Table of Contents |

The artwork in this lesson spans from 1917 to 1919 and is geographically located in Zurich, Switzerland. Switzerland is where the Dada movement originated in 1916.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Dada is that it was less of an artistic style and more of an artistic philosophy. Rather than adhering to a specific aesthetic, Dada was a reactionary movement that emerged in response to the horrors of World War I, embodying a strong anti-war sentiment. Artists within the Dada movement used unconventional techniques such as collage, assemblage, photomontage, and readymades to create works that were deliberately shocking and provocative, designed to jolt their audience out of complacency.

A key objective of Dada artists was to challenge the status quo and make their audience acutely aware of the absurdity and contradictions of their societal positions. The bourgeoisie was a frequent target of Dadaist critique. Dada artists vehemently opposed bourgeois values, which they believed were complicit in the apathy and moral decay that led to the catastrophic violence of war. Through their art, they sought to expose the bourgeoisie’s willingness to maintain their way of life, even at the cost of engaging in destructive conflict, rather than embracing meaningful change.

There were also many authors and poets within the Dada movement. In fact, the Dada movement’s impetus is often credited to the poet Hugo Ball. After moving to the war-neutral country of Switzerland, Ball established a cabaret called the Cabaret Voltaire. Many other artists who fled to Switzerland in opposition to the war and to avoid being drafted congregated at the Cabaret Voltaire.

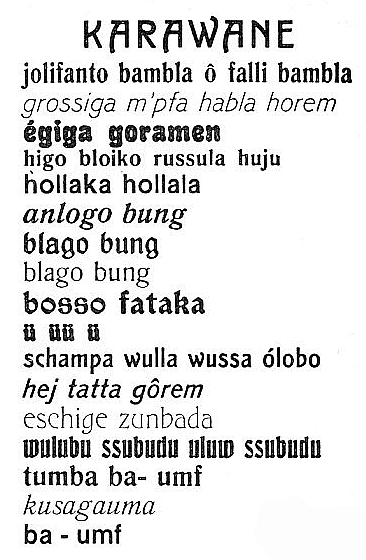

Hugo Ball’s reading of his poem Karawane, shown below, sparked the Dada movement.

Karawane

1917

Poem reading at the Cabaret Voltaire, Zürich

He performed a reading dressed in a cardboard costume featuring lobster-like claws, a witch doctor’s hat, and a cape. The poem he recited was a jumble of nonsensical sounds, which some believe inspired the name “Dada,” a term resembling baby babble or the first sounds an infant makes.

Dada artists believed that art should be “newborn,” breaking away from the traditions of the past and challenging the established trajectory of art. They argued that society’s values were fundamentally flawed, as evidenced by the descent into World War I. As a result, art had to confront the brutal realities of war and address the deep moral and ethical dilemmas it created.

In reaction to the unimaginable death toll and the perceived senseless waste of human life in the trenches, Dada artists like Jean Arp embraced the aesthetic of refuse. They used small scraps of paper and discarded materials in their collage and assemblage art, turning what was often seen as trash into powerful artistic statements.

Arp’s Collage Arranged According to the Laws of Chance is an example of this aesthetic exploration.

View Collage Arranged According to the Laws of Chance.

View Collage Arranged According to the Laws of Chance.

For artists like Jean Arp, a cofounder of the Dada movement, embracing randomness was a deliberate strategy to strip away the personal control and intentionality that had dominated art up until that point. By allowing chance to dictate the creation process, Arp and his fellow Dadaists sought to challenge the traditional notions of artistic authorship and meaning, making art less about individual expression and more about the unpredictable forces of the world.

This approach not only defied conventional expectations but also laid the groundwork for future artists. Jackson Pollock, for instance, explored similar themes in his action paintings, where the physical act of painting—letting paint drip and splatter spontaneously—echoed the Dadaist embrace of randomness. In this way, Arp’s pioneering work with chance influenced the trajectory of modern art, inspiring subsequent movements that further pushed the boundaries of artistic creation.

Dada eventually spread to Berlin, Germany, where artists such as Hannah Höch, George Grosz, and John Heartfield used photomontage and other techniques to create works of art that function as political satire.

This next image of Höch’s artwork is an example of political satire.

View Cut With the Dada Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany.

View Cut With the Dada Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany.

This artwork also claims the title for the longest name we’ve encountered in all our art history lessons so far. In this work, Hannah Höch combines images and text from newspapers and other media to craft a powerful critique of the Weimar Republic, which governed Germany at the time and was later supplanted by the fascist regime of the National Socialists, or Nazis. Höch’s imagery features masculinized depictions of women symbolically cutting through figures representing the Weimar Republic. Through this visual metaphor, she not only challenges the political structures of her time but also addresses the issues of gender, power, and the roles imposed on women in a rapidly changing society.

Marcel Duchamp created one of the most controversial examples of modern art with his Fountain, an example of “readymade” art and, of all things, a urinal. Rather than making a sculpture with his own skills, Duchamps purchased this urinal at a New York City hardware store in 1917.

Fountain

Lost or destroyed

Photographed by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946)

1917

Porcelain and enamel paint

You may have seen Duchamp’s work before, and not just in the public restroom. His readymade of a Mona Lisa postcard with a mustache has become iconic. But it’s important to look beyond the obvious and question yourself about what he is trying to say.

View L.H.O.O.Q..

View L.H.O.O.Q..

There are numerous interpretations of Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., each offering a different perspective on its significance. One common interpretation is that Duchamp was engaging in a commentary on the concept of readymades—objects that are transformed into art simply by the artist’s selection. By taking an iconic image like the Mona Lisa and adding a mustache and goatee, Duchamp was not only challenging the sanctity of traditional art but also questioning the role of artistic skill and craft. Duchamp was also referring to an obscene sexual phrase as L.H.O.O.Q., when said in French, means much more than a chain of letters. His defacement of such a revered masterpiece serves as a critique of the art world’s obsession with originality, authorship, and the veneration of certain works as untouchable.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY IAN MCCONNELL AND TAMORA KOWALSKI FOR SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.