Table of Contents |

The theories presented in this section focus on the importance of human needs. A common thread through all of them is that people have a variety of needs. A need is a human condition that becomes “energized” when people feel deficient in some respect.

EXAMPLE

When we are hungry, our need for food has been energized.Two features of needs are key to understanding motivation. First, when a need has been energized, we are motivated to satisfy it. We strive to make the need disappear. Hedonism, one of the first motivation theories, assumes that people are motivated to satisfy mainly their own needs (seek pleasure, avoid pain). Long since displaced by more refined theories, hedonism clarifies the idea that needs provide direction for motivation. Second, once we have satisfied a need, it ceases to motivate us. When we’ve eaten to satiation, we are no longer motivated to eat. Other needs take over and we endeavor to satisfy them. A manifest need is whatever need is motivating us at a given time. Manifest needs dominate our other needs.

Instincts are our natural, fundamental needs, basic to our survival. Our needs for food and water are instinctive. Many needs are learned. We are not born with a high (or low) need for achievement—we learn to need success (or failure). The distinction between instinctive and learned needs sometimes blurs; for example, is our need to socialize with other people instinctive or learned?

David C. McClelland and his associates (especially John W. Atkinson) studied three needs in depth: the need for achievement, the need for affiliation, and the need for power (often abbreviated, in turn, as nAch, nAff, and nPow) (Akkinson & McClelland, 1948). McClelland believes that these three needs are learned, primarily in childhood. But he also believes that each need can be taught, especially nAch. McClelland’s research is important because much of current thinking about organizational behavior is based on it.

The need for achievement (nAch) is how much people are motivated to excel at the tasks they are performing, especially tasks that are difficult. Of the three needs studied by McClelland, nAch has the greatest impact. The need for achievement varies in intensity across individuals. This makes nAch a personality trait as well as a statement about motivation. When nAch is being expressed, making it a manifest need, people try hard to succeed at whatever task they’re doing. We say these people have a high achievement motive. A motive is a source of motivation; it is the need that a person is attempting to satisfy. Achievement needs become manifest when individuals experience certain types of situations.

To better understand the nAch motive, it’s helpful to describe high-nAch people. You probably know a few of them. They’re constantly trying to accomplish something. One of your authors has a father-in-law who would much rather spend his weekends digging holes (for various home projects) than going fishing. Why? Because when he digs a hole, he gets results. In contrast, he can exert a lot of effort and still not catch a fish. A lot of fishing, no fish, and no results equal failure!

McClelland describes three major characteristics of high-nAch people:

Many organizations manage the achievement needs of their employees poorly. A common perception about people who perform unskilled jobs is that they are unmotivated and content doing what they are doing. But, if they have achievement needs, the job itself creates little motivation to perform. It is too easy. There are not enough workers who feel personal satisfaction for having the cleanest floors in a building. Designing jobs that are neither too challenging nor too boring is key to managing motivation. Job enrichment is one effective strategy; this frequently entails training and rotating employees through different jobs, or adding new challenges.

This need is the second of McClelland’s learned needs. The need for affiliation (nAff) reflects a desire to establish and maintain warm and friendly relationships with other people. As with nAch, nAff varies in intensity across individuals. As you would expect, high-nAff people are very sociable. They’re more likely to go bowling with friends after work than to go home and watch television. Other people have lower affiliation needs. This doesn’t mean that they avoid other people, or that they dislike others. They simply don’t exert as much effort in this area as high-nAff people do.

The nAff has important implications for organizational behavior. High-nAff people like to be around other people, including other people at work. As a result, they perform better in jobs that require teamwork. Maintaining good relationships with their coworkers is important to them, so they go to great lengths to make the work group succeed because they fear rejection. So, high-nAff employees will be especially motivated to perform well if others depend on them. In contrast, if high-nAff people perform jobs in isolation from other people, they will be less motivated to perform well. Performing well on this job won’t satisfy their need to be around other people.

Effective managers carefully assess the degree to which people have high or low nAff. Employees high in nAff should be placed in jobs that require or allow interactions with other employees. Jobs that are best performed alone are more appropriate for low-nAff employees, who are less likely to be frustrated.

The third of McClelland’s learned needs, the need for power (nPow), reflects a motivation to influence and be responsible for other people. An employee who is often talkative, gives orders, and argues a lot is motivated by the need for power over others.

Employees with high nPow can be beneficial to organizations. High-nPow people do have effective employee behaviors, but at times they’re disruptive. A high-nPow person may try to convince others to do things that are detrimental to the organization. So, when is this need good, and when is it bad? Again, there are no easy answers. McClelland calls this the “two faces of power" (McClelland, 1970). A personal power seeker endeavors to control others mostly for the sake of dominating them. They want others to respond to their wishes whether or not it is good for the organization. They “build empires,” and they protect them.

McClelland’s other power seeker is the social power seeker. A high social power seeker satisfies needs for power by influencing others, like the personal power seeker. They differ in that they feel best when they have influenced a work group to achieve the group’s goals, and not some personal agenda. High social power seekers are concerned with goals that a work group has set for itself, and they are motivated to influence others to achieve the goal. This need is oriented toward fulfilling responsibilities to the employer, not to the self.

McClelland has argued that the high need for social power is the most important motivator for successful managers. Successful managers tend to be high in this type of nPow. High need for achievement can also be important, but it sometimes results in too much concern for personal success and not enough for the employer’s success. The need for affiliation contributes to managerial success only in those situations where the maintenance of warm group relations is as important as getting others to work toward group goals.

The implication of McClelland’s research is that organizations should try to place people with high needs for social power in managerial jobs. It is critical, however, that those managerial jobs allow the employee to satisfy the nPow through social power acquisition. Otherwise, a manager high in nPow may satisfy this need through acquisition of personal power, to the detriment of the organization.

Any discussion of needs that motivate performance would be incomplete without considering Abraham Maslow (Maslow, 1943). Thousands of managers in the 1960s were exposed to Maslow’s theory through the popular writings of Douglas McGregor (McGregor, 1960). Today, many of them still talk about employee motivation in terms of Maslow’s theory.

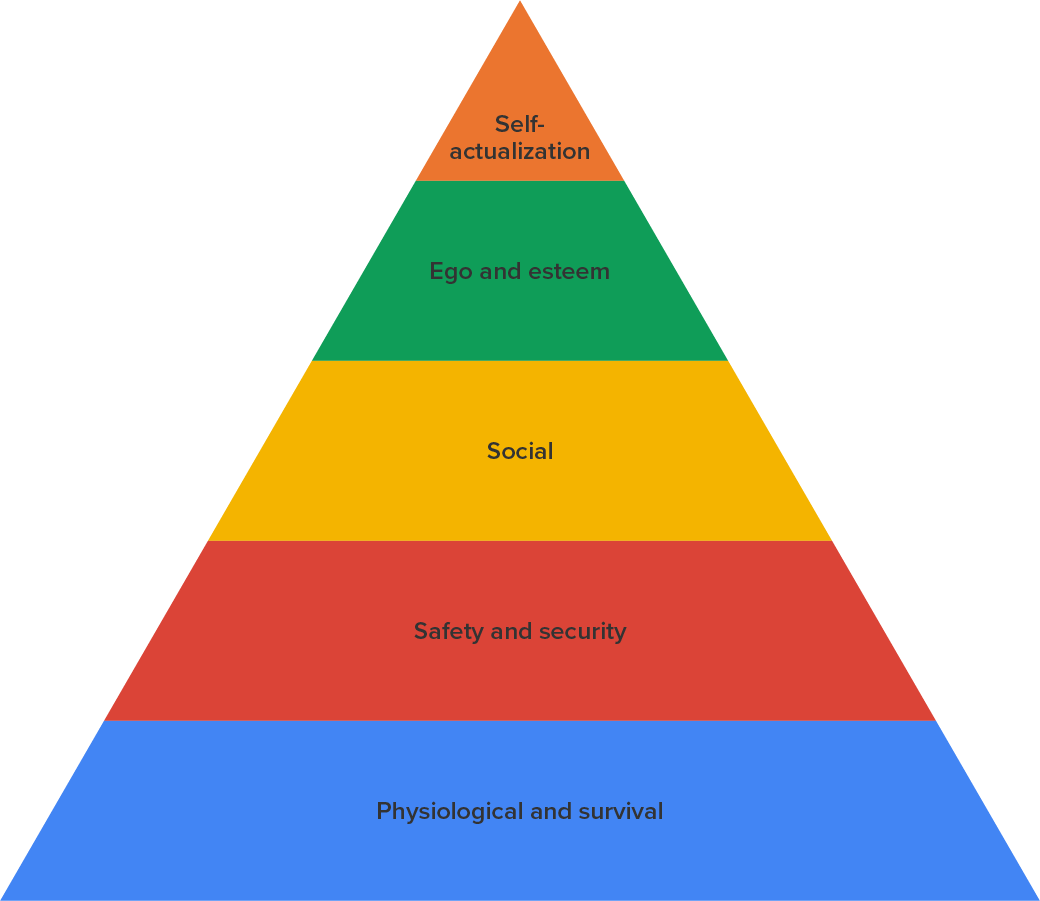

Maslow was a psychologist who, based on his early research with primates (monkeys), observations of patients, and discussions with employees in organizations, theorized that human needs are arranged hierarchically. That is, before one type of need can manifest itself, other needs must be satisfied.

EXAMPLE

Our need for water takes precedence over our need for social interaction (this is also called prepotency). We will always satisfy our need for water before we satisfy our social needs; water needs have prepotency over social needs.Maslow’s theory differs from others that preceded it because of this hierarchical, prepotency concept.

Maslow went on to propose five basic types of human needs. This is in contrast to the thousands of needs that earlier researchers had identified. Maslow condensed human needs into a manageable set. Those five human needs, in the order of prepotency in which they direct human behavior, are:

An overriding principle in this theory is that a person’s attention (direction) and energy (intensity) will focus on satisfying the lowest-level need that is not currently satisfied. Needs can also be satisfied at some point but become active (dissatisfied) again. Needs must be “maintained” (we must continue to eat occasionally). According to Maslow, when lower-level needs are reactivated, we once again concentrate on that need. That is, we lose interest in the higher-level needs when lower-order needs are energized.

The implications of Maslow’s theory for organizational behavior are as much conceptual as they are practical. The theory posits that to maximize employee motivation, employers must try to guide workers to the upper parts of the hierarchy. That means that the employer should help employees satisfy lower-order needs like safety and security and social needs. Once satisfied, employees will be motivated to build esteem and respect through their work achievements. The diagram shows how Maslow’s theory relates to factors that organizations can influence. For example, by providing adequate pay, safe working conditions, and cohesive work groups, employers help employees satisfy their lower-order needs. Once satisfied, challenging jobs, additional responsibilities, and prestigious job titles can help employees satisfy higher-order esteem needs.

Maslow’s theory is still popular among practicing managers. Organizational behavior researchers, however, are not as enamored with it because research results don’t support Maslow’s hierarchical notion. Apparently, people don’t go through the five levels in a fixed fashion. On the other hand, there is some evidence that people satisfy the lower-order needs before they attempt to satisfy higher-order needs. Refinements of Maslow’s theory in recent years reflect this more limited hierarchy (Alderfer, 1972).

Clayton Alderfer observed that very few attempts had been made to test Maslow’s full theory. Further, the evidence accumulated provided only partial support. During the process of refining and extending Maslow’s theory, Alderfer provided another need-based theory and a somewhat more useful perspective on motivation (Hall & Nougaim, 1968). Alderfer’s ERG theory compresses Maslow’s five need categories into three: existence, relatedness, and growth (Alderfer, 1972). In addition, ERG theory details the dynamics of an individual’s movement between the need categories in a somewhat more detailed fashion than typically characterizes interpretations of Maslow’s work.

As shown in the diagram below, the ERG model addresses the same needs as those identified in Maslow’s work:

| Growth Opportunities | Relatedness Opportunities | Existence Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Four components—satisfaction progression, frustration, frustration regression, and aspiration—are key to understanding Alderfer’s ERG theory. The first of these, satisfaction progression, is in basic agreement with Maslow’s process of moving through the needs. As we increasingly satisfy our existence needs, we direct energy toward relatedness needs. As these needs are satisfied, our growth needs become more active. The second component, frustration, occurs when we attempt but fail to satisfy a particular need. The resulting frustration may make satisfying the unmet need even more important to us—unless we repeatedly fail to satisfy that need. In this case, Alderfer’s third component, frustration regression, can cause us to shift our attention to a previously satisfied, more concrete, and verifiable need. Lastly, the aspiration component of the ERG model notes that, by its very nature, growth is intrinsically satisfying. The more we grow, the more we want to grow. Therefore, the more we satisfy our growth needs, the more important it becomes and the more strongly we are motivated to satisfy it.

Alderfer’s model is potentially more useful than Maslow’s in that it doesn’t create false motivational categories.

EXAMPLE

It is difficult for researchers to ascertain when interaction with others satisfies our need for acceptance and when it satisfies our need for recognition.ERG also focuses attention explicitly on movement through the set of needs in both directions. Further, evidence in support of the three need categories and their order tends to be stronger than evidence for Maslow’s five need categories and their relative order.

Clearly one of the most influential motivation theories throughout the 1950s and 1960s was Frederick Herzberg’s motivator-hygiene theory. This theory is a further refinement of Maslow’s theory. Herzberg argued that there are two sets of needs instead of the five sets theorized by Maslow. He called the first set “motivators” (or growth needs). Motivators, which relate to the jobs we perform and our ability to feel a sense of achievement as a result of performing them, are rooted in our need to experience growth and self-actualization. The second set of needs he termed “hygienes.” Hygienes relate to the work environment and are based on the basic human need to “avoid pain.” According to Herzberg, growth needs motivate us to perform well and, when these needs are met, lead to the experience of satisfaction. Hygiene needs, on the other hand, must be met to avoid dissatisfaction (but do not necessarily provide satisfaction or motivation) (Herzberg et al., 1959).

Hygiene factors are not directly related to the work itself (job content). Rather, hygienes refer to job context factors (pay, working conditions, supervision, and security). Herzberg also refers to these factors as “dissatisfiers” because they are frequently associated with dissatisfied employees. These factors are so frequently associated with dissatisfaction that Herzberg claims they never really provide satisfaction. When they’re present in sufficient quantities, we avoid dissatisfaction, but they do not contribute to satisfaction. Furthermore, since meeting these needs does not provide satisfaction, Herzberg concludes that they do not motivate workers.

Motivator factors involve our long-term need to pursue psychological growth (much like Maslow’s esteem and self-actualization needs). Motivators relate to job content. Job content is what we actually do when we perform our job duties. Herzberg considered job duties that lead to feelings of achievement and recognition to be motivators. He refers to these factors as “satisfiers” to reflect their ability to provide satisfying experiences. When these needs are met, we experience satisfaction. Because meeting these needs provides satisfaction, they motivate workers. More specifically, Herzberg believes these motivators lead to high performance (achievement), and the high performance itself leads to satisfaction.

The unique feature of Herzberg’s theory is that job conditions that prevent dissatisfaction do not cause satisfaction. Satisfaction and dissatisfaction are on different “scales” in his view. Hygienes can cause dissatisfaction if they are not present in sufficient levels. Thus, an employee can be dissatisfied with low pay. But paying him or her more will not cause long-term satisfaction unless motivators are present. Good pay by itself will only make the employee neutral toward work; to attain satisfaction, employees need challenging job duties that result in a sense of achievement. Employees can be dissatisfied, neutral, or satisfied with their jobs, depending on their levels of hygienes and motivators. Herzberg’s theory even allows for the possibility that an employee can be satisfied and dissatisfied at the same time—the “I love my job but I hate the pay” situation!

Herzberg’s theory has made lasting contributions to organizational research and managerial practice. Researchers have used it to identify the wide range of factors that influence worker reactions. Previously, most organizations attended primarily to hygiene factors. Because of Herzberg’s work, organizations today realize the potential of motivators. Job enrichment programs are among the many direct results of his research.

Herzberg’s work suggests a two-stage process for managing employee motivation and satisfaction. First, managers should address the hygiene factors. Intense forms of dissatisfaction distract employees from important work-related activities and tend to be demotivating (Dunham et al., 1983). Thus, managers should make sure that such basic needs as adequate pay, safe and clean working conditions, and opportunities for social interaction are met. They should then address the much more powerful motivator needs, in which workers experience recognition, responsibility, achievement, and growth. If motivator needs are ignored, neither long-term satisfaction nor high motivation is likely. When motivator needs are met, however, employees feel satisfied and are motivated to perform well.

One major implication of Herzberg’s motivator-hygiene theory is the somewhat counterintuitive idea that managers should focus more on motivators than on hygienes. After all, doesn’t everyone want to be paid well? Organizations have held this out as a chief motivator for decades! Why might concentrating on motivators give better results? To answer this question, we must examine types of motivation. Organizational behavior researchers often classify motivation in terms of what stimulates it. In the case of extrinsic motivation, we endeavor to acquire something that satisfies a lower-order need. Jobs that pay well and that are performed in safe, clean working conditions with adequate supervision and resources directly or indirectly satisfy these lower-order needs. These “outside the person” factors are extrinsic rewards.

Factors “inside” the person that cause people to perform tasks, intrinsic motivation, arise out of performing a task in and of itself, because it is interesting or “fun” to do. The task is enjoyable, so we continue to do it even in the absence of extrinsic rewards. That is, we are motivated by intrinsic rewards, rewards that we more or less give ourselves. Intrinsic rewards satisfy higher-order needs like relatedness and growth in ERG theory. When we sense that we are valuable contributors, are achieving something important, or are getting better at some skill, we like this feeling and strive to maintain it.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPEN STAX. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Alderfer, C. P. (1972). Existence, relatedness, and growth: Human needs in organizational settings. Free Press.

Atkinson, J. W., & McClelland, D. C. (1948). The projective expression of needs. II. The effect of different intensities of the hunger drive on Thematic Apperception. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38(6), 643-658. doi.org/10.1037/h0061442

DeCharms, R. C. (1957). Affiliation motivation and productivity in small groups. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 55(2), 222-276. www.doi.org/10.1037/h0042577

Dunham, R. B., Pierce, J. L., & Newstrom, J. W. (1983). Job context and job content: A conceptual perspective. Journal of Management, 9(2), 187-202. doi.org/10.1177/014920638300900209

Hall, D. T., & Nougaim, K. E. (1968). An examination of Maslow's need hierarchy in an organizational setting. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3(1), 12-35. doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(68)90024-X

Herzberg, F. (1966). Work and the nature of man. World.

Herzberg, F. (1968). One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harvard Business Review, 46, 54-62. hbr.org/2003/01/one-more-time-how-do-you-motivate-employees

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. (1959). The motivation to work. Wiley.

Lawler III, E. E., & Suttle, J. L. (1972). A causal correlational test of the need hierarchy concept. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 7(2), 265-287. doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(72)90018-9

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 50(4), 370-396. doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper & Row.

Maslow, A. H. (1965). Eupsychian management. Irwin.

McClelland., D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Van Nostrand.

McClelland, D. C. (1970). The two faces of power. Journal of International Affairs, 24(1), 29–47. www.jstor.org/stable/24356663

McClelland, D. C. (1975). Power: The inner experience. Irvington.

McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., & Lowell, E. L. (1953). The achievement motive. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

McGregor, D. (1960). The human side of enterprise. McGraw-Hill.

McGregor, D. (1967). The professional manager. McGraw-Hill.

Wahba, M. A., & Bridwell, L. G. (1976). Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 15(2), 212-240. doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6