Table of Contents |

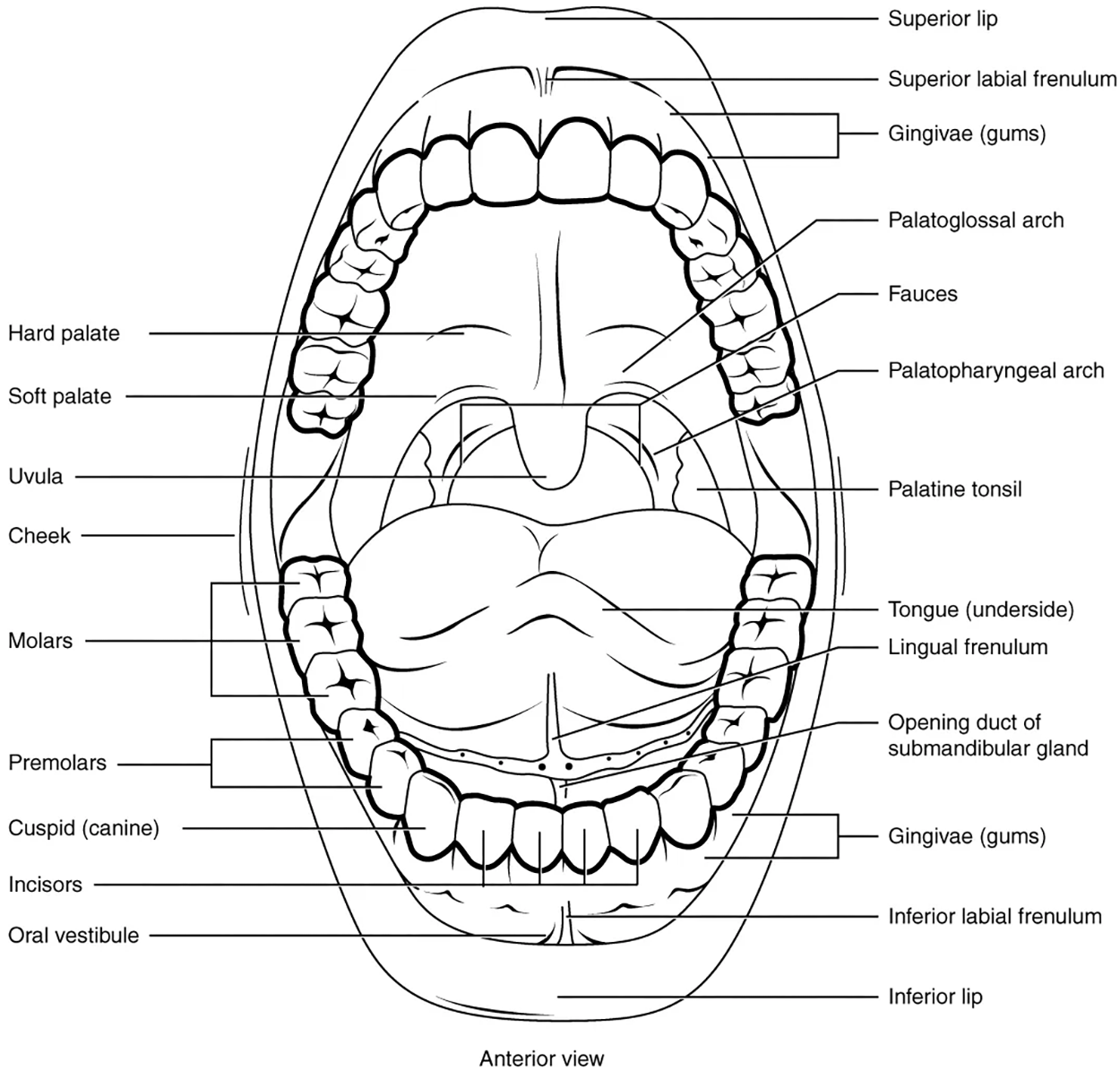

The cheeks, tongue, and palate frame the mouth, which is also called the oral cavity (or buccal cavity).

At the entrance to the mouth are the lips, or labia (singular = labium). Their outer covering is skin, which transitions to a mucous membrane inside the mouth.

The lips cover the orbicularis oris muscle, which regulates what comes in and goes out of the mouth. The labial frenulum is a midline fold of mucous membrane that attaches the inner surface of each lip to the gum. The cheeks make up the oral cavity’s sidewalls. While their outer covering is skin, their inner covering is mucous membrane. This membrane is made up of non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium. Between the skin and mucous membranes are connective tissue and buccinator muscles.

The pocket-like part of the mouth that is framed on the inside by the gums and teeth, and on the outside by the cheeks and lips, is called the oral vestibule. Moving farther into the mouth, the opening between the oral cavity and throat (oropharynx) is called the fauces (like the kitchen "faucet"). The main open area of the mouth, or oral cavity proper, runs from the gums and teeth to the fauces.

When you are chewing, you probably do not find it difficult to breathe simultaneously. The next time you have food in your mouth, notice how the arched shape of the roof of your mouth allows you to handle both digestion and respiration at the same time. This arch is called the palate. The anterior (front) region of the palate serves as a wall (or septum) between the oral and nasal cavities as well as a rigid shelf against which the tongue can push food. It is created by the maxillary and palatine bones of the skull and, given its bony structure, is known as the hard palate.

If you run your tongue along the roof of your mouth, you’ll notice that the hard palate ends in the posterior oral cavity, and the tissue becomes fleshier. This part of the palate, known as the soft palate, is composed mainly of skeletal muscle. You can therefore manipulate, subconsciously, the soft palate—for instance, to yawn, swallow, or sing.

A fleshy bead of tissue called the uvula drops down from the center of the posterior (back) edge of the soft palate. Although some have suggested that the uvula is a vestigial organ (an unused organ that does not currently have function), it serves an important purpose. When you swallow, the soft palate and uvula move upward, helping to keep foods and liquid from entering the nasal cavity. Unfortunately, it can also contribute to the sound produced by snoring. Two muscular folds extend downward from the soft palate, on either side of the uvula. Toward the front, the palatoglossal arch lies next to the base of the tongue; behind it, the palatopharyngeal arch forms the superior and lateral margins of the fauces.

Between these two arches are the palatine tonsils, which are clusters of lymphoid tissue that protect the pharynx. The lingual tonsils are located at the base of the tongue.

The digestive functions of the mouth are summarized in the table below, and you will learn more about some of these structures throughout the rest of this lesson.

| Digestive Functions of the Mouth | ||

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Action | Outcome |

| Lips and cheeks | Confine food between teeth |

|

| Salivary glands | Secrete saliva |

|

| Tongue’s extrinsic muscles | Move tongue sideways, and in and out |

|

| Tongue’s intrinsic muscles | Change tongue shape |

|

| Taste buds | Sense food in mouth and sense taste |

|

| Lingual glands | Secrete lingual lipase |

|

| Teeth | Shred and crush food |

|

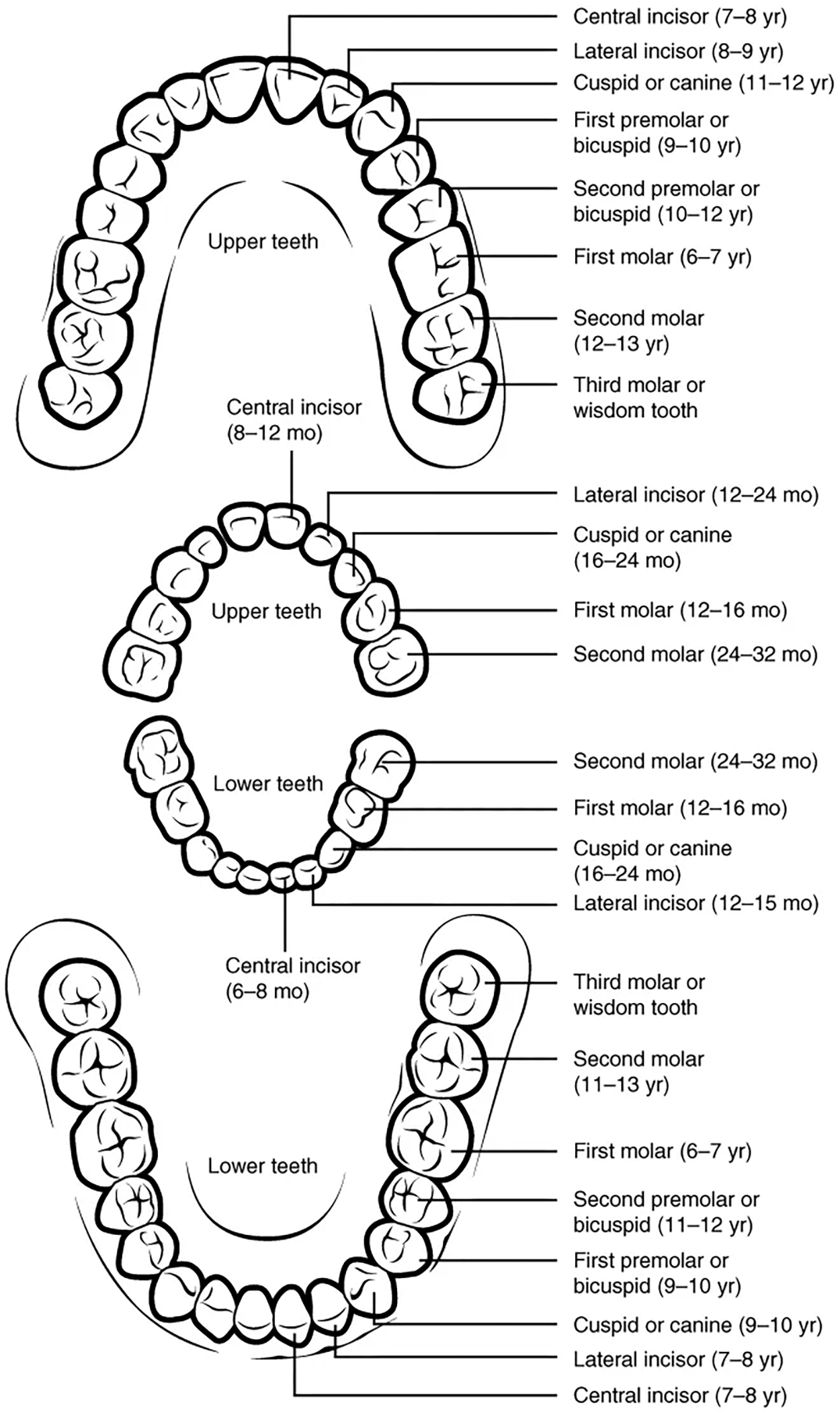

The teeth, or dentes (singular = dens), are organs similar to bones that you use to tear, grind, and otherwise mechanically break down food.

During the course of your lifetime, you have two sets of teeth (one set of teeth is a dentition). Your 20 deciduous teeth, or baby teeth, first begin to appear at about 6 months of age. Between approximately age 6 and 12, these teeth are replaced by 32 permanent teeth. Moving from the center of the mouth toward the side, these are as follows:

The teeth are secured in the alveolar processes (sockets) of the maxilla and the mandible.

Gingivae (commonly called the gums) are soft tissues that line the alveolar processes and surround the necks of the teeth. Teeth are also held in their sockets by a connective tissue called the periodontal ligament.

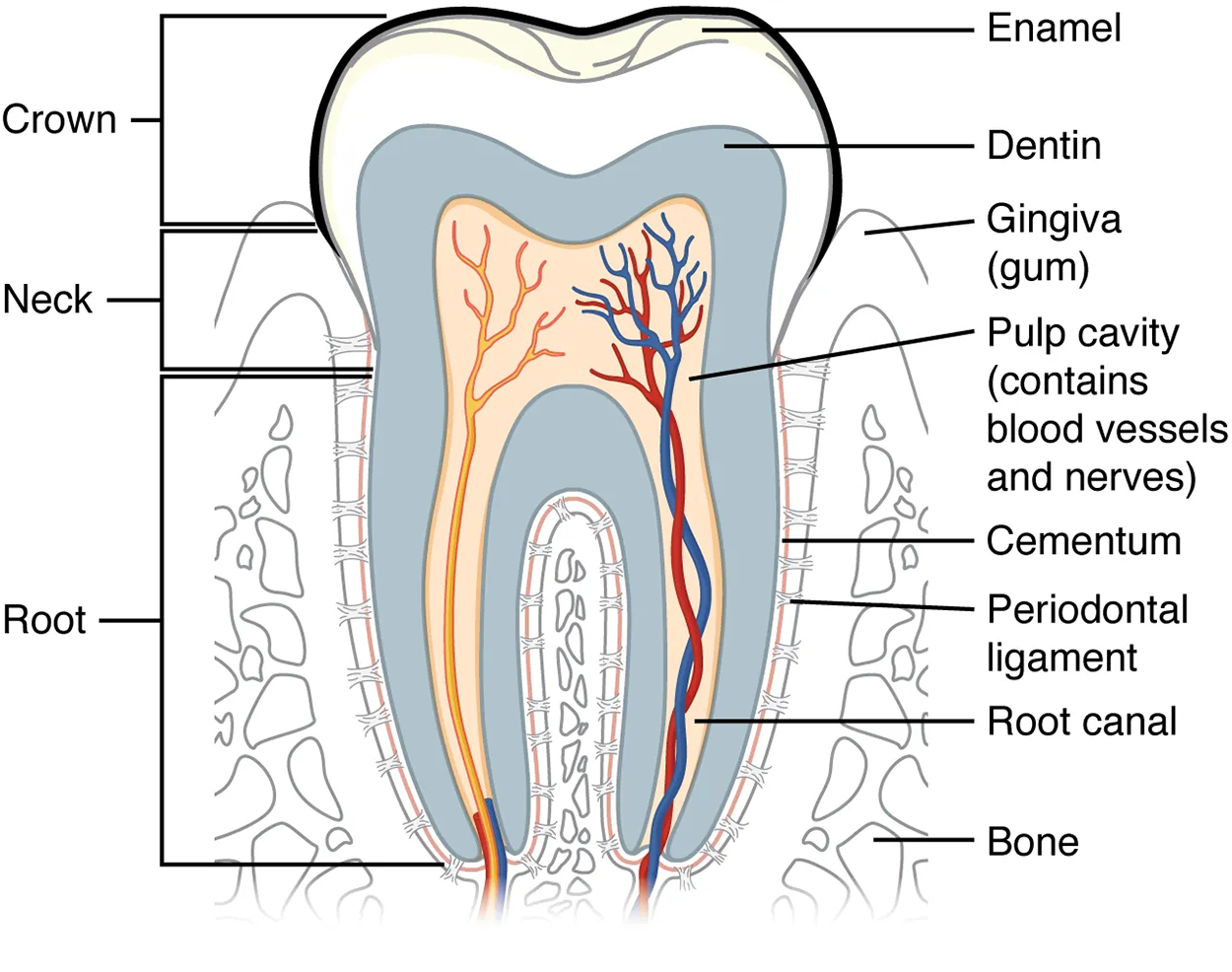

The two main parts of a tooth are the crown, which is the portion projecting above the gum line, and the root, which is embedded within the maxilla and mandible. Both parts contain an inner pulp cavity, containing loose connective tissue through which run nerves and blood vessels. The region of the pulp cavity that runs through the root of the tooth is called the root canal. Surrounding the pulp cavity is dentin, a bone-like tissue. In the root of each tooth, the dentin is covered by an even harder bone-like layer called cementum. In the crown of each tooth, the dentin is covered by an outer layer of enamel, the hardest substance in the body.

IN CONTEXT

Tooth Decay

Although enamel protects the underlying dentin and pulp cavity, it is still nonetheless susceptible to mechanical and chemical erosion, or what is known as tooth decay. The most common form, dental caries (cavities), develop when colonies of bacteria feeding on sugars in the mouth release acids that cause soft tissue inflammation and degradation of the calcium crystals of the enamel.

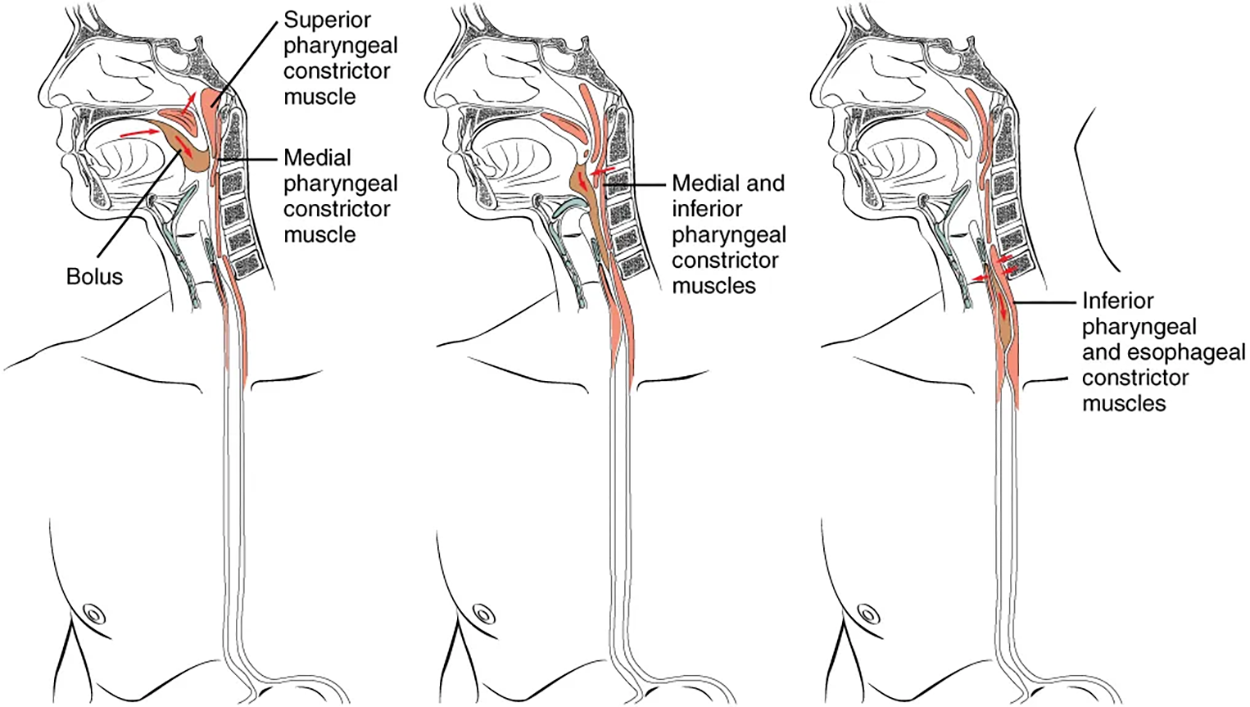

Deglutition is another word for swallowing—the movement of food from the mouth to the stomach. The entire process takes about 4 to 8 seconds for solid or semisolid food, and about 1 second for very soft food and liquids. Although this sounds quick and effortless, deglutition is, in fact, a complex process that involves both the skeletal muscle of the tongue and the muscles of the pharynx and esophagus. It is aided by the presence of mucus and saliva.

There are three stages in deglutition: the voluntary phase, the pharyngeal phase, and the esophageal phase. The autonomic nervous system controls the latter two phases.

The voluntary phase of deglutition (also known as the oral or buccal phase) is so-called because you can control when you swallow food. In this phase, chewing has been completed, and swallowing is set in motion. The tongue moves upward and backward against the palate, pushing the bolus to the back of the oral cavity and into the oropharynx. Other muscles keep the mouth closed and prevent food from falling out. At this point, the two involuntary phases of swallowing begin.

The pharyngeal phase is the first step of swallowing that is irreversible. In this phase, there is rapid muscle contraction that forces the bolus into the esophagus. This occurs by stimulation of receptors in the oropharynx that sends impulses to the deglutition center (a collection of neurons that controls swallowing) in the medulla oblongata. Impulses are then sent back to the uvula and soft palate, causing them to move upward and close off the nasopharynx. The laryngeal muscles also constrict to prevent aspiration of food into the trachea. At this point, deglutition apnea takes place, which means that breathing ceases for a very brief time. Contractions of the pharyngeal constrictor muscles move the bolus through the oropharynx and laryngopharynx. Relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter then allows food to enter the esophagus.

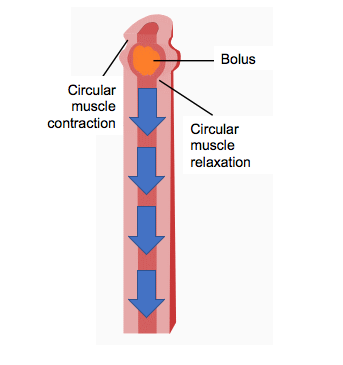

The entry of food into the esophagus marks the beginning of the esophageal phase of deglutition, which is when the bolus moves through the esophagus to the stomach and the initiation of peristalsis. As in the previous phase, the complex neuromuscular actions are controlled by the medulla oblongata. Peristalsis propels the bolus through the esophagus and toward the stomach. The circular muscle layer of the muscularis contracts, pinching the esophageal wall and forcing the bolus forward. At the same time, the longitudinal muscle layer of the muscularis also contracts, shortening this area and pushing out its walls to receive the bolus. In this way, a series of contractions keeps moving food toward the stomach. When the bolus nears the stomach, distention (enlargement) of the esophagus initiates a short reflex relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter that allows the bolus to pass into the stomach. During the esophageal phase, esophageal glands secrete mucus that lubricates the bolus and minimizes friction.

As you're chewing food, your tongue will push the food against your palate, which is also known as the roof of your mouth, and mix it with saliva. Once the mouth is done mechanically and chemically digesting the food, it is then swallowed; the chewed ball of food that is swallowed is called a bolus.

As the food is swallowed, it will move down through your esophagus toward your stomach via peristalsis. As you previously learned, peristalsis is characterized by wave-like contraction of the muscles of the digestive tract that propels food through it. Your esophagus will contract just above the bolus and push it downward. Then, a new contraction will go above it again and push it down farther.

Peristalsis is also how your stomach mechanically breaks the bolus down further and how the intestines push food through your digestive tract.

SOURCE: THIS TUTORIAL HAS BEEN ADAPTED FROM (1) OPENSTAX “ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY 2E”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/ANATOMY-AND-PHYSIOLOGY-2E/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. (2) OPENSTAX “MICROBIOLOGY”. ACCESS FOR FREE AT OPENSTAX.ORG/BOOKS/MICROBIOLOGY/PAGES/1-INTRODUCTION. LICENSING (1 & 2): CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL.