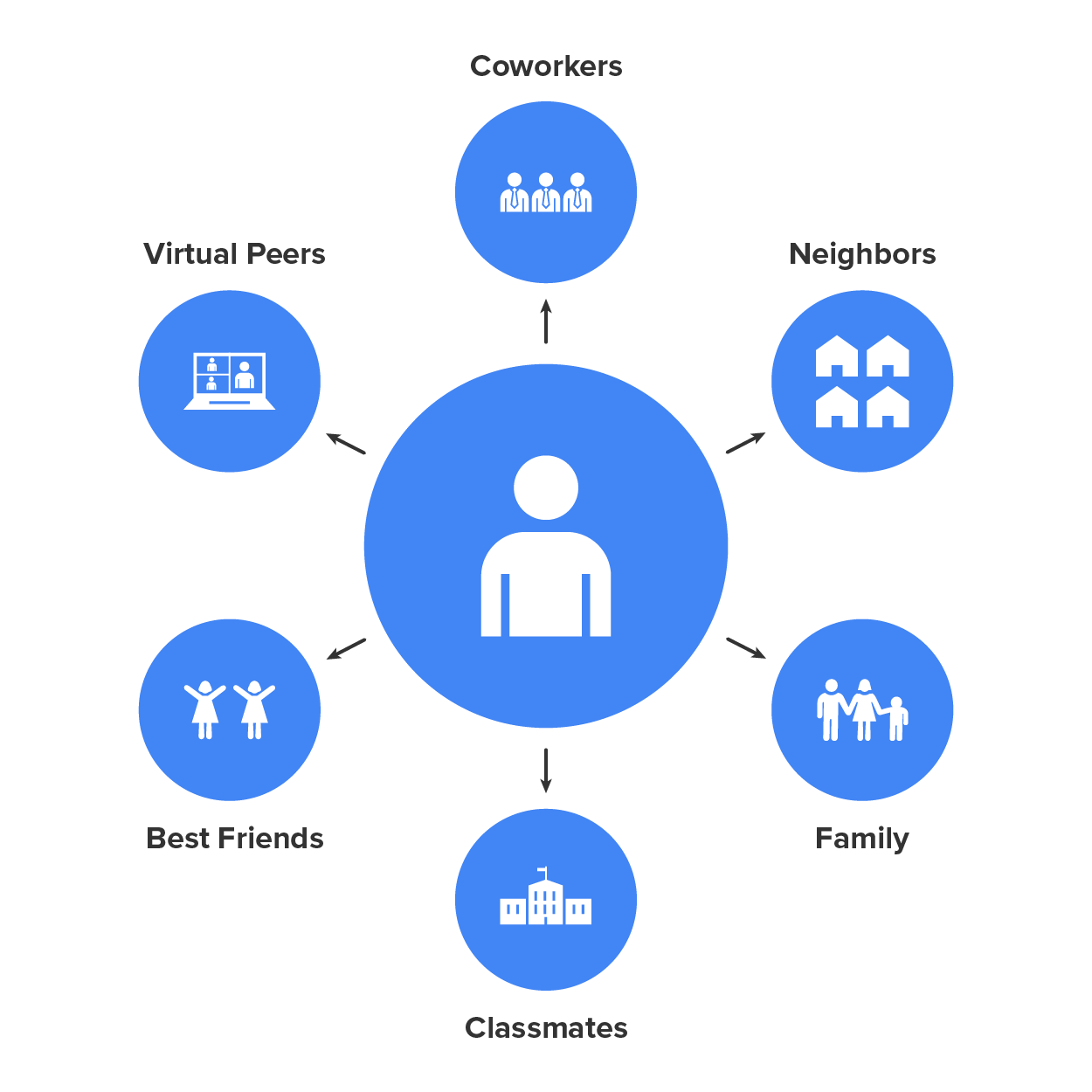

In the image, we can see some examples of the different sources of social influences, including friends, family, classmates, virtual peers, neighbors, and coworkers. They all serve as different sources of social influence, but the extent of their influence depends on the factors that characterize the interactions (e.g., frequency, duration, priority, and intensity). Not all peers or associates have the same level of influence.

-

Consider your own social world—whom do you spend the most time with, trust more, or look to regularly for help?

These individuals comprise your own intimate personal group that facilitates the definitions that you might have regarding deviant or prosocial behavior.

-

EXAMPLE

An individual’s friends who are extremely important to them and whom they have known for multiple years would be anticipated to have a greater degree of influence on that individual’s behavior than a new acquaintance from class or work.

Overall, research demonstrates that affiliation with delinquent peers can explain the initiation, persistence, frequency, type, and cessation of criminal behavior. Association with delinquent peers contributes to criminal behavior partially by shaping one’s attitudes toward the law as either positive or negative.

In this lesson, you learned about differential association theory. This theory was developed by Edwin Sutherland to explain how crime is a learned behavior, similar to how other behaviors are learned. There are nine propositions of differential association theory that state how criminal behavior is learned through others, typically in small intimate groups. People learn the techniques, definitions, and rationalizations of committing crime.

The propositions also teach us that people become delinquent when they have more definitions that favor violating the law than not violating it. Moreover, the theory emphasizes that the frequency and intensity of the interactions with procriminal or anticriminal influences shape an individual’s orientation toward criminal behavior. If a person associates more with those who engage in criminal activities and the interactions are intense, the likelihood of adopting criminal behavior increases.

You also learned that there are variations in social influence. People interact with many different groups, such as friends, family, and coworkers. All of these groups provide a different level of influence on individuals, and the ones whom they have known the longest and interact with more closely will be the ones that they learn the most from. If someone has frequent contact with groups providing favorable definitions and attitudes toward crime, that individual will be more apt to learn those techniques to commit crime.

Differential association theory emphasizes the significance of social influences and the role of learning in shaping an individual’s actions. This theory has been influential in criminology and has contributed to understanding how social environments and interactions play a crucial role in the development of criminal behavior. In the next lesson, we will explore social learning theory, which is a theory that expands upon differential association theory.