Table of Contents |

The artwork that you will be looking at today dates from 1781 to 1823 and focuses geographically on London, England, and Madrid, Spain.

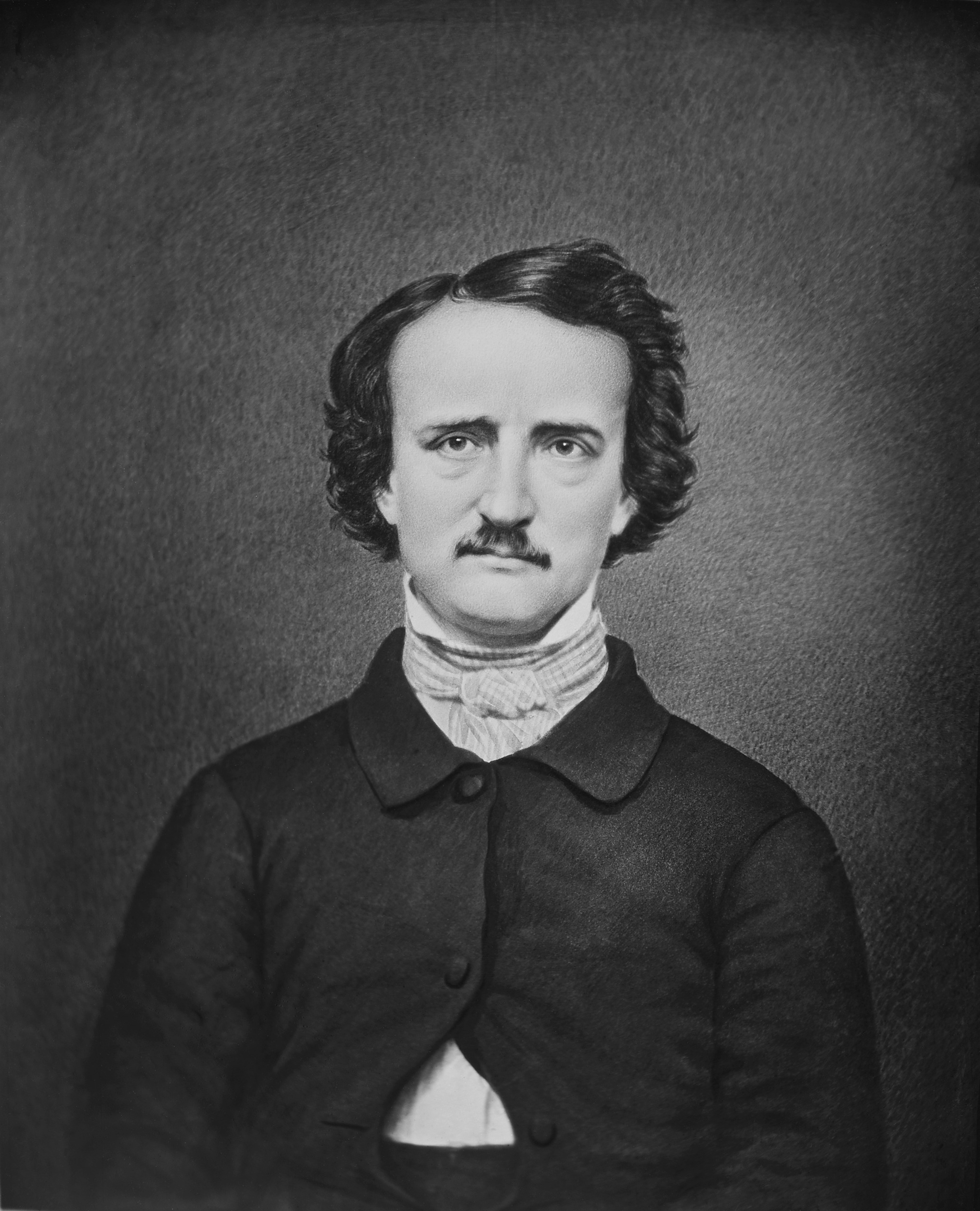

Note, however, that Romanticism wasn’t solely about the visual arts. Dark Romanticism was also a significant literary movement, with authors such as Edgar Allan Poe and Mary Shelley—who wrote Frankenstein—as two of its most important literary figures.

Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe National Archives at College Park, Maryland N.d. (Before 1849) Gelatin Silver Print |

Portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley National Portrait Gallery, London Exhibited in 1840 Oil on canvas |

Gothic—also known as “Gothick”—or Dark Romanticism has the following characteristics:

The enigmatic power of the mind was a crucial concept in the art of Dark Romanticism. The artists and writers of this movement became increasingly fascinated by the Gothic and sublime, delving into metaphysics, the occult, and the realm of nightmares.

The artist Henry Fuseli, although Swiss, spent most of his career in Great Britain.

Henry Fuseli

National Portrait Gallery, London

1778

Oil on canvas

Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare is one of the most iconic and enigmatic works of Dark Romanticism. The painting is renowned for its haunting imagery and psychological complexity, capturing the intersection of the supernatural, the unconscious mind, and human vulnerability.

The Nightmare depicts a young woman stretched across a divan during what is assumed to be a terrible nightmare. The incubus—a mythological demon believed to sit on the chest of sleepers and cause nightmares—symbolizes fear, anxiety, and repressed sexual desires. Its presence on the woman’s chest implies a direct connection to her distress and psychological torment. By anthropomorphizing these terrors in the form of the demon, Fuseli brings the woman’s nightmare to life and forces the viewer to confront these horrors too.

The Nightmare

Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit

1781

Oil on canvas

Behind the young woman, emerging from behind a curtain, is a black horse’s head with luminescent eyes.

The Nightmare captured the public imagination and has remained a powerful and enduring image in art history. It has been referenced and parodied in various forms of media, underscoring its lasting cultural significance.

The painting’s exploration of the human mind and its capacity for terror continues to resonate with contemporary audiences, reflecting the timeless themes of fear and fascination with the unknown.

Many modern interpretations of this painting have suggested that the painting’s overt sexuality served as a precursor to psychologist Sigmund Freud’s study of dream interpretation and the unconscious mind, published in 1900.

In its time, the painting wasn’t well received by Fuseli’s peers, but it has gone on to become one of the works of art that best defines this genre of painting—a masterful depiction of the supernatural and the unconscious mind, blending Gothic and sublime elements to create a haunting and psychologically intricate image.

William Blake, a good friend of Fuseli’s, was an artist, poet, printmaker, and engraver whose work was reflective of his belief in the transcendent nature of the human imagination.

William Blake

National Portrait Gallery, London

1807

Oil on canvas

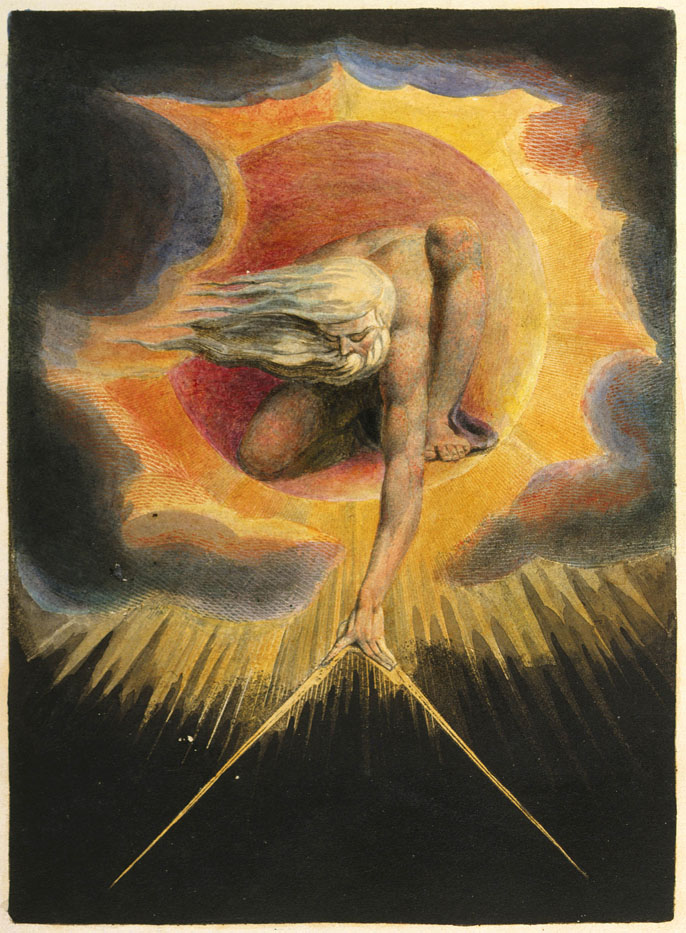

William Blake’s The Ancient of Days is one of his most iconic and significant works. Created in 1794 as a frontispiece for his illuminated book Europe a Prophecy, William Blake developed his own unique interpretations of religion, creating an intricate personal mythology that diverged significantly from traditional Christian doctrine. His mythology features a pantheon of symbolic figures and elaborate narratives that explore the nature of existence, the human condition, and the divine.

In Blake’s mythology, Urizen is a godlike figure embodying law, reason, and order. He represents the rational, controlling aspects of human consciousness that impose structure on the chaotic and infinite potential of the universe.

In The Ancient of Days, Urizen is depicted within a radiant, sunlike disc, symbolizing enlightenment, creation, and divine authority. Urizen uses a large compass, an architect’s tool, which he dips into the inky blackness below. This act of measuring and defining represents his attempt to impose order and rationality on the universe. The compass, a traditional symbol of creation and design, highlights Urizen’s role as a cosmic architect, shaping existence according to his rigid principles.

The painting captures the duality of creation—while Urizen brings order and form, he also imposes limitations, restricting the boundless potential of the universe.

Blake’s portrayal of Urizen’s creation is both awe-inspiring and cautionary, illustrating the power and danger of reason when it becomes too dominant. The image reflects Blake’s belief that an overemphasis on rationality and control can lead to a loss of spiritual insight and imaginative freedom.

Europe a Prophecy: Ancient of Days

British Museum, London

1794

Ink, watercolor, and oil on paper

For Blake, imagination superseded reason and logic. This theme of reason and logic trying to constrain the sublimity of nature is evident in another one of Blake’s works, shown below, in which the nude figure of Isaac Newton is portrayed in a cave, using a similar tool in his attempts to explain the universe mathematically.

Newton’s intense focus on his tools, oblivious to the surrounding sea, symbolizes spiritual blindness. Blake saw this as a metaphor for those who prioritize scientific rationality over spiritual and creative insights.

The painting implies that true wisdom requires a balance between rational thought and imaginative vision—a recurring theme in Blake’s work.

Newton

Tate Britain, London

1804–1805

Monotype with watercolor pigments

The Spanish painter Francisco de Goya is considered by many to be the father of modernist painting. His long and fascinating career comprises a varied collection of artistic styles, media, and subject matter. Goya’s artwork serves as a social barometer of sorts—as a form of his own personal expression and as a reflection of the political and social climate of the time.

Portrait of Francisco de Goya

Museo del Prado, Madrid

1826

Oil on canvas

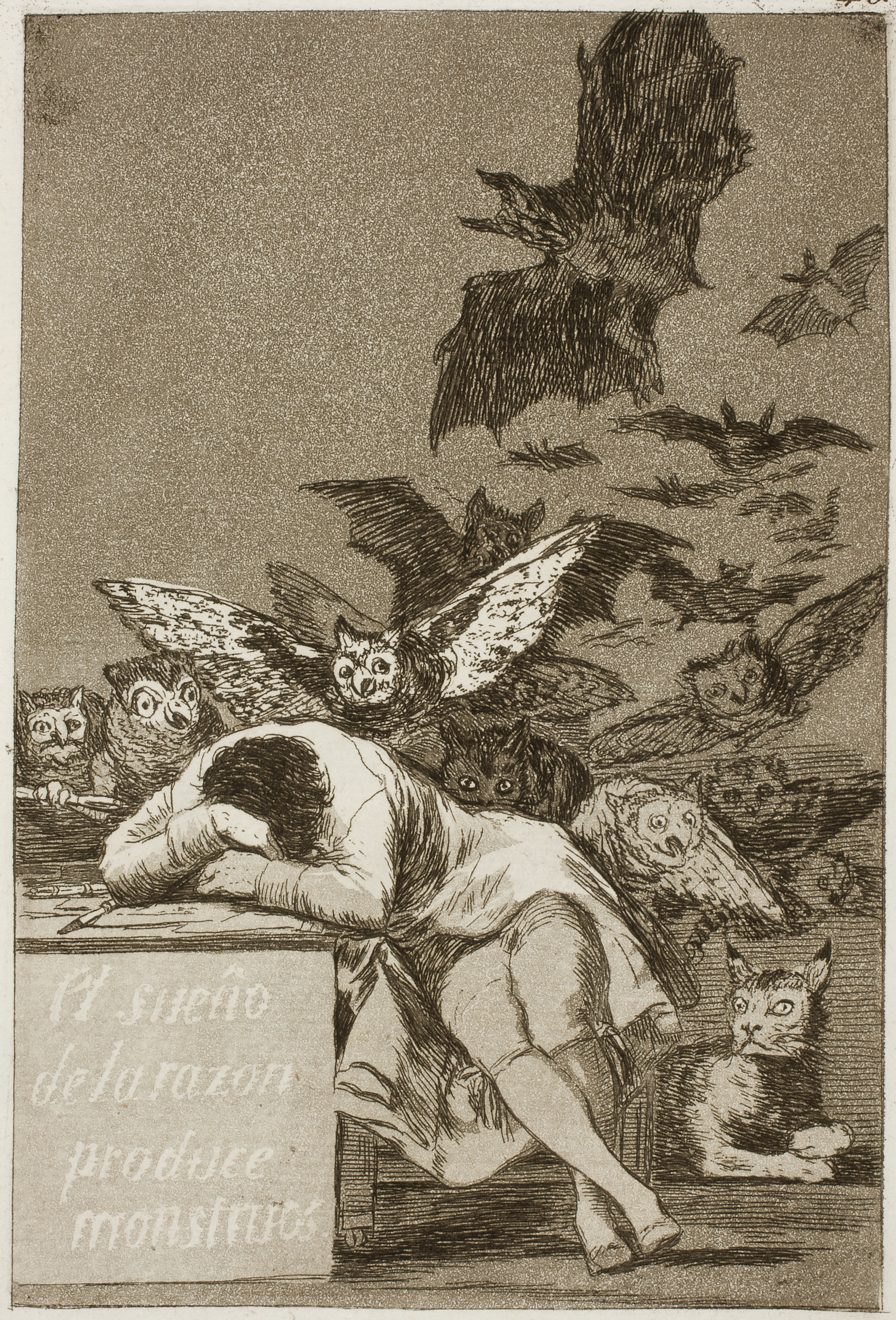

Placing this next example in historical context, the fear of revolution and social upheaval in late-18th-century Spain was very real to King Charles IV, particularly given the political climate in neighboring France. To preempt potential unrest, Charles sought to limit French influence in Spain, especially concerning the availability of literature. It is important to note that France was the epicenter of the Enlightenment during this period, a time marked by a resurgence of human logic and reason. Goya’s print, called The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, is believed to be a work of art directed at the common people—perhaps a warning regarding the dangers of ignoring reason. It depicts a personification of reason, who is asleep, and the resulting release of a nightmarish menagerie of bats, owls, and a cat.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Nightmares

Museo del Prado, Madrid

1799

Etching and aquatint

Several years after The Sleep of Reason Produces Nightmares, Spain was occupied by French forces during one of Napoleon’s many military campaigns. Goya was one of many who welcomed the French, believing that the influx of French culture and a new constitution was beneficial for the people of Spain.

Soon after, however, a rumor spread that the French army was planning to kill the royal family of Spain. The people who rallied and fought against the French to protect the royal family were themselves rounded up and summarily executed by a firing squad. Goya’s iconic painting The Third of May, 1808 both documents and memorializes the Napoleonic Wars, capturing the horror of that day of execution as well as the terrifying moments before a line of French soldiers, rather rigid and mechanical in their posture, fire upon a group of Spanish civilians. Goya’s work serves as a historical document capturing the tragic aftermath of the uprising and the indiscriminate violence inflicted upon the Spanish people.

Goya employs dramatic contrasts of light and shadow to focus a powerful light on the central figure of a condemned man with outstretched arms, resembling a crucifixion. This use of chiaroscuro heightens the emotional intensity of the painting and draws the viewer’s attention to the victims’ suffering.

The composition is asymmetrical, with the French soldiers forming a dark, anonymous mass on the right, contrasting with the individuality and humanity of the Spanish victims on the left. This stark juxtaposition underscores the brutality and dehumanization of the executions.

The Third of May, 1808

Museo del Prado, Madrid

1814

Oil on canvas

The dramatic lighting brings your attention to the central figure in white, his arms extended as if being crucified. You can actually see the inclusion of the stigmata—the wounds suffered by Christ when nailed to the cross—on the palm of his hand.

The Third of May, 1808 is one of the earliest and most powerful anti-war paintings. Goya does not glorify the heroism of battle but instead exposes the grim reality and senseless violence of war. The painting serves as a poignant critique of the horrors of conflict and the suffering of innocent civilians.

By focusing on the victims rather than the glory of military action, Goya challenges traditional representations of war and prompts viewers to reconsider the true nature of armed conflict.

This final example by Goya presents a disturbingly intense depiction of the mythological titan Saturn, known as Cronus in Greek mythology, devouring one of his children.

Saturn Devouring His Son

Museuo del Prado, Madrid

1819–1823

Oil on canvas

Saturn Devouring His Son

Museuo del Prado, Madrid

1636–1638

Oil on canvas

In comparison, Goya’s depiction of Saturn appears depraved as this painting was created during a profoundly dark period in Goya’s life, reflecting his own struggles with madness. He had lost his hearing because of an infection, leaving him feeling isolated and alone. Additionally, his narrow escape from imprisonment by the reestablished Spanish monarchy and the Inquisition exacerbated his bleak outlook.

This artwork features anthropomorphized representations of evil, characteristic of Dark Romanticism, and serves as a not-so-subtle metaphor for Goya’s personal feelings about the Spanish government’s oppressive relationship with its people.

J. M. W. Turner’s painting The Slave Ship explores the sublime through the subject matter. Insurance companies at the time would only compensate owners for slaves lost at sea, not slaves that died of natural causes. To avoid financial loss, the captain of the slave ship ordered all the sick and dying to be tossed overboard.

The Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon Coming On)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

1799

Oil on canvas

Notice how the sublime beauty of the boiling sea and the fiery sky—as well as the ship heading into the approaching typhoon—nearly overshadow the drama happening in the foreground. If you look at the close-up below, you can see the arms and hands of slaves in shackles as they are being pulled underwater.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY IAN MCCONNELL AND TAMORA KOWALSKI FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.