Table of Contents |

Childbirth is a broad term that encompasses different events that occur throughout labor and delivery. Some describe childbirth as beautiful, a miracle, and a rite of passage. Others may think of pain, fear, and discomfort. Labor and delivery is not an easy feat!

Culture plays a very important role in pregnancy and childbirth. There are similarities and differences in childbirth practices across cultures. This lesson does not cover all cultures throughout the world. Rather, it provides a glimpse into the topic with examples. Regardless of culture, behaviors and practices during pregnancy and childbirth influence postpartum behaviors. For these reasons pregnancy and childbirth are inextricably linked.

We know that cultures, to some extent, are defined by their geographical location. Therefore, we can expect differences and evolving cultural practices as they relate to childbirth. This is supported by research looking at mothers in seven nations (Chalmers, 2012):

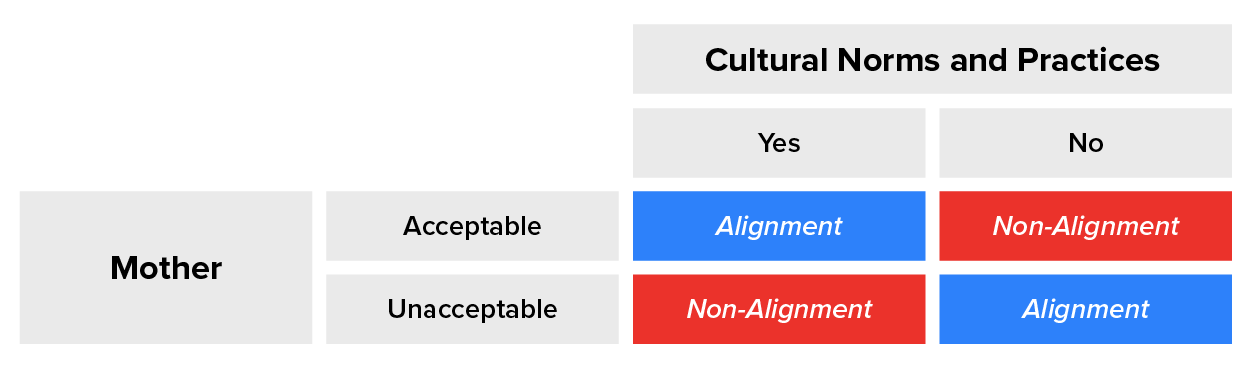

Whether or not a culture accepts these forms of childbirth methods and a mother’s perceptions of these methods interact to form the matrix highlighted below.

In the table above, cultural practices and/or norms towards pregnancy and childbirth are categorized across the top. Along the left side of the table the mother’s perceptions or willingness to utilize those methods are categorized. When there is complete alignment between a mother and the cultural norms there is no discrepancy. Both agree or both disagree. In this case we assume that there is little to no problem. However, this is not always the case. In some instances, an important issue may arise in which the mother and the culture do not agree on a practice even though from a medical perspective, the practice can be life-saving for mother and/or the baby.

EXAMPLE

Women in Zambia are expected to not cry and shout during childbirth, otherwise the baby could die.A similar situation arises when both mother and culture agree on a practice but it is counterintuitive and may do more harm than good. In other words, something is being practiced but rationally and/or through evidence we know it should not be done because it can potentially harm a mother and her baby. When this happens, cultural practices should evolve, to a certain degree, to align with best care practices so that the health of mother, baby, and society are not further compromised.

EXAMPLE

Zambian women utilize different methods to speed up labor (e.g., placing a finger or cooking stick in mother’s mouth so she gags which results in opening the uterus) or removing the placenta by placing the hand into the vagina (Maimbolwa, Yamba, Diwan, & Ransjö-Arvidson, 2003).We cannot definitively say that one type of disconnect between a mother’s perspective and cultural perspective—whether they agree or disagree on a practice—causes more harm than the other. As we can see from the examples above, it depends on the type of practice and individual-level factors.

Let’s now consider the discrepancy occurring where either the mother finds a childbirth method appealing or necessary, and the culture goes against it, or vice versa. We assume that this conflict also significantly impacts a mother’s and baby’s health on many levels.

EXAMPLE

Asian-Indian culture is rooted in many traditions that impact a pregnant woman and her baby. These range from forbidden foods (e.g., papaya) to a required at-home rest period postpartum with restrictions on who has access to mother and baby (Cousik & Hickey, 2016; Goyal, 2016; Grewal et al., 2008; Naser et al., 2012; Wells & Dietsch, 2014). To highlight this further, a mother and her newborn are not allowed to have outside visitors and cannot go outside of the house for the first forty-days. From a cultural perspective, this is to protect the mother and baby from negative influences (or the ‘evil eye’ as it is sometimes culturally referred to). But, let’s think about it from a mother’s point of view. She has just given birth to her baby and is not allowed outside her house and cannot invite many people over who may be able to support her during this sensitive period. A mother is overcome with emotions that she may need the support of her family, friends, relatives, and neighbors but is not allowed to do so. She may want to take a breath of fresh air and expose her baby to nature and its beauty, but again, it is highly frowned upon depending on the family and their belief systems.For immigrant Asian-Indians, there is a clash between the U.S. and Indian cultures when it comes to what a pregnant woman can and cannot do (George, Shin, & Habermann, 2022). Indian mothers are expected to rest, limit strenuous activity, and only do light work if necessary. This is in comparison to mothers in the U.S. who are encouraged to remain active and go about their daily activities as much as possible.

When this conflict arises, it places the mother in a precarious position - should she do what she feels is best or should she follow her root culture even if she is uncomfortable and disagrees with it? If she goes against the dominant culture’s practices, then she might be socially ostracized by the other culture. We can ask many questions around this scenario but in the end, the mother faces the consequences of her actions. This is not to say that every Asian-Indian immigrant mother shares the same experiences.

IN CONTEXT

Tibetan culture also offers us an exceptional example of how culture impacts pregnancy and childbirth (Craig, 2009). Sienna R. Craig is an anthropologist who immerses herself in Tibetan culture and ways of living. She provides an account of a mother and illustrates her in-depth experiences while also analyzing this in the larger global health context. In Craig’s paper, a woman who goes by the pseudonym Lhakpa Droma describes her four pregnancies of which only two children survived. Lhakpa expresses her inner conflict because she has to work, otherwise she will be perceived weak, and a weak mother cannot effectively deliver a baby. She delivered her youngest child in a corner of her home with only her husband at her side. She used a knife to cut her baby’s umbilical cord and washed the knife afterwards. Why afterwards? Because childbirth blood is considered defiled according to Tibetan culture, therefore instead of sanitizing the knife beforehand, it is sanitized afterwards.

Lhakpa’s experiences are rooted in how Tibetan culture views pregnancy and childbirth. A mother’s perception of things happening around her and with her are key to her well-being. Throughout her discourse with the anthropologist, Lhakpa appears uncomfortable to discuss details involving pregnancy and how she told her husband about their baby in her third or fourth month. In Tibetan culture, it is common to avoid telling others that you are pregnant because mothers who have difficulty conceiving may become jealous or harbor negative feelings. However, from a public health and medical lens, not divulging you are pregnant indicates that you do not have access to resources and knowledge to help you throughout your pregnancy, especially in the early stages. It may also indicate that you might not exert caution when necessary in your daily activities.

Lhakpa had a home birth and was hesitant about delivering at a clinic or hospital. While more Westernized nations and industrialized cities have birthing centers and hospitals, access to such facilities is problematic in rural areas. Pregnant women living in rural, hilly, or mountainous areas must consider transportation and financial issues if they need to deliver outside of the home. This is coupled with the fact that in Tibetan culture, it is believed that the presence of strangers can impact the baby’s soul.

Culturally, Tibet is not known for having midwives and formalized birth attendants since female relatives are usually with the mother during childbirth or the mother delivers by herself with no one to help her (Craig, 2009). An at-home birth can occur anywhere, including in an animal pen. Worldwide, when communities do not have access to formalized healthcare settings and personnel, community health workers and midwives are accessible. They can provide the mother with knowledge, tools, and other resources to enhance her pregnancy experience and improve maternal and baby outcomes. While Tibetans have a traditional medical practitioner called an Amchi, this individual is not typically present during childbirth, especially if this individual is male. Therefore, adding on to lack of facilities and personnel to help deliver a baby, there is also a gender preference for who can help during labor and delivery.

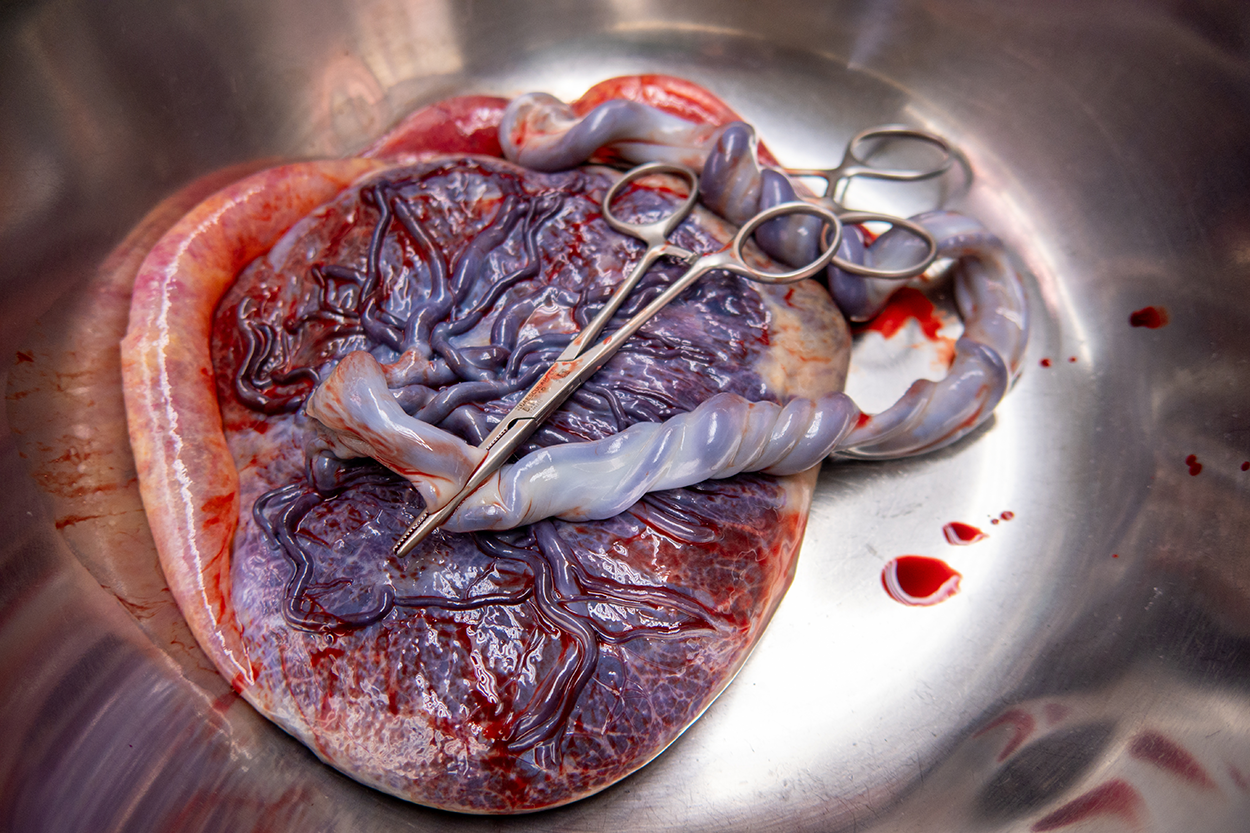

The placenta often plays an important role in various cultures, with many societies conducting rituals regarding its disposal. In the Western world, the placenta is most often incinerated.

In some cultures the placenta is buried for various reasons.

In some cultures, the placenta is eaten, a practice known as placentophagy. In some eastern cultures, such as China, the dried placenta (ziheche, literally “purple river car”) is thought to be a healthful restorative and is sometimes used in preparations of traditional Chinese medicine and various health products. The practice of human placentophagy has become a more recent trend in western cultures and is not without controversy. Some cultures have alternative uses for placenta that include the manufacturing of cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and food.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL WAS AUTHORED BY SOPHIA LEARNING. PLEASE SEE OUR TERMS OF USE.

REFERENCES

Chalmers, B. (2012). Childbirth across cultures: research and practice. Birth, 39(4), 276-280.

Cousik R., Hickey M. (2016). Pregnancy and childbirth practices among immigrant women from India: “Have a healthy baby.” The Qualitative Report, 21(4), 727–743. Retrieved January 12, 2023 from nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol21/iss4/9

Craig, S. R. (2009). Pregnancy and childbirth in Tibet: Knowledge, perspectives, and practices. Childbirth Across Cultures, 145-160.

George, G. M., Shin, J. Y., & Habermann, B. (2022). Immigrant Asian Indian Mothers’ Experiences With Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Infant Care in the United States. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 33(3), 373-380.

Goyal D. (2016). Perinatal practices & traditions among Asian Indian women. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/child Nursing, 41(2), 90–97. Retrieved January 12, 2023 from doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000000222

Grewal S. K., Bhagat R., Balneaves L. G. (2008). Perinatal beliefs and practices of immigrant Punjabi women living in Canada. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 37(3), 290–300. Retrieved January 12, 2023 from doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00234.x

Lazzara, J. (n.d.). Chapter 3: Birth and the newborn child. Lifespan Development. Retrieved January 12, 2023, from open.maricopa.edu/devpsych/chapter/chapter-3-birth-and-the-newborn-child/

Maimbolwa, M. C., Yamba, B., Diwan, V., & Ransjö‐Arvidson, A. B. (2003). Cultural childbirth practices and beliefs in Zambia. Journal of advanced nursing, 43(3), 263-274.Cousik R., Hickey M. (2016). Pregnancy and childbirth practices among immigrant women from India: “Have a healthy baby.” The Qualitative Report, 21(4), 727–743. Retrieved January 12, 2023 from nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol21/iss4/9

Naser E., Mackey S., Arthur D., Klainin-Yobas P., Chen H., Creedy D. K. (2012). An exploratory study of traditional birthing practices of Chinese, Malay and Indian women in Singapore. Midwifery, 28(6), Article e871. Retrieved January 12, 2023 from doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2011.10.003

Wells Y. O., Dietsch E. (2014). Childbearing traditions of Indian women at home and abroad: An integrative literature review. Women and Birth, 27(4), e1–e6. Retrieved January 12, 2023 from doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2014.08.006