Table of Contents |

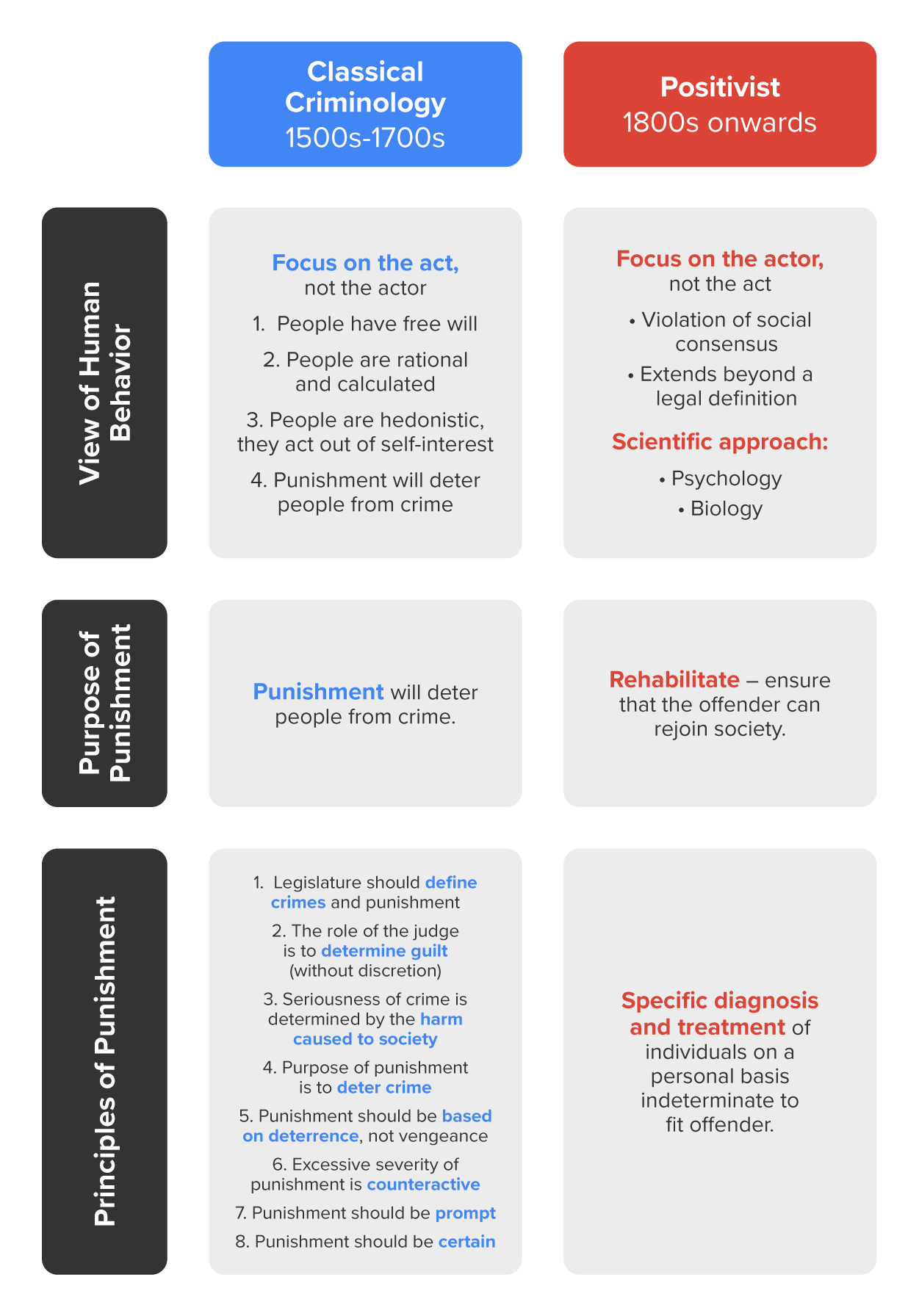

During the Middle Ages, people began to question the justification for how they were being ruled by their governments (Fedorek, 2019). In the mid 17th century, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), a British philosopher, wrote in his seminal piece Leviathan (1651) that people were rational and entitled to such things as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as well as the right to self-government. In the case of punishment, judges were not bound by another’s sentencing prescription simply because there was precedence to do so (Hobbes, 1965). In other words, judges did not have to make the same rulings as their peers on the same types of cases. This type of social contract thinking would later be a building block for the modern criminal justice system. Social contract thinkers believed that people would be willing to invest in laws if they felt those laws were created by the government to protect them (Fedorek, 2019). Social contract thinkers would also be willing to give up some of their self-interests if everyone else did the same.

During the Middle Ages, people began to question the justification for how they were being ruled by their governments (Fedorek, 2019). In the mid 17th century, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), a British philosopher, wrote in his seminal piece Leviathan (1651) that people were rational and entitled to such things as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as well as the right to self-government. In the case of punishment, judges were not bound by another’s sentencing prescription simply because there was precedence to do so (Hobbes, 1965). In other words, judges did not have to make the same rulings as their peers on the same types of cases. This type of social contract thinking would later be a building block for the modern criminal justice system. Social contract thinkers believed that people would be willing to invest in laws if they felt those laws were created by the government to protect them (Fedorek, 2019). Social contract thinkers would also be willing to give up some of their self-interests if everyone else did the same.

Building on the theories of Hobbes and other social contract thinkers at the time, there was an assumption that humans have free will. We can choose one action over another based on perceived benefits and possible consequences. Moreover, human beings are hedonistic. Hedonism is the assumption that people will seek maximum pleasure and avoid pain. Consequently, if we apply the assumptions made in classical criminological theory, we can hold people responsible for their actions because those actions were a choice. These assumptions have been the basis for the United States’ criminal justice system since its inception. Although various theories may have changed the landscape of understanding criminal behavior and the philosophies of punishment over time, the criminal justice system has maintained the assumption that crime is a choice (Fedorek, 2019).

Cesare Beccaria (1738–1794), an Italian philosopher, economist, and politician, is considered the “Father of Criminology.” He authored a book, An Essay on Crimes and Punishment, in 1764, which laid the foundation for what came to be called "the classical school of criminological theory"—and that crime is a free-willed, rational choice. Beccaria also developed the concept of proportionality, which states that for a punishment to be effective, it must fit the crime that it is intended to deter (di Beccaria & Voltaire, 1872).

Furthermore, Beccaria was disgusted with how the courts treated the accused. He wanted the courts to apply a more fair and equal treatment to the convicted instead of the cruel and harsh sentencing practices of the time. Thus, his concept of proportionality was created so that the punishment would be more appropriate for the crime committed. Judges held a lot of power during the time of Beccaria, and many laws were made based on the decisions of those judges. Beccaria sought to change all of that (Fedorek, 2019), claiming the sole purpose of the law was to deter people from committing crimes. These ideas may seem like common sense today, but they were considered radical at the time. Beccaria’s works would later influence many future criminologists in their development of theories such as deterrence theory and rational choice theory.

The positivist school of criminological theory was in direct conflict with the classical school. While the classicists believed that criminal behavior could be explained through rationality of choice and a cost/benefit analysis, positivists believed that criminal behavior was a product of scientifically explained phenomenon. It was not a matter of choice, but a matter of observable, empirical fact that criminality could be identified. There was no better way to prove it than with science. Positivists can be split up into main categories of beliefs: biological positivists and psychological positivists.

The biological positivists were not criminologists in the general definition of the word. At that time, the only recognized science was medical, or biological, science; all other science was considered pseudoscience—statements or beliefs not based on scientific facts—or “fake science.” So, the medical/biological scientists went out to prove that they knew better how to answer the questions about criminal causation than the so-called “social scientists.” Biological positivists believed that some people were born criminals while others were not, and medical/biological science was going to be the tool that could prove it.

The first scientist to give the biological positivists their argument for how criminal behavior was caused was none other than Charles Darwin (1809–1882). Darwin, a British naturalist who is considered the founder of evolutionary science, wrote On the Origin of Species (1859), where he observed what he later conceptualized as natural selection—survival of the fittest. A few years later, he applied his observations to humans in Descent of Man (1871), where he exclaimed that some humans may be an evolutionary throwback to a primitive version of modern mankind. Darwin never wrote about human criminal behavior causation specifically, but his works on species evolution did have a major influence on the biological positivists to come (Fedorek, 2019).

Perhaps the most influential biological positivist was Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), an Italian phrenologist, physician, and the founder of the Italian school of criminology. What made Lombroso so influential was his use of the scientific method in his research experimentation, which helped to legitimize criminology in the minds of medical experts as a valid field of scientific study.  However, how he went about his experiments left much to be desired. Lombroso published The Criminal Man (1876) five years after Darwin drafted his book on evolution, claiming that a third of criminals were born that way because they were atavistic, or evolutionary throwbacks (Fedorek, 2019). He even attempted to prove his theory by developing experiments which measured criminality by physical trait variables: the slope of the forehead, the position of the eyes, the size of the ears, the drop of the mouth, and the color of skin. Widely condemned by experts, Lombroso would later reject his own theoretical rhetoric as he got older, realizing the discriminatory practices of his work. However, the groundwork he laid in legitimizing the field of study was immeasurable, because now criminological research follows the same procedural process that was developed by Lombroso’s experimentations.

However, how he went about his experiments left much to be desired. Lombroso published The Criminal Man (1876) five years after Darwin drafted his book on evolution, claiming that a third of criminals were born that way because they were atavistic, or evolutionary throwbacks (Fedorek, 2019). He even attempted to prove his theory by developing experiments which measured criminality by physical trait variables: the slope of the forehead, the position of the eyes, the size of the ears, the drop of the mouth, and the color of skin. Widely condemned by experts, Lombroso would later reject his own theoretical rhetoric as he got older, realizing the discriminatory practices of his work. However, the groundwork he laid in legitimizing the field of study was immeasurable, because now criminological research follows the same procedural process that was developed by Lombroso’s experimentations.

A few decades after Lombroso’s theory, Charles Goring took Lombroso’s ideas about physical differences and added mental deficiencies. In his book The English Convict (1913), Goring argued that physical abnormalities were also evidence of mental degradations and subject to scientific experimentation for proof (Goring, 1913). The focus on mental qualities led to a new kind of biological positivism—the Intelligence Era.

Moreover, Alfred Binet, the inventor of the IQ test, advocated for the idea of intelligence as a fluid structure. His argument was that human intelligence was not static and that we could gain and lose intelligence as we got older and more experienced. Binet wanted to evaluate school-aged youths to determine who was intellectually competent and who was not. Unfortunately, H. H. Goddard, an American psychologist, disagreed and believed that intelligence was fixed and could not change. Goddard performed IQ tests on students and used the results to categorize them based on their perceived “intelligence.” Subsequently, those who underperformed were institutionalized, deported, or sterilized (Fedorek, 2019). Goddard’s work on intellectual sterilization would lead to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Buck v. Bell (1927), which allowed a Virginia state law for the sexual sterilization of inmates in institutions to promote the health and safety of the patient and the welfare of society to continue (Buck v. Bell 274 US 200 [1927], 2023).

Moreover, Alfred Binet, the inventor of the IQ test, advocated for the idea of intelligence as a fluid structure. His argument was that human intelligence was not static and that we could gain and lose intelligence as we got older and more experienced. Binet wanted to evaluate school-aged youths to determine who was intellectually competent and who was not. Unfortunately, H. H. Goddard, an American psychologist, disagreed and believed that intelligence was fixed and could not change. Goddard performed IQ tests on students and used the results to categorize them based on their perceived “intelligence.” Subsequently, those who underperformed were institutionalized, deported, or sterilized (Fedorek, 2019). Goddard’s work on intellectual sterilization would lead to the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Buck v. Bell (1927), which allowed a Virginia state law for the sexual sterilization of inmates in institutions to promote the health and safety of the patient and the welfare of society to continue (Buck v. Bell 274 US 200 [1927], 2023).

Best known for his work in the psychological field of personality disorders, Austrian neurologist and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) postulated that the human mind was separated into three distinct psychoanalytical types: the id, the ego, and the superego. Through his studies, Freud theorized that criminal behavior was a product of mental illness, motivated by unconscious psychosexual conflict (Fitzpatrick, 1976).

Best known for his work in the psychological field of personality disorders, Austrian neurologist and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) postulated that the human mind was separated into three distinct psychoanalytical types: the id, the ego, and the superego. Through his studies, Freud theorized that criminal behavior was a product of mental illness, motivated by unconscious psychosexual conflict (Fitzpatrick, 1976).

Then, there were those who wanted to study personality traits of criminals. Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck (1950), Polish American criminologists, determined that there was no such thing as a criminal personality, but that there were some personality traits that were clustered together. Their work included a longitudinal study—a type of experiment that takes a long time to complete—of 1,000 teenage juvenile delinquent and non-delinquent boys to try and understand the causes of criminal behavior in youths. Their findings resulted in no explanations as to the causation of delinquent behavior; however, there were correlations between certain personality types and criminal behavior: low self-control, low empathy, and an inability to learn from punishment (Fedorek, 2019). These traits cause crime in interaction with the social environment, but having personality traits linked to criminal behavior does not necessarily mean that one will become a criminal. That is, biology and psychology play a role in how we interact with our environment and react to the laws that try to regulate behavior. Our environment, in turn, also influences our behavior, both psychologically and biologically.

Then, there were those who wanted to study personality traits of criminals. Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck (1950), Polish American criminologists, determined that there was no such thing as a criminal personality, but that there were some personality traits that were clustered together. Their work included a longitudinal study—a type of experiment that takes a long time to complete—of 1,000 teenage juvenile delinquent and non-delinquent boys to try and understand the causes of criminal behavior in youths. Their findings resulted in no explanations as to the causation of delinquent behavior; however, there were correlations between certain personality types and criminal behavior: low self-control, low empathy, and an inability to learn from punishment (Fedorek, 2019). These traits cause crime in interaction with the social environment, but having personality traits linked to criminal behavior does not necessarily mean that one will become a criminal. That is, biology and psychology play a role in how we interact with our environment and react to the laws that try to regulate behavior. Our environment, in turn, also influences our behavior, both psychologically and biologically.

Source: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network'S “CCRJ 1013: Introduction to Criminal Justice”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT LOUIS. LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.

REFERENCES

Buck v. Bell 274 US 200 (1927). (2023, February 25). Retrieved from Oyez.org: www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/274us200

di Beccaria, C. B., & Voltaire. (1872). An Essay on Crimes and Punishments. By the Marquis Beccaria of Milan. With a Commentary by M. de Voltaire. A New Edition Corrected. Albany: W.C. Little & Co.

Fedorek, B. (2019). Criminological Theory. In A. S. Burke, D. Carter, B. Fedorek, T. Morey, L. Rutz-Burri, & S. Sanchez, SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System. (pp. 157-187). Open Oregon Educational Resources.

Fitzpatrick, J. (1976). Psychoanalysis and Crime: A Critical Survey of Salient Trends in the Literature. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 423, 67-74. www.jstor.org/stable/1041423

Goring, C. (1913). The English Convict. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Hobbes, T. (1965). Leviathan with an Essay written by the late W.G. Pogson Smith. Oxford: Oxford University Press.