Table of Contents |

In this lesson, you will learn how infectious disease differs from other types of disease and from other conditions. The general term disease is defined as any condition in which the normal structure and/or functions of the body are damaged or impaired in some way. For example, someone with a severe respiratory infection (a type of disease) may experience damage to their lung tissue and difficulty obtaining enough oxygen to support normal body functions.

Infectious diseases result from the direct effects of some sort of pathogen. In contrast, there are many diseases and other conditions that are not infectious diseases. The table below describes types of noninfectious diseases and their definitions. Other conditions that affect the ability to function include physical injuries and disabilities, which are not considered diseases.

| Types of Noninfectious Diseases | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Definition | Example |

| Inherited | A genetic disease that is passed to a child from one or both parents | Sickle cell anemia |

| Congenital | Disease that is present at or before birth | Down syndrome |

| Degenerative | Progressive, irreversible loss of function | Parkinson's disease (affecting central nervous system) |

| Nutritional deficiency | Impaired body function due to lack of nutrients | Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency) |

| Endocrine | Disease involving malfunction of glands that release hormones to regulate body functions | Hypothyroidism (thyroid does not produce enough thyroid hormone, which is important for metabolism) |

| Neoplastic | Abnormal growth (benign or malignant) | Cancer |

| Idiopathic | Disease for which the cause is unknown | Idiopathic juxtafoveal retinal telangiectasia (dilated, twisted blood vessels in the retina of the eye) |

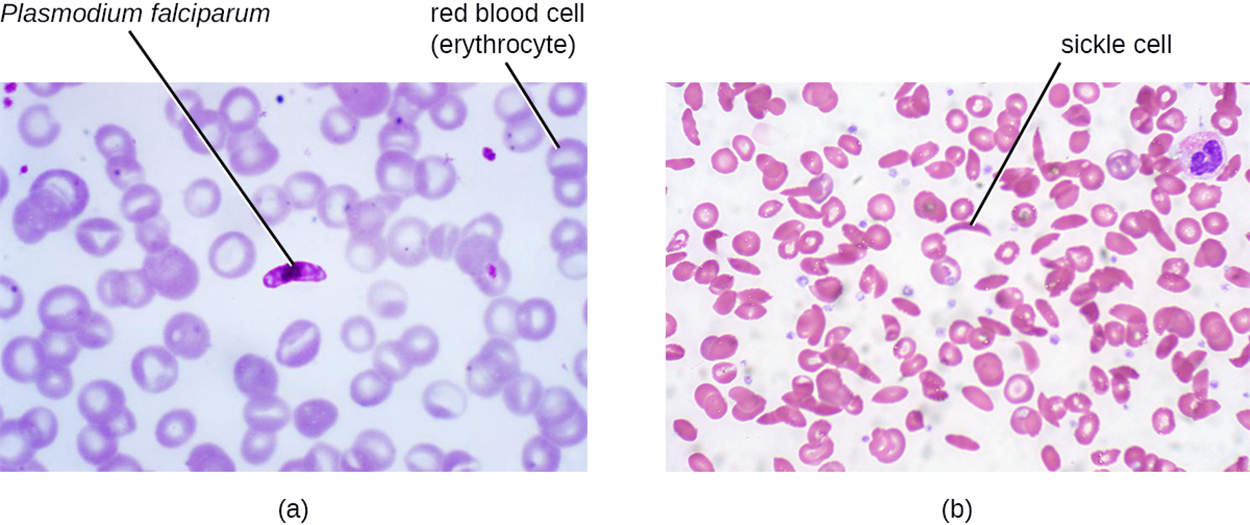

The image below shows examples of infectious versus noninfectious disease in blood smears. In part (a), there is a highlighted protist (Plasmodium falciparum) surrounded by red blood cells (erythrocytes). P. falciparum is one of the pathogens that causes an important infectious disease, malaria. In part (b), there is a blood smear showing red blood cells with no evidence of protists. However, some of the cells have a sickle (crescent) shape. This type of cell is characteristic of the noninfectious disease sickle cell anemia, which is an inherited genetic disorder.

When a patient presents to a medical professional (i.e., shows up for evaluation) asking questions about whether they are sick and in need of treatment, the medical professional needs to consider whichever of these possible causes may be responsible. Sometimes infectious and noninfectious diseases or other conditions can appear similar. However, this course will primarily focus on infectious diseases and how they are caused by microbes with an important exception: in the lesson on the immune system, you will learn how an inappropriate immune response can cause disease.

To study disease, it is often helpful to learn basic word parts that are commonly used in medical terms. These word parts often have a Latin or Greek origin. The table below gives definitions and examples of some common word parts. You may have heard some of these word parts before.

EXAMPLE

Arthritis contains the word parts “arthr/o” (joint) and “itis” (inflammation). Arthritis refers to inflammation of a joint.| Nomenclature of Symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|

| Affix | Meaning | Example |

| cyto- | cell | cytopenia: reduction in the number of blood cells |

| hepat- | of the liver | hepatitis: inflammation of the liver |

| -pathy | disease | neuropathy: a disease affecting nerves |

| -emia | of the blood | bacteremia: presence of bacteria in blood |

| -itis | inflammation | colitis: inflammation of the colon |

| -lysis | destruction | hemolysis: destruction of red blood cells |

| -oma | tumor | lymphoma: cancer of the lymphatic system |

| -osis | diseased or abnormal condition | leukocytosis: abnormally high number of white blood cells |

| -derma | of the skin | keratoderma: a thickening of the skin |

An infection is the successful colonization of a host by a microorganism. Infections can cause disease and this may cause the host to experience changes related to the infection. These changes are grouped into two categories: signs and symptoms.

The signs of a disease are objective and measurable, meaning that they can be observed by a clinician. For example, medical visits often begin with a health care professional taking vital signs to note any changes that may be signs of disease. Vital signs include body temperature, heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure. If someone has an unusually high body temperature (i.e., a fever), then that is a sign of disease. Other changes in vital signs can also signify the presence of an infection. Other examples of signs include measurements from blood analysis (e.g., white blood cell counts).

The symptoms of a disease are subjective. They are experienced by the individual who is sick and can be described but cannot be directly, objectively measured by a clinician even though the clinician can attempt to assess them (e.g., by asking a patient to rate their level of pain on a pain scale). Examples of symptoms include nausea, loss of appetite, and pain. It is important to consider symptoms when diagnosing disease. However, sometimes significant symptoms may be present without objective signs of disease, but symptoms can be more difficult to assess. For example, different people may rank pain differently on a pain scale.

A specific group of signs and symptoms characteristic of a particular disease is called a syndrome. Syndromes are often named using a nomenclature based on signs and symptoms using the word parts in the table above. However, some signs and symptoms are characteristic of multiple conditions and it is not always easy to identify the underlying cause of relatively nonspecific patient concerns such as abdominal pain. Many types of infections cause fevers. Therefore, doctors need to combine information on signs and symptoms with the patient's responses to questions about medical history, recent activities, and potential recent exposures (such as contact with an individual who has a particular condition) to determine appropriate tests and follow-up.

In some cases, diseases are asymptomatic (meaning that they do not produce noticeable signs or symptoms) or subclinical (meaning that any signs and symptoms are relatively mild and therefore relatively difficult to observe and diagnose). People with asymptomatic or subclinical infections may not realize that they are sick.

Diseases can be classified in a variety of ways. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is used in clinical fields to classify diseases and ICD codes are used to designate specific conditions for purposes such as record-taking and billing.

Infectious diseases can be classified into three categories based on the way they spread. Communicable diseases can spread from one person to another by direct or indirect mechanisms. Some communicable diseases are also considered contagious diseases, meaning that they can easily spread from one person to another. Noncommunicable diseases, such as tetanus, do not spread from person to person and are acquired in other ways (e.g., through the entry of the pathogen that causes tetanus, Clostridium tetani, into a wound).

Contagious diseases vary in how easily they are transmitted. Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known and each infected individual can easily spread the disease to multiple others. Each time the infected individual speaks or coughs, viral particles are expelled into the air that can infect others. In contrast, gonorrhea is less contagious because it requires close intimate contact (such as sexual contact) to spread the pathogen.

When diseases are contracted as the result of a medical procedure, they are termed iatrogenic diseases. This can occur when a person undergoes a procedure and a pathogen is somehow introduced into a wound or surgical site. This can also result from catheterization.

Nosocomial diseases (also called health-care-acquired infections, hospital-acquired infections, or HAIs) are diseases acquired in hospitals. These can be highly problematic. People go to hospitals when they are sick, meaning that many pathogens are present and strict protocols (such as frequent handwashing and cleaning of surfaces) are needed to reduce the risk of spread. Secondly, many hospital patients have weakened immune systems that increase their risk of contracting an infection. Finally, although antibiotics are an important treatment tool in hospitals, their use increases the risk that antibiotic-resistant bacteria will be present. Unfortunately, resistant pathogens are common in hospital settings for this reason.

Finally, infections that can be spread from animals to humans are called zoonotic diseases or zoonoses. The term can be restricted to vertebrate animals, but is sometimes used more broadly.

EXAMPLE

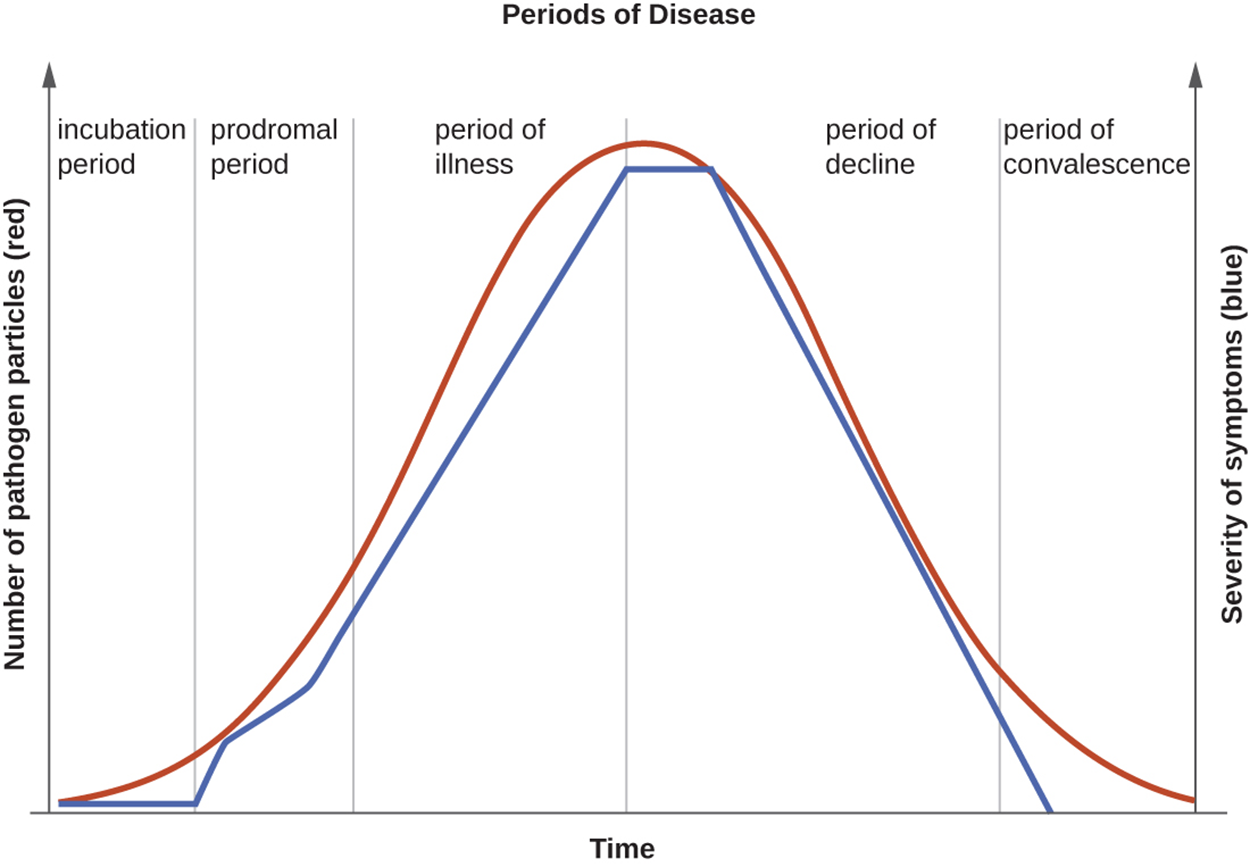

A well-known zoonotic disease is rabies, which is caused by the rabies virus and spread through animal bites or contact with infected saliva.When someone is exposed to a pathogen that causes infectious disease, it begins a series of five periods of disease (also called stages or phases of disease). Throughout these phases, the number of pathogen particles increases at first. As long as the patient survives, the number of pathogen particles then decreases. The graph below shows how the number of pathogen particles (red) and severity of symptoms (blue) change over time as a particular infection moves through the five periods of disease. The lengths of the periods and details of the pattern vary with the type of infection and differences between acute diseases (which occur over a relatively short time) and chronic diseases (which last for a longer time) will be discussed later in this lesson.

Diseases and pathogens differ in when they are most contagious but can be contagious at any point during the five periods of disease. Knowing when a disease is contagious is important in helping to control its spread. Pathogens that are contagious during the incubation period can be especially difficult to control as people are active while not realizing that they are harboring a pathogen. However, other pathogens (such as some diarrheal diseases) may continue to be shed in feces for a long time and this leads to an extended period of contagiousness.

As discussed earlier in the lesson, diseases can be acute or chronic. They can also be latent, meaning that the causal pathogen goes dormant for extended periods of time with no active replication.

Acute diseases involve pathologic changes during a relatively short time (usually ranging from hours to a few weeks). The onset of the disease is relatively rapid and the disease is not long lasting.

EXAMPLE

The period of decline for influenza begins after approximately 1 week.Chronic diseases involve the appearance of pathologic changes over longer time spans ranging from months to a lifespan. The pathogen continues to reproduce over this time.

EXAMPLE

Helicobacter pylori bacteria can live in the stomach and cause recurring infections potentially associated with complications such as ulcers and stomach cancer (Ho et al., 2022). Hepatitis B virus can cause a chronic liver infection.In contrast with chronic diseases, latent diseases occur when pathogens have periods of dormancy.

EXAMPLE

Chickenpox (caused by varicella-zoster virus), herpes (caused by herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2), and mononucleosis (caused by Epstein–Barr virus) enter a latent form but can reactivate to become active infections during times of stress and immunosuppression. Varicella-zoster virus can cause chickenpox in childhood and then reactivate in adulthood to cause shingles. Epstein–Barr virus can go into latency in B cells of the immune system and possibly epithelial cells, then reactivate later to cause B-cell lymphoma.Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY.” ACCESS FOR FREE AT openstax.org/details/books/microbiology. LICENSE: CC ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Ho, J. J. C., Argueta, E. A., & Moss, S. F. (2022). Helicobacter pylori treatment regimens: A US perspective. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 18(6), 313–319. europepmc.org/article/med/36398140